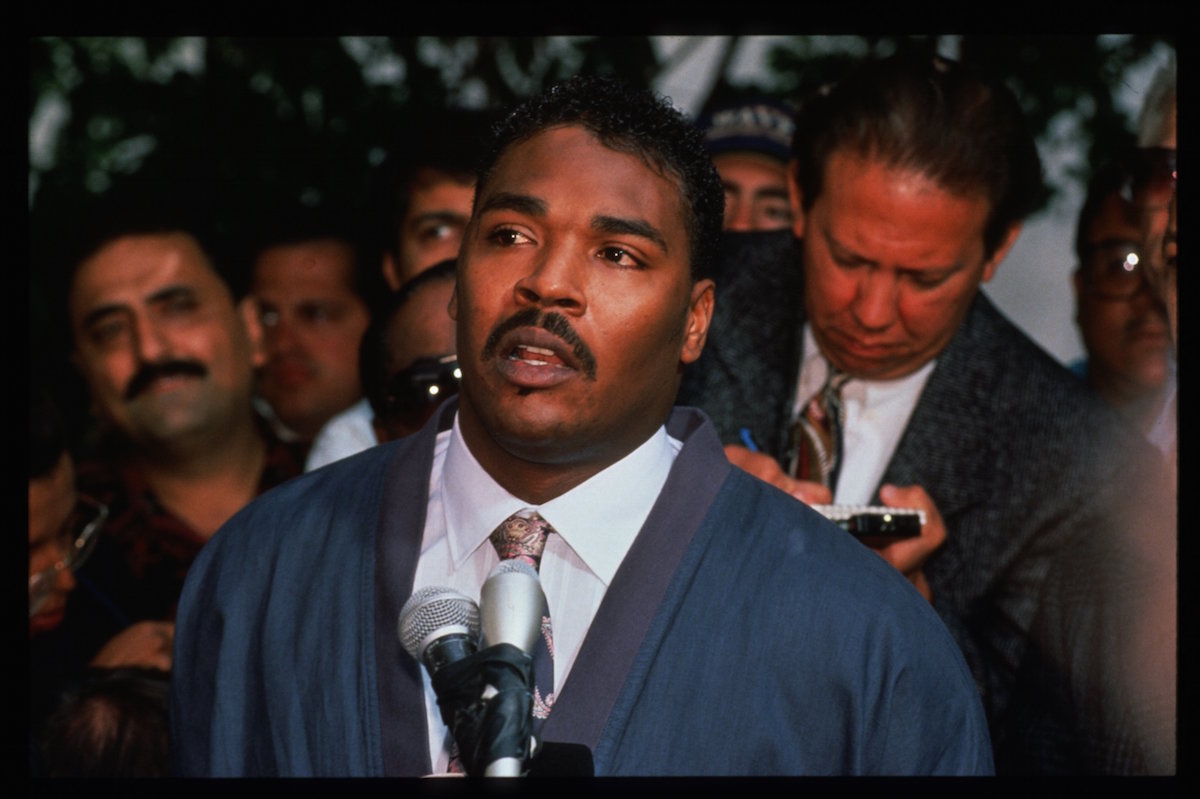

When Rodney King died in 2012—almost exactly two decades after his 1992 beating became the most famous example of police brutality caught on video—the writer Touré noted in TIME that what happened at the hands of Los Angeles cops did not make King special. “What separated [the incident] from others was that 81 seconds of it was surreptitiously videotaped by a stranger, giving the world a look at the police coldly and cruelly beating a black man,” he wrote.

That difference, the infamous tape, has placed Rodney King at the start of a continuum that stretches ever on, as citizen-filmed footage and police-worn body cameras and dash-cams reshape our understanding of the relationship between law enforcement and the public they’re sworn to protect. The camcorder footage of King’s savage beating did mark a critical moment in America’s long and tangled racial history, but it was not the first incident of police misconduct to be caught on camera.

Home movies had been around for decades by the time King had his run-in with the police, and Americans had gotten used to filming all kinds of moments from daily life. In the early years, however, those cameras were clunky, only able to capture short, soundless clips. That changed by the late 1970s with the advent of video tape recorders and then easy-to-use 8-mm camcorders. By 1991, plenty of people had and used video cameras. While most used them to chronicle birthday parties and days at the beach, they were also used to capture some galling examples of police misconduct. When the news of King’s beating broke, TIME rounded up just a few examples of “America’s ugliest home videos,” including:

Laguna Beach, Calif. A neighbor across the street from an unruly party on June 17, 1990, recorded a harrowing 90 seconds of violence. Although a car partly blocked the view, an officer can be seen on camera swinging his leg in a kick at Kevin Dunbar, 24, a homeless man, while a number of other officers held him after he refused to obey an order to get down on the ground. The man, his face bleeding, was then lifted to his feet and led away to a squad car. A lawsuit against the Laguna Beach police department was filed last month, and the tapes are expected to be important evidence.

Chicago. Max’s Italian Beef Restaurant on the northwest side had a security camera in full view, but the two uniformed police rifling the cash register and prying open the safe last July were too busy to notice. The veteran officers allegedly lifted $7,000. They were indicted and await trial.

Los Angeles. On Aug. 30, 1989, a seven-man narcotics squad from the county sheriff’s department was investigating a money-laundering scheme. When the suspects left behind $498,000 in cash, the plainclothesmen skimmed $48,000 in booty. The ”money launderers” turned out to be FBI agents, and their hidden cameras were rolling. Charges of conspiracy, theft and tax evasion were brought against the seven for that and other skimming operations. They received prison sentences last week of two to five years.

New York City. Police were trying to enforce an unpopular curfew on Manhattan’s Tompkins Square Park, and hundreds of protesters had gathered on Aug. 6, 1988. Without warning, a wave of cops tore into the crowd and began clubbing and kicking demonstrators and bystanders alike. A video artist taped scenes that became key evidence in a trial of five officers. Though none were convicted, the top cop at the park that evening retired, and the police commissioner publicly criticized the actions of New York’s finest as leading to unnecessary confrontations.

Those four examples, however, would prove to be only half parallel with the King case. Despite the video footage, which had been captured by a man named George Holliday, a criminal jury did not find the four officers who were tried in the case to be guilty. The footage did, however, help puncture the idea that such events almost never occurred, as one TIME reader wrote in a letter in April of 1991. “How could the beating of Rodney King be an isolated event?” asked Rob Adelman of Westminster, Calif. “The odds against capturing it on videotape are enormous unless such occurrences are more common than we thought. And why did nobody ever hear racist communications between police officers before? Could it be that someone was listening and didn’t care?”

Read TIME’s first report on Rodney King, here in the TIME Vault: Police Brutality!

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com