In 2013, when TIME started naming an Instagram Photographer of the Year, David Guttenfelder was a natural choice. The multiple award-winner and then chief Asia photographer for the Associated Press had broken new ground, using the photo-sharing app to post striking and intimate pictures of everyday life in North Korea, a country that had remained isolated and enigmatic for too long. Guttenfelder’s use of Instagram made sense: it allowed him to reach a wide audience, bypassing the traditional news filters.

In 2014, documentary photographer Matt Black earned the honor thanks to his innovative use of the platform’s mapping technology. Instagram allowed him to add geographic coordinated to his images, forcing his followers to acknowledge the wide geographic range of poverty, an issue he had been capturing for two decades.

This year, the search for Instagram Photographer of 2015 was a more complicated one—not that it lacked worthy candidates. Chien-Chi Chang (@chien_chi_chang), Sacha Lecca (@sachalecca), Ruddy Roye (@ruddyroye) and Petra Colins (@petrafcollins) all made the final shortlist for their work, but we were looking for a photographer with a unique approach to the platform itself.

For that reason, TIME’s pick for Instagram Photographer of the Year 2015 is Stacy Kranitz (@stacykranitz). She uses Instagram as “it was intended to be used,” as Matt Black put it: “To witness things as they happen.”

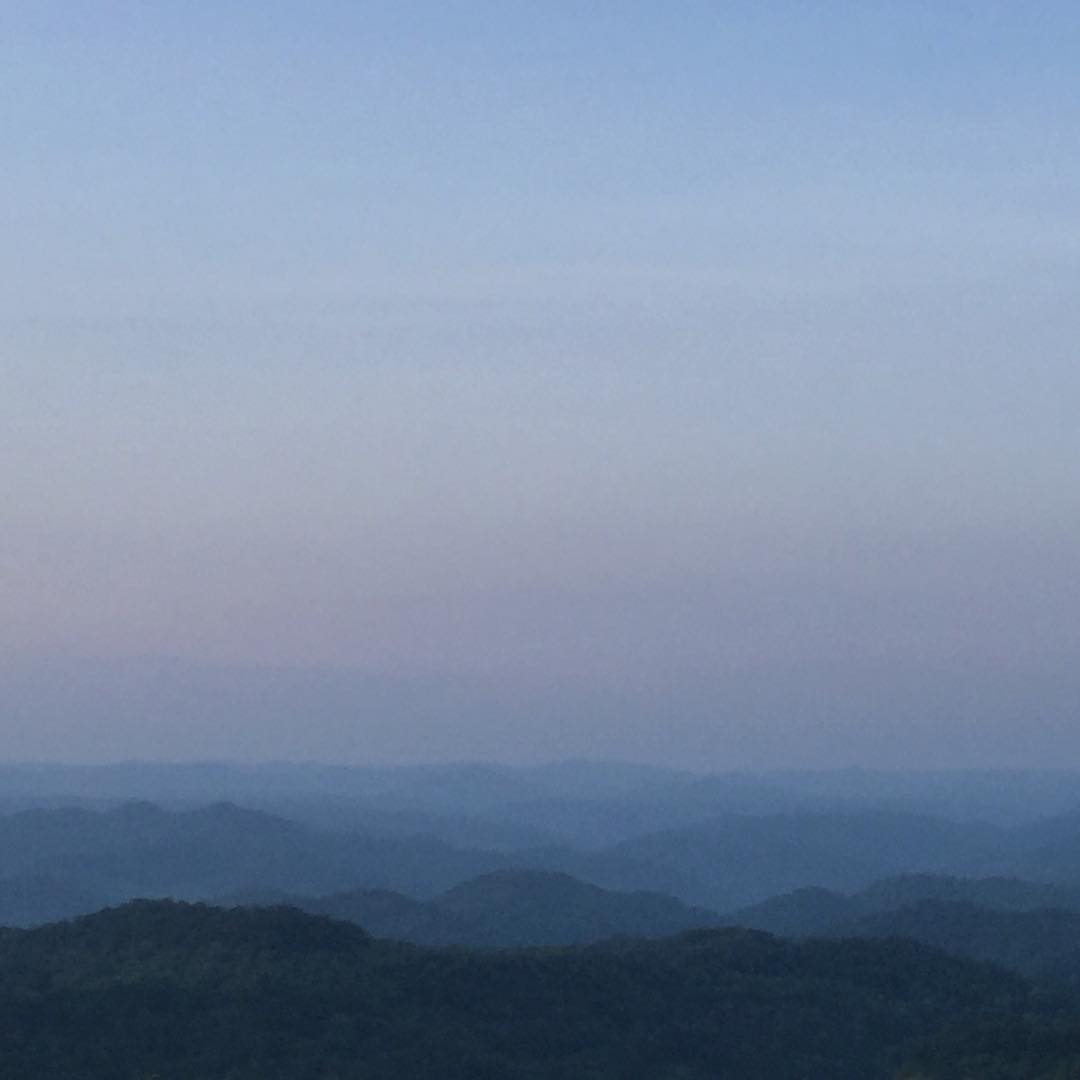

Kranitz, a Kentucky native who now lives in California when she’s not traveling, uses Instagram to explore the Appalachian region with intensely personal photographs.

Kranitz’s interest in photography was sparked by her passionate curiosity—she kept a Harriet the Spy-style notebook as a child, until another kid found it and made her judgments about their neighbors public—but she was initially interested in pursuing that course as a film director. It was after finding that she lacked the natural urge to make groups of people act a certain way, she turned to photography for its solitary nature. Her photographic career had a false start too: she embarked on a project as a street photographer roaming the streets of New York while “aggressively attacking people with my camera,” she says, as she dealt with “a lot of demons to work out from my childhood.” An unfortunate case of plantar warts, a blessing in disguise that made it painful for her to walk, brought that period to an end, forcing her to work more intimately with people.

“I wanted to use the camera as an excuse to get to know people and get close to them,” she says. “This has been at the core of my work ever since.”

