America is many things. A land. A concept. A home. Ever since our nation’s founding in Philadelphia in 1776, people have sought to define the United States. But America is unique—hard to categorize or describe. One way to try is through some of the seminal entities, items and ideas that were born or nurtured on this soil. These are what a new special edition of TIME calls “American originals.”

For the past 240 years (or longer, really), Americans have been building, tinkering, inventing, singing, dancing, writing, playing, working, imagining and reimagining themselves and this country, all within the context of a notion: the American dream. This is a country of seekers and creators eager to see and influence what lies ahead. Yet attempting to gather all that is original about America would be like trying to canvass every step of the land that the explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the members of their Corps of Discovery trekked across in the early 19th century: too vast, too overwhelming.

We restricted ourselves to 100 originals. It wasn’t easy. Discussions of what to include on the list invariably led to passionate debate: Which movie, The Wizard of Oz or Gone with the Wind? Which camera, Kodak or Polaroid? To make our decisions, we thought first about what is essential and what has changed society.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In the end, we hope we have amassed a list that is not only original but also includes things that have had a profound influence on the country and, often, the world. We hope that within these pages you will learn some new things about your favorite American originals, as well as come across a few others that will join your personal best list.

Find more in TIME’s special edition 100 American Originals: The Things That Shaped Our Culture. Available at retailers and at Amazon.com.

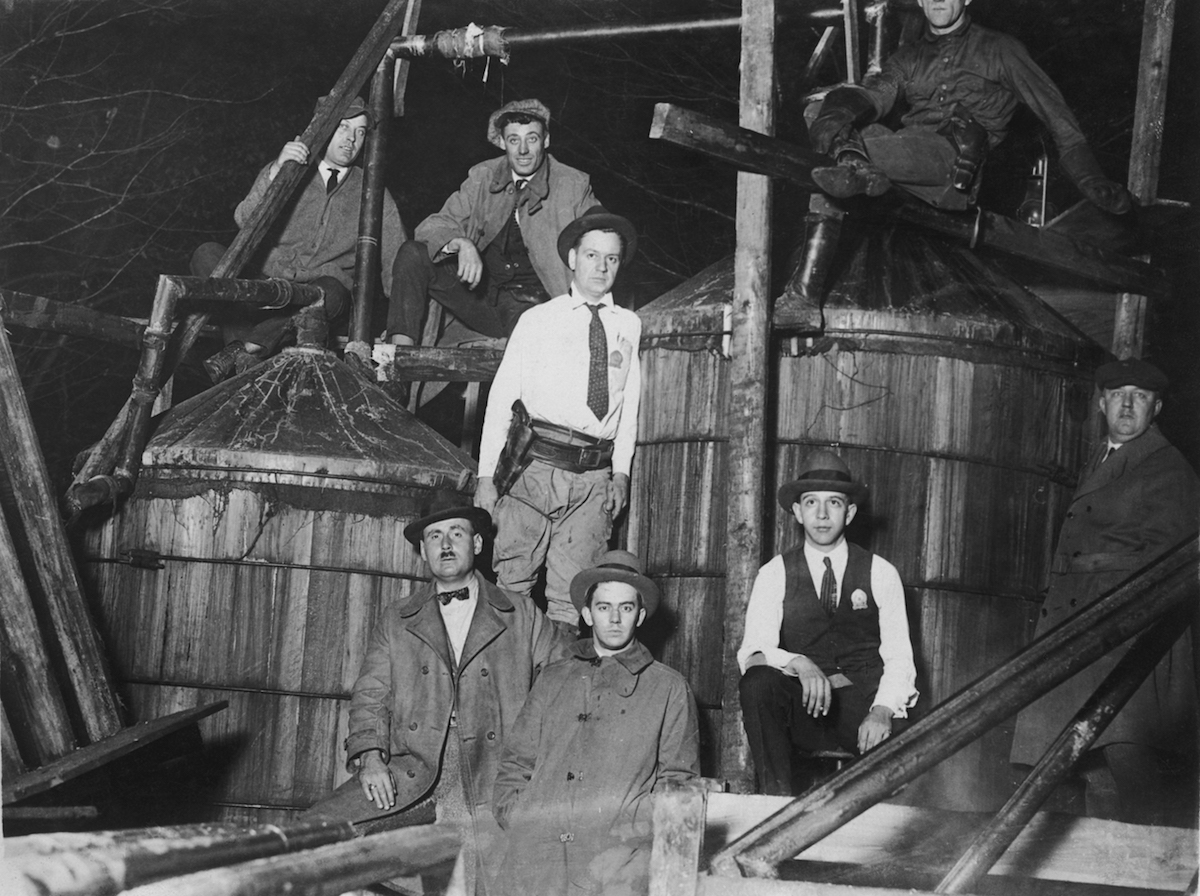

The Still

The term comes from “distillation,” and in practice it refers to a way to produce hooch with a boiler (to cook the mash) and a condenser (to cool the resulting vapor). However delectable or rotgut the spirits they produce, stills call to mind days of moonshine, illegal backwoods liquor from Appalachia and resistance to government meddling.

