Mary-Louise Parker has never fit in. “Skulking through life as a loser was oddly shaming… and has continued to trail me through realities that flat out contradict it,” the actress writes in her debut book, Dear Mr. You.

Parker, who has found longterm success on the small screen (Weeds, The West Wing), the big one (Fried Green Tomatoes, Boys On the Side) and the stage (Proof), is certainly not a loser. But she is something of a loner. She has spurned Hollywood for a duplex in Brooklyn, where she writes sonnets and doles out vegan baked goods to her children’s friends. Here, amidst her neatly aligned poetry books and cozy furniture overflowing with pillows, she has deliberately checked out. “I may not know who the vice president is at any given time, but I probably know who the poet laureate is,” she says on a recent afternoon. Parker finds Twitter “a bit vulgar” and instead has chosen to accumulate her family’s photos on a floor-to-ceiling tree she cut out of a huge cardboard appliance box. The tree, she says, is her social network. Which means her social network is essentially her two kids, William Atticus and Caroline Aberash, and their diaper-wearing dog, Eleanor Roosevelt. And Parker likes it that way.

“I always look at people and wonder, What is it like to be the homecoming queen, the person who never feels misunderstood?” she says. “I think I’m always going to be someone who just feels a little bit alone.”

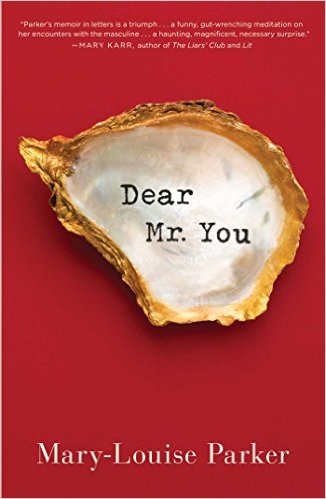

It should be no surprise then that Dear Mr. You is far from the typical Hollywood memoir, if one can call it a memoir at all. The collection of letters written to men throughout her life—her priest, her adopted daughter’s biological uncle, a man who wears only a loincloth, one of her pet goats—is a surprisingly poetic debut that’s been touted by the literary likes of Mary Karr, who Parker will play in Showtime’s Liar’s Club mini-series if it’s greenlit. Inspired by her memories of her late father and born from a column she wrote for Esquire, Parker wanted to celebrate “maleness” in all its glory and reflect on her occasionally tumultuous relationship with the opposite sex.

Though she shares surprisingly intimate moments, good and bad—a delightful “f-ck-your-lights-out fest” and less complimentary sentiments like “having sex with you was like making a snow angel under a rhino” —the identities of the men are concealed. Anyone looking for a rant against Billy Crudup, who left Parker when she was seven months pregnant for Claire Danes, will be disappointed, despite what gossip sites claim. Parker has refused to talk about the breakup for 11 years; the closest she comes in the book is an apology note to a cab driver to whom she yelled after the breakup, “I’m pregnant and alone.”

“Without sounding Pollyanna, I wanted to make something sweet. I didn’t want to make something that was an indictment, that was ugly, that was finger-wagging,” she says. “There’s a book there. Maybe that book sells more. But what a waste of paper.”

She’s not a Pollyanna. Could a naïve woman write to her acting school’s movement teacher, “I know you thought my lizard was inappropriate during the animal exercise. I really don’t recall trying to make my lizard overly sexual, per se”? But living in Parker’s universe, even for just a few hours, is like being in a fairy dreamland. When I ask if she’s experienced sexism in her career—a problem actresses like Meryl Streep, Jennifer Lawrence and Sandra Bullock have spoken out about—she rolls her eyes.

“It feels a little icky to me to complain about meaty roles or pay. And hear me when I say that we need to fight for equal pay for women in general—for teachers or nurses or policewomen. Actresses, not so much,” she says. “Do you really want to hear about Gwyneth Paltrow talk about how she doesn’t make enough money? I don’t.”

She’s had bigger problems, and her book digs deep, dressing serious issues in humor while often affording them the gravity they deserve. In a letter titled “Dear Cerberus” she merges three terrible exes into the mythical three-headed dog that guarded the underworld. One of those men drags her into a public bathroom and punishes her for dressing like a “slut” by sexually assaulting her. “You left me staring in the bathroom mirror, pants down,” she writes. “That’s actually a swell game if you play it right, but this was not that.” In another story, she writes of a building frustration with a boyfriend that ended with her stabbing him in the hand with a fork.

“You say nothing, you say nothing, you say nothing, and now my fork is in your thumb,” she tells me. “I think there’s a thing with little girls where you think at a certain point love is just going to show up. And when it doesn’t, you think, am I going to be alone my entire life? And then when men start paying attention to you, you fear their rejection.”

Maybe it’s our biological fate as women to be needy, she muses. Maybe it’s just her. “I want a man who bores the sh-t out of me,” she says. “But I’m attracted to extremes. Hopefully you are not.”

She offers advice on how to avoid the Cerberus or, better yet, confront him. “In the letter to my daughter’s future love, I tell him to treat her badly. It will serve to make her more compassionate,” she says. Before you critique her dubious parenting advice, know that she also writes in this letter: “Yes, you may have had a difficult childhood, but please let me introduce myself: Hello, I am the woman who doesn’t give a sh-t.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com