As the star of the new movie Brooklyn, Saoirse Ronan is tasked with portraying an Irish immigrant in 1950s New York City as a singular woman in a unique situation. But transatlantic love triangles aside, the experiences of the fictional Eilis Lacey would have been as common as Irish pubs are in today’s Midtown Manhattan.

In the novel on which the movie is based, a best-seller by Colm Tóibín, Eilis moves from small-town Ireland, where she struggles to find work, to Brooklyn. A priest facilitates the move, finds her a job at an Italian-run department store and lodging in an Irish women’s boarding house, and sets her up to take night classes in bookkeeping. Such a trajectory would have been typical for an Irish woman moving to New York at the time—but to fully understand Eilis’s ’50s experience, it’s necessary to back up to the first boom of Irish immigration to America, in the 1840s.

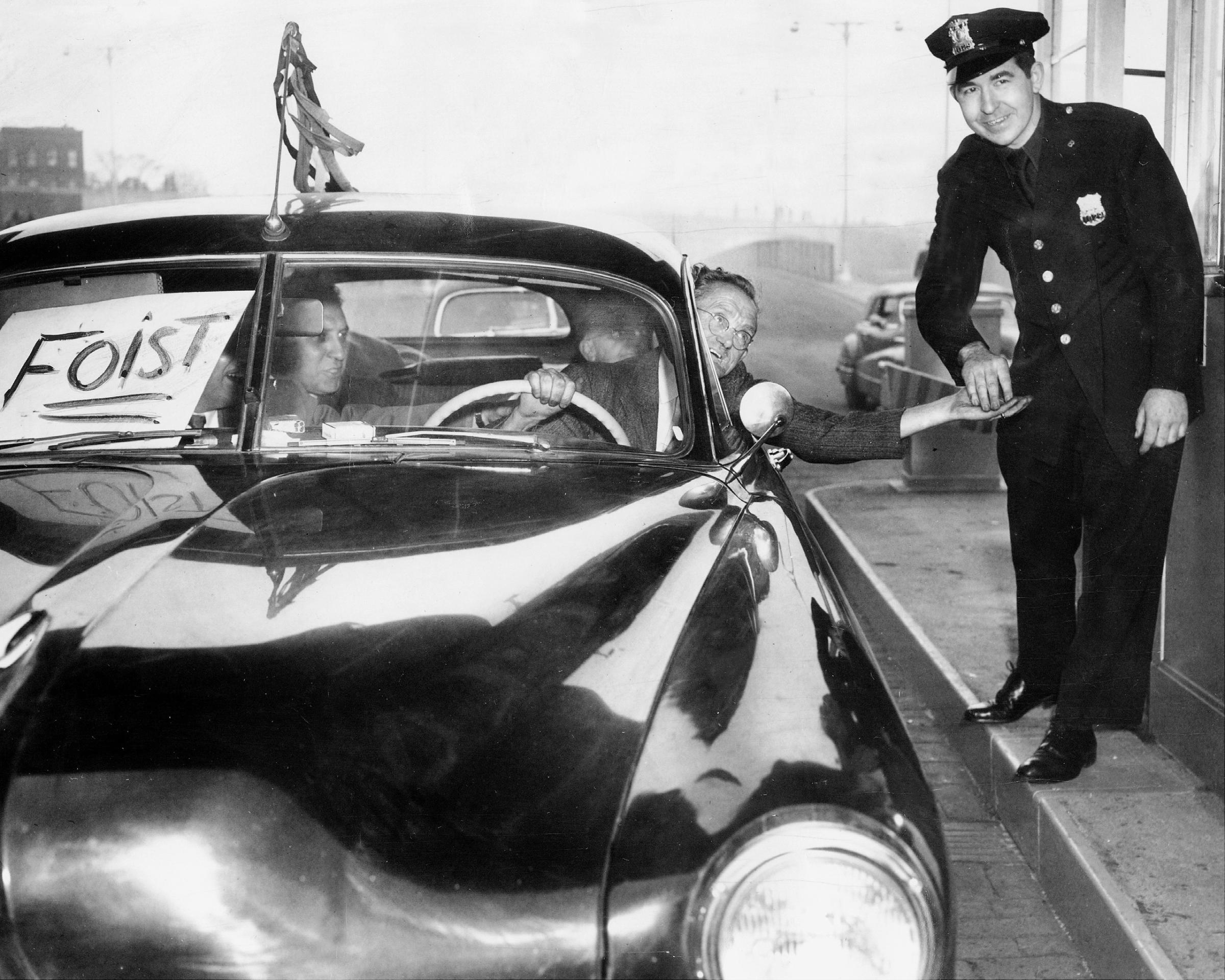

When the potato famine sent droves of immigrants to America, New York City saw the beginning of a new immigrant infrastructure in which the Irish would eventually dominate powerful unions, civil service jobs and Catholic institutions in the city. Given their firm hold on construction work during a critical period of growth in Manhattan, “Bono of U2 exaggerated only slightly when he said the Irish built New York,” says Stephen Petrus, the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the New York Historical Society. While the Great Depression and World War II had decreased the rate of Irish immigration, newcomers to the city in 1950 would still find vibrant Irish enclaves with steady jobs available, an Irish mayor in William O’Dwyer and an Irish-American Cardinal in Francis Spellman, who was “highly influential, not just in religion, but in politics,” Petrus says.

Meanwhile, economic conditions in Ireland were a different situation. As Irish-American historian and novelist Peter Quinn explains, “The country wasn’t in the Second World War, it had been kind of cut off from the rest of the world, and it wasn’t part of the Marshall Plan. So it was still a very rural country.” The economy was at a standstill, while the U.S. was booming. Some 50,000 immigrants left Ireland for America in the ’50s, about a quarter of them settling in New York.