The struggle started when President George Washington had to confront armed farmers and distillers opposed to a federal excise tax. To quell the Whiskey Rebellion of the 1790s, the president dispatched Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to western Pennsylvania with 12,950 men. As word of their approach spread, the uprising evaporated. Moonshine—which was often produced at night so as not to be discovered—continued to prosper in the South in Virginia, Kentucky and the Carolinas. At the same time that federal revenuers tried to shut down illegal stills, citizens in the 19th and early-20th centuries advocated for the banning of all liquor. As a result, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was enacted in 1920, prohibiting the manufacture, transportation and sale of intoxicating drink. And while the law mandated a bone-dry land, it created a thriving market for those willing to cook up moonshine, mix batches of bathtub gin and bottle home brew. Stills were in.

Production couldn’t keep up with demand, though, leading to the rise of organized crime, as gangsters such as Al Capone, Dutch Schultz and Charles “Lucky” Luciano set the stage for modern crime syndicates. The passage of the 21st Amendment in 1933 ended Prohibition. Even so, 10 states still have dry counties, 15 other counties are partly dry, and there is a thriving market for DIY backyard and countertop stills of varying types and styles, now available through Amazon and deliverable by the U.S. Postal Service.

Ketchup

The average American consumes more than a pound of ketchup per week—a pound!—slathering it on hamburgers, French fries, hot dogs and eggs. Its name comes from the Hokkien Chinese word kê-tsiap, and the puree of tomatoes, peppers, onions, vinegar and spices started as a fermented-soybean-based fish sauce. Dutch and English sailors brought it home in the 17th century, but at the time no one grew soybeans in Europe. Cooks seeking to re-create it tried mixing in oysters, anchovies, elderberries and walnuts. Once ketchup arrived in America, tomatoes were used, and the condiment began being sold in bottles during the 1850s. Its popularity took off after the Civil War, with the New York Tribune intoning in 1896 that it sat “on every table in the land.” Firms such as Heinz, Hunt’s and Del Monte came out with their own versions, and the unrelenting expansion of fast food brought about more varieties. French chefs might scoff at ketchup, but its popularity has spread throughout Europe, South America and Australia—and back to China and the rest of Asia.

The Potato Chip and the Twinkie

Thomas Jefferson enjoyed sliced, fried potatoes while in France, so when he was back state-side, he had his chef prepare them. In 1853 George Crum was the cook at Moon’s Lake Lodge, a resort in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., where many diners liked the way he prepared his version of those french-fried potatoes. One day, however, a guest complained that the potatoes were too thick. Annoyed by the criticism, Crum sliced some potatoes paper-thin, boiled them in oil and, when they crisped, added salt. Unexpectedly, the guest loved the “crunch potato slices,” and Crum’s “Saratoga chips” treat soon caught on. They arrived in grocery stores in 1895, offered in barrels or tins. Then, in the 1920s, Laura Scudder was making potato chips at her Monterey Park, Calif., food company. Seeking a way to ensure that her batches lasted longer, she had her workers fashion sealed waxed-paper bags—and in the process changed how goods were sold. Around the same time, Wise Potato Chips in Berwick, Pa., Utz Quality Foods in Hanover, Pa., and Lay’s in Dorset, Ohio, started selling their own versions. Today potato chips are a global business, generating several billions of dollars in annual sales.

Another giant among national snack indulgences is the Hostess Twinkie. In 1930 Jimmy Dewar, the manager of Continental Baking Co. in Chicago, was looking for something to take the place of the firm’s cream-filled strawberry shortcake when the fruit was out of season. “We needed a good two-pack nickel number,” he recalled. Dewar filled some oblong shortcake molds with sponge cake, injected banana filling and dubbed them Twinkies after a nearby billboard for Twinkle Toe Shoes. When bananas became unavailable during World War II, the firm switched to vanilla crème.

