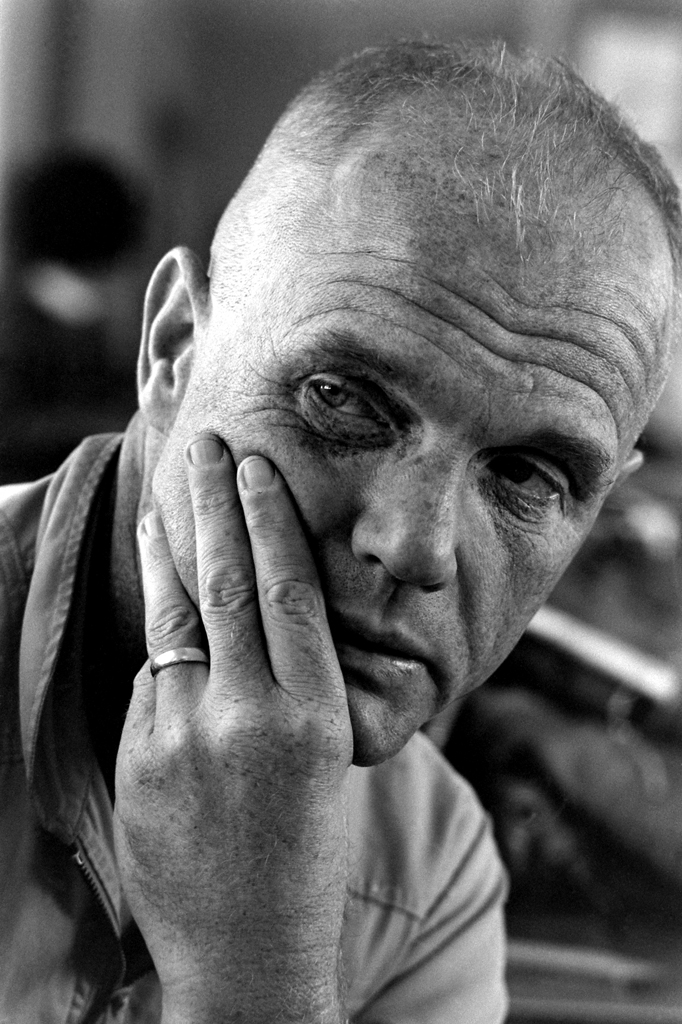

Astronaut John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth and the third in space, died Thursday. A former U.S. Senator from Ohio, he was 95.

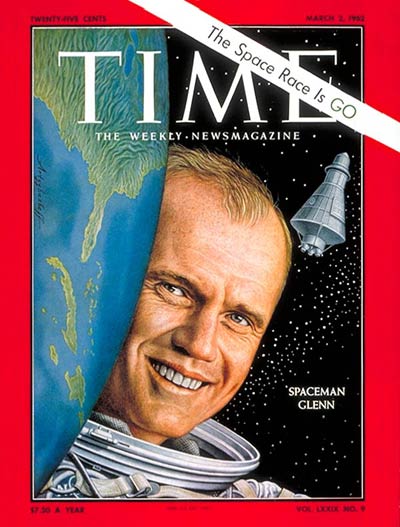

Glenn landed on the cover of the March 2, 1962, issue of TIME after circling the globe three times in 4 hours and 56 minutes—at speeds of more than 17,000 mph—on Feb. 20, 1962.