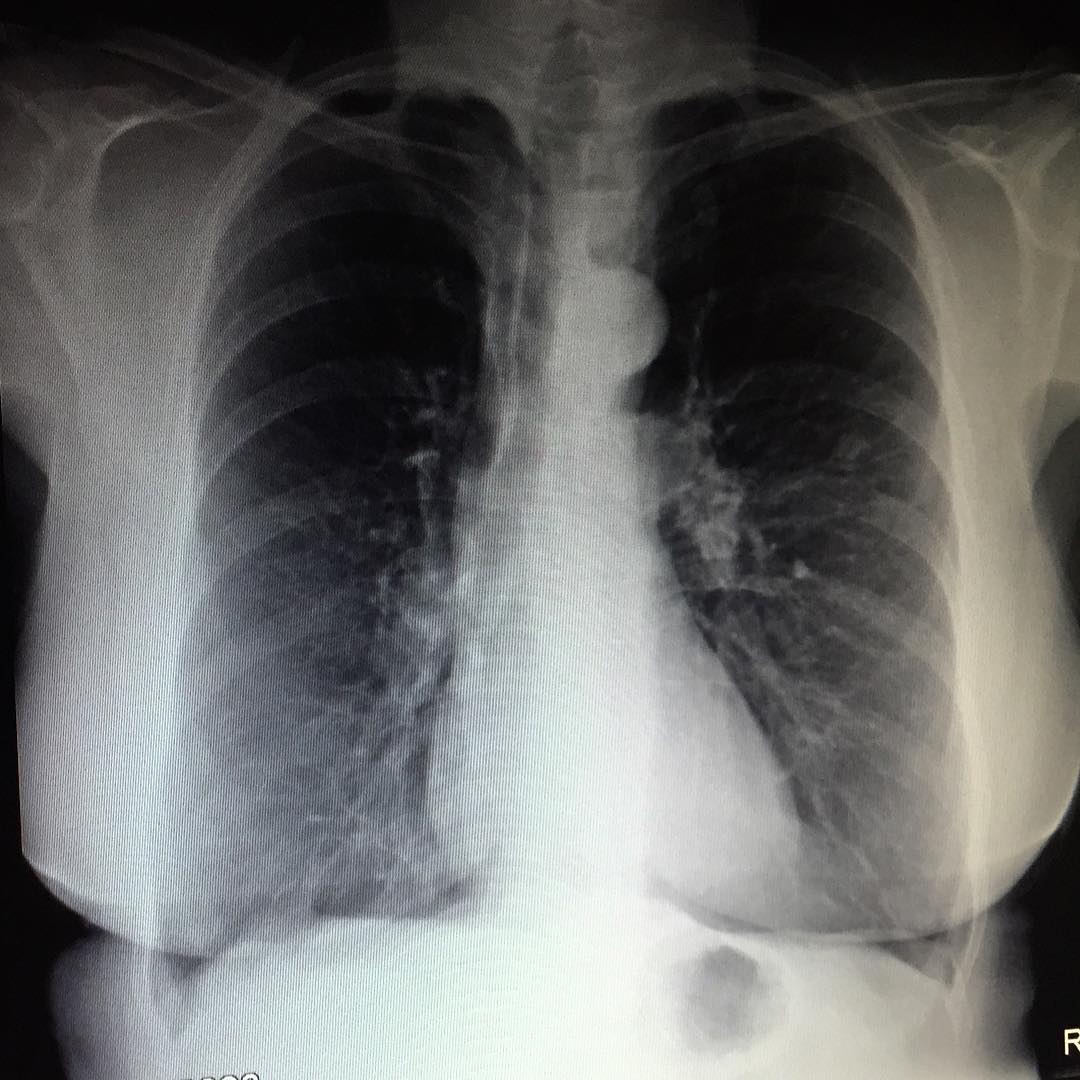

As Kranitz worked on her project From the Study of Post-Pubescent Manhood—“an intense, visceral and unglamorized engagement with a raw and elementary, almost primeval, world of adolescence, where young testosterone, adrenaline, and substance-fueled males partake in the recreational rituals of coming of age, while living life on the edge,” as TIME wrote earlier this year—she realized that the place she was staying was historically significant for its rural poverty. “I started traveling through the region to get a better sense of what poverty looked like in Appalachia,” she says. “I was staying with my friend in Southern Ohio and I would get in my car and travel for three weeks through the region exploring and meeting people. I would camp at night in Wal-Mart parking lots or at campgrounds and read some of the significant books that defined the region.”

Her readings included Christy by Catherine Marshall, James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Jack Weller’s Yesterday’s People and Harry Caudill’s Night Comes to Cumberlands. “Before I knew it, the project had become this immense inquiry into the meaning of poverty and our cultural relationship to images of poverty,” she says. “It became, for me, a reckoning with the fantasy of objective representation.”

In fact, she tells TIME, the work has had a transformative effect on her methodology. “I ask a lot of questions as I make the work,” she says. “What does it mean to represent someone in a photograph? How is my representation different or the same as those who have come before me to depict this place and its people? Where does the line between subjectivity and objectivity exist? Is truth subjective? How can a photograph demystify stereotypes when the viewer is trained to seek stereotypes out and fix people in their own vision of what they think the other represents? Is culture something that can be gotten right? How do I make work that explores my complicated relationship to my subjects?”