Twinkies became a ubiquitous if not-that-healthy pleasure for kids, students and people on the go. They even made their presence known in judicial circles. After Dan White killed San Francisco gay-rights activist and politician Harvey Milk in 1978, White’s outlandish defense that eating junk food had led to his murderous ways was roundly derided as the “Twinkie defense.” Urban myth also has it that the chemical-infused ingredients of what has been called the “cream puff of the proletariat” could survive a nuclear war. Not true—Twinkies have only a 45-day shelf life.

Twinkies briefly bowed out with the 2012 bankruptcy of food maker Hostess. When word spread of the potential demise, Twinkie junkies rushed out to stockpile boxes. Although production stopped in late 2012, new owners purchased the company, and by the middle of 2013, Twinkies were back on shelves across the country.

The Tailgate Party, the Barbecue Grill and the Aluminum Can

There’s something tribalistic about a tailgate party, where hundreds of strangers line up their cars, set up portable grills and pop open a few cold ones. It did in fact take a tribe to lay the ground for the phenomenon—specifically, the pre-Columbian Arawak tribe of Hispaniola, who slow-cooked meat over green wood. The Spanish conquistadors liked the smell and taste of what they called barbakoa and brought the barbecue style of cooking to mainland America. By the 18th century, those in the Southeast were pit-roasting pigs, and as settlers moved west, different methods of barbecuing evolved. The process was made easier in 1897 when Ellsworth Zwoyer formed charcoal briquettes. And even before Henry Ford’s Model T made pulling up to an event easy, tailgating was alive and well. Consider the First Battle of Bull Run, in Prince William County, Virginia, in July 1861. People arrived in stylish carriages and buggies, and women came with carts laden with pies and other foods to sell. “The spectators were all excited,” reported a London Times correspondent of the battle between the South’s Confederates and the North’s Yankees, “and a lady with an opera glass who was near me was quite beside herself when an unusually heavy discharge roused the current of her blood—‘That is splendid. Oh my! Is not that first rate?’ “ The North lost that round but scored the decisive win at Appomattox Court House in Virginia in April 1865.

The first football tailgate is thought to have taken place in November 1869, when Rutgers beat neighboring Princeton. And though small and large grills have long been available, the barbecuing set got a real boost from George Stephen of Weber Brothers Metal Works in Chicago, who in 1952 fashioned a dome-shaped grill, which evenly distributes heat and makes one great burger.

Canned beer had been around since 1935, but seven years after Stephen’s invention, Coors Brewing Company introduced the first aluminum can, and soon other firms also offered these light, simple-to-transport and rustproof containers. Drinking was made quicker by Ermal Fraze, an Ohio tool manufacturer who devised the pull-tab opener. Then came Daniel Cudzik, an engineer with Reynolds Metals in Richmond, Va., who in 1975 created the safer and less polluting stay- tab. As the planets (and cars) aligned, a tailgate gathering became the perfect spot for people to come together to celebrate a game—whether they actually go inside or not.

Meals Made Easy

Not that long ago, making a meal could be a time-consuming process. Many people still had to harvest their own crops and hunt and trap for what they needed before they even entered the kitchen. Three ingenious Americans made food gathering, preparation and eating a lot easier. In Chicago in 1894, Frederick Weeks Wilcox patented a paper “oyster pail” container. Fashioned origami-like from a single piece of paper, it formed a trapezoidal, leakproof, insulated box that vented steam and stayed shut with a simple wire handle. It was used to hold shucked oysters as well as ice cream and other foods. The creation of the box coincided with the rise of Chinese takeout and ensured that your beef and broccoli, Buddha’s Delight and steamed rice not only would arrive hot but could also be neatly stored for late-night noshing.

The arrival of grocery stores and supermarkets made getting basic goods easier. But cooks still had to do the often onerous chore of, you know, cooking. New York–born Clarence Birdseye helped provide an alternative. As a fur trader, he had spent time in Labrador, Canada, where he had learned how Eskimos quickly froze fish for the winter. Unlike the slowly chilled food that Americans had, the natives’ fish tasted good when eaten months later. That’s because quickly frozen food does not develop the large ice crystals that ruin cell membranes and degrade texture and flavor. In 1925, Birdseye developed his “quick freeze machine,” which chilled food to –40° to –45°F and locked in taste, texture and freshness for vegetables, fruits, fish, meat and even oysters. All one then had to do was heat and eat.

