Hillary Clinton testified before the House Select Committee on Benghazi on Thursday, where she faced questions about the 2012 attack in Libya during her time as Secretary of State. Here is a transcript of her opening statement:

Thank you Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Cummings, members of the committee. The terrorist attacks at our diplomatic compound and later, at the CIA post in Benghazi, Libya on September 11, 2012 took the lives of four brave Americans: Ambassador Chris Stevens, Sean Smith, Glen Doherty, and Tyrone Woods.

I am here to honor the service of those four men, the courage of the Diplomatic Security agency and the CIA officers who risked their lives that night, and the work their colleagues do every single day all over the world.

I knew and admired Chris Stevens. He was one of our nation’s most accomplished diplomats. Chris’s mother liked to say that he had sand in his shoes, because he was always moving, always working, especially in the Middle East that he came to know so well.

When the revolution broke out in Libya, we named Chris as our envoy to the opposition. There was no easy way to get him into Benghazi to begin gathering information and meeting those Libyans who were rising up against the murderous the dictator Qadhafi, but he found a way to get himself there on a Greek cargo ship, just like a 19th century American envoy. But his work was very much 21st century hard-nosed diplomacy.

It is a testament to the relationships that he built in Libya that on the day following the awareness of his death, tens of thousands of Libyans poured into the streets in Benghazi. They held signs reading “thugs don’t represent Benghazi or Islam.” “Sorry people of America, this is not the behavior of our Islam or our Prophet.” “Chris Stevens, a friend to all Libyans.”

Although I didn’t have the privilege of meeting Sean Smith personally, he was a valued member of our State Department family. An Air Force veteran, he was an Information Management officer, who had served in Pretoria, Baghdad, Montreal, and The Hague.

Tyrone Woods and Glen Doherty worked for the CIA. They were killed by mortar fire at the CIA’s outpost in Benghazi, a short distance from the diplomatic compound. They were both former Navy SEALs and trained paramedics with distinguished records of service, including in Iraq and Afghanistan.

As Secretary of State, I had the honor to lead and the responsibility to support nearly 70,000 diplomats and development experts across the globe.

Losing any one of them, as we did in Iraq, Afghanistan, Mexico, Haiti, and Libya during my tenure, was deeply painful for our entire State Department and USAID family, and for me personally.

I was the one who asked Chris to go to Libya as our envoy. I was the one who recommended him to be our Ambassador to to the President.

After the attacks, I stood next to President Obama as Marines carried his casket and those of the other three Americans off the plane at Andrews Air Force Base.

I took responsibility. And, as part of that, before I left office, I launched reforms to better protect our people in the field and help reduce the chance of another tragedy happening in the future.

What happened in Benghazi has been scrutinized by a nonpartisan, hard-hitting Accountability Review Board, seven prior Congressional investigations, multiple news organizations, and, of course, our law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

So today I would like to share three observations about how we can learn from this tragedy and move forward as a nation.

First, America must lead in a dangerous world, and our diplomats must continue representing us in dangerous places.

The State Department sends people to more than 270 posts in 170 countries around the world.

Chris Stevens understood that diplomats must operate in many places where our soldiers do not, where there are no other boots on the ground, and safety is far from guaranteed. In fact, he volunteered for just those assignments.

He also understood we will never prevent every act of terrorism or achieve perfect security, and that we inevitably must accept a level of risk to protect our country and advance our interests and values.

And make no mistake: the risks are real. Terrorists have killed more than sixty-five American diplomatic personnel since the 1970s and more than a hundred contractors and locally employed staff.

Since 2001, there have been more than one hundred attacks on U.S. diplomatic facilities around the world.

But if you ask our most experienced ambassadors, they’ll tell you they can’t do their jobs for us from bunkers.

It would compound the tragedy of Benghazi if Chris Stevens’ death and the death of the other three Americans ended up undermining the work to which he and they devoted their lives.

We have learned the hard way when America is absent, especially from unstable places, there are consequences. Extremism takes root, aggressors seek to fill the vacuum, and security everywhere is threatened, including here at home.

That’s why Chris was in Benghazi. It’s why he had served previously in Syria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Jerusalem during the second intifada.

Nobody knew the dangers of Libya better — a weak government, extremist groups, rampant instability. But Chris chose to go to Benghazi because he understood America had to be represented there at that pivotal time.

He knew that eastern Libya was where the revolution had begun and that unrest there could derail the country’s fragile transition to democracy. And if extremists gained a foothold, they would have the chance to destabilize the entire region, including Egypt and Tunisia.

He also knew how urgent it was to ensure that the weapons Qadhafi had left strewn across the country, including shoulder-fired missiles that could knock an airplane out of the sky, did not fall into the wrong hands. The nearest Israeli airport is just a day’s drive from the Libyan border.

Above all, Chris understood that most people, in Libya or anywhere, reject the extremists’ argument that violence can ever be a path to dignity or justice. That’s what those thousands of Libyans were saying after they learned of his death. He understood there was no substitute for going beyond the Embassy walls and doing the hard work of building relationships.

Retreat from the world is not an option. America cannot shrink from our responsibility to lead. That doesn’t mean we should ever return to the go-it-alone foreign policy of the past, a foreign policy that puts boots on the ground as a first choice rather than a last resort. Quite the opposite.

We need creative, confident leadership that harnesses all of America’s strengths and values. Leadership that integrates and balances the tools of diplomacy, development, and defense.

And at the heart of that effort must be dedicated professionals like Chris Stevens and his colleagues, who put their lives on the line for a country—our country—because they believed – as I do – that America is the greatest force for peace and progress the world has ever known.

My second observation is this: We have a responsibility to provide our diplomats with the resources and support they need to do their jobs as safely and effectively as possible.

After previous deadly attacks, leaders from both parties and both branches of government came together to determine what went wrong and how to fix it for the future. That’s what happened during the Reagan administration, when Hezbollah attacked our embassy. They killed 63 people, including 17 Americans. And then in a later attack, attacked our Marine barracks and killed so many more. Those two attacks in Beirut resulted in the deaths of 258 Americans.