The achievement came 10 months after Soviet Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space and made one full orbit around Earth (April 12, 1961) and nine months after Alan Shepard became the first American in space (May 5, 1961), followed by Gus Grissom (July 21, 1961). Thus, his mission was a critical step in the American mission to win the Cold War in space by fulfilling President John F. Kennedy, Jr.’s commitment to “achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

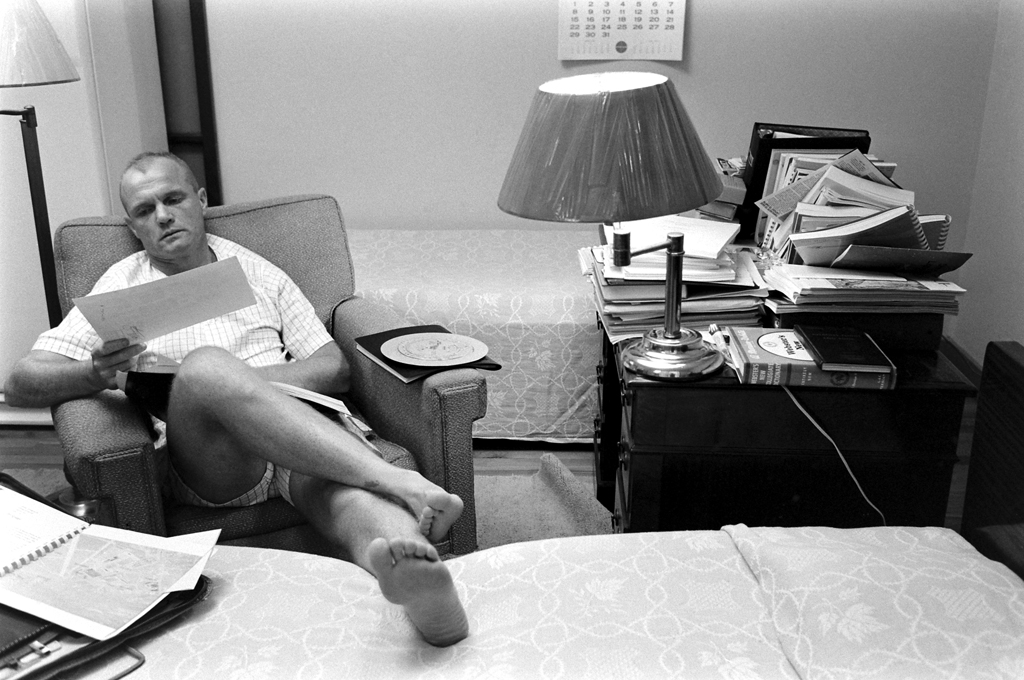

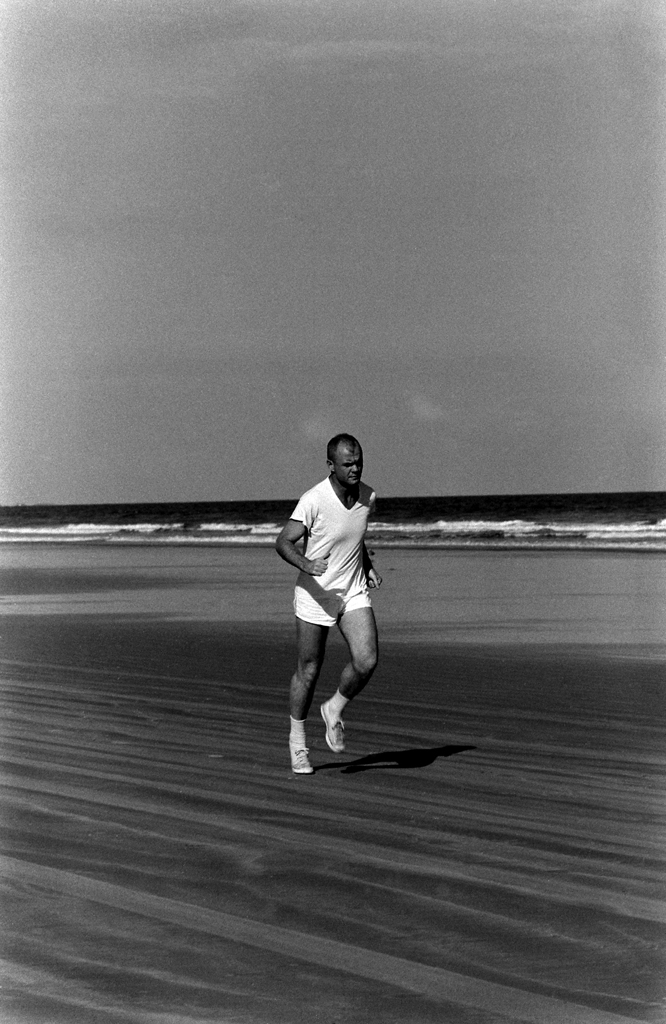

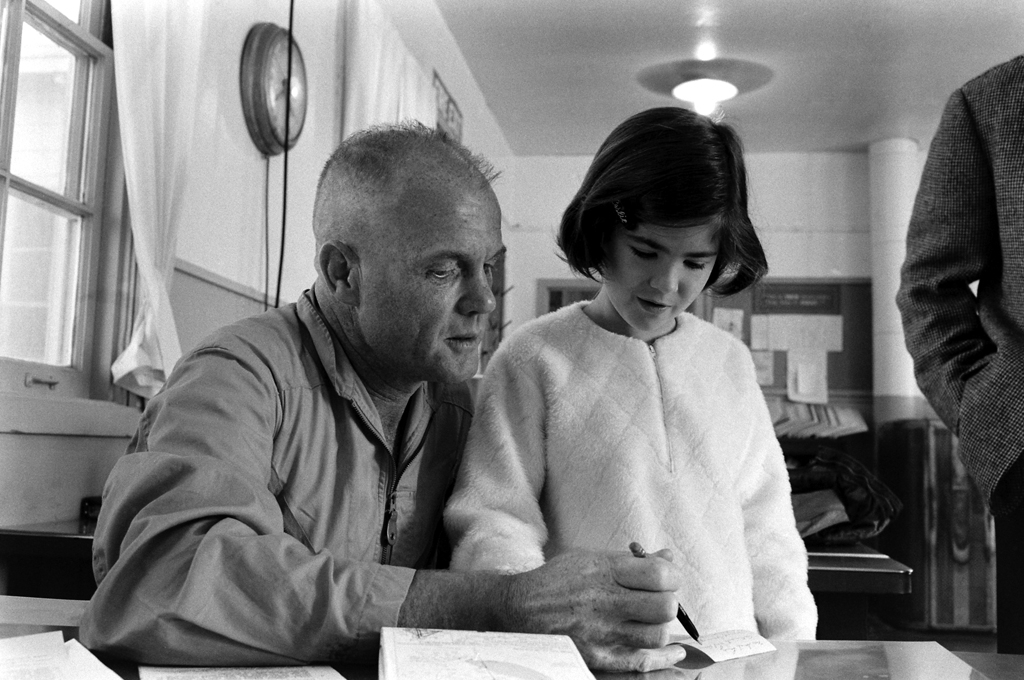

TIME launched its profile of Glenn by pointing out that the grandeur of the undertaking was quite matched by the affect of the man: “In his flight across the heavens, John Glenn was a latter-day Apollo, flashing through the unknown, sending his cool observations and random comments to the earth in radio thunderbolts, acting as though orbiting the earth were his everyday occupation. Back on earth, Glenn seemed to be quite a different fellow—an enormously appealing man, to be sure, but as normal as blueberry pie.”

The Ohio native’s life had indeed started out in complete normalcy: he spent his time playing football and basketball, and reading Buck Rogers. He later joined the Marine Corps, becoming a decorated test pilot and a combat flyer, earning the rank of colonel. (Ted Williams, the legendary Red Sox left fielder who was also a Marine pilot, told TIME, “The man is crazy,” referring to the way he apparently liked to show off his flying skill in dangerous stunts.) But, though his achievements as a pilot were notable, as a career it was still within the range of ordinary.