During World War II, William Maxson came up with a better way to feed American troops who were being flown to the front. He created the first frozen meals: an entrée and side dishes set on cardboard trays treated with plastic and frozen to a point at which, as The New Yorker commented, “It’s as hard as yesterday’s dinner rolls and in a state to last until Doomsday at a temperature of zero.” At chow time, the on-flight mess staff simply heated the trays in a convection oven called Maxson’s Whirlwind. After the war, commercial flights started serving prepared foods, and it was only a matter of time before TV dinners made it into homes across the land, allowing families to sit and eat as they watched episodes of The Honeymooners, Gunsmoke and Kukla, Fran and Ollie.

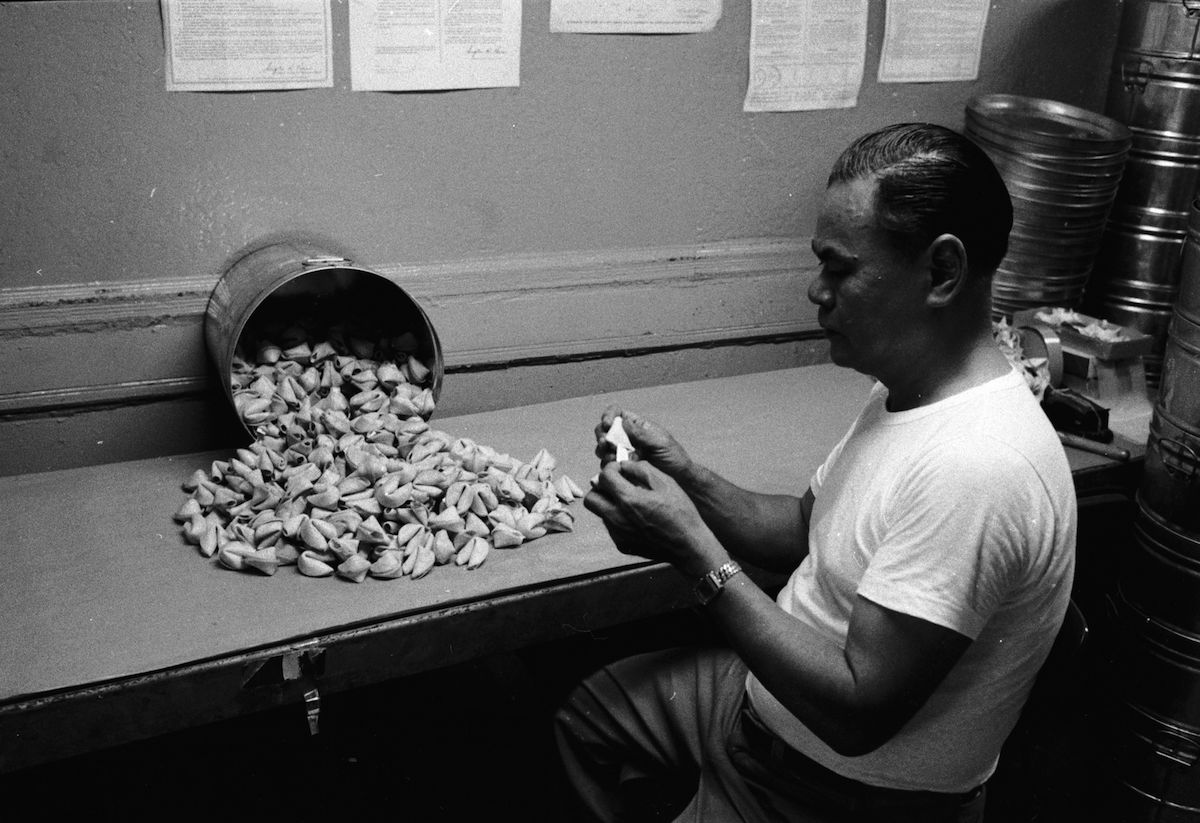

The Fortune Cookie

No one believes that the prediction sometimes offered in a fortune cookie will come true. But that hasn’t stopped those dining in Chinese restaurants (or ordering takeout) from eagerly cracking open the crunchy vanilla-flavored treat at the end of the meal. The cookie, though— like chop suey and General Tso’s chicken—is not straight out of China. It was first baked in a California restaurant at the turn of the 20th century. Its origin, like the haiku brevity of its fortune, is most likely the tsujiura senbei “fortune crackers” offered at bakeries near a Shinto shrine in Kyoto, Japan. Along with a canned proverb and a brief Chinese-language lesson, most fortune cookies now also contain “lucky” lottery numbers. And for some, their cookies really have brought fortune. One Tennessee woman in 2005 brought dinner at her favorite Nashville-area restaurant. Her cookie promised, “All the preparation you’ve done will finally be paying off.” It seemed to bode well, so she bought a Powerball ticket using the numbers included, and she won. She was not the only one to receive that fortune and buy a ticket. An unprecedented 110 people split the second prize for the $19.4 million jackpot drawing, each taking home $100,000 to $500,000. When officials looked into the suspiciously high number of winners, they discovered that many of them had played the cookie-sent numbers, which originated at Wonton Food, a bakery in Queens, N.Y. As one of that company’s sales executives said, “Those people are very, very lucky.”

The Coca-Cola Bottle

In 1886, Atlanta pharmacist John Pemberton concocted a flavored syrup that, when mixed with carbonated soda, made a refreshing, fizzy drink. Asa Candler bought his formula in 1888, but at the time, five-cent glasses of Coca-Cola could be enjoyed only at soda fountains. A few years later, Joseph Whitehead, Benjamin Thomas and John Lupton acquired the bottling rights and filled straight-sided bottles with the stuff. But success breeds imitation, and competitors with suspiciously similar products, such as Toka-Cola and Koka-Nola, replete with knockoff logos, marketed their beverages. Needing to set its drink apart, the Coca-Cola Bottling Association asked its numerous glass companies to create a unique bottle. The Root Glass Company in Terre Haute, Ind., proposed an easy-to-grasp bottle based on the elongated shape of a cocoa bean, complete with the seed’s rippling ribs. The company patented the design and decided to have it colored what became known as “Georgia green” in homage to its home