And, within that community, women played an important role. During the 19th century, the wave of Irish was “the only immigration where there were a majority of women,” Quinn says. And, thanks to a culture that supported nuns and teachers, those women were often able to delay marriage and look for jobs. By the mid 20th century, many Irish women—who also benefited from the ability to speak English—were working in supermarkets, utility companies, restaurants and, like Eilis, department stores. The fact that Eilis finds her job through her priest is also typical. “[The Catholic Church] was an employment agency. It was the great transatlantic organization,” Quinn says. “If you came from Ireland, everything seemed different, but the church didn’t. It was a comfort that way, and it was a connection.”

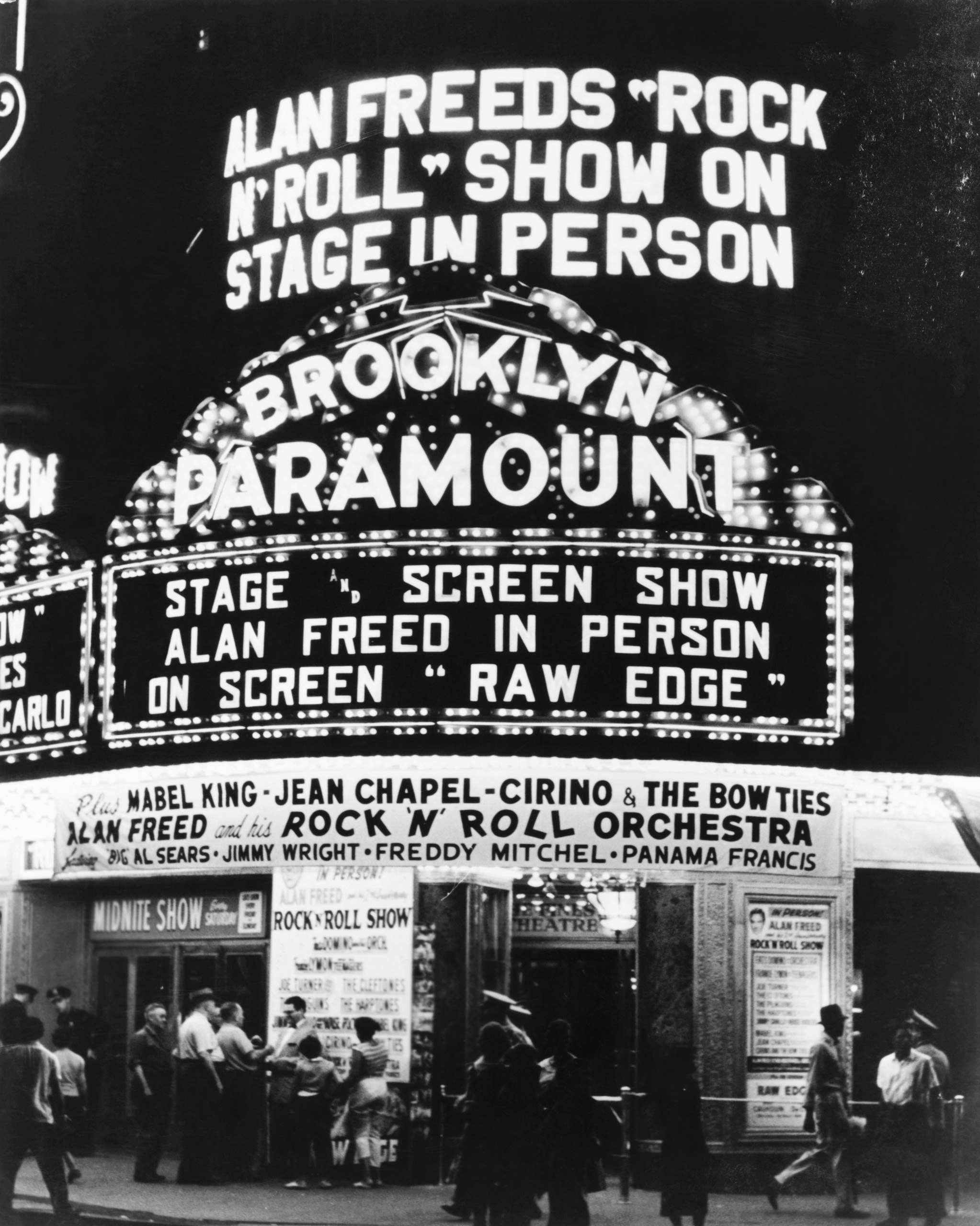

It’s fitting, then, that Eilis meets her love interest, the Italian-American Tony, at a parish dance. These were tremendously popular social events where women could meet men while under the protective supervision of their priest. No alcohol would have been on offer, which added another layer of safety. And it’s not at all strange that Eilis would strike up with an Italian-American man rather than a fellow Celt. “When people talked about intermarriage in the ‘50s, they weren’t talking about black-white, they were talking about Irish-Italian,” Quinn says.

But there is one place where Eilis’ story departs from the historic norm, and it’s the crux of the plot: her trip home to Ireland and the possibility that the homesick protagonist might move back permanently. Though many immigrants would send money home to relatives who had stayed Ireland, Quinn says, “it was rare for Irish immigrants to go back to live.” Even so, though Tóibín’s protagonist is fictional, the heartache and growing pains experienced by so many women with stories like hers would have been unmistakably real.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com