So how did he get to be an astronaut? TIME explained:

Early in his career, Glenn developed the art of “sniveling.” Explains Marine Lieut. Colonel Richard Rainforth, who flew beside Glenn in both World War II and Korea: “Sniveling, among pilots, means to work yourself into a program, whether it happens to be your job or not. Sniveling is perfectly legitimate, and Johnny is a great hand at it.” In 1957 Glenn sniveled the Marines into letting him try to beat the speed of sound from coast to coast. Flying an F8U, Glenn failed by nine minutes, but he did knock 23 1/2 min. off the coast-to-coast speed record by covering the distance in 3 hr. 23 min. at an average speed of 726 m.p.h.

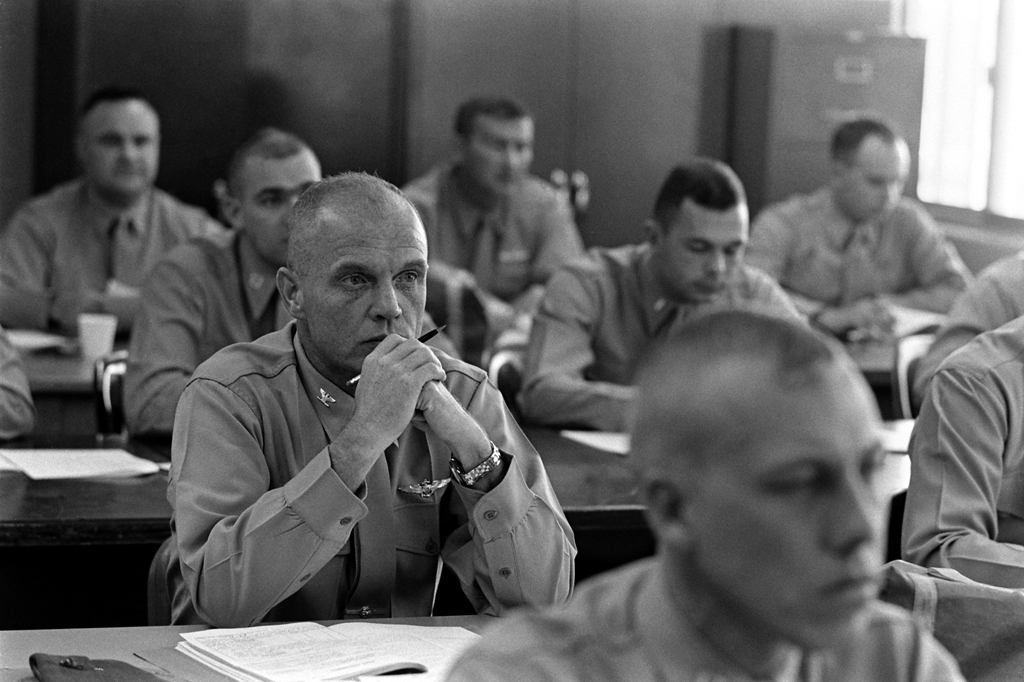

Then, in 1959, Glenn resolutely set out to snivel his way into the toughest program of all: Project Mercury. He started with two handicaps: he lacked a college degree, and, at 37, he was considered to be an old man. But Glenn managed to get permission to go along as an “observer” with one prime candidate of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics. When the candidate failed an early test, recalls Rainforth, “Johnny stepped up, chest high, and offered himself as a candidate. They took him.”

