Ramkaji Thami flashes a nervous look when talking about the coming winter. At 1,800 m above sea level, Suspa village is already chilly in mid-October. November, December, January: they’re painful to consider.

“Right now, we have firewood and maybe some clothes. It’s too high up here, though, so it’s not enough,” he tells TIME. “All the things are expensive now. The vehicles are more crowded, the price is high, the clothes are expensive. I thought I could open a livestock shop, but with the petrol shortage and the price of transport, it’s too much now.”

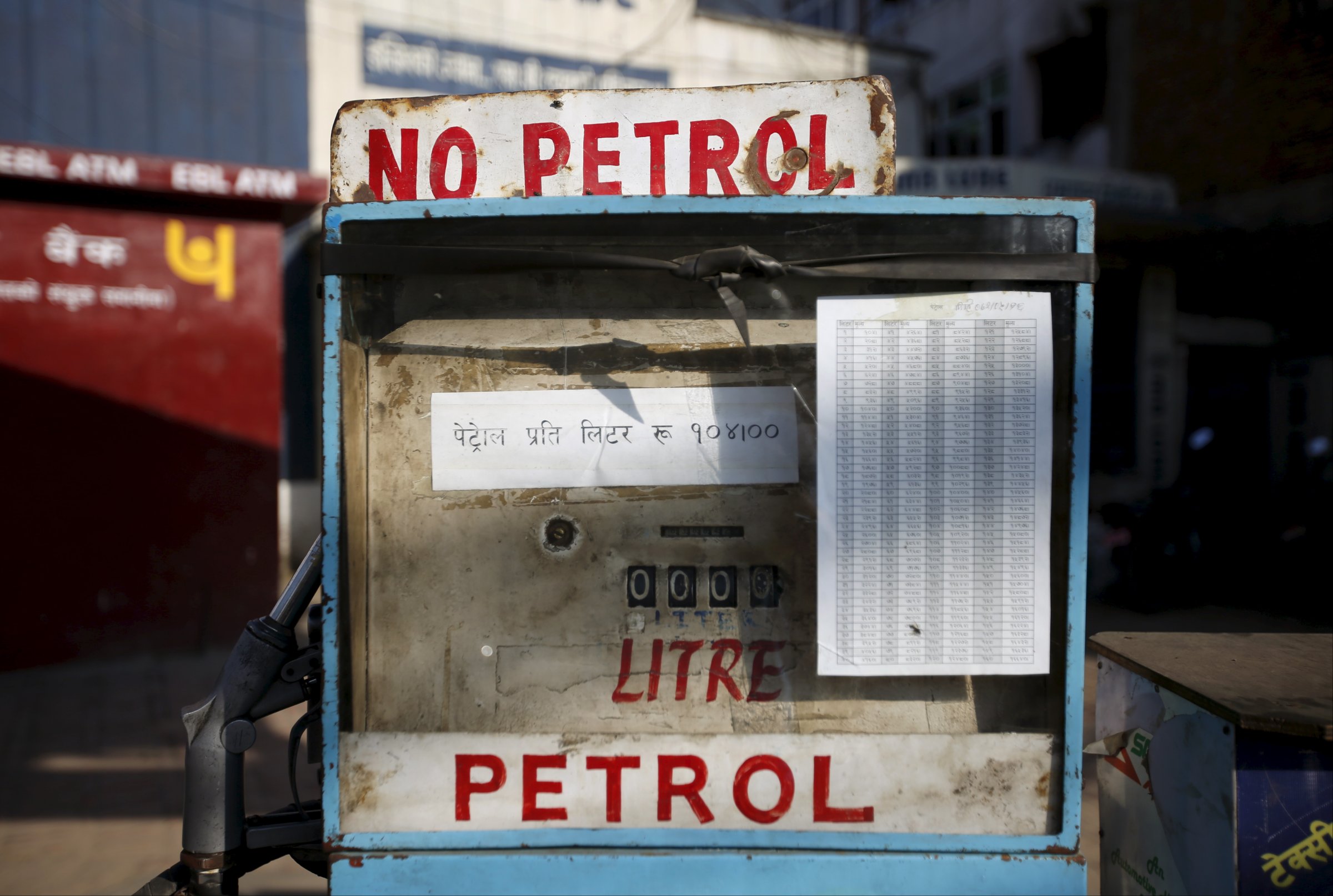

Across Nepal, a three-week-long fuel crisis has seen the price of basic goods and services soar. Though political leaders and citizens alike debate endlessly about who is to blame, the outlines are clear enough.

