The announcement on Thursday that President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama plan to visit Cuba in March is notable on its own, coming as part of the President’s ongoing efforts to normalize relations with the nearby island nation. The visit is “another demonstration of the President’s commitment to chart a new course for U.S.-Cuban relations and connect U.S. and Cuban citizens through expanded travel, commerce, and access to information,” the White House said in a statement, noting that it has been nearly nine decades since a sitting president made such a trip.

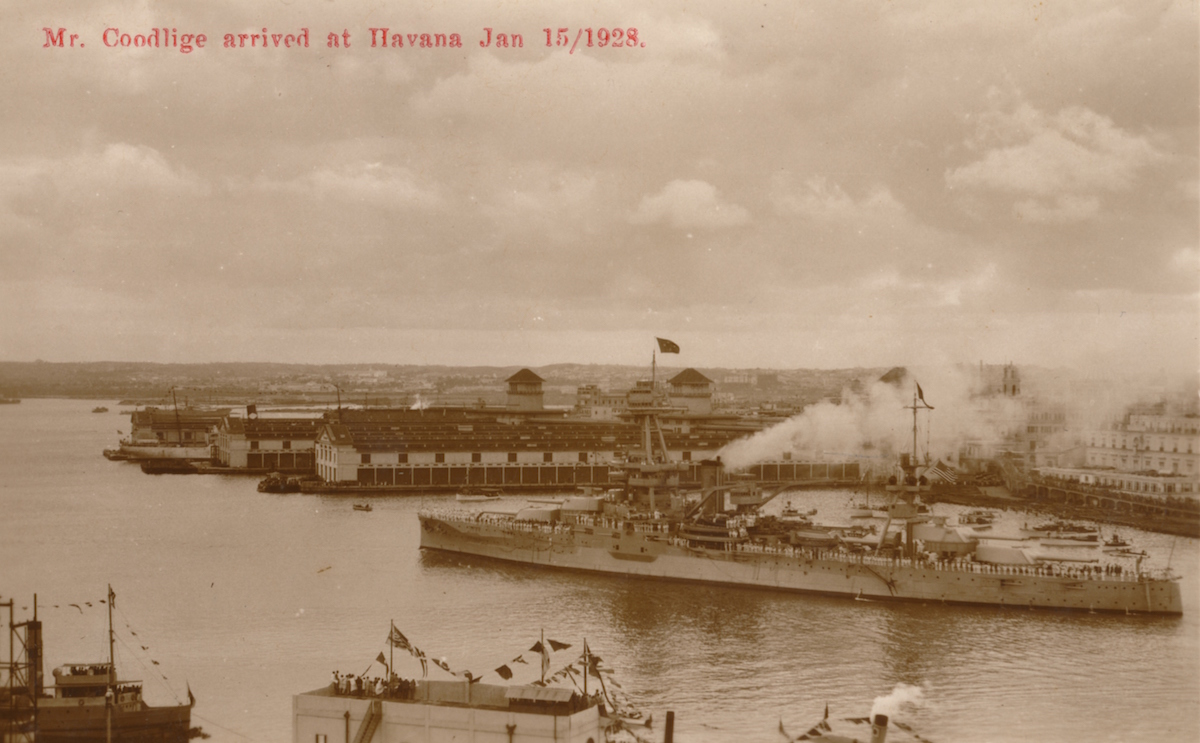

In fact, the 1928 visit in question, made by President Calvin Coolidge in January of that year, was the only time a sitting president has gone to Cuba.

Read More: Why Did the U.S. and Cuba Sever Diplomatic Ties in the First Place?

The limited number of presidential trips to Cuba is surprising not only because of the proximity of the two nations. Until relations soured in the 1950s, the U.S. and Cuba had been closely linked for a while. Spain gave the U.S. control of the island as a result of the Spanish-American War, in 1898, and the independence of Cuba in 1901 came with strings attached that maintained the close link between the two governments. Cuba was also a popular tourist destination, conveniently located and famed for “palaces, plazas, colonnades, tropical parks.”

