There’s no longer doubt that Zika causes birth defects like microcephaly and other severe brain abnormalities, United States health officials announced on Wednesday.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that after a comprehensive review of research, the agency can confidently say that the virus causes certain birth defects. Until now, the CDC had said that evidence strongly supports a link, but that the link was not definitive. The agency published its review in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This is a study that marks a turning point in the outbreak. It is now clear, the CDC has concluded, that Zika does cause microcephaly,” said CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden during a call with reporters. “There is still a lot that we don’t know, but there’s no longer any doubt.”

The CDC says there’s no single piece of evidence that proves the link, but that by reviewing many studies and implementing criteria used to determine a link between an environmental exposure and birth defect, the agency is now certain. “This is an unprecedented association. Never before in history has there been a situation where a bite from a mosquito could result in a devastating malformation,” said Frieden. “The science now shows what the hundreds of impacted families have suspected all along.”

The researchers used two different standard criteria methods that are meant to determine whether a pathogen or other element causes birth defects. One of the methods required the researchers to take the available evidence on Zika and determine whether the exposure occurs at a critical time during pregnancy, whether there’s a specific pattern of defects, if the link involves a rare exposure and a rare defect, and if the link makes biological sense. The researchers felt that the available evidence lined up with the criteria to prove the causal link. Many of the women infected with Zika who have babies with microcephaly report infections in the first trimester or early second trimester, and the virus has been observed in the brains of babies with severe microcephaly who have died.

“Now that we’ve confirmed the causal relationship between Zika and birth defects, we can use this information to redouble our efforts to prevent Zika, more narrowly focus our research and communicate even more directly about the risks of Zika,” says Dr. Sonja Rasmussen, lead author of the study and director of the division of public health information and dissemination at the CDC. “This doesn’t mean we have all the answers. All the evidence supports a causal link, but many questions remain.”

For instance, it’s still not known why some pregnant women who get Zika do not have babies with microcephaly. Since not all people who contract Zika present symptoms, scientists want to know whether experiencing symptoms contributes to birth defect risk. There’s also the possibility that other factors beyond Zika, like prior infections, contribute to an increased risk for birth defects. The CDC says brain defects may be just one disorder in a range of health problems caused by the virus. “We still need many more answers, some of which could take years,” said Frieden.

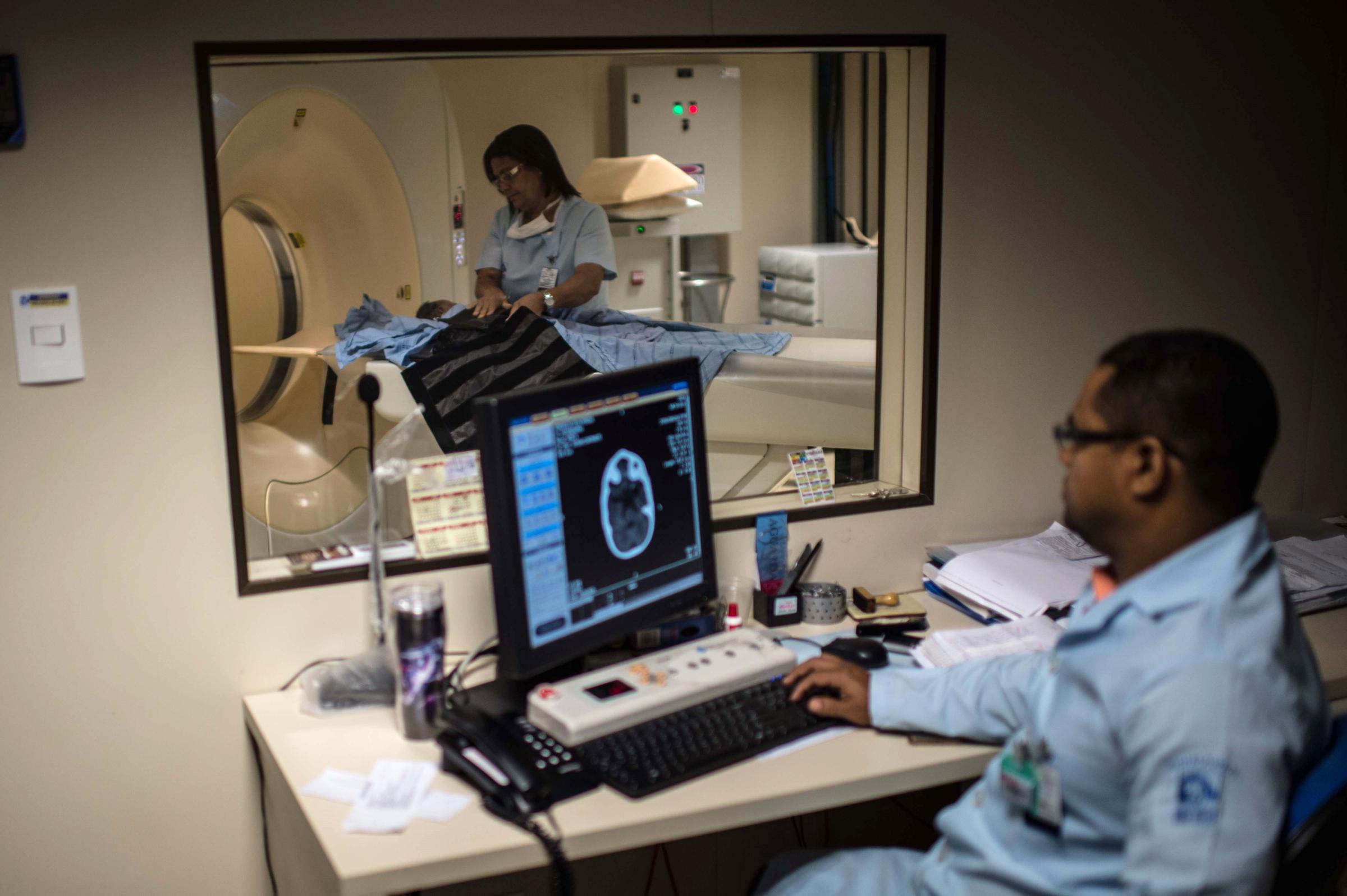

See the Impact of Zika in Brazil

The CDC came to this conclusion now, Rasmussen said, because, “we wanted to do this in a very careful and systematic way. We didn’t want to say that Zika virus causes birth defects before we were really confident that was the case.”

The CDC says it is not changing any of its current guidance and recommendations for protection from Zika. The agency still maintains that pregnant women should avoid travel, and that women and their partners in places with active Zika infections should take measures to avoid sexual transmission of the virus.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com