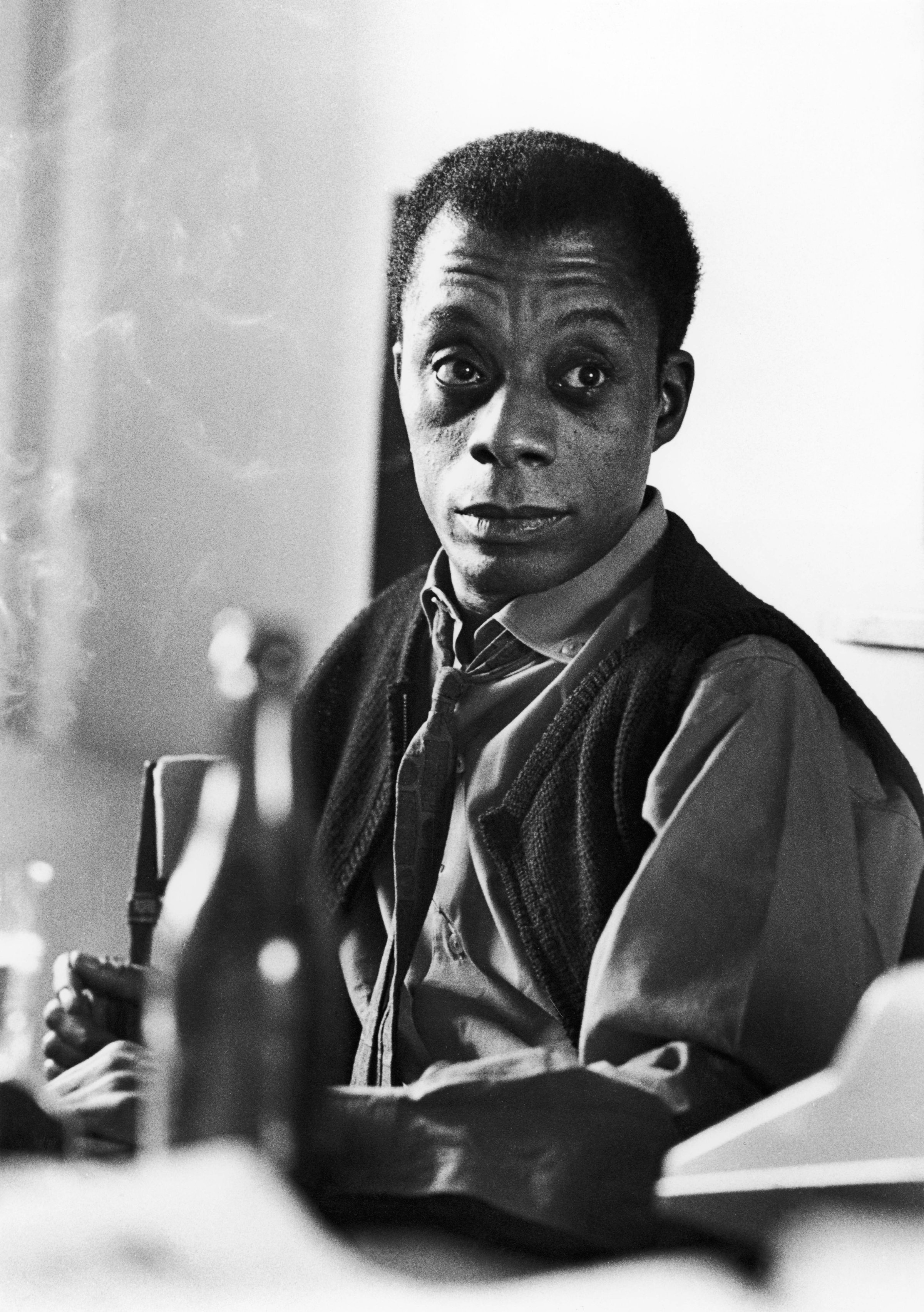

James Baldwin is everywhere. To account for the latest disasters around race in this country—grief over the death of another black person at the hands of police; the fact that we have vomited up the likes of Donald Trump—activists often reach for him. Baldwin circulates. His words inspire on social media; his phrases speak from T-shirts; his face covers a throw pillow on Etsy. But apart from his marketability—that people can use him as an avatar of supposed seriousness—what does Baldwin offer us in this moment? What does he force us, as Americans, to confront?

