Presidential campaigns feel more like sporting events than democracy. The candidates pretend they want voters to think and choose by putting forward policies and debating. But stump speeches and motivational slogans often feel like a never-ending commercial aimed at getting us to buy something we don’t really need.

The media covers it like entertainment. You can hear pundits rattling off positions as the horses round the bend: “They are running neck and neck” or “so-and-so is pulling away from the pack.”

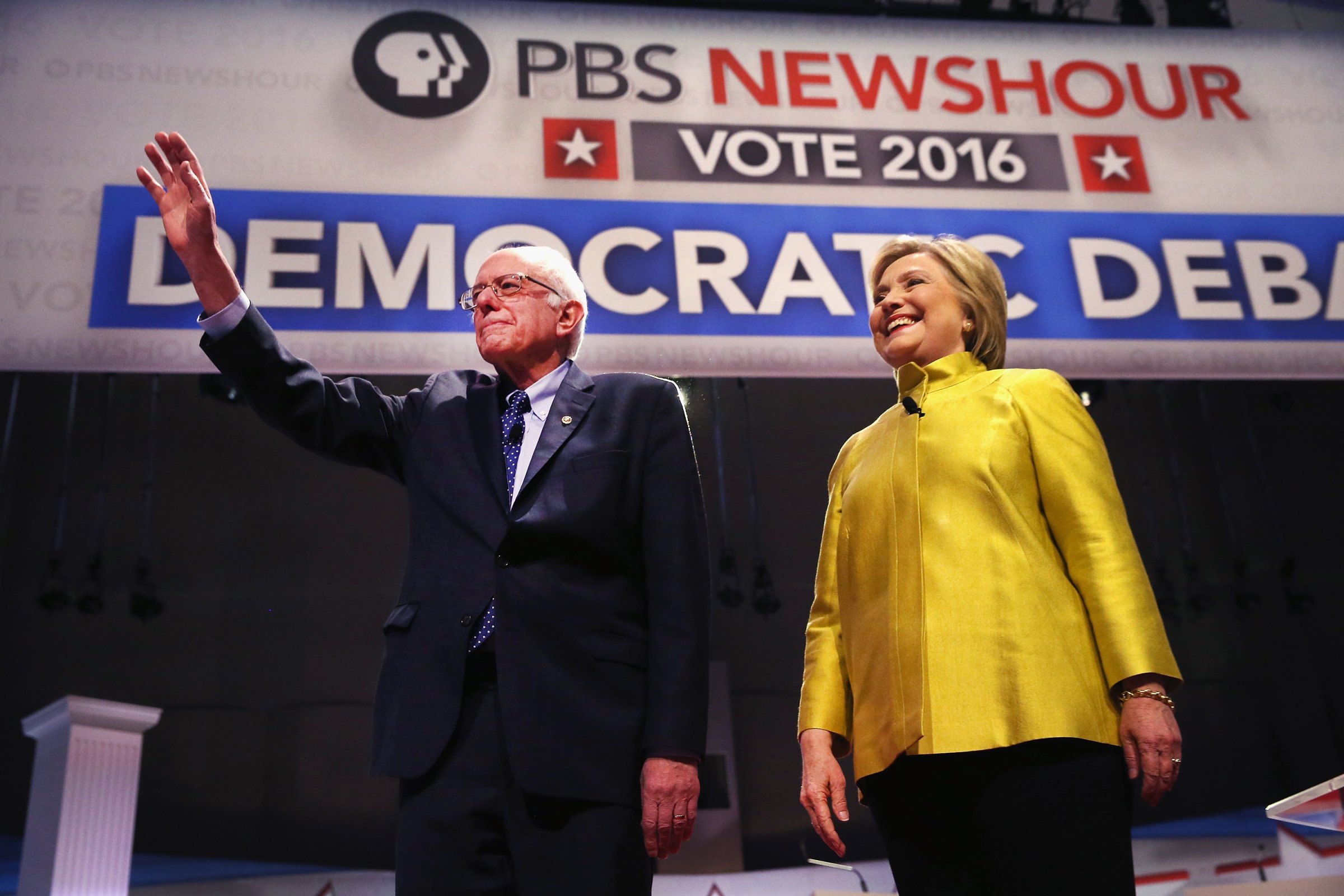

But if there’s one feature of the whole circus that sets my teeth on edge, it is the attack on our imaginations. This has been particularly the case this election season—and particularly from the Democratic side. You don’t have to be a supporter of Senator Bernie Sanders to see the relentless assault on the “political revolution” he commends.

Words like naïve and idealistic, and, often enough, unrealistic. Questions like “How will he implement it?” Concerns about “How much will it cost?” Language like that effectively shuts down any serious consideration of his proposals and candidacy. We are urged instead to stick with the familiar. Hillary Clinton knows how to play the game. She can actually win a general election, they say.

Even when serious people are critical of Secretary Clinton, one gets the sense that we can’t imagine otherwise. Ta-Nehisi Coates rightfully took Clinton to task over her comments about Reconstruction just as he did Sanders over the issue of reparations. But, in the end, he finds himself stuck:

“In the Democratic Party, there is, on the one hand, a candidate who seems comfortable doling out the kind of myths that undergirded racist violence. And on the other is a candidate who seems uncomfortable asking whether the history of racist violence…is worthy of confrontation. …This is not a brief for staying home, because such a thing doesn’t actually exist. In the American system of government, refusing to vote for the less-than-ideal is a vote for something much worse…You can choose in full awareness of the insufficiency of your options….”

What we are left with, while holding our noses, are the choices right in front of us. Nothing else, it seems, is imaginable.

We must resist this conclusion, because it secures the status quo and ensures that the most vulnerable among us will remain vulnerable. But the imagination constitutes the most important battleground in this election.