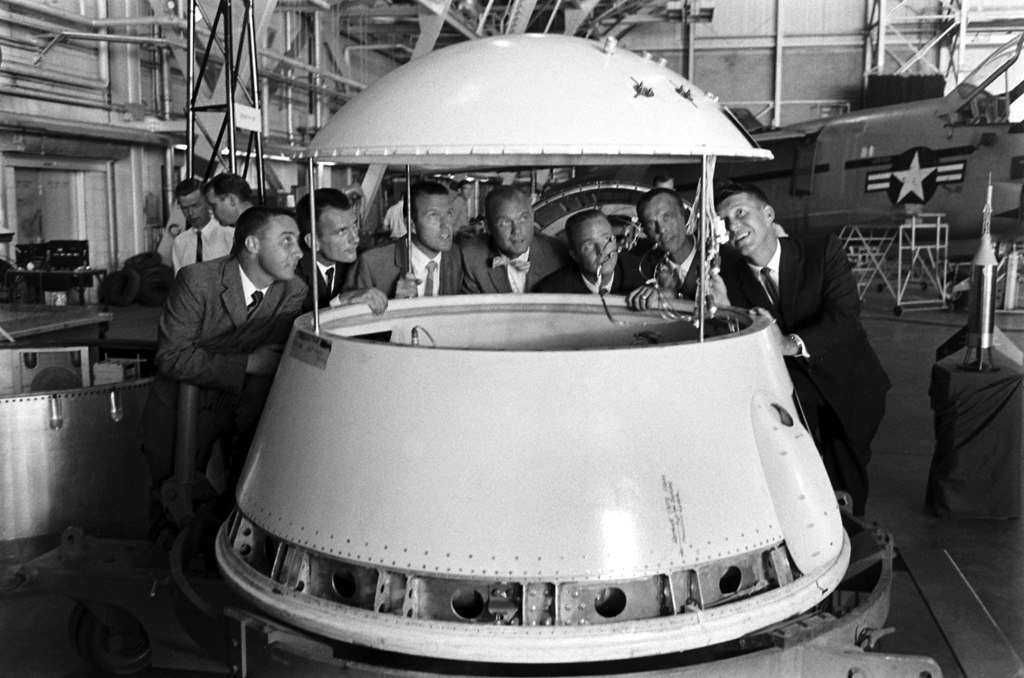

…Candidate Glenn and 510 others were run through a wringer of mental and physical tests. Doctors charted their brain waves, skewered their hands with electrodes to pick up the electrical impulses that would tell how quickly their muscles responded to nerve stimulation. Glenn held up tenaciously under tests of heat and vibration, did especially well with problems of logical reasoning. Says Dr. Stanley White, a Project Mercury physician: “Glenn is a guy who lives by facts.”

To the surprise of no one who ever knew him, Glenn was one of the seven former test pilots who were picked to become the nation’s first astronauts.

In terms of what it felt like to be in space, he reported “no ill effects at all” from zero gravity and described weightlessness as “something you could get addicted to.” It was also “hot” inside the Friendship 7 capsule at times; at one point, the temperature hit 108º in the cabin. He saw four “beautiful” sunsets and said nightfall in space is akin to nightfall in the desert “on a very clear, brilliant night when there’s no moon and the stars just seem to jump out at you.”

