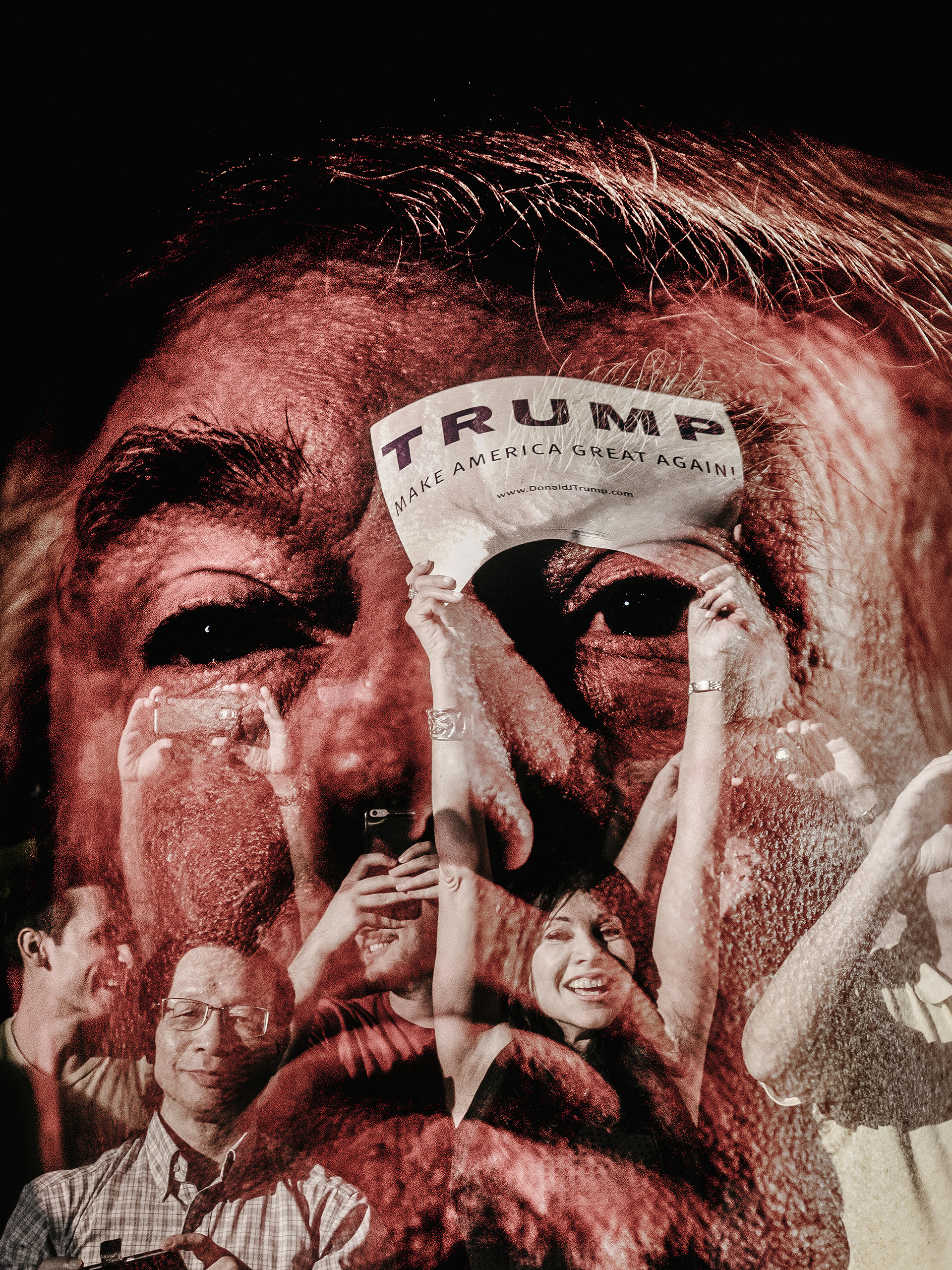

Allan Thiel likes to stay informed. That’s how he knows that President Barack Obama is a foreign-born Muslim who cheated his way into the presidency in order to promote a globalist “utopia.” A retired factory worker and born-again Christian, he waits on the floor of the Greenville, N.C., convention center for Donald Trump to take the stage, holding up his phone so others can see the latest headline he had just read: “Obama Announces Plans for a Third Term Presidential Run.”

The story is not true. But right now, in this moment, Thiel believes it, just as he believes that climate change is a hoax, that Islam is being promoted in American schools and that the government has been bought out by drug cartels. He says that “people aren’t being taught history anymore” and “they’ve dumbed everybody down.” As the campaign soundtrack roars and the energy builds, he offers a version of American history that cannot be found in the historical record. “Our country has never had any problems for the last 200 years,” he says, shaking his head. “We’ve never had a problem with guns or racism until the last eight years.”

