By Josh Sanburn

amsey Orta’s footage of Eric Garner’s final moments—a seemingly routine confrontation with police that in a flash turned deadly–ricocheted around the world, turning a local tragedy into a seminal moment in what became the Black Lives Matter movement. But Orta has virtually nothing to do with the protests and social justice organizations that have sprung up since. And today, one year after Garner’s death on July 17, 2014, he occasionally wishes he hadn’t been a part of it all.

amsey Orta’s footage of Eric Garner’s final moments—a seemingly routine confrontation with police that in a flash turned deadly–ricocheted around the world, turning a local tragedy into a seminal moment in what became the Black Lives Matter movement. But Orta has virtually nothing to do with the protests and social justice organizations that have sprung up since. And today, one year after Garner’s death on July 17, 2014, he occasionally wishes he hadn’t been a part of it all.

“Sometimes I regret just not minding my business,” Orta tells TIME. “Because it just put me in a messed-up predicament.”

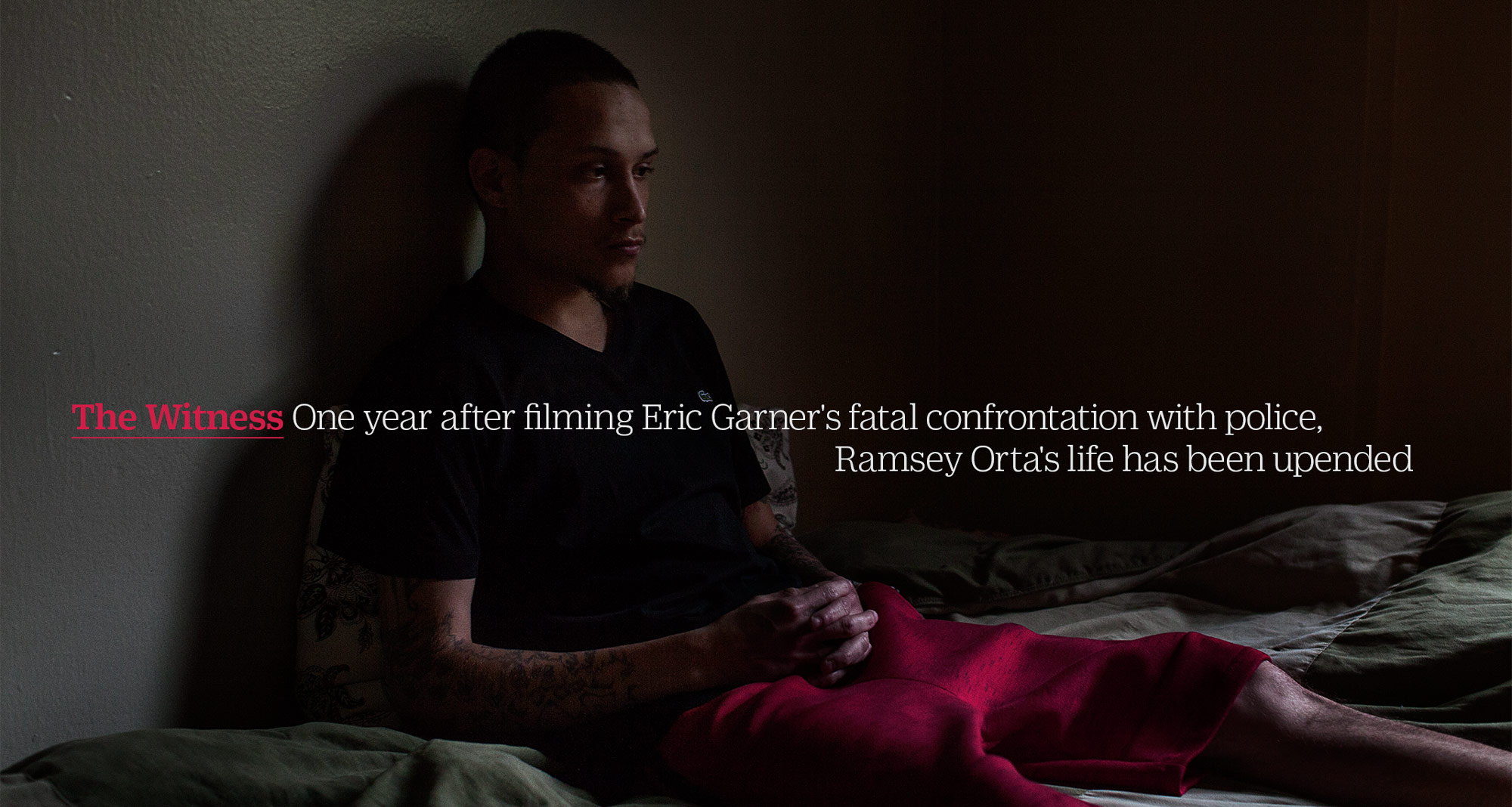

Orta no longer resides in Staten Island. Instead, he lives in a small, narrow apartment with his mother and brother in the New York City area and has asked that more detailed information about the location not be published because of what he claims is a pattern of harassment by police since the Garner video was published. The doorknob on the building’s main entrance is broken. Its halls smell of urine. Inside, Orta sleeps on a mattress on the floor. When he’s not in court fighting a series of drugs and weapons charges, Orta’s usually here, watching TV or on his phone. Sometimes he pays attention to the latest high-profile incident involving police and unarmed black men. Sometimes he tunes them out.

