Today, Brown v. Board of Education—with its ruling in favor of equality—is known as the definitive Supreme Court case about the segregation of American schools. But three decades earlier, a Chinese family in the Mississippi Delta region brought their own school-segregation case to the Supreme Court—and not only lost, but set a painful precedent in favor of segregation.

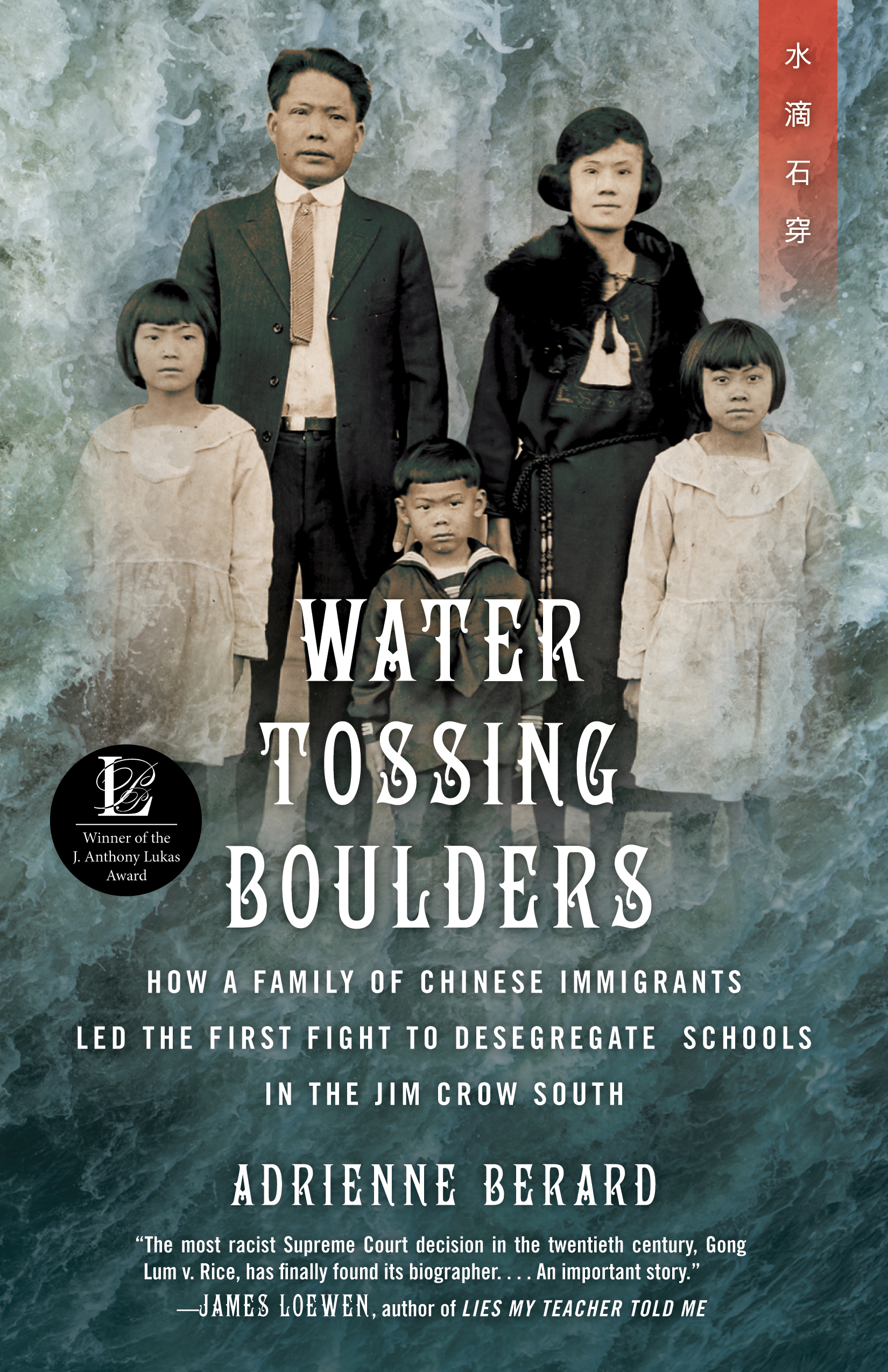

In a new book about on their case, Water Tossing Boulders: How a Family of Chinese Immigrants Led the First Fight to Desegregate Schools in the Jim Crow South, author Adrienne Berard explores how the Lum daughters found themselves discriminated against in Rosedale, Miss., and why their attempt to fight the system had unintended consequences.

