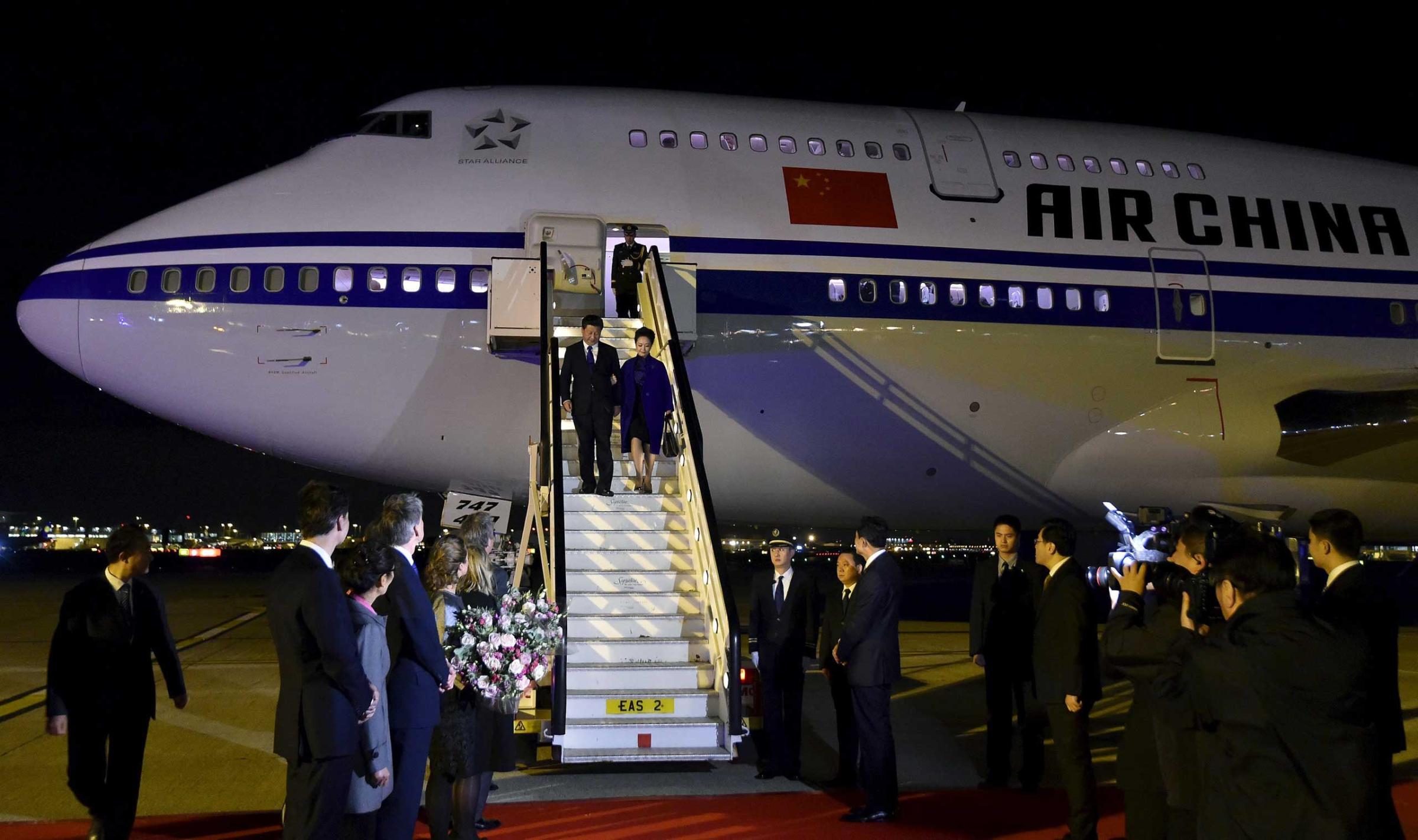

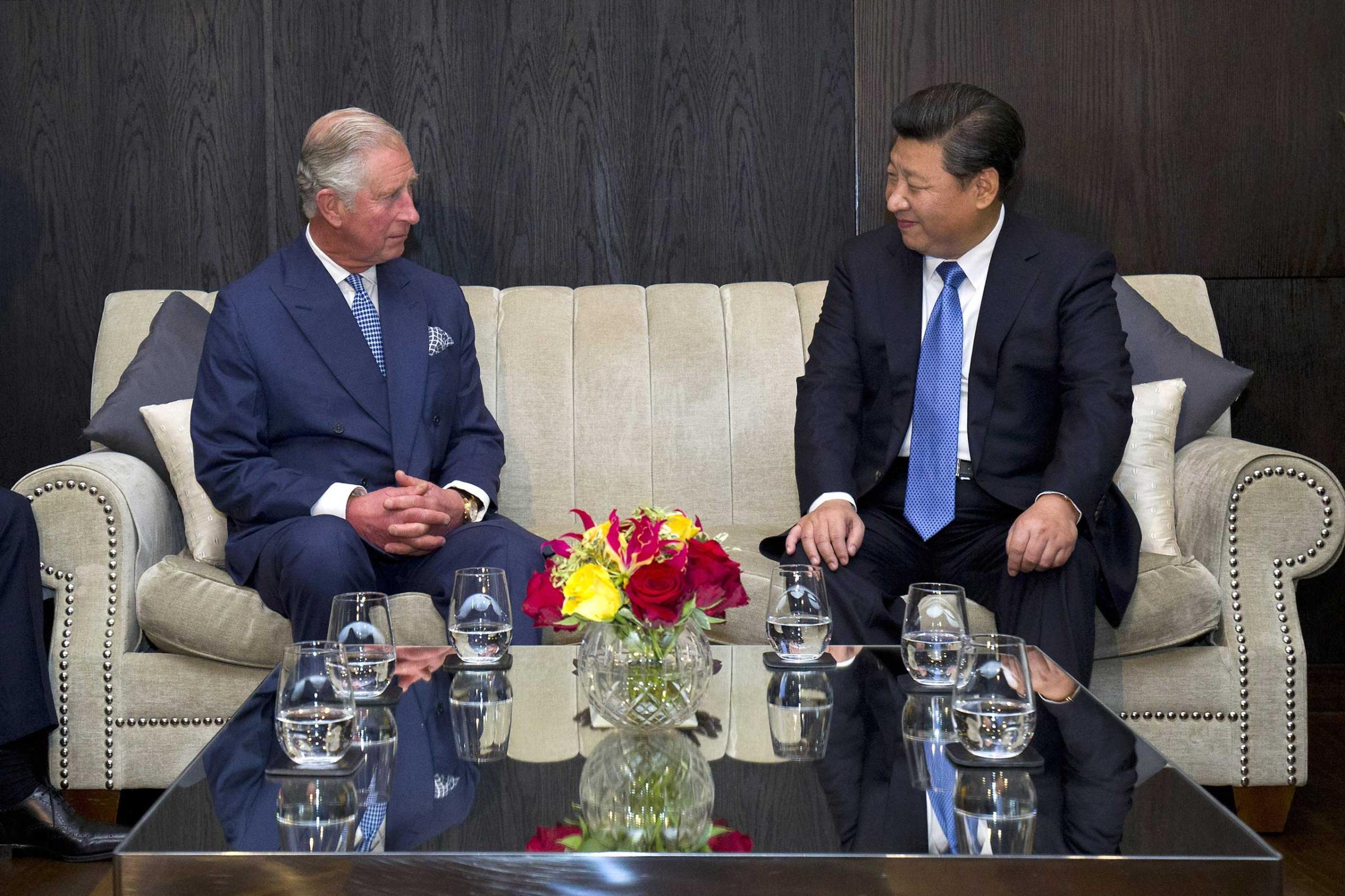

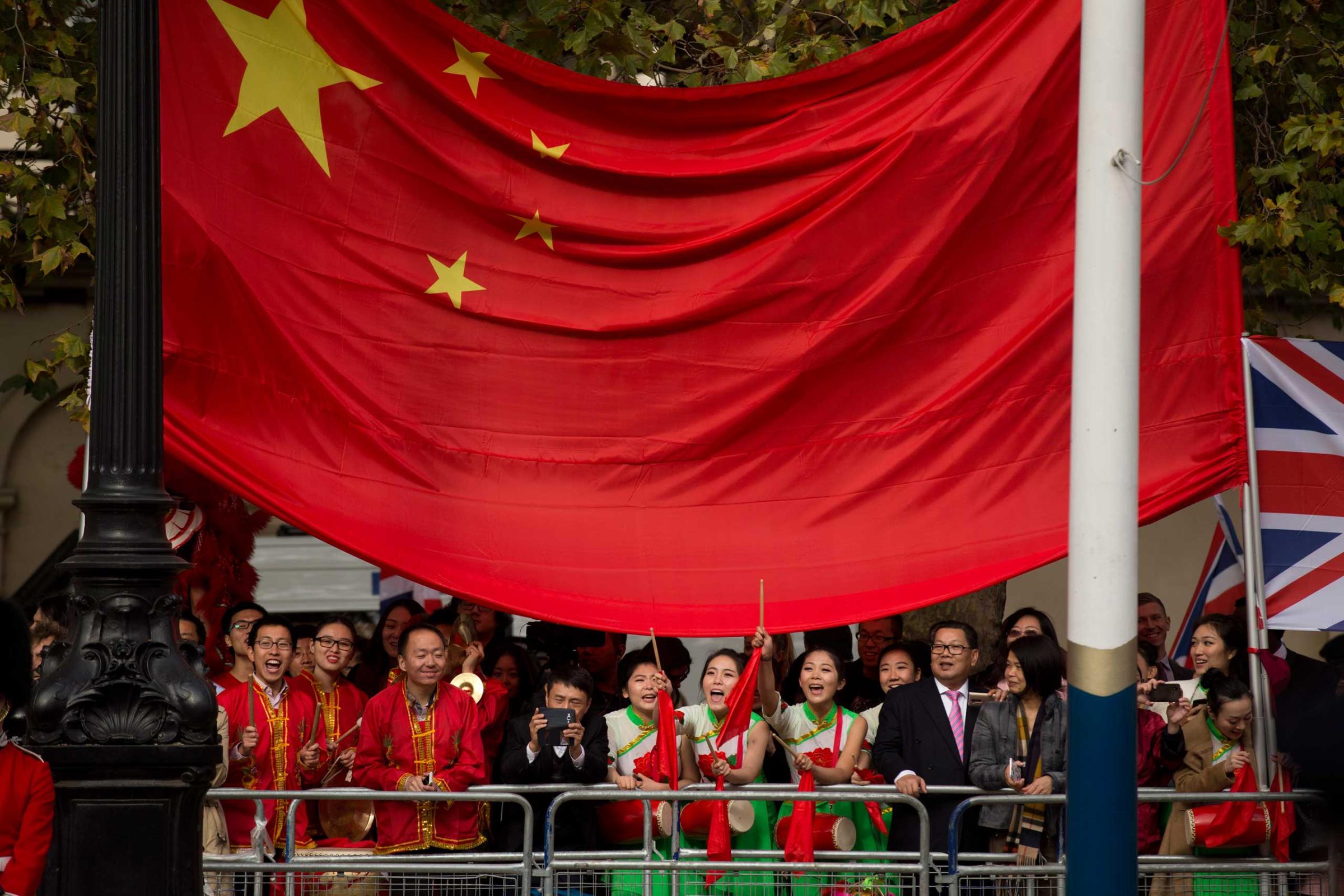

The sound of trumpets and hooves echoed through the park beside Buckingham Palace on Tuesday morning, as hundreds of guards on horseback rode in a procession to welcome the Chinese President Xi Jinping to London for a state visit this week.

The splendid welcome is a reflection of Britain’s recent, rather overt, fawning over China in an attempt to build stronger economic relations, a move that has some Western allies wondering if Britain is becoming too close. Britain’s wooing of the Chinese is an unusual break from the West’s more standoffish approach, say experts, and it comes at a time of particular concern, as China cracks down on domestic access to the Internet, and tussles with the U.S. over cyber attacks on U.S. companies and aggressive movement in the South China Sea.