It’s what happened during the Clinton administration when al Qaeda bombed our embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing more than two hundred people, wounding more than two thousand people, and killing twelve Americans. It’s what happened during the Bush administration after 9/11.

Part of America’s strength is we learn, we adapt, and we get stronger.

After the Benghazi attacks, I asked Ambassador Thomas Pickering, one of our most distinguished and longest-serving diplomats, along with Admiral Mike Mullen, the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff appointed by President George W. Bush, to lead an Accountability Review Board. This is an institution that the Congress set up after the terrible attacks in Beirut. There have been eighteen previous Accountability Review Boards. Only two have ever made any of their findings public. The one following the attacks on our embassies in East Africa and the one following the attack on Benghazi. The Accountability Review Board did not pull a single punch. They found systemic problems and management deficiencies in two State Department bureaus.

And the Review Board recommended twenty-nine specific improvements. I pledged that by the time I left office, every one would be on the way to implementation. And they were. More Marines were slated for deployment to high-threat embassies. Additional Diplomatic Security agents were being hired and trained.

And Secretary Kerry has continued this work. But there is more to do. And no administration can do it alone. Congress has to be our partner, as it has been after previous tragedies.

For example, the Accountability Review Board and subsequent investigations have recommended improved training for our officers before they deploy to the field. But efforts to establish a modern joint training center are being held up by Congress. The men and women who serve our country deserve better.

Finally, there is one more observation I’d like to share:

I traveled to 112 countries as Secretary of State. Every time I did, I felt great pride and honor representing the country that I love. We need leadership at home to match our leadership abroad. Leadership that puts national security ahead of politics and ideology.

Our nation has a long history of bipartisan cooperation on foreign policy and national security. Not that we always agree — far from it — but we do come together when it counts.

As Secretary of State, I worked with the Republican chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to pass a landmark nuclear arms control treaty with Russia. I worked with Republican Leader, Senator Mitch McConnell, to open up Burma, now Myanmar, to find democratic change.

I know it’s possible to find common ground, because I have done it.

We should debate on the basis of fact, not fear. We should resist denigrating the patriotism or loyalty of those with who we disagree.

So I am here. Despite all the previous investigations and all the talk about partisan agendas, I am here to honor those we lost and to do what I can to aid those who serve us still.

And my challenge to you, members of this Committee, is the same challenge I put to myself.

Let’s be worthy of the trust the American people have bestowed upon us. They expect us to lead. To learn the right lessons. To rise above partisanship and to reach for statesmanship.

That’s what I tried to do every day as Secretary of State. And it’s what I hope we all strive for here today and into the future. Thank you.