When students learn about the Chinese-American experience, the lessons often focus on “the West Coast, the railroads, the history of the 1882 Immigration Act, the riots,” Berard tells TIME. But the history of Chinese-Americans in the South goes back just as far. Shortly after Emancipation, Chinese migrants were brought in as part of the “Coolie trade” to replace slave labor—a coerced, if not forced, migration of indentured servants.

Jeu Gong Lum was part of a wave of immigrants who tried to get around the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (which prohibited Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S.) by sneaking across the Canadian border. He fled to the South, where he had a relative, and where he was less likely to be caught by patrol officers. He came to America as an adult, but married a woman who had come over as an indentured servant at age 10 or 11, Berard estimates. That woman, Katherine Wong, grew up thoroughly acclimated to the American South, socializing with white southerners at church, cooking southern food and speaking and writing English fluently.

After they married, they opened a small grocery store—a popular choice for many Chinese immigrants in the South, as it made them “merchants” and therefore carried special permissions that were prohibited to Chinese laborers. They primarily served an African-American clientele. Their children attended white schools, and when they moved to Rosedale their second daughter, Martha Lum, excelled academically. (She had already been keeping the books for her family’s grocery store since she was 5 or 6.) Still, when she and her older sister Berda arrived for the first day of school in 1924, their second year in Rosedale, they were told to leave and attend the black school in town instead—they were now considered colored.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The Lum family sued to get their daughters back into the white school, making the argument that it was discriminatory to force Asian students to attend a school in which “colored” otherwise meant black. But when a lawyer who was passionate about 14th Amendment issues took on their case, it became something bigger: Earl Brewer wanted to strike a blow against segregation laws in general.

Brewer chose to make Martha the focus of the case since she was such an exemplary student. “The state collects from all for the benefit of all,” he told the Mississippi Supreme Court. “Martha Lum is one of the state’s children and is entitled to the enjoyment of the privilege of the public school system without regard to her race.”

But, though he won the case on a local level, he lost in the state Supreme Court. His work was imperfect, Berard points out. “He changed his argument several times, he didn’t really know what angle he was going at, some of the things he said were really, really racist rhetoric, so I don’t want to paint him as the perfect hero in this story,” Berard says. “But I will say he put a lot on the line.”

Brewer had handed the case to another lawyer by the time it made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, and that attorney—who had never filed a 14th amendment case in his life—put in little effort. He lost in 1927, and the decision was devastating not only for the Lums, but for people of color throughout the country. The unanimous ruling “let Mississippi schools regulate themselves however they want, and define race of their students however they want,” Berard says. “That’s the really horrible thing about this decision: the Lum family aside, this created a precedent for segregation that broadens it, gives it more power.”

By the time Brown v. Board of Ed was fought nearly three decades later, the precedent established in Lum v. Rice was a big challenge for civil rights lawyers to overcome.

Part of the reason Lum v. Rice isn’t better known is that the Lum family lost, Berard says, but their place in history may also be affected by the fact that the family wasn’t fully on the side of civil rights for all. They, like their lawyer, make flawed heroes.

“You want to stand behind the family in one way, because they are making a decision for their children,” says Berard, who interviewed descendants of the Lums for her book. “But at the same time they are clearly making a racist decision. Whether it’s part of what was considered normal at the time or not, I don’t think you can let them off the hook for that very obvious fact that they did not want their daughters going to school with black children.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com