It’s likely that no one outside of Staten Island would ever know the name of Eric Garner without Orta’s video, which became the first in a wave of recordings of African-Americans in violent confrontations with white police officers to command national attention. A month later came Ferguson and Michael Brown, then Cleveland and Tamir Rice, Baltimore and Freddie Gray, North Charleston and Walter Scott, McKinney, Texas, and the pool party. At least a dozen incidents, some recorded, some not, have made national headlines since Garner’s death. And the phrase “I can’t breathe,” which Garner can be heard repeating in Orta’s video as police held him down, has been adopted as a primary rallying cry of the movement.

But a year later, Orta says he would at the very least rethink his decision to pull out his camera. In two separate interviews with TIME, Orta expressed ambivalence and even outright regret over getting involved. And if he had to do it over again, he says he would release the video anonymously.

Video by Salima Koroma for TIME

n the last year, Orta’s life has been upended. He has been arrested three times since August 2014. The first, for criminal possession of a handgun he allegedly tried to give a 17-year-old, came a day after Garner’s death was ruled a homicide by the city’s medical examiner. In February, he was arrested again on multiple charges of selling and possessing drugs. The third came on June 30 when he was accused of selling MDMA to an undercover cop. A lab test later showed that the alleged MDMA was fake and the charges were reduced. All told, Orta is facing more than 60 years in prison if convicted on all charges.

n the last year, Orta’s life has been upended. He has been arrested three times since August 2014. The first, for criminal possession of a handgun he allegedly tried to give a 17-year-old, came a day after Garner’s death was ruled a homicide by the city’s medical examiner. In February, he was arrested again on multiple charges of selling and possessing drugs. The third came on June 30 when he was accused of selling MDMA to an undercover cop. A lab test later showed that the alleged MDMA was fake and the charges were reduced. All told, Orta is facing more than 60 years in prison if convicted on all charges.

Orta, 23, is shy and speaks in a soft almost-mumble. He would be unassuming if not for his steady gaze, which makes you think he’s going to say more, though he rarely does. And he is tiny. Arrest records list him at 5’6” and 115 lbs., but that might be generous.

Orta was born in Manhattan and lived there until he was about 10 years old. Around age 12, his parents split up and he soon found himself helping raise his younger brother Jaime.

“He grew up fast,” says Emily Mercado, Orta’s mother. “He was like my little husband, telling me what to do, where I’m going.”

The family bounced around from New Jersey to Pennsylvania and then back to New York, relocating to Staten Island around the end of 2009. Back in New York, Orta says he worked mostly in delis stocking shelves and making sandwiches. Orta didn’t finish high school but later attended trade schools and studied carpentry.

He also had multiple run-ins with the law. Since 2009, Orta has reportedly been arrested dozens of times. In August, an unnamed police source told the Staten Island Advance that Orta had been arrested 26 times, with at least 10 of those cases sealed by the courts. His lawyers say his number of total arrests is far fewer.

Orta was convicted for attempted sale of a controlled substance in 2011 and criminal possession of stolen property in 2012. For those, he served six months in jail. According to the Staten Island district attorney’s office, Orta has also been convicted of six misdemeanors.

Orta became acquainted with Garner soon after moving to Staten Island. They first met near where Garner died, outside a beauty supply store in the Tompkinsville neighborhood. Orta describes Garner as an amiable guy, often laughing and cracking jokes. The day Garner died, Orta says he and Garner were making plans to get food when police approached.

“I was already on my phone,” Orta says. “I always seen them cops doing something to somebody else, so I figured I’d just record it.”

Garner was known to the local cops and had reportedly been arrested more than 30 times since 1980. On the video, he can be seen pleading with officers, claiming he wasn’t doing anything wrong and accusing police of unfairly harassing him. Daniel Pantaleo and several other officers tried to detain Garner, who resisted arrest and was wrestled to the ground. Garner became unresponsive and later pronounced dead at a hospital. Two days later, Pantaleo was stripped of his gun and badge and, along with another officer involved, placed on desk duty. In December, a grand jury decided not to indict Pantaleo in Garner’s death. On July 13, New York City agreed to a $5.9 million settlement with Eric Garner’s estate for damages related to his death.