While other photographers try to detach themselves from their subjects in a bid to create images that will offer, they say, a truer representation of events, Kranitz embraces the fact that her presence directly impacts her subjects and her photographs. That’s why she doesn’t shy away from picturing herself among them, sharing on Instagram selfies she’s taken or portraits her “subjects” have snapped. She also readily admits doing drugs with them or, in another case, engaging into a romantic and sexual relationship with one of her subjects. “I’m interested in blurring the boundaries of my personal life and my professional life,” she told Dazed earlier this year, “as I find those boundaries problematic and unhealthy.”

Her unconventional approach has attracted controversy, especially in a year when the photojournalism community has been questioning issues of representation. In October, the aforementioned Dazed article ran with a headline emphasizing the fact that Kranitz had sex with her subjects. There’s also Kranitz’s tense relationship with Roger May, a documentary photographer and the founder of the crowdsourced project Looking at Appalachia. While both shooters share the same “commitment to dialogue about photography in Appalachia,” as May wrote in July, Kranitz’s photographs, he claims, perpetuate the idea of a “drug and alcohol-fueled Appalachia.”

But for Guttenfelder, who, along with Black, was asked to cast a vote, Kranitz’s work, which bridges the gap between personal and professional, remains “true, honest, raw, beautiful,” he says.

