Saul Alinsky graced headlines on Wednesday, after retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson named him as one of Hillary Clinton’s mentors and heroes in a speech to the Republican convention the night before. “And, her senior thesis was about Saul Alinsky. This was someone that she greatly admired and that affected all of her philosophies subsequently,” the former presidential candidate told the crowd. “Let me tell you something about Saul Alinsky. He wrote a book called, Rules for Radicals. On the dedication page it acknowledges Lucifer, the original radical who gained his own kingdom.”

Alinsky’s book, while it does contain an epigram that quotes Alinsky himself referring to Lucifer as “the first radical,” is dedicated “to Irene,” his wife. But Alinsky, a community activist who wrote about organizational tactics for grassroots groups, was in fact the subject of Clinton’s 1969 senior thesis at Wellesley—and clearly remains to this day a subject of much debate.

So, who was Saul Alinsky, and what did he do?

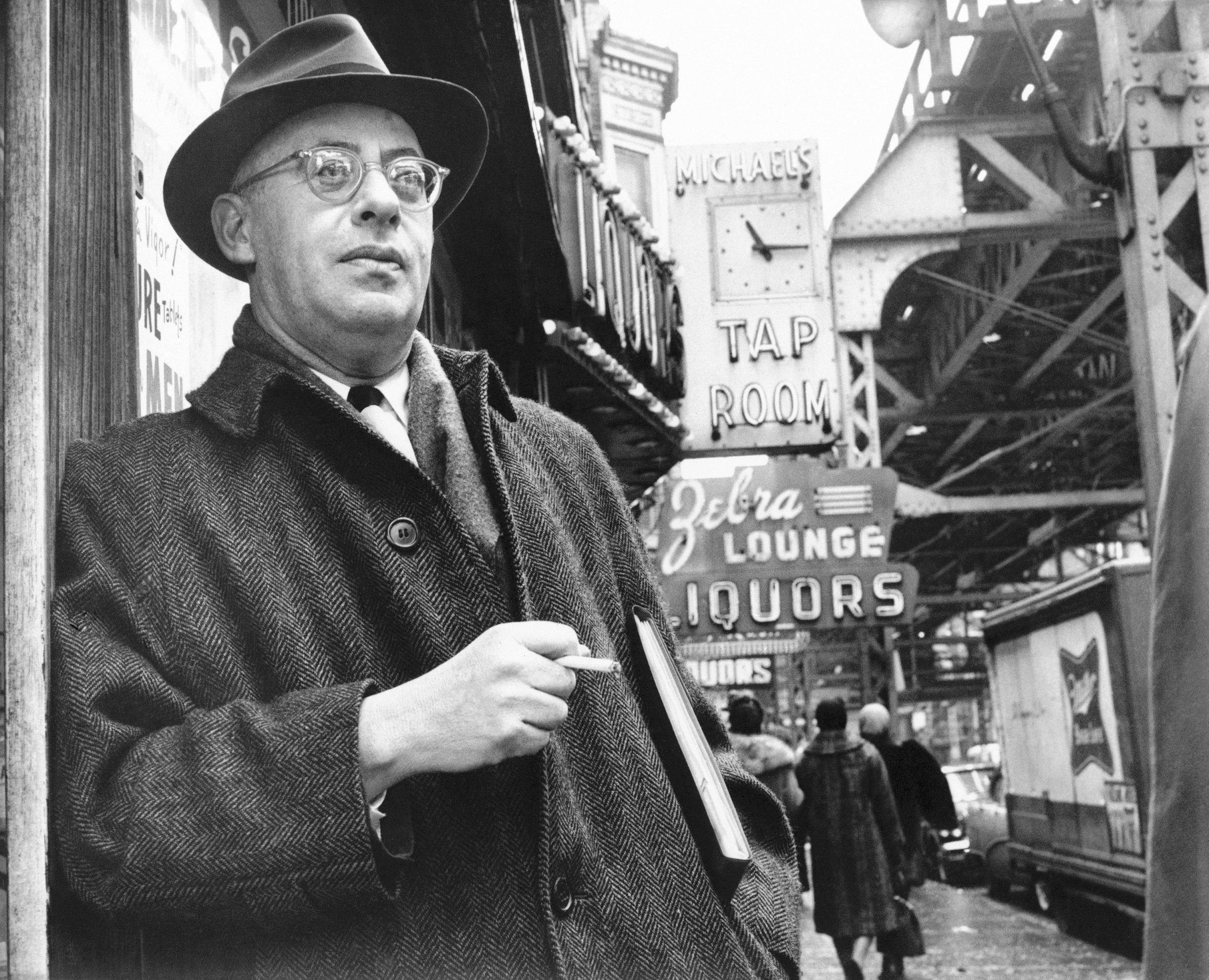

TIME’s first reporting on Alinsky, who was born in 1909, goes all the way back to 1939, when he was named as the organizer of the Back-of-the-Yards Neighborhood Council, a pro-labor and anti-fascist group that had been brought together by the Chicago native and University of Chicago graduate—who, the magazine noted, “once lived with the Capone gang” for social research. At that point, Alinsky had been getting involved in labor organizing for years, as part of a career that has been traced back to when he first got involved with disputes among miners’ groups.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Reports from the 1960s recognized Alinsky as for his work in community organizing throughout Chicago and the country. In 1965, Alinsky traveled “from city to city advising the poor on how to organize for uplift” amid the “new poverty” that had hit the U.S. at that time. And neither party was immune from his barbs: Alinsky became a vocal critic of President Lyndon Johnson’s administration’s famous antipoverty programs; in 1966, Alinsky called the War on Poverty “a prize piece of political pornography.”

But it was in 1970, in an essay called “Radical Saul Alinsky: Prophet of Power to the People,” that TIME attempted to distill the Alinsky mythos:

Saul Alinsky has possibly antagonized more people—regardless of race, color or creed—than any other living American. From his point of view, that adds up to an eminently successful career: his aim in life is to make people mad enough to fight for their own interests. “The only place you really have consensus is where you have totalitarianism,” he says, as he organizes conflict as the only route to true progress. Like Machiavelli, whom he has studied and admires, Alinsky teaches how power may be used. Unlike Machiavelli, his pupil is not the prince but the people.