To simply grade the accuracy of Thiel’s statements misses the point, because Thiel’s beliefs do matter. They show up in double digits in national polls and belong to a reality shared by many Trump supporters TIME interviewed in North Carolina over a few days in September. Here you find deep frustration with the state of the nation, the direction of the economy, the consequence of global trade and the prospect of a President Hillary Clinton. But in dozens of interviews, voters also made arguments built on claims unsupported by facts, often peddling debunked conspiracy theory as plausible truth.

“I never once in history have seen white people riot,” says Adam Watkins, a white Trump supporter chatting in nearby Wilmington, N.C., the day of the rally. As it happens, Wilmington was the site of one of the nation’s most famous race riots, when hundreds of whites overthrew the elected government in 1898, killed more than a dozen black residents and burned down the offices of the only local black newspaper. There is a monument in the center of town commemorating the event. “In the 1960s they had a lot of riots involving black people,” Watkins continues. “No whites.”

At a nearby café, Roxanne Noble, a registered nurse, calmly explains over an egg sandwich why she can’t ever vote Clinton: Vince Foster, a onetime White House aide, was murdered to hide the Clintons’ secrets. “I have followed the corruption, the deaths of people working with her,” she says. “How could anyone who has educated themselves vote for this person?”

Five official investigations–by U.S. Park Police, the Justice Department, House Republicans, Senate Democrats and special prosecutor Kenneth Starr–ruled Foster’s death a suicide. But there are thousands of web pages that describe fanciful Foster murder-plot conspiracies.

More crucially, Donald Trump, the GOP presidential nominee, has spent years regularly encouraging his followers to doubt much of what is known to be true: that the earth is warming, that Obama was born in the U.S., that the FBI’s decision not to prosecute Hillary Clinton follows prosecutorial precedent. After losing the first presidential debate in September by every scientific measure, Trump and his campaign spent days promoting unscientific reader surveys, including one by TIME, to lay a claim to victory. And back in May, Trump even made common cause with Noble, declaring that Foster’s death was “very fishy.” “I will say there are people who continue to bring it up because they think it was absolutely a murder,” Trump said.

No presidential candidate in modern memory has played footsie with fantasy like this during a campaign. But for Trump, casting doubt on what is demonstrably real and lending credence to what is not has become a core appeal of his campaign. Democratic societies function on faith in strangers–in police and judges to do their job without fear or favor; in government agencies to fairly enforce laws; and in experts of all stripes, from scientists to journalists to economists, to accurately report on what is happening in the world. Trump’s central argument is that faith has been lost, and he has put himself forward as the only solution. “We will never fix our rigged system by relying on the people who rigged it in the first place,” he says, when he takes the stage in Greenville.

One of the first casualties of this worldview is the very ability to have a national debate with a common set of facts. When Trump talks about a rigged system, he is not just accusing Clinton of corruption. He is talking about the institutions that facilitate democracy: Election Day poll workers, who he says may try to swing the election for Clinton; the Federal Reserve, which he has accused of favoring Obama; the debate moderators, who he has falsely accused of being Democrats; and the rest of the national press, including the pages you are reading right now, which he claims function as agents of the established elite. “She is being protected by the media, by the press, like nobody has ever been protected in the history of this country,” he tells the Greenville crowd. “Me on the other hand, it’s a total pile-on.”

So it makes sense when Thiel grabs hold of the new headline on his cell phone on the convention floor. The false story about Obama’s plans to abolish the 22nd Amendment appears to have originated about two years ago on a satirical site called the National Report, which publishes hoax headlines like “ISIS Claims Responsibility for Sinking Titanic.” But in a world where nothing and no one can be trusted, the site looks just as real as anything else. In Trump’s America, if people are saying it, it might be true.

Four years ago, the nation was embroiled in a very similar argument over the role of truth and accuracy in a presidential election. The campaigns of Barack Obama and Mitt Romney accused each other of lying to voters, and fact checkers said the misstatements were as bad as they had ever seen. On balance, Romney’s deceptions were frequently more brazen, but Obama was not innocent. He made the false charge that Romney wanted to outlaw abortion in all cases a centerpiece of his campaign.

But the truth wars of 2012 now seem quaint in retrospect. The fibs mostly concerned policy, and both candidates limited their criticisms of the press, politely working the referees on the sidelines.