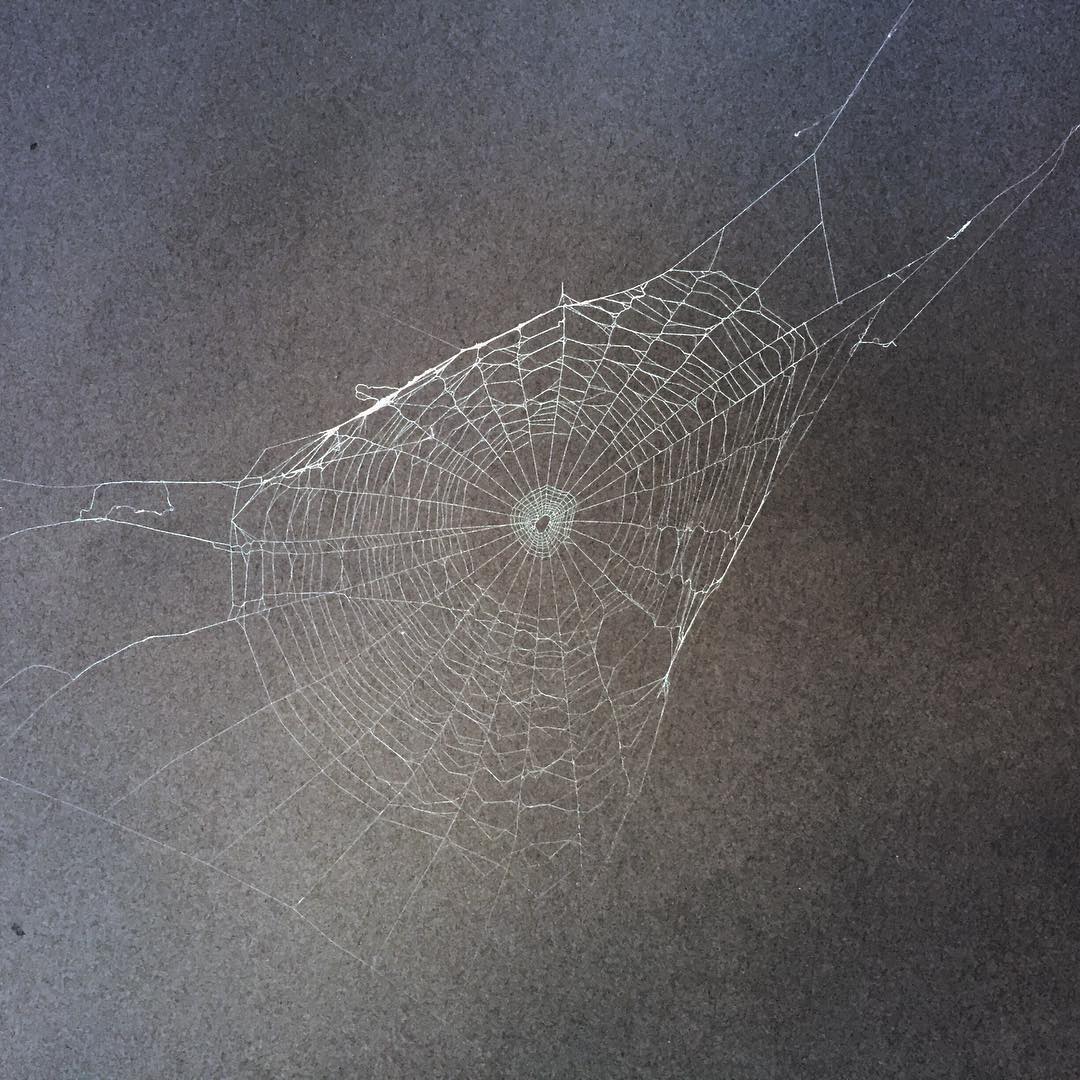

Kranitz first joined Instagram three years ago during her travels in central Appalachia. “I was feeling lonely and I missed all of the disparate people in my life,” she says. “I wanted a way to connect with them. The platform seemed ideal for this.” Since then, Kranitz hasn’t veered away from her original intentions. “I see Instagram as a sketchpad, notebook or diary. It has become a personal archive, a collection of thoughts, moods and feelings,” she says—echoing the millions of people who use Instagram in the same way.

Stacy Kranitz is a documentary photographer. Follow her on Instagram @stacykranitz.

Kira Pollack, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com