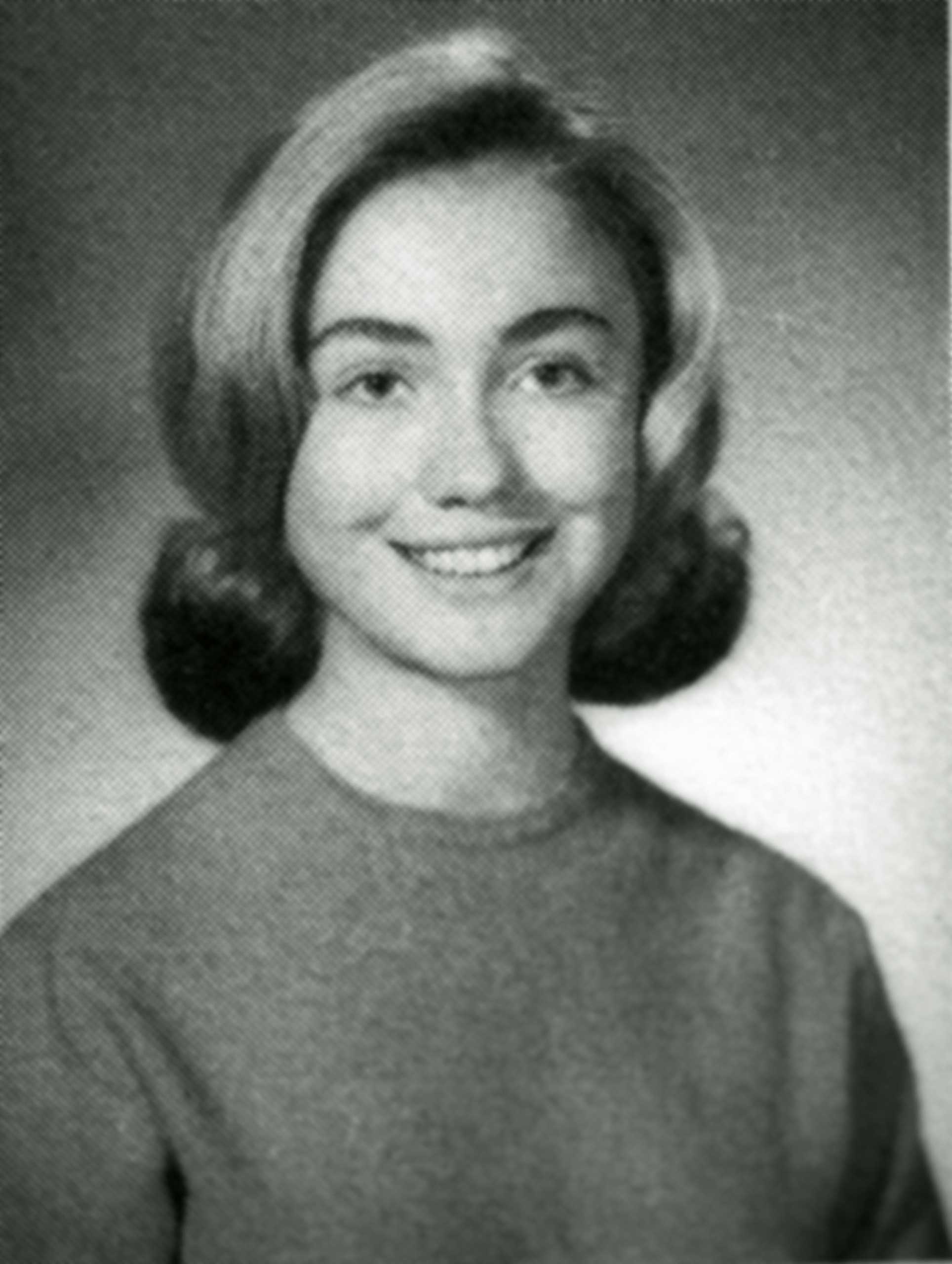

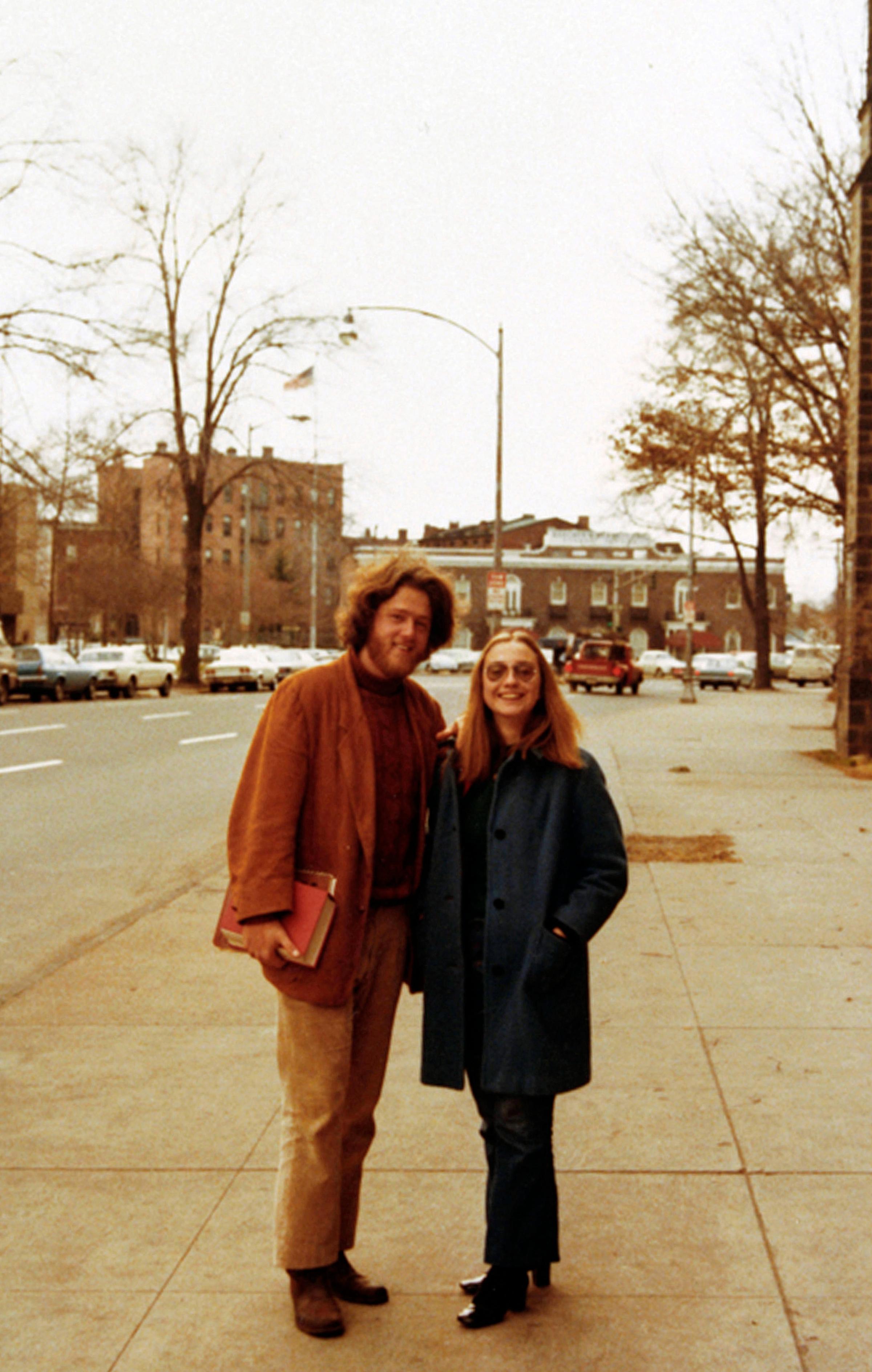