Since the country’s founding, pamphleteers have spread lies to influence voters before elections. But in 2012, it became clear that there was no institution that could enforce norms of truth telling during the campaign. Fact checkers could rule that a candidate had his pants on fire, but voters would be far more likely to hear the deception in a campaign ad than the judgment in a newspaper.

No one was better prepared to exploit this systemic weakness than Trump, a salesman who had long become comfortable with manipulating reality and dabbling in falsehood. In his first book, The Art of the Deal, he boasted of the value of “truthful hyperbole,” and in sworn depositions through the years, he had been rather transparent about how he understands the fungibility of facts. Whereas most politicians recoil from the public shame that comes with inaccuracy, Trump had taken the opposite lesson. Reality, he argued under oath in a 2007 deposition, could be up to him. “My net worth fluctuates, and it goes up and down with markets and with attitudes and with feelings, even my own feelings,” he said.

Trump has long done business this way. Just as a condo salesman can make a building more valuable with a pitch that attracts a higher price, Trump’s rise to political prominence depended on embracing fantasies early on. And he did it with techniques that politicians have long avoided: He would conflate sources to make incredible information seem credible. He would use sarcasm to insert falsehoods into the public mind, joking most recently about the possibility, unsupported by any evidence, that Hillary Clinton had been unfaithful to her husband. And he would disavow authorship of the lies he shared. After he retweeted the racist libel that blacks kill more than 80% of white murder victims, he refused to correct the information. “There’s a big difference between a tweet and a retweet,” he told TIME.

For her part, Clinton has been caught misleading voters about her email arrangement, her handling of classified information and her policy prescriptions. But her violations are of a different kind than those of Trump, whose favorite arguments are often the stuff of fiction. He says he opposed the Iraq War before it began, even though his only public utterances at the time were supportive. He insinuated that “thousands and thousands” of Muslims in New Jersey had celebrated on Sept. 11, which did not happen.

“What we are realizing is how much of the normal behavior of campaigns is determined by norms,” says Brendan Nyhan, a political scientist at Dartmouth who has long studied the issue of accuracy in politics. “The system isn’t built to withstand a presidential campaign like his.”

In the final weeks of the campaign, such falsehoods can easily dominate a news cycle. But their biggest impact probably occurred before he started his campaign. For years, starting in 2011, Trump spread doubts about Obama’s birthplace in Hawaii, a charge designed to dismiss the nation’s first black President as a potential foreigner. In September, Trump finally denounced his own birther crusade, only to replace it with another deception: that it was Clinton and her 2008 campaign that started the birther movement, which they did not.

Though Trump now admits the truth of Obama’s birth, the damage has been done. One Trump supporter in Fayetteville, N.C., who later asked not to be named, tried to settle an argument last month over Obama’s birth by asking his phone’s virtual assistant where the President was born. When the woman’s voice answered with the name of the hospital on Hawaii, he rolled his eyes, asked again and got the same response. Frustrated, he threw his phone down on the counter. Polls have consistently shown that 20% of Americans refuse to accept that Obama was born in the U.S.

Trump may have become a champion of an alternate reality, but his claims have taken flight at a time when the nation has lost the common public spaces where we once debated our future. In late September, the conservative website Breitbart got hold of a nearly 500-page report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine about the economic consequences of immigration. Breitbart, which was recently run by Stephen Bannon, Trump’s current campaign CEO, cherry-picked a statistic from a theoretical section of the report to produce this headline: “National Academies Study Shows $500 Billion Immigration Tax on Working Americans.”

The report’s authors quickly explained that that calculation failed to take into account the full impact of the economic effects of immigrants on American wealth. But depending on how the news comes to your smartphone, you might have seen that headline or the contradictory ones that most news organizations used, reflecting the report’s final conclusion. “Immigrants Aren’t Taking Americans’ Jobs, New Study Finds,” ran the New York Times.

If you’re well versed in the subtleties of 2016 media, you’d know about Breitbart’s political leanings and take that $500 billion nugget with a boulder of salt. But if you’re an ordinary American, you might not know which of these two versions is the truth: you’d just believe the one that sounds most true to you. And you might believe, as Breitbart suggested in subsequent stories, that the National Academies were trying to hide the conclusions of their own report.

It’s a problem of quantity as much as quality: there is simply too much information for the public to accurately metabolize, which means that distortions–and outright falsehoods–are almost inevitable. The same technology that gives voice to millions of ordinary citizens also allows bogus information to seep into the public consciousness. Mainstream journalists are no longer trusted as gatekeepers to verify the stories that are true and kill the rumors that are false.