It is not too much to argue that American democracy is being altered by Alinsky’s ideas. In an age of dissolving political labels, he is a radical—but not in the usual sense, and he is certainly a long way removed from New Left extremists. He has instructed white slums and black ghettos in organizing to improve their living and working conditions; he inspired Cesar Chavez’s effort to organize California’s grape pickers. His strategy was emulated by the Federal Government in its antipoverty and model-cities programs: the poor have been encouraged to participate in measures for their relief instead of just accepting handouts.

A sharing of power, thinks Alinsky, is what democracy is all about. Where power is lacking, so are hope and happiness. Alinsky seeks power for others, not for himself. His goal is to build the kind of organization that can dispense with his services as soon as possible. Nor does he confine his tactics to the traditionally underprivileged. Although he has largely helped the very poor, he has begun to teach members of the alienated middle classes how to use power to combat increasingly burdensome taxes and pollution.

At the time, Alinsky’s goals were to build power and share it with others—and not only people who were most obviously in need of it. “Although he has largely helped the very poor, he has begun to teach members of the alienated middle classes how to use power to combat increasingly burdensome taxes and pollution,” the profile noted.

Alinsky was never one to shy away from conflict. To prove a point about the need for better city sanitation services in poor neighborhoods, he had garbage brought to an alderman’s house and rats to city hall. Some saw his tactics as evidence of that he was a bit of a jokester, who had mastered the technique of complaining with “a touch of imagination.” (His influence carries on: this year, Bernie Sanders supporters said they are planning a “fart-in” at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia to protest Clinton’s nomination — an idea attributed to Alinsky, who once threatened the same form of protest in Rochester, N.Y.) Others, however, saw him thumbing his nose at American society; in the last presidential election, Barack Obama’s Chicago-organizer link to Alinsky was used to paint him, as Newt Gingrich put it, as “the most radical President in American history.”

But Alinsky, clearly, was all right being the subject of conflict—and with the difficulty of pinning down his legacy. Asked by TIME in 1968 whether he was a true revolutionary or a person who wanted to work within the system, his answer was a complicated one.

“I would destroy [the system] if I knew of a better one,” Alinsky told TIME. “The problem is that I can’t find a better one.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mahita Gajanan at mahita.gajanan@time.com