In Teju Cole’s brilliant new book of essays, Known and Strange Things, he writes of a trip to Selma, Ala. This essay, like much of the book, reveals Cole’s extraordinary talent and his capacious mind. But one immediately gets the sense that, for him, the American South is primarily a landscape of tragic memories. The distinctive sounds and smells of the region don’t find their way to the page. No laughter. Just sadness, triggered by the Edmund Pettus Bridge and the violence exacted there.

Cole asks, “Long after history’s active moment, do places retain some charge of what they witnessed, what they endured?” As he walks the streets of Selma, listening to John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” that past comes into full view. It could not be otherwise. “History,” Cole writes, “won’t let go of us. We’re pinned to it.”

The formulation reminds me of James Baldwin. It certainly echoes Cole’s engagement with Baldwin throughout the book—one of embrace and of distance. For example, he repeatedly returns to Baldwin’s essay, “A Stranger in the Village.” He does so not to align himself with Baldwin’s expressed feelings of alienation in a remote Swiss village that had never seen “a negro.” Instead, his invocation of the essay occasions a moment of contrast: that his anxieties are not Baldwin’s. The reader learns that Cole is an American—a Black American—of a different sort.

He writes of his visit to Leukerbad, the place in Switzerland where Baldwin finished his classic novel, Go Tell it on the Mountain: “They’ve seen blacks now; I wasn’t a remarkable sight.” And, unlike Baldwin, Cole does not feel that he resides on the outside of the Western tradition looking in. He possesses it as his own. William Shakespeare is as much his as is Wole Soyinka. He writes, “I disagree not with [Baldwin’s] particular sorrow but with the self-abnegation that pinned him to it.”

Known and Strange Things refracts that difference with unadorned brilliance and deft strokes. Cole’s worldliness, as seen in the wide range of his reading and in his inquisitive presence all over the world, jumps from every page. Epiphanies abound. But Baldwin and his questions about history, memory and identity still haunt.

In August 1965, Baldwin penned an essay for Ebony magazine titled “The White Man’s Guilt,” a relentless indictment of white America. Of course, 1965 was a difficult year. Malcolm X was assassinated in February. In March, the world witnessed the brutality of Selma. And on Aug. 11, Watts exploded. The special issue of Ebony—black with a white face in profile, and a cover line announcing “The White Problem in America”—hit the stands as people took to the streets. The magazine signaled that something deep down had changed. In it, Baldwin demanded a wholesale confrontation with a history that white America desperately avoided. As he wrote:

White man, hear me! History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us.… And it is with great pain and terror that one begins to realize this. …In great pain and terror because,…one enters into battle with that historical creation, Oneself, and attempts to recreate oneself according to a principle more humane and more liberating…

For Baldwin, white America needed to shatter the myths that secured its innocence. This required discarding the history that traps us in the categories of race; histories that justify the belief that white people matter more than others. He echoes here a critical point in Notes of a Native Son (1955): “Now, as then, we find ourselves bound, first without, then within, by the nature of our categorization.” Those categories (like ‘nigger,’ ‘welfare queen,’ ‘thug,’ and the ‘white people’ who invented them) arrest our ability to recreate ourselves and to imagine a more just world. Instead, we’re bound to a kind of thinking that orders the world on the backs of black people and fixes the place of white people in legend and myth. But, as Baldwin wrote in The Fire Next Time (1963), “The American Negro has the great advantage of having never believed that collection of myths to which white Americans cling.”

“White Man’s Guilt” draws on much of Baldwin’s earlier thinking, but the tone of the essay is decidedly different. Rage seeps through the page. Loss shapes every sentence. Perhaps this reflects his grief over the murders of Medgar Evers and Malcolm X. Their deaths, along with the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., frame one of his most powerful books, No Name in the Street (1972), where memories of loss remind us of the broken souls hidden beneath our cherished form of life. But, even with the shift in tone, the claim about history and about who we are as creatures of history remain. For Baldwin, white people seemed hopelessly trapped by their myths, and others catch hell because of that fact. As he wrote in Ebony, “people who imagine that history flatters them are impaled on their history like a butterfly on a pin and become incapable of seeing or changing themselves, or the world.”

There’s that image again: we’re pinned to a history—or, perhaps, a lie—that keeps us from creating better selves, a better world. Stuck right where we are.