Which means that phony conspiracy theories are often mixed in with accurate journalism and history. Just look at former Trump adviser and conspiracy theorist Roger Stone’s book The Clintons’ War on Women, a treatise filled with conjecture and conspiracy, which has jumped to No. 27 on the Amazon best-seller list in the Presidents & Heads of State biographies category, near titles by established historians like Jon Meacham and Doris Kearns Goodwin.

At the same time, the information revolution has eroded faith in the institutions that once served as arbiters of reality. Mainstream journalism, government reports and academic research have lost the weight of truth for much of the population. From 2006 to 2016, Americans became 10% less likely to have faith in Congress or the media. In 1958, almost three-quarters of Americans trusted the government most of the time–now, that number is down to 1 in 5. A recent Pew study found that 70% of Democrats trust climate scientists, compared with just 15% of Republicans–and only 16% of Republicans believe the factual statement that scientists are in a near unanimous consensus on climate change.

So instead of institutions, people look to their social networks for information, and social networks are where conspiracy theories thrive best, egged on by Trump’s enormous social power. Passed from Facebook to Facebook, retweeted by thousands of anonymous accounts, ideas can spread quickly without verification or context. People tend to share content that gets the most extreme reactions, which means a terrifying but untrue story will be shared more widely than a mildly alarming but accurate one.

And Trump has done his best to discredit the few remaining news organizations that display any rigorous adherence to fact. He regularly tweets at the “failing @nytimes” and smears its “disgusting” and “dishonest” coverage. He calls out CNN for “phony reporting” and slams its “boring anti-Trump panelists, mostly losers in life.” He is quick to attack anybody who exposes his falsehoods, painting legitimate news sources as biased and phony.

Five years ago, people could tell whether a news source was legitimate by looking at the site’s home page for context. Now all the credibility of publishers is often discarded. In April, Trump announced that Ted Cruz’s father was involved with Lee Harvey Oswald, the accused assassin of John F. Kennedy, based on a unsubstantiated, grainy photo published in the National Enquirer. “What was he doing with Lee Harvey Oswald shortly before the death?” Trump asked. “It’s horrible.”

In 2005, the comedian Stephen Colbert, who now hosts The Late Show on CBS, had mocked political deception as “truthiness,” or half-truths with one foot in reality and one foot in fiction. “You know what the facts are, but you go with what feels more truthful to you,” Colbert told TIME, explaining the technique.

But in recent months, Colbert, a fierce satirist of Trump, has come to believe that his old critique no longer applies: “Trump’s [version] is completely divorced from reality.” How does it feel to watch the new version of truthiness take over America? “How does a parent feel when their baby ends up in a police lineup?” he asks.

Whatever the outcome in November, none of this will end. A Clinton victory will not usher in a return to truth and accuracy or restore American faith in institutions. If anything, a Trump loss could convince his supporters that the system is just as rigged as they’ve been led to believe it is. Pandora’s box has been opened, and once enough people believe something false, it begins to sound almost true.

But even people who believe the conspiracy theories still have a sense that their reality is warped. Sitting at a bar in Wilmington, N.C., Gary Wilson tries to explain his skepticism. “There’s a lot of conspiracy theorists out there, and some of them are goddamn wack jobs,” he says, before explaining his process for figuring out what to trust. “If I hear it from several different sources, I tend to believe it,” he says. “‘Let me think about that myself, let me see if I can find that one conspiracy even slightly believable.'”

The popular New World Order theory passed that litmus test: Wilson believes that global elites are conspiring with the U.N. to create a world government that will act like Big Brother to ordinary people, and that trade pacts are the first step in the process. (The U.N. is not involved in the enforcement of trade deals, which are signed as agreements between participating nations.)

“I just believe it,” he says. “Where did I find my sources? Alex Jones is a good one.” Jones is the host of a radio show that is an entertaining mixture of outrage and conspiracy theory; he has become a champion of Trump. At various times, Jones has claimed that the government has poisoned juice boxes to make citizens gay, that the Bush Administration was complicit in the Sept. 11 attacks and even that Trump was a secret agent working for Clinton by sinking Republican chances of winning the White House. “Your reputation is amazing,” Trump said on Jones’ show in December. “I will not let you down.”

Wilson says he began to notice four or five years ago that 9/11 had been an inside job after “a friend of mine turned me on to a couple websites.” He hates both candidates but says that if it comes down to it, he’ll have to vote for Trump. “A lot of what he says is the truth. He doesn’t bullsh-t,” Wilson says. “He has no problem saying sh-t that me and him would be saying at the bar.” And this is not a place where anyone is asked to prove their assertions.

–With reporting by TESSA BERENSON, PHILIP ELLIOTT and ZEKE J. MILLER/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com