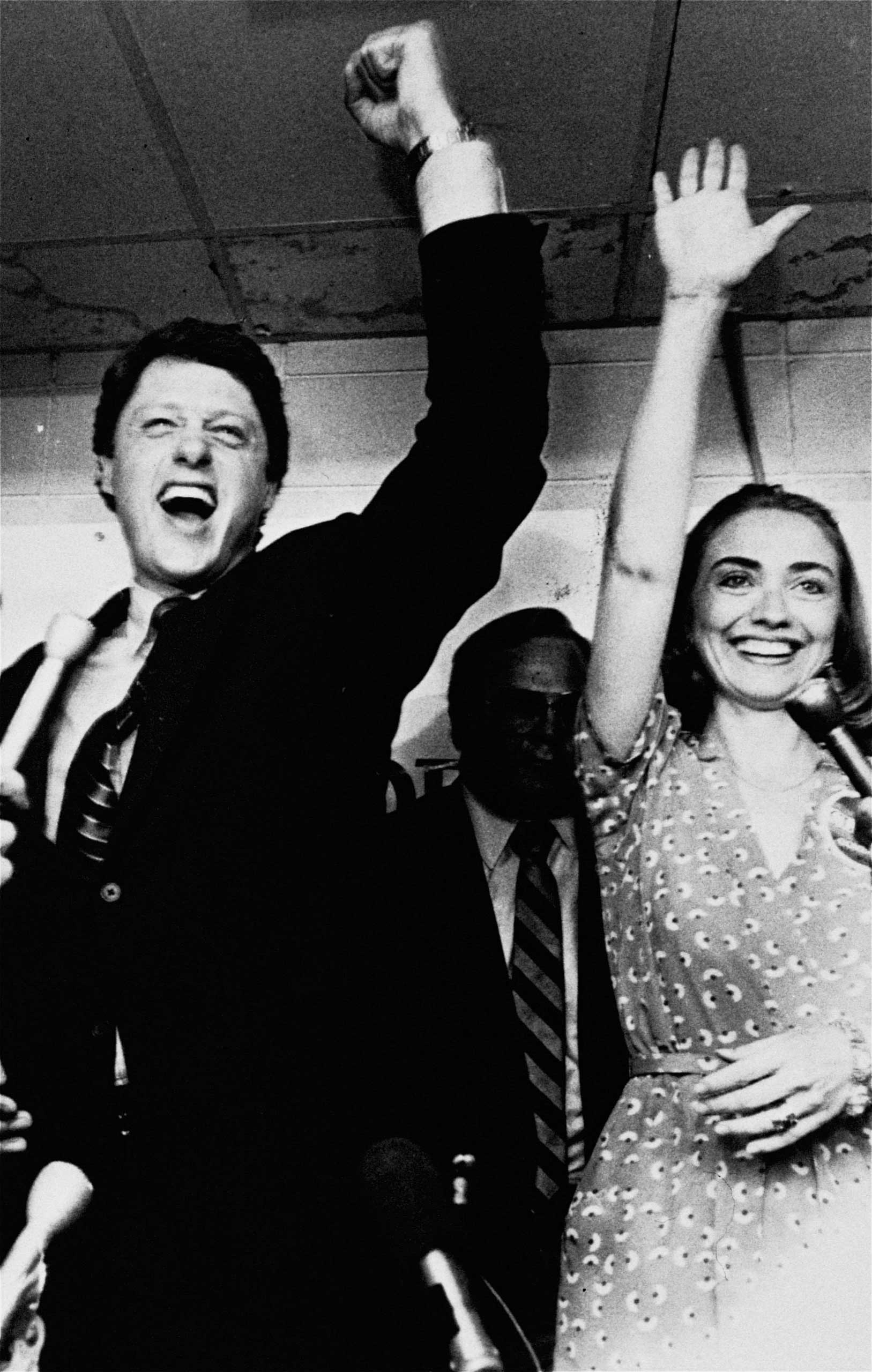

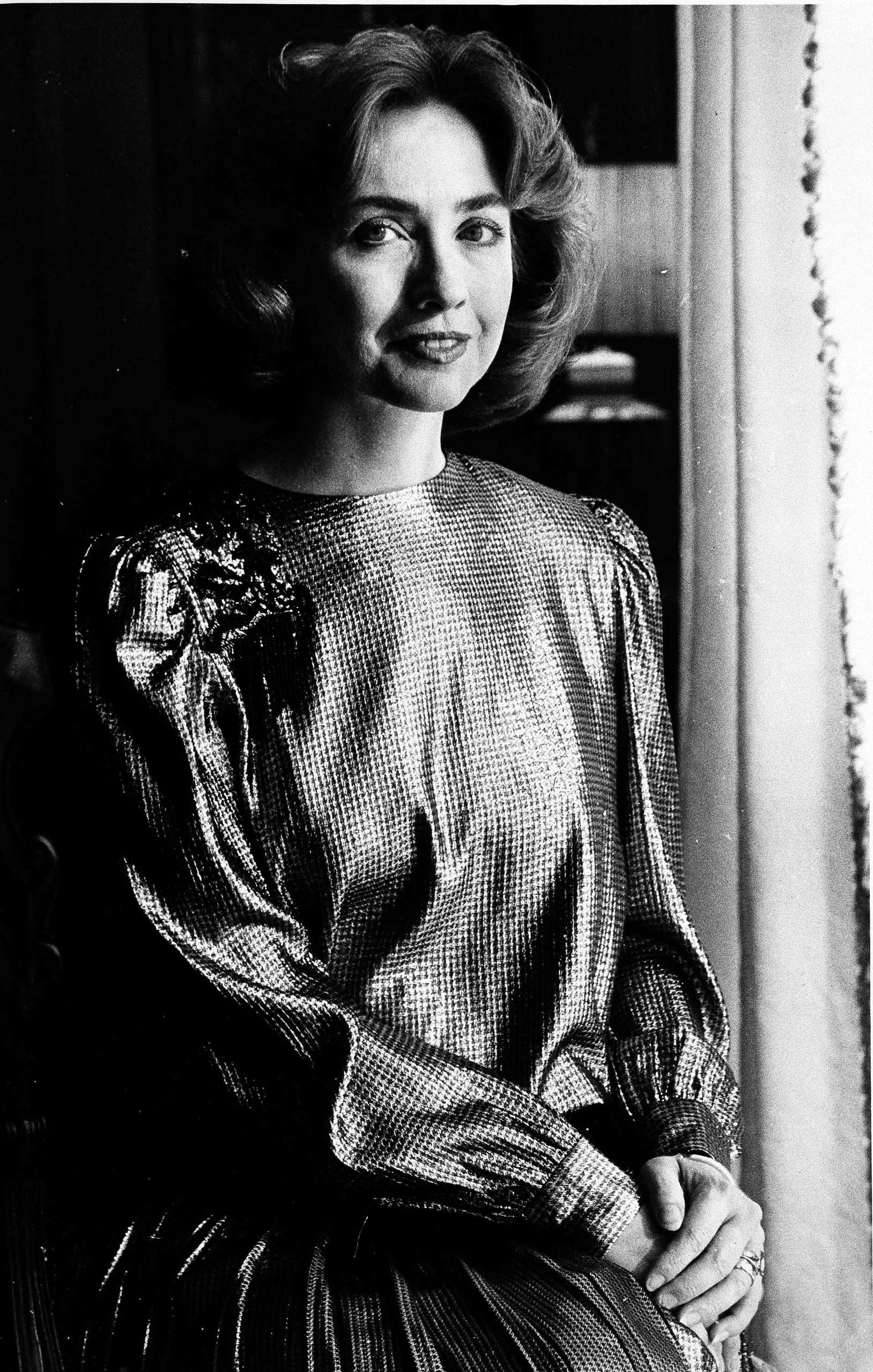

