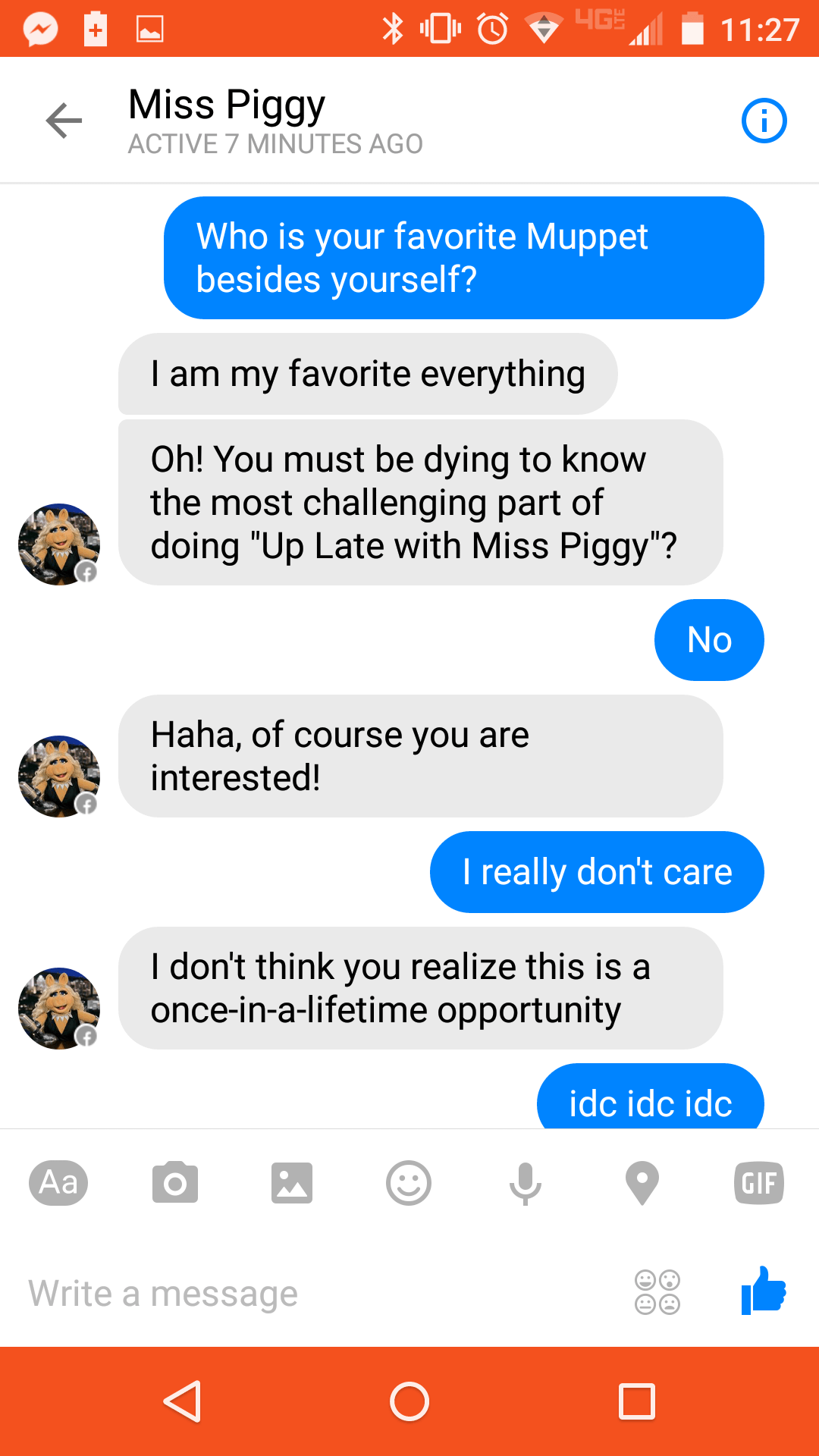

Miss Piggy doesn’t like it when I ask her about Kermit. We’re having a conversation in Facebook’s Messenger app, and the famous Muppet is trying to convince me to watch her fictional talk show Up Late With Miss Piggy, whose backstage hijinks provide the plot of ABC’s show The Muppets. She gushes about the show’s house band, Electric Mayhem—”VERY hairy”—and asks me whether I’d rate the program a 10 out of 10 or a mere 9 out of 10. But when I ask about her green ex-lover, she snaps. “I wish everyone would stop asking me about Kermit…I’ve moved on.”