On Sept. 16, Nepal passed a long-awaited constitution containing several controversial clauses. Chief among these was a refusal to allow for Madhesi- and Tharu-majority provinces near the Indian border. While supporters insisted such a move was necessary to counteract Indian dominance, ethnic Tharus and Madhesis termed it a form of prejudice. Protests began in August and have been, at times, violent, reportedly claiming more than 40 lives. Citing security concerns, India launched an unofficial border blockade shortly after the constitution was enacted. While many here believe the blockade is an expression of India’s disapproval of the constitution, New Delhi has steadfastly denied political interference. “The reported obstructions are due to unrest, protests and demonstrations on the Nepalese side, by sections of their population,” said a statement issued on the Indian Foreign Ministry website on Sept. 25.

Regardless of intention, the impact has been substantial. In early October, Nepal’s scant reserves neared exhaustion and the government was forced to introduce fuel rationing. Since then, the effects have spread to every sector. At local markets, food prices have gone up — 30%, 50%, 100%. Restaurants are raising prices and scaling back production and, even in the capital city of Kathmandu, homeowners have begun switching from propane to firewood. Buses are severely overloaded, private transport uncomfortably expensive. Getting petrol requires waiting for hours, or even days, on queue for the government ration or paying black market rates out of reach for most Nepalese. Ambulances don’t have enough petrol to operate, hospitals are running out of supplies, social services severely curtailed.

Ganesh Bajagi, a tour operator in Kathmandu, says he has been buying fuel on the black market at six times the normal price. An incoming shipment of 10 L would be split with his brother, a policeman.

“He’s a policeman, but even he can’t get petrol,” Bajagi says with a shrug.

But it is in remote areas like Suspa where the pinch is particularly painful.

Like most people in Dolakha district — the epicenter of Nepal’s devastating April 25 earthquake — Thami lives in a spartan temporary shelter. More than 8,600 people were killed by the April quake and a second one that hit the following month, and hundreds of thousands were displaced. In Dolakha, 90% of the homes were destroyed.

As winter approaches, millions living in temporary housing are struggling to ensure their homes are warm enough. That would be no easy task in the best of times — most of the shelters are made of corrugated iron and tarps, materials that trap heat in the hot weather and grow frosty when it’s cool. But with transportation virtually shut down because of the fuel crisis, weatherproofing has become nearly impossible. Aid agencies carrying out “winterization” programs have been similarly stymied.

On Friday, the U.N. Humanitarian Coordinator warned that Nepal’s aid agencies had just weeks left to deliver aid to high-altitude areas before they would be cut off by snow. “Acute shortages in fuel supplies continue to impede planned deliveries to affected villages and trailheads,” the office said in a statement.

Ninh Nguyen, Plan International Nepal’s field area manager in Dolakha, says the impact has been considerable. “We have to suspend most of our work. Our car is on hold for emergency cases, there is no supply transport and no materials. Most of the work was supposed to be completed by the monsoon season but we can’t move our materials from India, so now we have 5,000 families still waiting for shelter.”

Govind Raj Pokharel, vice chairman of the government’s National Planning Commission, admits the fuel crisis “has had a huge impact on the reconstruction.”

“Because of not having enough fuel supply and not managing this political issue, we are behind three or four months for getting out material,” he says.

Back in the villages, rising prices have left their mark.

“There are blankets, sweaters, mittens in the market, but right now we don’t have enough money to buy them. Earlier, a blanket might be 900 to 1,200 rupees [$8.7 to $11.6], now it’s 2,000 to 2,400 [$19.3 to $23.1],” said Jiten Thami, who lives in the same displacement camp as Thami. “We are feeling so cold.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com