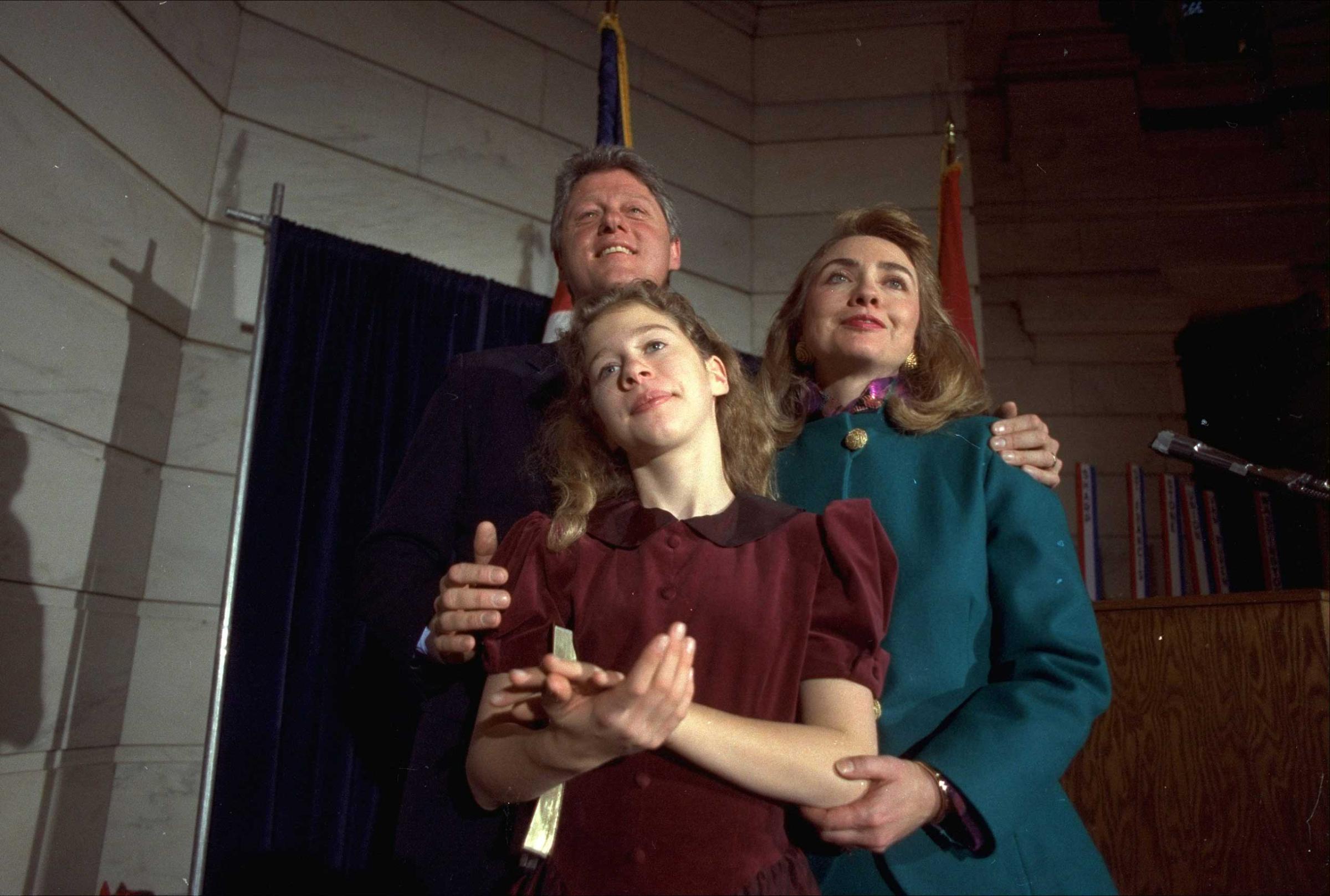

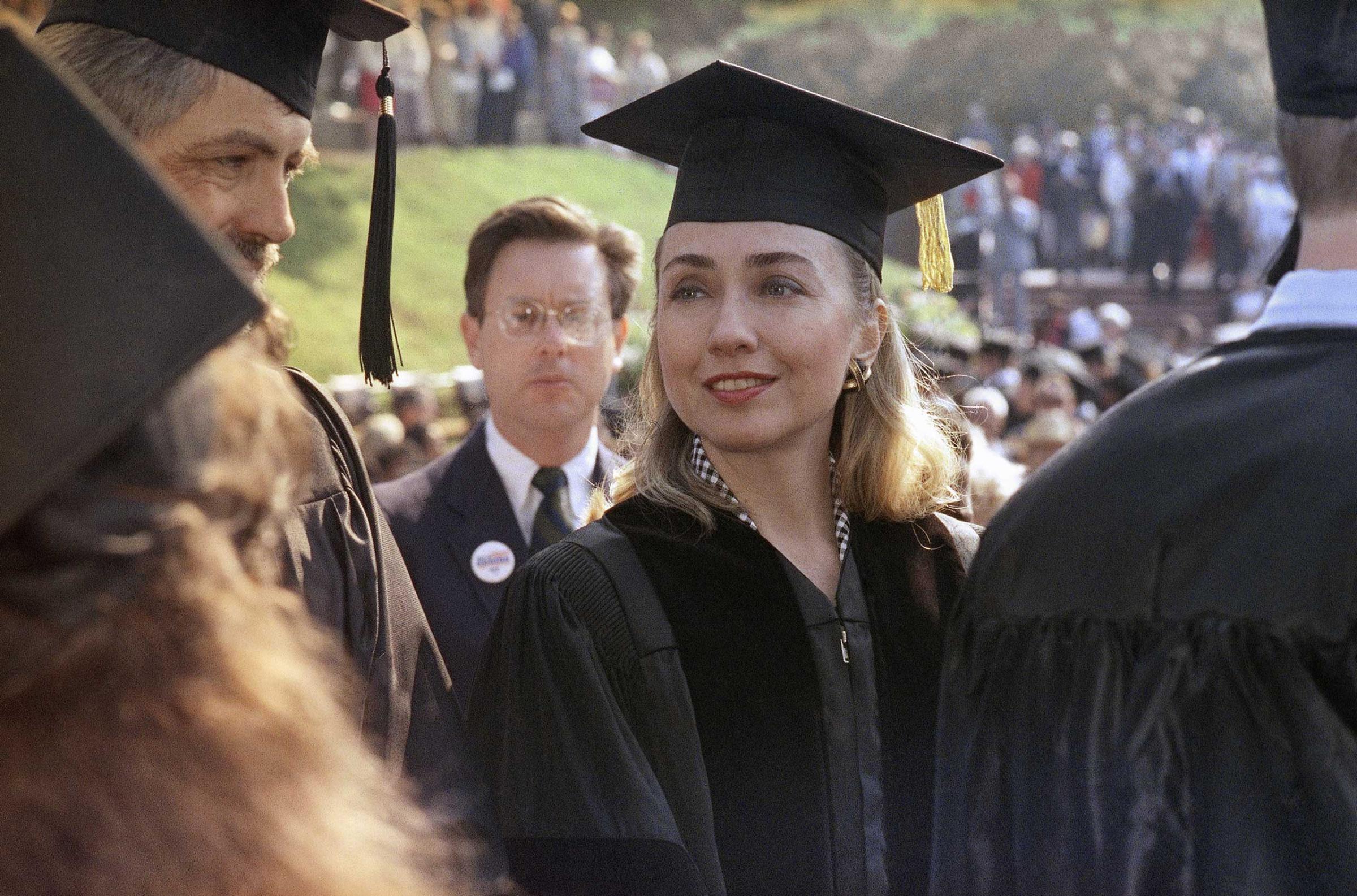