state. The bottle came out in 1916 and was an immediate hit, with six-packs appearing in 1923. It has such a distinctive shape—one that could even be recognized by touch in the dark— that after its patent expired in 1977, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office issued the company a rare trademark registration for its package. The famed industrial designer Raymond Loewy crowed that the bottle was the “perfect liquid wrapper,” and such artists as Salvador Dalí, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol have celebrated it in their art. Its fame has lasted longer than a Warholian 15 minutes: although the drink is now available in cans and containers of various shapes and sizes, many of the 1.9 billion servings sold each day are still quaffed from the traditional bottle formed a century ago.

K-Rations

OK, it wasn’t your mother’s home cooking. But at least your folks knew that while you were fighting in World War II, the Army quartermaster gave you three squares a day. And though pre-packaged meals existed before the war, the Army, aware that soldiers hated them, sought to improve the fare for the troops. So the service asked physiologist Ancel Benjamin Keys to create a lightweight yet nutritious meal that could be carried by bailing paratroopers. What he put together was the K-ration. It came in a wax-coated cardboard box with three separate meals of concentrated or dehydrated food, cereal, crackers, bouillon powder, potted meat and the ever popular Beech-Nut chewing gum and Chesterfield cigarettes. The food weighed just 28 ounces but was packed with some 3,000 calories. And even if Mom would have made something a lot tastier, K-rations worked well for the millions off at war. The gum was especially loved by the children of the liberated lands, who followed troops with the hope of being handed a treat. By the end of the war, the U.S. Army had distributed 105 million K-rations.

The Drive-Through Window

On-the-go food places have existed since the 1920s, but it took car culture to really get the phenomenon rolling. By World War II, carhop service was common at drive-up restaurants offering fare such as burgers and ice cream loats, some brought out by roller-skating waitresses. In 1947, Red’s Giant Hamburg in Springfield, Mo., opened the first drive- through. No longer did time-obsessed diners need to walk into a restaurant or pull up and wait to be served. The idea exploded, with customers gliding into designated lanes, choosing their selections from a large placard, placing their order by speaking into a two-way speaker and then picking up their bagged meal; In-N-Out Burger also gave customers a sheet of butcher paper to protect their laps while they ate. By the 1980s, fast-food chains reported that 50% of their business came through the windows. Some companies devised products that could be held in one hand while the other clutched the wheel.

But it isn’t just food that people like to pick up without leaving their cars. There are now drive- through banks, pharmacies, liquor stores and bars (maybe not a good idea), voting booths, law firms and emergency rooms. There are wedding chapels for tying the knot on the go—and even funeral parlors, where the bereaved can view their departed loved ones, thus making us all the more rushed in love and death.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com