Read next: Why black voters should write-in “None of the above” on ballots

We have to see beyond what is right in front of us. Doing so doesn’t mean that we ignore the practical question of how will we actually change our politics. That requires an honest assessment—not wild promises—of the political terrain in the United States and full acknowledgment that no one politician can change it all. But asking “how” with a sense of resignation and defeat cannot trump what we imagine is possible. If it does, we’re stuck in quicksand.

In every moment of radical democratic awakening in this country, the imagination has served as the spur. Ordinary people, for whatever reason, decide to risk it all for an idea that the world, their world, could be a different and better place. They imagine what that world might look like and they fight for it. Abolitionists, black and white, did so in the fight against slavery. Figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and Eugene Debs, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Florence Kelley organized with other like-minded people in the early 20th century to put forward a radical democratic vision of the country. They boldly imagined the United States as a just society even though the evidence suggested otherwise. They challenged the view that money mattered more than people and that white people mattered above all.

Imagination, in this instance, isn’t the stuff of fantasy. It’s much more substantive and powerful. In fact, imagination is the key to a robust sense of the good life. It motivates us to act for what is possible and not settle for things as they are, and helps us see the fullness of the humanity of those with whom we live.

Bob Moses, the extraordinary SNCC activist and founder of the Algebra Project, once told me a story about Fannie Lou Hamer. He said that several black sharecroppers were on their way to register to vote in a rural town in Mississippi. They knew what awaited them: that the sheriff could put them in jail or a mob would threaten their lives. As they sat nervously on the bus, a voice kept singing spirituals. Bob said, “She must have sang every song she knew.” Then he realized what she was doing. People were afraid and Ms. Hamer sang to fortify their spirits. In that moment, she was not the icon we now know. She was a black woman sharecropper, invisible for most of her life to the powers that be, willing to risk everything for a way of life that nothing in her previous experience suggested was possible. But she imagined differently and was ready to die for it.

In so many ways, we find ourselves today experiencing a crisis of imagination. The crisis has been in the making for sometime now. One can trace it to the backlash against the political revolutions of the 1960s and the economic order that emerged in its wake. Demands for stability and order trumped commitments to justice. And the idea of freedom morphed into crass calls to freely consume.

We believe that we must settle for the familiar. We believe that our dreams can extend no further than the latest poll. The so-called wisdom of politics has narrowed our visions and has nearly destroyed our political courage. Thinking boldly and dreaming big seems more like science fiction than the source of democracy’s greatness.

But the lack of imagination is something more than a failure to be creative. Percy Bysshe Shelley, one of the great English romantic poets, wrote in A Defence of Poetry, “A man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensely and comprehensively; he must put himself in the place of another and of many others…The great instrument of moral good is the imagination.”

The imagination helps us break loose from the inertia of our habits. It aides us, in those moments when the conservative pull of the past and present bind us to the status quo in all of its ugliness; it helps us break loose from the routine of our daily living and to reject the value of stability and order for something much more dynamic and unformed. The people on that bus in Mississippi felt the power of the imagination in Ms. Hamer’s voice and were able to see possibility in the darkness of a racist southern town.

But this election season our imaginations are under attack—particularly when politicians and pundits talk to black voters. Campaigns have turned their attention to the south and there black voters play an important role. So we hear pundits talk of Clinton’s “firewall” of black voters or Sanders’s failure to attract black supporters.

Members of the black political class emerge as the leaders of the herd, urging black voters to support Clinton no matter her politics or her past. Civil Rights icon, John Lewis, declares his allegiance to Clinton and questions Bernie Sanders’s civil rights credentials. “I never saw him. I never met him…. But I met Hillary Clinton.” Representative James Clyburn of South Carolina dismisses Sanders’s idea of free college education. “I do not believe there are any free lunches, and certainly there’s not going to be any free education… Not in my lifetime, and not in my children’s lifetime.” In other words, Sanders is selling pipe dreams.

In one sense, this is just bare-knuckled politics, and Sanders is taking his lumps. But in a different light something more insidious is happening. To imagine that we could live differently in this country—where greed and selfishness are no longer the order of the day—is said to be a pipe dream. The idea of free education, healthcare as a right for all Americans, a living wage so people can put food on their tables and keep a roof over their heads, and a country where the balance of power shifts from the billionaire class to the hands of hard working people—all of this is a pipe dream?

The political revolution isn’t ultimately about electing Bernie Sanders. It is about an opportunity to change the center of moral gravity in this country. Those content with the status quo are doing everything in their power to keep us from imagining otherwise. The cruel irony is that some black folk are willing accomplices in that work.

There is another feature of imagination worth mentioning here: as Shelley said, it enables us to put ourselves in the place of others. We learn to empathize with those who differ from us. Imagination, in this sense, is critical to our moral judgment.

When our imaginations are arrested, cruelty and mean-spiritedness often rules the day, and the most vulnerable bear the brunt of the nastiness that follows. There is an intimate relationship between the assault on the imagination in the Democratic primary and the ugliness of Trump rallies and the meanness of the Republican primary. They are two sides of the same coin. On the one hand, we can’t envision anything beyond our current arrangements. And, on the other, we fail to see the humanity of others among us. The terror caused by this inhumanity does even more damage to our imaginations. Defeating Trump takes precedence over imagining a better democracy.

Those of us who come out of the tradition that produced Fannie Lou Hamer— the one that produced those who could find hope in places where it seemed that hope had died and who could muster up the spiritual maturity to love people who despised them—must resist those voices who urge us to settle for the world as it is. Ours is an opportunity to shift the very ground of this society. Imagine that. It is a radical idea that scares the hell out of the powers that be. And it should.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com