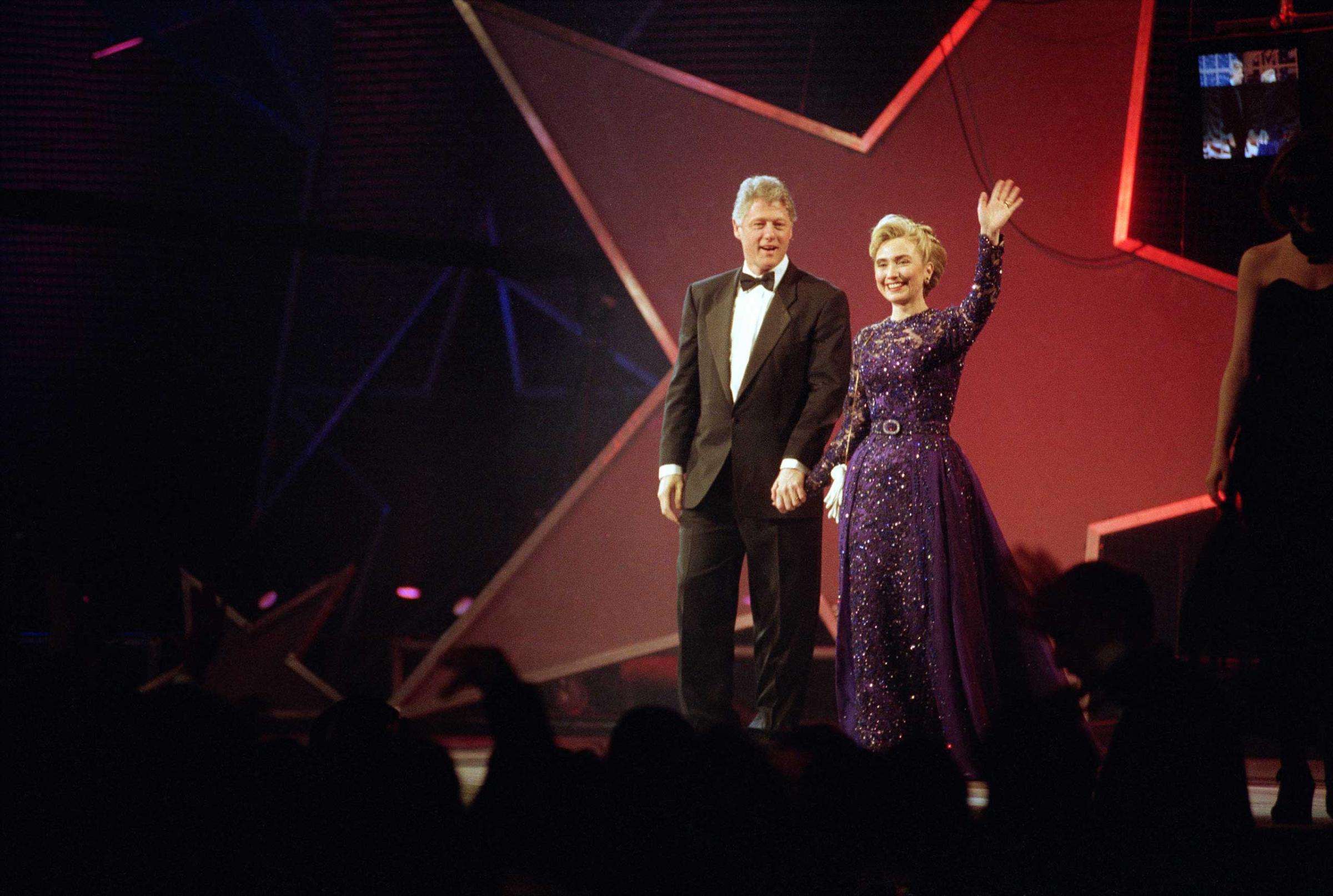

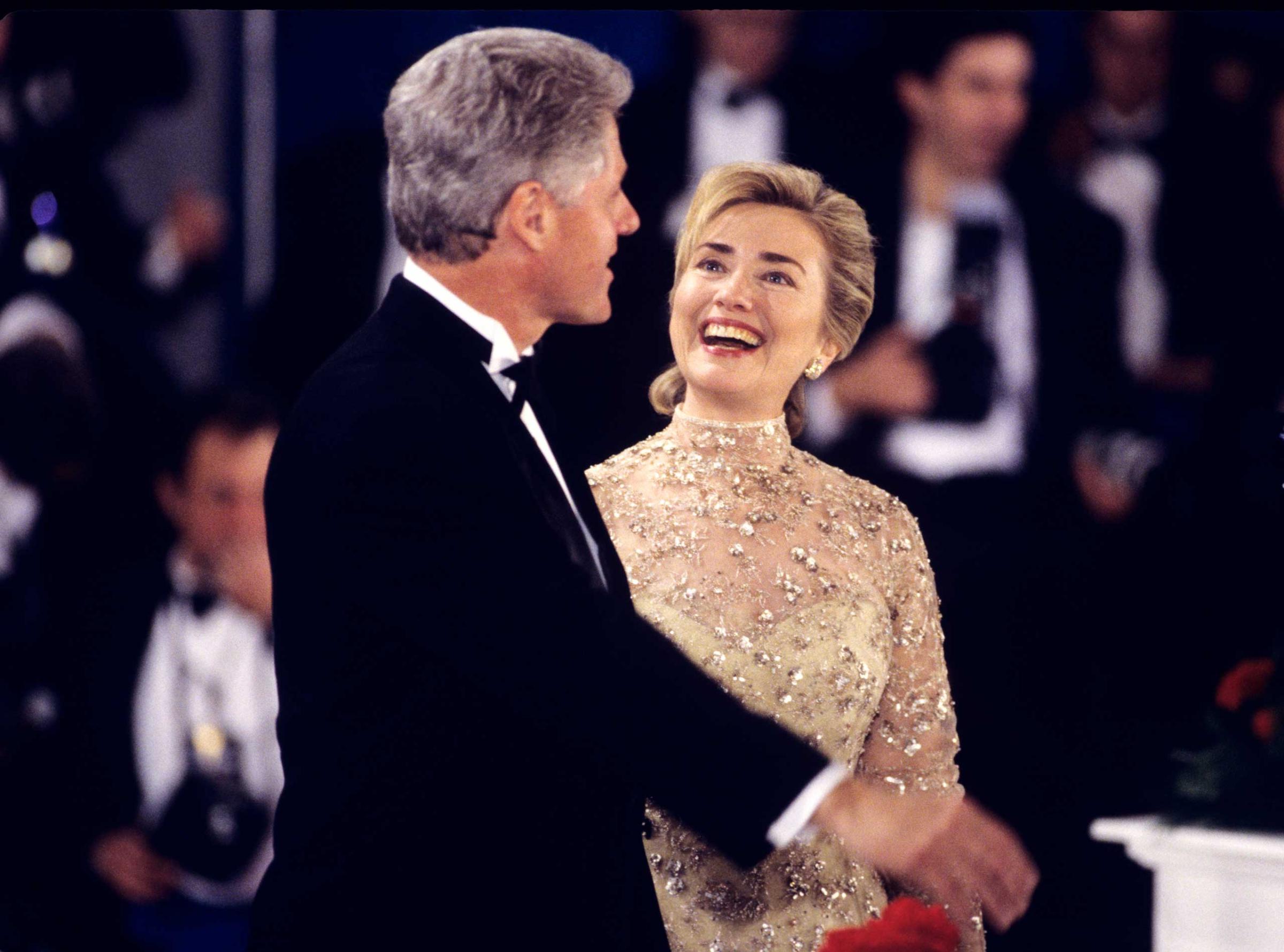