Orta released the video to the New York Daily News the day after Garner’s death. Since then, Orta says that police have harassed him and his family. In the weeks after Garner’s death, he released two videos on YouTube in which he claims he was unfairly targeted by police. He says he was stopped twice for robberies in which he had no involvement and claims that police shone lights in the windows of his Staten Island home.

On Feb. 10, Orta, his mother, and brother, Michael Batista, were arrested on multiple drug charges after police entered their home in the early morning hours. All three were charged with multiple felony and misdemeanor drug counts. Those cases are still pending. Orta’s mother says she’s been in therapy since the incident for what she describes as post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I don’t want to be around cops,” Emily Mercado says. “I stay indoors.”

Orta’s aunt, Lisa Mercado, who has often spoken on behalf of the family, says she too has been followed by the police and claims that Orta’s possessions were taken from his former Staten Island home after he moved. She says the family filed a police report but the cops never investigated.

“Only Ramsey’s stuff was missing,” she says.

From February to April, Orta was locked up in Rikers Island, New York City’s largest jail, awaiting bail following his arrest on drug charges.

Orta’s lengthy arrest record, however, which includes numerous charges from before the Garner incident, makes it difficult to back up many of his claims about police retaliation. The NYPD did not respond to multiple requests to comment for this story.

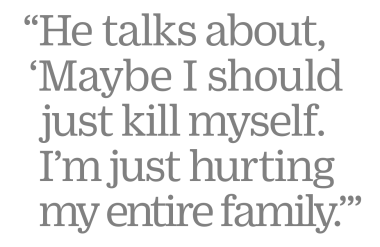

What is clear is that the attention from the Garner video has changed Orta, family members say. “He walks around with fear,” Lisa Mercado says. “He was always an outspoken person. He’s not anymore. He talks about, ‘Maybe I should just kill myself. I’m just hurting my entire family.’ He said he knew he was doing the right thing, but it turned out to be hell. It messed us all up.”

Feidin Santana, a witness to the shooting of Walter Scott by Officer Michael Slager in North Charleston, S.C.

Photograph by Sean Rayford for TIME

rta isn’t the only witness to a fatal police encounter whose life was changed after pulling out a smartphone. On April 11, Feidin Santana was walking to work in North Charleston, S.C., when he saw Walter Scott, a black man, fleeing from Michael Slager, a white police officer. Santana hit record on his phone as Slager fired eight shots at Scott’s back. The officer wasn’t initially charged, but after Santana’s video was released, Slager was fired and indicted for murder.

rta isn’t the only witness to a fatal police encounter whose life was changed after pulling out a smartphone. On April 11, Feidin Santana was walking to work in North Charleston, S.C., when he saw Walter Scott, a black man, fleeing from Michael Slager, a white police officer. Santana hit record on his phone as Slager fired eight shots at Scott’s back. The officer wasn’t initially charged, but after Santana’s video was released, Slager was fired and indicted for murder.

In an interview with TIME, Santana says he has since moved out of North Charleston and no longer feels safe walking to the barbershop where he works.

“I used to leave the barbershop at 10, 11 o’clock at night and go safely to my house,” Santana says. “Now, it’s not the same. I don’t feel that I should be doing that anymore.”

Santana says he waited two days before handing the video over to Scott’s family, saying he even considered leaving North Charleston before making it public.

“One of my concerns before giving the video to the family was retaliation from the police department,” he says.

But after Santana saw what he considered inaccurate reports about the shooting, he decided to publicize the recording. Today, Santana says he tries to keep out of situations that could get him in trouble with the law.

“Right now, I’m the only witness besides the ex-officer,” Santana says. “If it comes to a trial, it depends on me.”

There have been several other instances of bystanders recording police encounters since Garner, including the arrest of 25-year-old Freddie Gray recorded by Baltimore resident Kevin Moore in April. Gray later died from a severe spinal injury while in police custody, which set off violent protests and led to the indictment of six officers involved in detaining Gray. In early June, 15-year-old Brandon Brooks recorded Eric Casebolt, a police officer in McKinney, Tex., pulling his gun at a pool party, detaining an unarmed black teenager wearing a bathing suit, and pinning her to the ground.

Orta has followed some those incidents. But he says he’s far more concerned with his own life.

“I got a lot more to deal with than worry about somebody else’s situation,” he says.

Since he left Staten Island, Orta’s life has taken on shades of normalcy. He says he’s able to get out, go to the movies, stop by the grocery store. His mother says the cops in their new neighborhood don’t recognize them, so they don’t feel followed.

Orta’s old life, however, may never return. He is currently facing charges of assault and harassment, robbery, criminal possession of a weapon, petty larceny, sale of an imitation controlled substance, and criminal possession of stolen property, among other lesser offenses. If convicted of all charges, he could be in prison until his 80s.

—With reporting by Paul Moakley

Design by Alexander Ho