Still, the tradition of sitting presidents making trips outside the U.S. is a relatively new one, and it was even more so in Coolidge’s time. He was only the fifth chief executive ever to leave the U.S. during his tenure. And, TIME suggested as Coolidge set off for Key West, there to catch his ship to Havana, a superstition had attached itself to the tradition: Warren Harding had died shortly after his return from Canada, and the Treaty of Versailles was rejected shortly after the return of Woodrow Wilson (then the champion presidential traveler, by number of trips) from France.

In the early 20th century, U.S. policy in the Western Hemisphere evolved such that it became necessary for Coolidge to make the trip, whether or not it was bad luck. Though the Monroe Doctrine had asserted America’s place in the hemisphere about a century earlier, that role grew as Teddy Roosevelt decided to “speak softly and carry a big stick” and William Howard Taft embraced “dollar diplomacy.” By the late 1920s, a diplomatic gesture was needed to temper the resentment that power might provoke. To show, as TIME put it that week, “that though circumstance makes him seem a Caesar, the President of the U. S. is but the tribune of a peacefully potent and ambitious people.” By addressing the Pan-American Conference in Cuba, Coolidge could show that he saw his fellow leaders in the hemisphere as colleagues and peers, not subjects.

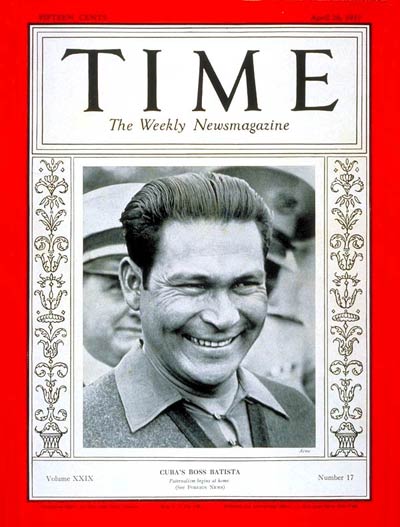

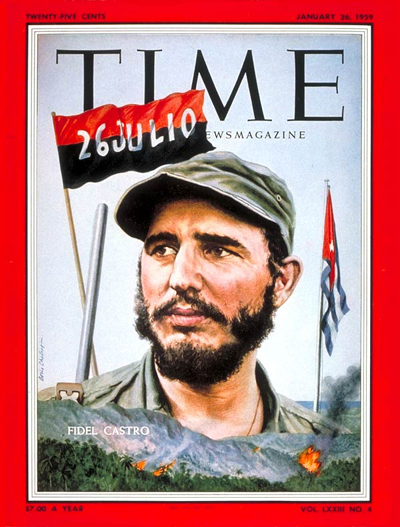

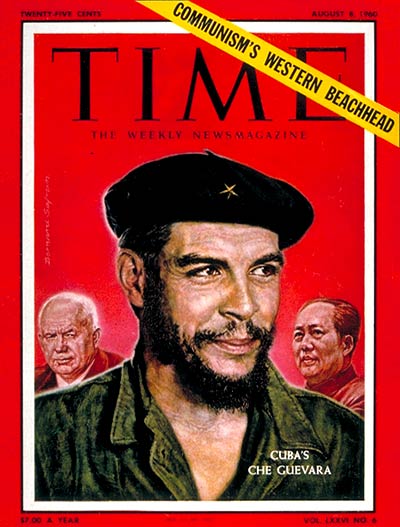

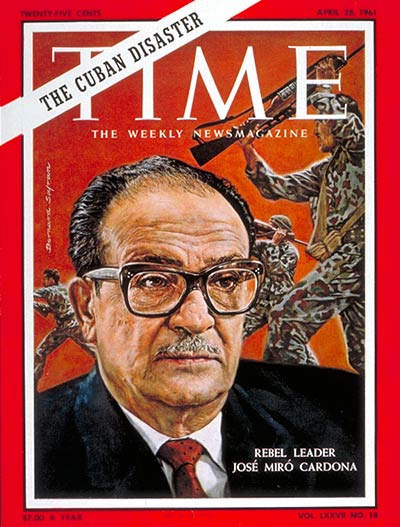

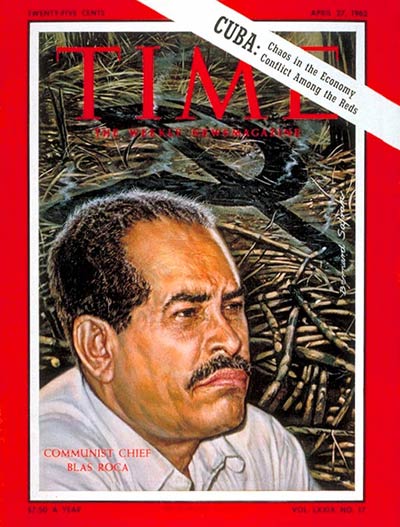

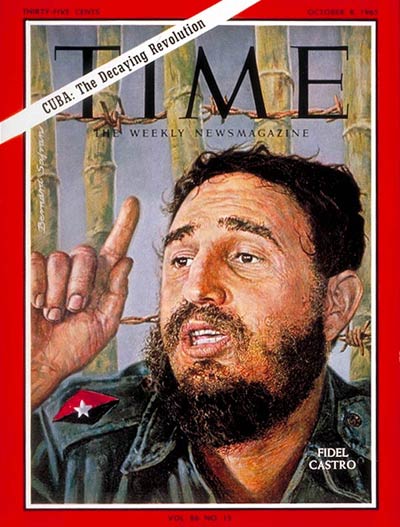

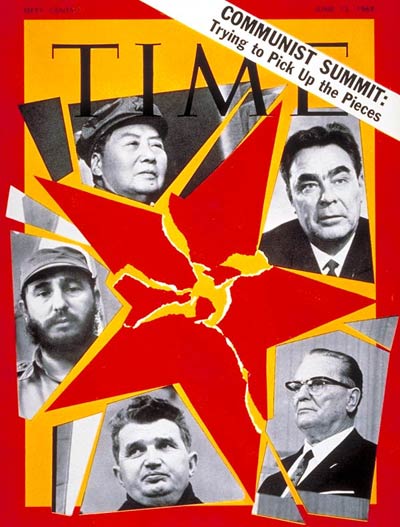

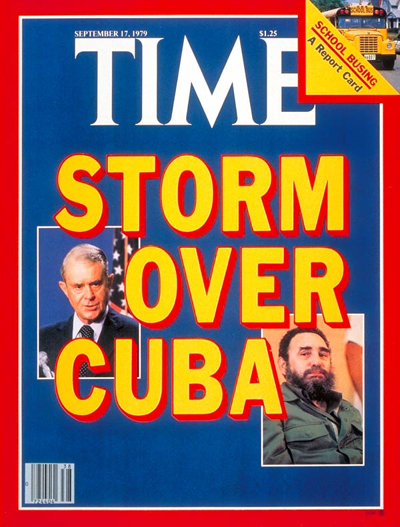

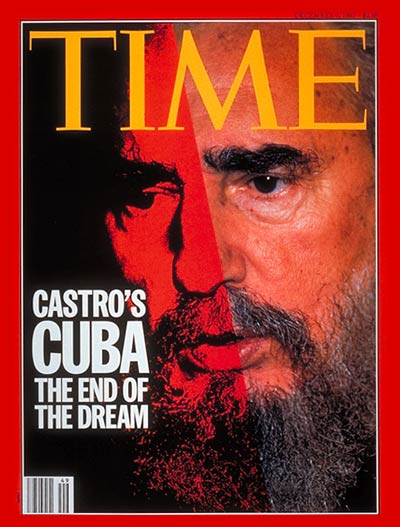

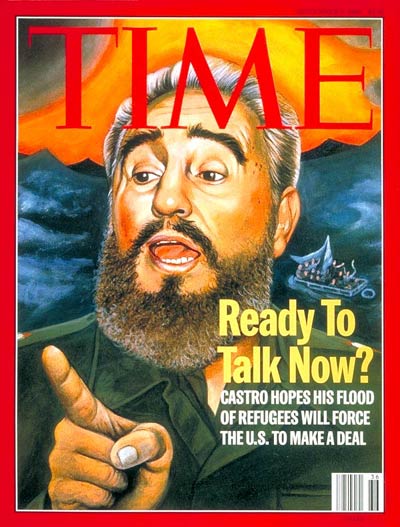

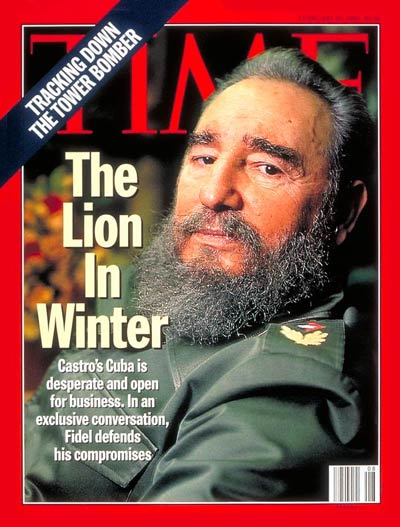

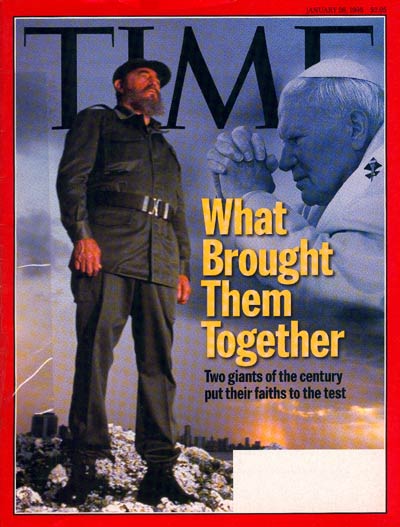

A History of Cuba-U.S. Relations in 13 TIME Covers

Sure enough, Coolidge’s speech was one of congratulations and camaraderie. The nations of the Americas were generally peaceful, forward-looking and respectful of one another, he said, and Cuba stood out as an example among them:

The very place where we are meeting is a complete demonstration of the progress we are making. Thirty years ago Cuba ranked as a foreign possession, torn by revolution and devastated by hostile forces. Such government as existed rested on military force. Today Cuba is her own sovereign. Her people are independent, free, prosperous, peaceful, and enjoying the advantages of self-government. The last important area has taken her place among the republics of the New World. Our fair hostess has raised herself to a high and honorable position among the nations of the earth. The intellectual qualities of the Cuban people have won for them a permanent place in science, art, and literature, and their production of staple commodities has made them an important factor in the economic structure of the world. They have reached a position in the stability of their government, in the genuine expression of their public opinion at the ballot box, and in the recognized soundness of their public credit that has commanded universal respect and admiration. What Cuba has done, others have done and are doing.

But the appearance of equality did not, to some, conceal the potential for an ulterior motive behind the outreach. “Around the Caribbean and down the whole continent south of it lies an empire which the U. S. would never want to conquer by shrapnel,” TIME explained, “but which it never will conquer by checkbooks and sales talk so long as there is any trace of powder in the air.” In fact, the extent of peace-time American influence in Cuba, as exemplified by Coolidge’s visit, would be just one of the many sticking points that would eventually erode relations between the two nations—a situation that, nearly a century later, President Obama hopes to improve.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com