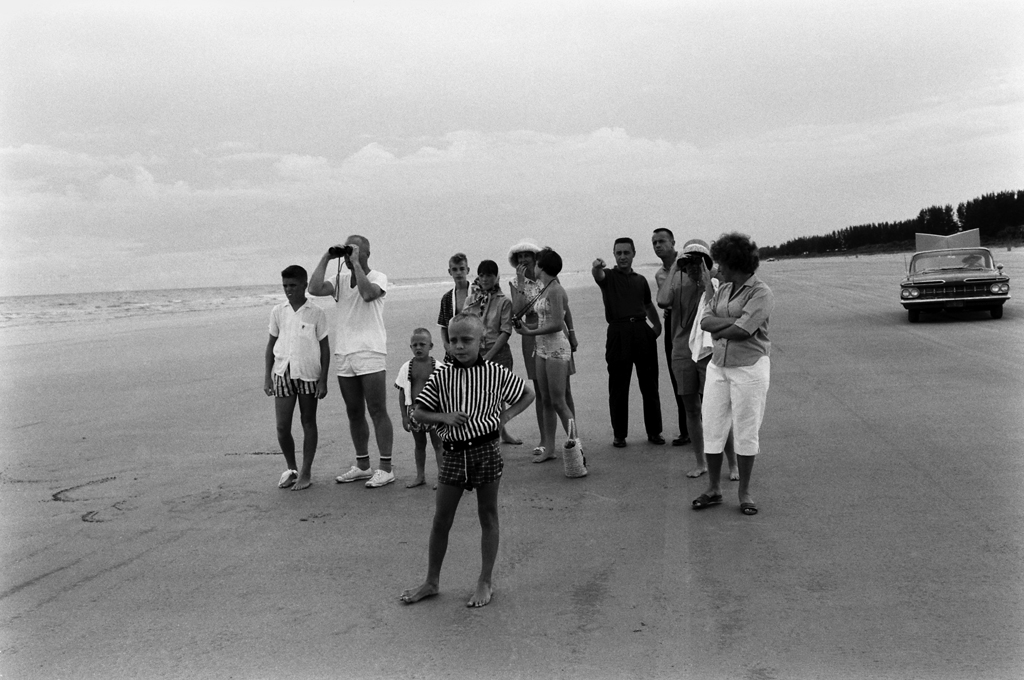

John Glenn: Rare and Classic Photos From an American Life

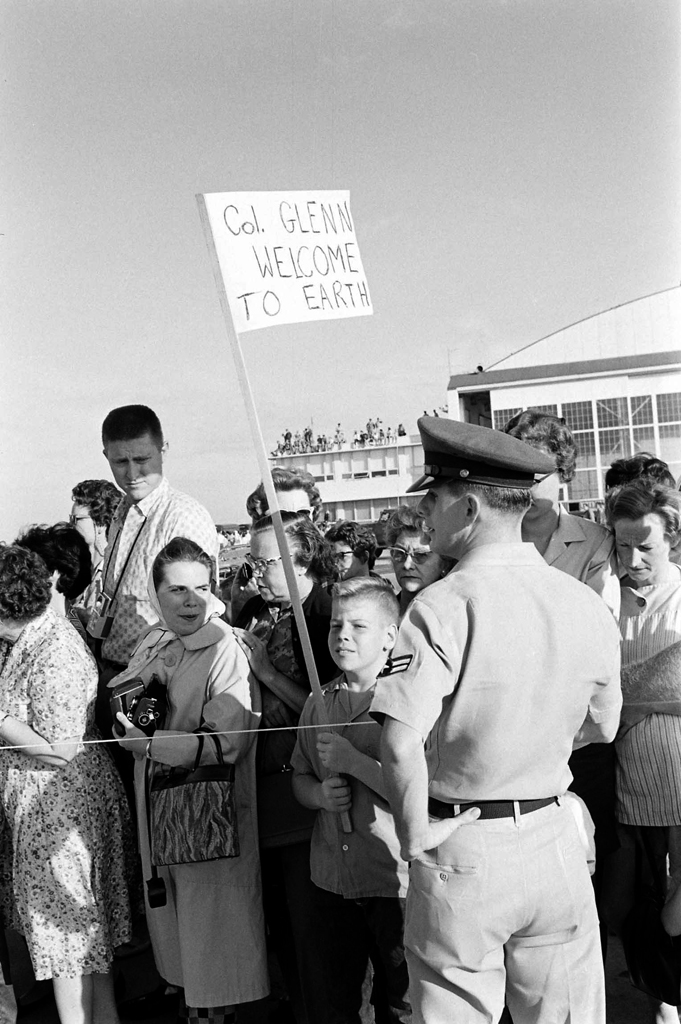

While TIME declared, “Not since Lindy had the U.S. had such a hero”—referring to Charles Lindbergh, who accomplished the first solo nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean—Glenn tried to emphasize at a press conference following his splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean that spaceflight still had a long way to go: “If you think of the enormity of space, it makes our efforts seem puny. But these are all step-by-step functions we go through. The manned flights we’ve had to date have added information. This flight, I hope, added a bit more. And there are more to come.”

Read the full cover story, here in the TIME Vault: Spaceman Glenn

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com