Fine. I skip to why I really struck up this conversation. “Are you a robot?” Three dots waver across the screen as she types. “I am Miss Piggy, here to chat with all my fans.”

“Who created you?,” I ask.

“That is impossible to answer. I was born to be a star!”

This Miss Piggy is no puppet. The famous character has come alive in the form of a “chatbot,” or automated messaging software that tries to talk to users the way a real person would.

Computer programs that attempt to mimic human interactions have been around since the 1960’s. That’s when Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Joseph Weizenbaum created a bot called ELIZA, which borrowed psychotherapy techniques to hold simple conversations with users (“Tell me more…” is a common response of hers). Later, they found a home on desktop messaging clients like AOL Instant Messenger, on which users could ask for weather forecasts or hurl obscenities at bots like SmarterChild.

Chatbots went dormant as messaging transitioned away from desktops and onto mobile devices. But they’re poised for a resurgence in 2016. There are two reasons for this. First, artificial intelligence and cloud computing software has gotten much better thanks to improvements in cloud computing and machine learning. Second, bots could be big money. Companies from Facebook to Google are convinced there’s a buck to be made here, and they’re scrambling to make sure they don’t get left out. “Messaging is evolving as the next platform for applications and services, whether it’s games or commerce or transportation,” says mobile analyst and consultant Chetan Sharma.

Facebook is developing an all-purpose digital assistant for its Messenger app called M. Early tests show that M can handle everything from booking flight reservations to scoring concert tickets, though it does have some human help.

Meanwhile, the social network is also turning Messenger into a platform for lots of other services. Messenger users can, for instance, use the app to request a ride from Uber without having to open Uber’s own app. And there’s a growing number of robotic characters like Miss Piggy, which was developed by Disney and Imperson, a company that builds marketing bots. “Like you have apps, there will be a service store with service bots that will be created by other companies right on the messaging platform,” says Sharma. That’s helpful for users because it means less flipping around from app to app. But it’s even better for Facebook, which could make more money if marketers pay for the privilege to connect with users or if Facebook collects a fee on in-app transactions.

Google, meanwhile, is building a new messaging service with an emphasis on helpful bots, according to The Wall Street Journal. The timing makes sense. Google has faced challenges converting its successful desktop search business to the mobile world, where users often discover information through messaging apps and social networks rather than search queries. Bots could help Google recapture some of that activity. “With various messaging apps now becoming big, people can just live in them,” Google head of search Amit Singhal acknowledged in an interview with TIME last fall. “We worry about that all the time.”

Other platforms are further along in their chatbot experiments. On Kik, a messaging app aimed at teens, users can chat up as many as 100 different bots, ranging from an inebriated George Washington made to promote the Comedy Central show Drunk History to a Washington Post bot that takes users on a virtual road trip. Overall, 16 million of the app’s 240 million registered users have had at least one conversation with a bot.

“We think chat is something that will become like the app ecosystem,” says Paul Gray, director of platform services at Kik. “For a developer, it’s very easy to build a bot and it’s very easy to deploy. It’s much harder to build, deploy and maintain an app.”

For a better view of our bot-dominated future, take a look at China. There, people are already using popular messaging app WeChat to do everything from book medical appointments to shop for clothes. “If there’s one guiding light, it’s probably WeChat,” Sharma says. Some of that activity happens through text messaging, while other experiences look more like mobile websites in the WeChat app. A Microsoft-developed WeChat bot that simulates a conversational and empathetic persona has attracted millions of users.

Truly autonomous bots aren’t ready for primetime yet. Miss Piggy is a novelty, with any conversations inevitably leading back to promoting her show. Facebook’s M, while diverse in its functionality, is currently powered by humans as well as computers. And it’s unclear if Americans, who have been slow to adopt buzzy initiatives like social commerce, are ready to embrace bots the way that Chinese users have.

Still, it’s clear that Silicon Valley’s most powerful companies are going to try putting bots to work here. If they prove bots can actually be useful, more people will likely hop on board. “These bots that can figure out what the user wants or needs and can provide that service are going to be really important,” says Charma.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com