Britain’s overtures to the Chinese—led largely by George Osborne, Britain’s equivalent of a treasury secretary — started in earnest in March when Britain made a point of becoming the first Western country and only member of the G-7, to join the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, China’s rival to the Washington-based World Bank. The AIIB is an example of China’s desire to establish a new set of world economic institutions to shift power away from the US. Britain’s joining of the bank caused tension with the US, as well as with other Western allies like Germany and France, that would have preferred to join the bank in a united front. European countries are eager for China to invest capital in infrastructure projects, which the Europeans see as an opportunity to boost their sluggish economies. For Britain’s part, Osborne has encouraged China to invest in building things like homes and high speed rail, in efforts to re-invigorate the Northern cities of Manchester and Leeds.

Though Britain is not alone in desiring Chinese capital, experts say it is unusual for a Western country to be so unreserved about the courtship. In September, Osborne travelled to China and declared Britain “China’s best partner” in the West, and called for a “golden era,” between the two countries. “It is probably the most comprehensive push by any Western country on commercial ties with China, at the expense of any of the other considerations,” says Andrew Small, a transatlantic fellow in the Asia program at the German Marshall Fund in Washington.

This week at the state visit, it seems as though Britain’s overtures are paying off. More than $46 billion worth of investment deals are expected to be announced between the U.K. and China during the four-day visit, according to the BBC, including an investment in a nuclear power plant in Southwestern England. The Chinese will provide 30% of the funding to the plant, which will be built by a French energy company and a Chinese state-owned energy firm. Construction and management of the plant will create thousands of jobs and it is expected to provide 7% of the U.K.’s energy needs when it is completed.

But experts warn that Britain’s courtship with China may not provide economic benefit with the effort and risk. For starters, they argue that Britain would have gained the same economic benefits with a more stand-offish attitude, particularly because China has always been more motivated by economics than politics. “China bases its decisions on rational considerations about what is best for China. It does not hand out benefits because someone behaves nicely or makes grandiose compliments,” says Volker Stanzel, a former German Ambassador to China, and fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. “I’m ready to place a bet on the theory that nothing in any major way will come London’s way that wouldn’t have come anyway based on Britain’s strengths.” Then, there’s also the possibility that Britain’s diplomacy may backfire. “There is also ironically a potential loss of influence of leverage with China. I don’t think the Chinese respect this kind of behavior, and in fact they regard it with some contempt,” says Aaron Friedberg, a professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton University.

The more obvious risk is that Britain may weaken the negotiating power of the entire West when trying to get leverage with China over issues ranging from cyber attacks on their firms to domestic human rights issues. “The Brits are contributing to something that could come back to haunt them,” says Friedberg. ” There’s a race to the bottom as all Europeans are courting the Chinese. The British have set in motion a real scramble on the part of governments in Europe to get access to Chinese markets and capital. This is going to result in a collective loss of influence on issues like human rights. When the Chinese are behaving badly in a number of different domains—cyber, cracking down on dissent, tightening control of Internet— there is much less chance of convincing them that they need to moderate their policies if countries like Britain are chasing after them. In the long run, it is a threat to the rule-based international order, which presumably we all benefit from.”

The Chinese have become increasingly difficult to contend with on a range of different issues, including their reclamation of land in the South China Sea, which has laid ground for military tension with the U.S. If it ever led to a larger conflict between the two powers, experts say, Britain’s allegiance to the Chinese could force it to choose sides. On the economic side, China’s dumping of its steel surplus in the European and U.S. markets have lowered the price worldwide, causing job in the U.K. and elsewhere— the kind of policy that the West can more easily challenge as a group. China has always seen the benefit in separating the Western powers, and in announcing a special relationship with China apart from the EU, say experts, Britain has given China exactly what it wants, and created problems for its allies. Says Friedberg: “As China gets bigger and stronger, we must all hang together,”

See Photos of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s State Visit to the United Kingdom

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com