“White Man’s Guilt” ends with a reference to Henry James’s novel, The Ambassadors. We are urged to live and trust life. “[I]t will teach you, in joy and sorrow, all you need to know.” For Baldwin, black jazz musicians know this; the old wisdom of black life reflects this. But white people, at their peril, do not know this and do not want to know it. They are “barricaded inside their history.”

The turn to Henry James is telling. According to Baldwin’s biographer, David Leeming, both shared a central theme: “the failure of Americans to see through to the reality of others.” That blindness and moral failing, especially with regards to black people, stood at the heart of the problems of this country, and it blocked the way to a more democratic future. As Baldwin stated, “freedom [meant] the end of innocence.”

Baldwin’s writing does not bear witness to the glory of America. It reveals the country’s sins, and the illusion of innocence that blinds us to the reality of others. Baldwin’s vision then requires a confrontation with history (with slavery, Jim Crow segregation, with whiteness) to overcome its hold on us. Not to posit the greatness of America, but to establish the ground upon which to imagine the country anew.

That grand project begins with each of us engaged in the arduous task of self-creation—to break loose from the stranglehold of white supremacy and to recreate ourselves in the light of what is possible. It involves a relentless confrontation with that “historical creation, Oneself.” This, Baldwin believed, was a revolutionary act. As he wrote in “Black Power” (1968): “[W]hen a black man[sic], whose destiny and identity have always been controlled by others, decides and states that he will control his own destiny and rejects the identity given to him by others, he is talking revolution.”

Perhaps this is the allure of James Baldwin: he takes us to the heart of what ails this country, and he does so while insisting on the individuality of black people. We aren’t reduced to mere sociological categories. Instead, in his hands, we are flesh and blood, with fleshly desires and profound sorrows. Vulnerable and powerful all at once. Baldwin’s writing makes space for us to be exactly who we are, in all of our complexity, and who we desire to be in spite of what white folks think about us.

And, yet, history haunts.

Jesmyn Ward’s new anthology, The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race, reveals the burdens of history, memory, and identity in these troubling times. The title explicitly connects the book to Baldwin’s witness. For Ward, his words, especially in The Fire Next Time, served as a balm in the aftermath of the death of Trayvon Martin (and of so many others). Reading Baldwin affirmed the full scope of her—of our—humanity. Ward has curated a book, with some of the best contemporary writers of color in the country, to help us feel and think our way through this current moment. Baldwin looms large here—as inspiration and as a long shadow.

For most of the authors, history funds the present and its excavation reveals how we are pinned in. But this isn’t an abstract consideration. Throughout the book the reader confronts the stark facts of black life and the difficult task of actually living those facts: of what it means to walk the cobbled streets of a slave market that has been removed from view, to raise children knowing that they can be killed simply because they are black, to know the dangers of white rage and to tell its long history, as Carol Anderson writes; to keep track of those sources, like Grandma’s love and the music, that made you who you are, as Kiese Laymon writes. To laugh at the silliness of the categories that trap us, to be in and long for those places that feel, if just for a moment, like home.

I was particularly taken by Garnette Cadogan’s essay. Just in the mere act of walking the city he takes heed of the openings and limitations of what it means to be black here: that at any moment, and simply because of the fact that you’re black, you can be an object of suspicion. Cadogan cleverly upends Walt Whitman’s walking. “Instead of meandering aimlessly in the footsteps of Whitman, Melville, Kazin, and Vivian Gornick, more often I felt that I was tiptoeing in Baldwin’s….” He learned Baldwin’s lesson: this is a different kind of song of America.

The book ends with Edwidge Danticat’s letter to her daughters. It is an echo of Baldwin’s letter to his nephew in The Fire Next Time. Danticat writes: “we realize the precarious nature of citizenship here: that we too are prey, and that those who have been in this country for generations—walking, living, loving in the same skin we’re in—they too can suddenly become refugees.”

And, Danticat’s formulation brought me back to Teju Cole. These are different black Americans; their histories, intertwined as they are with my own, complicate any easy invocation of black identity in this country. They complicate James Baldwin. He would expect nothing less. Our times have changed in so many ways. Even so, as Danticat’s letter shows, Baldwin’s insight remains: that, as we fight our evils, we must confront, without flinching, the history of this country that continues to shape who we are and limit who we can be. In great pain and terror, we have to do this even as we bury our dead if we—and I mean all of us—are to be truly free.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com