Five-fifty leading groups representing 10 million scientists called Wednesday on presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump to address key science-related policy issues in advance of the November election.

The coalition, which includes the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAS) and the National Academy of Sciences, among other organizations, highlights a list of 20 topics like climate change, vaccinations and public health.

“Collectively, those issues have at least as much impact on voters’ lives as the economic policy and foreign policy candidates are used to debating,” says Shawn Otto, a science advocate and chair of the Science Debate nonprofit.

This year’s election comes at a pivotal moment for many issues of concern for the scientific community. Climate scientists, for instance, have warned that the next several years will be crucial to any effort to stem catastrophic global warming. Trump has called climate change a “hoax” and promised to “cancel” the Paris Agreement on climate change. While doing so would be easier said than done, the agreement is structured in such a way that a president could simply choose not to enforce it.

The White House also sets funding priorities through its federal budget requests, providing federal tax dollars for virtually every area of scientific research. And the President directs agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Departments of Energy and Interior.

In previous administrations, funding for science has been uneven. The 1990s under Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton saw a bipartisan initiative to double funding for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), while President George W. Bush took a different approach, appointing officials with little scientific background to key positions, according to Otto.

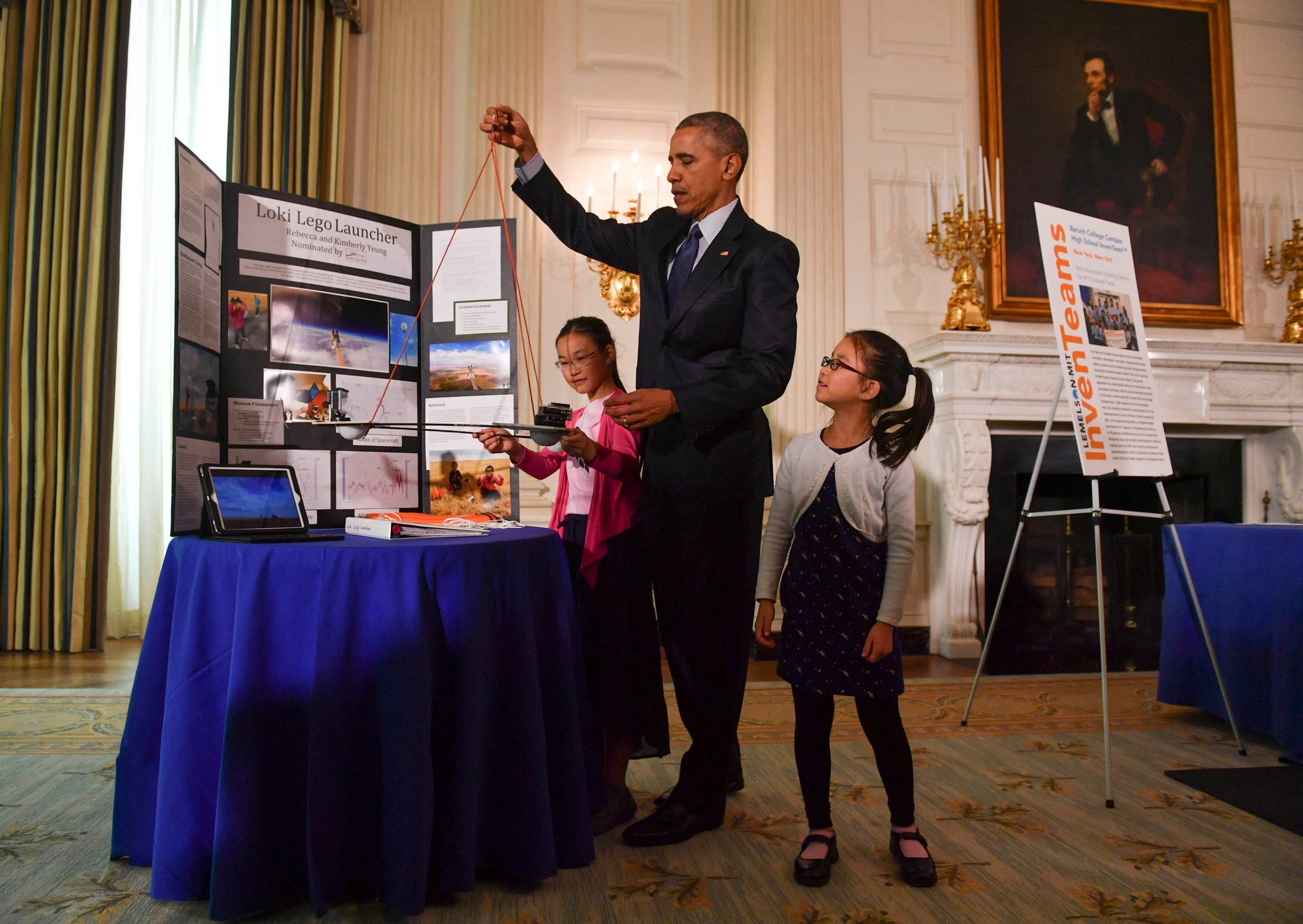

President Obama has been a prominent advocate of addressing a range of science issues despite coming to the White House with little background in the area. Beyond his focus on policies like the Clean Power Plan and an effort to address the opioid crisis, Obama has also brought attention to science with efforts like the White House Science Fair.

The questionnaire from the scientific groups is non-partisan and both major party nominees responded to a similar request 2008 and 2012. Some scientists and science policymakers have taken a position against Trump, particularly his energy and environmental policies. Two former GOP EPA heads endorsed Hillary Clinton this week and others have criticized Trump’s energy plan.

“Presidents, through the face of government and its institutions, set the tone of the public discussion around science,” says Otto. “Science is never partisan, but it is always political.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com