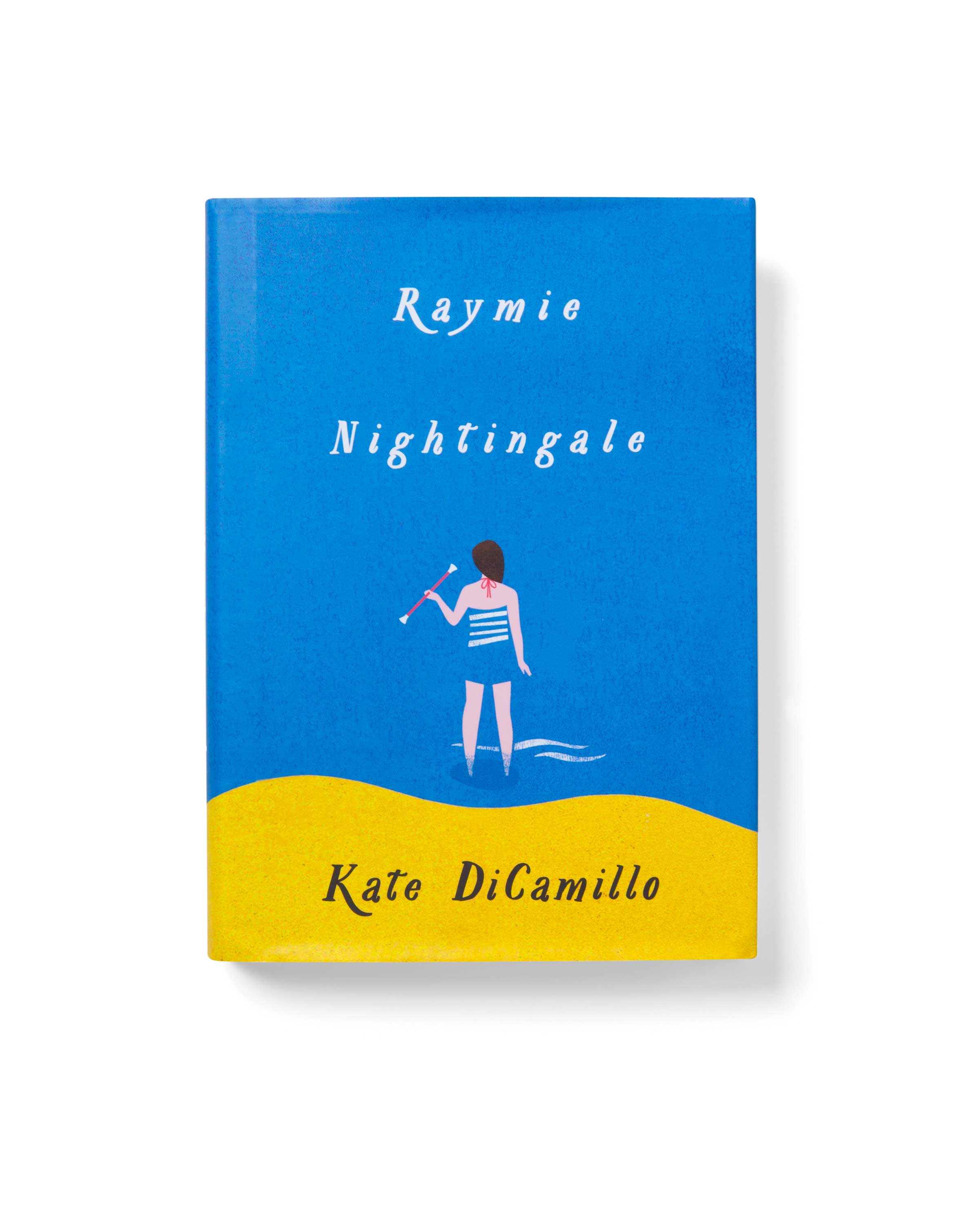

When tragedy happens, some people wallow. Others make plans. Ten-year-old Raymie Clarke falls in the latter category, so after her father runs off with a dental hygienist, she plots a solution: win the 1975 Little Miss Central Florida Tire contest, get her picture in the paper and bring him back. To do all that, she must learn how to twirl a baton.

Kate DiCamillo has made a career of inventing young characters whose soulfulness rivals that of the adults in their lives, from her iconic first novel for young readers, Because of Winn-Dixie (2000), to the Newbery-winning Flora & Ulysses (2013). Raymie Nightingale too reminds adults about the profound depth of childhood feelings. As with Katherine Paterson’s Bridge to Terabithia or Wilson Rawls’ Where the Red Fern Grows, some readers may require tissues.

Raymie’s classmates in baton-twirling lessons are Beverly Tapinski, whose father is also MIA and whose mother leaves bruises on her face, and Louisiana Elefante, an orphan whose grandmother can only afford to feed her canned tuna fish. Beverly has little use for the Little Miss Central Florida Tire competition–in fact, she’d like to sabotage it–but Louisiana wants to take home the crown and the $1,975 that comes with it. Together with Raymie, they become the Three Rancheros, stumbling into mischief around town and beginning to see past their own problems.

On top of her father’s desertion, Raymie struggles with the death of her kind, elderly next-door neighbor. In the wake of Mrs. Borkowski’s passing, feeling misunderstood in her grief, Raymie has a poignant realization: “It occurred to her that nobody really knew what anybody else was upset about, and that seemed like a terrible thing.” These interpersonal troubles, and the effort we all make to connect, are the heart of the novel. As Raymie grows into a kind of young Florence Nightingale (hence the nickname in the title) she learns that helping others can be a way to help herself.

DiCamillo, who has just ended her tenure as the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, understands that children can handle the tough stuff in fiction–after all, they have to handle problems like divorce, grief, abuse and poverty in real life. And a book like this can help. As Raymie’s neighbor told her before dying, “If you were in a hole that was deep enough and if it was daylight and you looked up at the sky from the very deep hole, you could see stars even though it was the middle of the day.” For children looking up from their own deep holes, the Three Rancheros could be those stars.

–SARAH BEGLEY

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com