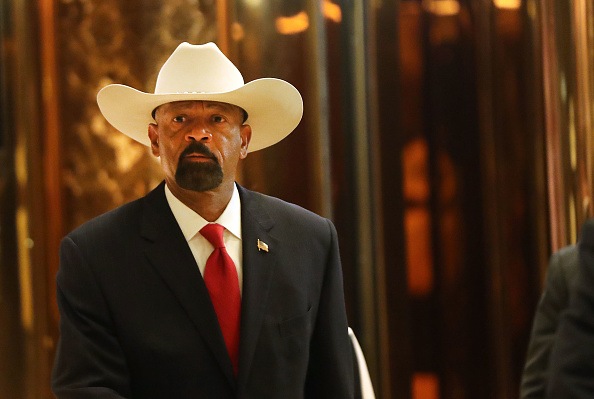

David Clarke, the mustachioed and cowboy-hatted sheriff of Milwaukee County, made a request to the Department of Homeland Security earlier this month.

In a March 9 letter to acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement Thomas Homan, Clarke said he was “deeply concerned” about the potential threats that he said undocumented immigrants pose to citizens under his jurisdiction. He asked ICE to empower his officers to round up undocumented immigrants in his community.

Clarke, a cheerleader of President Donald Trump’s hardline immigration policies, wanted Milwaukee County to join an ICE program called 287(g). Named after a provision in a 1996 immigration law, the voluntary program lets the feds deputize state and local officers to perform some of the duties of federal immigration agents. Clarke wanted to participate in a version of the program that screens for undocumented immigrants in local jails and allows trained officers to patrol the streets and identify undocumented immigrants in the community for removal.

The controversial sheriff is one of several to make such a request in the early weeks of the Trump Administration. Officials in Anne Arundel County, Md., have applied to join the program. Bill Waybourn, the sheriff of Tarrant County, Tex., wants deputies in his jail to be able to identify undocumented immigrants. Sheriff P.J. Tanner of Beaufort County, S.C. applied to revive the “task force model” of 287(g), which would allow certain officers in his jurisdiction to arrest and detain the “worst of the worst” among undocumented immigrants, including gang members, drug dealers and other violent criminals.

Those requests are pending, and formalizing the agreements will take time. But Trump’s support for 287(g) alarms immigration-reform advocates. “I thought that we were close to closing the chapter of the ugly history of the 287(g) program,” says Chris Newman, the legal director of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network. Since the first 287(g) agreements were signed in 2002, the program has been a source of controversy. The Obama Administration reduced its use, instead focusing on a mandatory program that identified criminal undocumented immigrants in police custody. The number of places participating in 287(g) dwindled during Obama’s presidency, from 72 in 2011 to 37 in 16 states as of this month.

That could change under Trump. The President asked DHS to enter into more 287(g) partnerships in his January executive order on immigration. Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly called the program a “highly successful force multiplier” in memos outlining the order’s guidelines. “Empowering state and local law enforcement to assist in the enforcement of federal immigration law is critical to an effective enforcement strategy,” Kelly said. Between 2006 and 2015, more than 402,000 immigrants were identified for removal as a result of the program.

Trump has ordered DHS to hire 15,000 new agents and taken aim at so-called sanctuary cities— places where local officials choose either to limit engagements with ICE or not actively enforce civil immigration law—by threatening to block some federal funding. But hiring officers takes time, and getting the money to pay them takes an act of Congress. To fulfill his pledges, the President could use the help of local and state officials. Through 287(g), ICE can tap into local resources to carry out its mission.

The program has a fraught history. Initially, its focus was supposed to be narrow: officers apprehended only dangerous criminals, and its application was limited to jails. But that changed in 2006, when Jim Pendergraph, a sheriff in the Charlotte, N.C., area, allowed his officers to screen for violations of civil immigration law. Pendergraph, whose goal was to get as many undocumented immigrants out of the area as possible, went on to become the chief of ICE’s Office of State and Local Coordination, and his model informed the department’s approach as the program’s use grew, especially in the South.

Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio ran the most notorious program, using it to justify massive sweeps during which Latinos were racially profiled and suffered civil rights abuses. In Arpaio’s Maricopa County, “there were people in yellow suits running around catching Hispanics,” recalls Muzaffar Chishti of the Migration Policy Institute, which published an in-depth study on the programs in 2011. “ There was a lot of bad imagery.”

Given this history, some law enforcement leaders have come forward to say they won’t participate in the program, no matter Trump’s wishes. “Local law enforcement is pushing back because [287(g)] doesn’t serve their interests in terms of public safety,” says Ali Noorani, the executive director of the National Immigration Forum. In late February, the newly elected sheriff of Texas’s Harris County, which includes Houston, announced he would no longer participate in the program. The Los Angeles Chief of Police said in November he planned to maintain separation between his department’s activities and those of immigration enforcement officials. After a recent raid in Santa Cruz, Calif., the city’s police chief denounced the feds’ tactics.

“We’re not here to enforce federal, civil immigration laws. We don’t enforce federal civil debt collection laws. We’re a criminal law agency,” says Lawrence Byrne of the New York City Police Department. “Our mission is to prevent crime, investigate crime, and prevent acts of terrorism.”

On March 1, the 63 police chiefs and sheriffs who make up the Law Enforcement Immigration Task Force signed onto a letter that said they don’t want their officers acting as immigration enforcement agents. Mike Tupper, the chief of police in Marshalltown, Iowa, was one of the signatories. He says programs like 287(g) make it hard for immigrant communities to trust local officers. If immigrants cannot differentiate between the local police and immigration-enforcement officers, Tupper says, they won’t know who to trust if they witness or are the victim of a crime. “The nuts and bolts of policing is daily interaction with the community that you’re serving,” the chief told TIME. “It’s very difficult to do that when you’re engaged in federal immigration enforcement.”

This view has been criticized by Trump and fellow immigration hardliners. The Federation for American Immigration Reform says that local authorities that shun enforcement responsibilities are being “unfair” to legal immigrants, and “create an environment where terrorists and other criminal aliens can go unnoticed and uninterrupted.”

Like other opponents of the 287(g) program, Harris County, Texas, Sheriff Ed Gonzalez says it is not that he doesn’t want to work with ICE, or even that he will not. He told TIME he backed out of the 287(g) program earlier this year not only because of the controversy it generated, but also because of his department’s limited resources. The county spent $675,000 staffing the program, money Gonzalez says could be used to buy new patrol cars or bolster his investigative unit. “I felt that it would also be appropriate,” Gonzalez says, “to separate ourselves from that program and to focus instead on community policing.”

The 287(g) program is more popular among sheriffs than police chiefs. Newman, of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, says that may be because police chiefs are more pragmatic, while elected sheriffs—like Clarke, a celebrity among the far-right grassroots—can be driven by politics. Of the 37 existing 287(g) agreements, only two are with metropolitan police departments—one in Las Vegas and one in Carrollton, Tex. In the city of Milwaukee, the seat of Clarke’s county, Police Chief Edward Flynn has said he does not intend to have officers act in an immigration-enforcement capacity.

Pro-immigration advocates like Newman says they hope that “racist” policies like the 287(g) program are not on the rise again under Trump. “I think in the future,” he says, “we will look on this period with embarrassment.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Introducing TIME's 2024 Latino Leaders

- How to Make an Argument That’s Actually Persuasive

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- The Ordained Rabbi Who Bought a Porn Company

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

- The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com