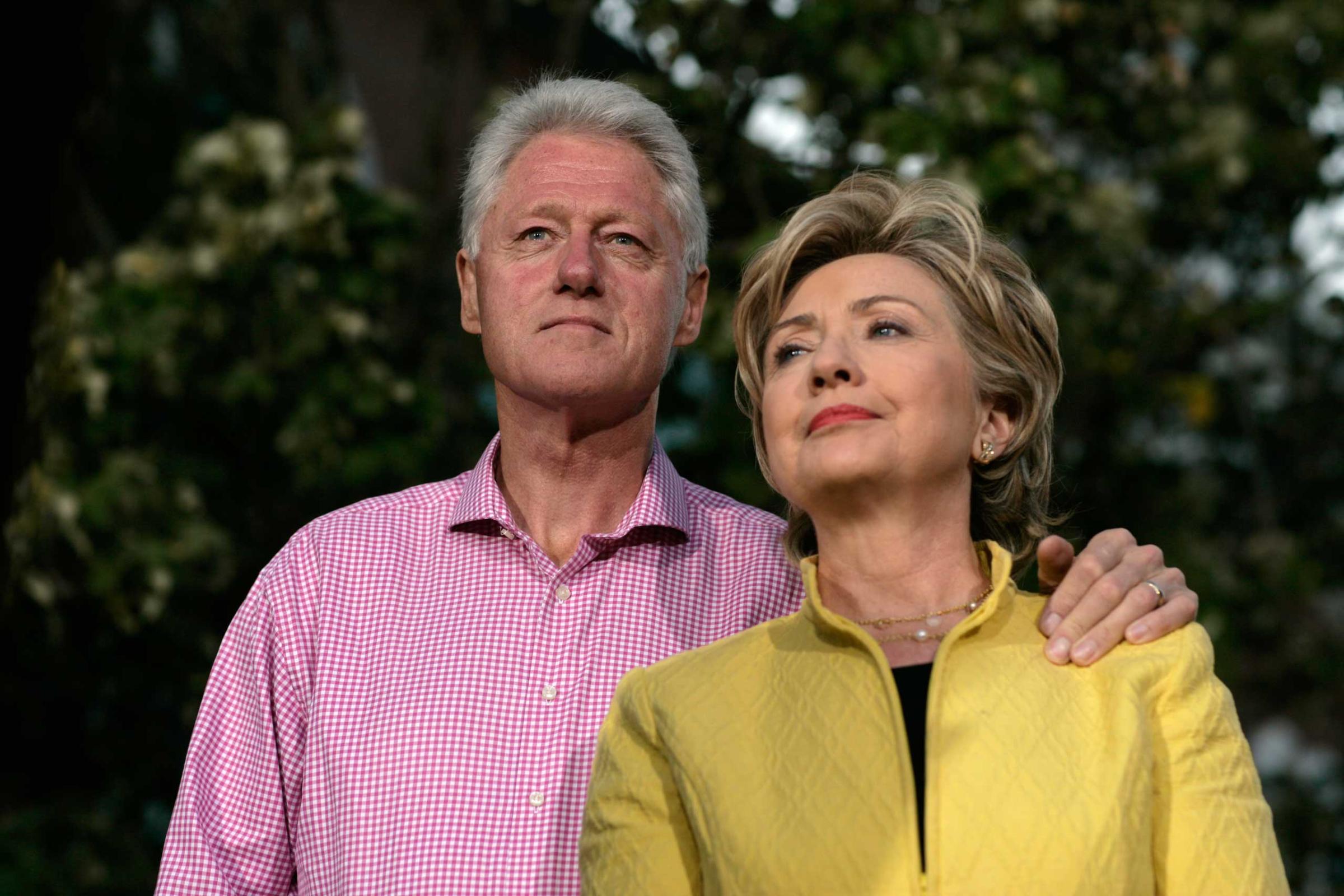

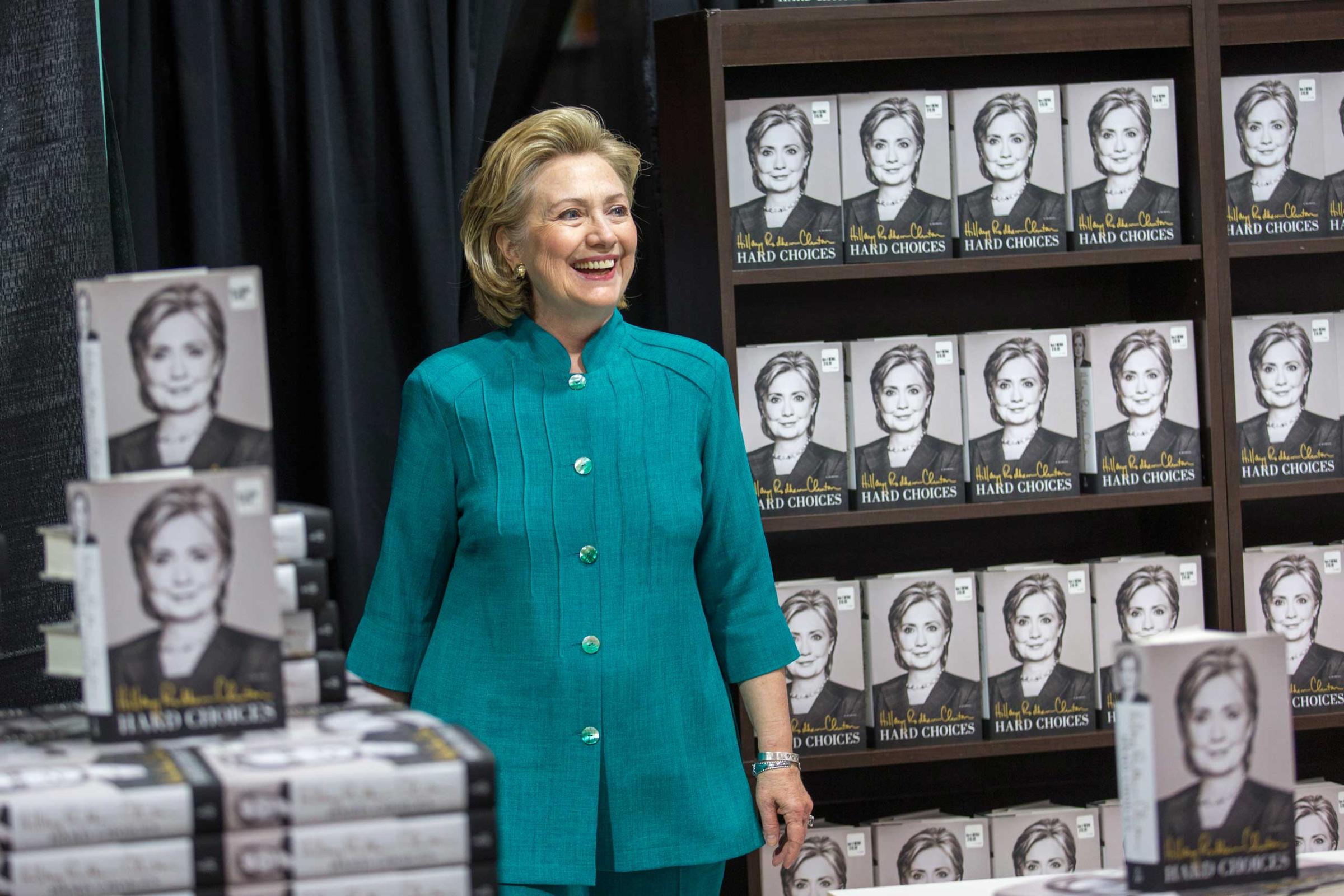

See Hillary Clinton's Evolution in 20 Photos

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com