The 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration clearly stated that Hong Kong could remain unchanged for 50 years after China resumed sovereignty in 1997. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) also promised — in Hong Kong’s miniconstitution known as the Basic Law — that Hong Kong’s leader, or chief executive, could be chosen “by universal suffrage.” This meant that Hong Kong, an international metropolis, proud of its freedoms and openness, could be part of China but run separately under the principle of “one country, two systems.” Hong Kong could enjoy rights that came from the maintenance of its core values of judicial independence and separation of powers, as well as the implementation of universal suffrage after the handover in 1997, working finally toward the ultimate aim of democratic self-governance.

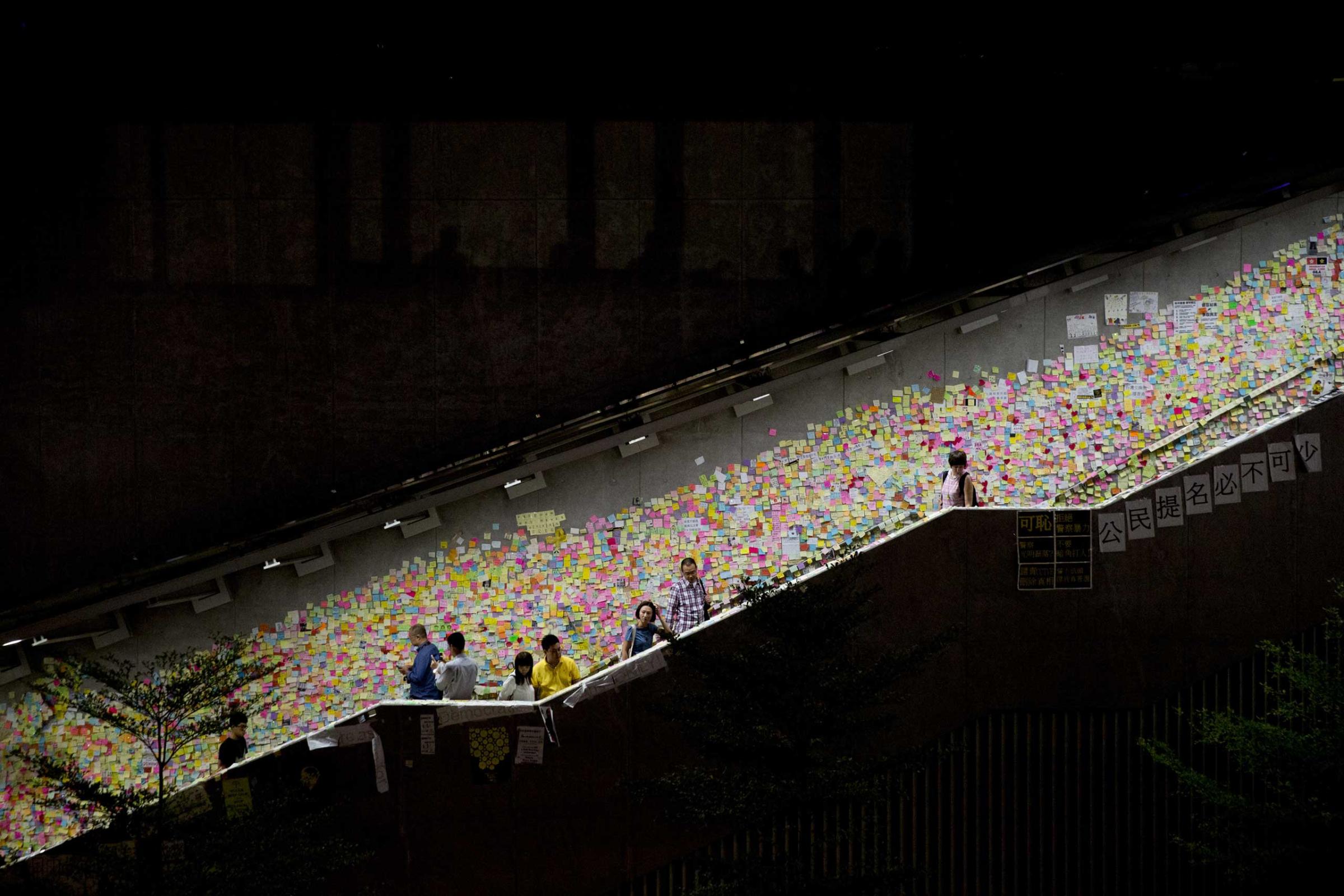

Regrettably, even though the people of Hong Kong have held lawful rallies, as well as a mass referendum, with the mobilization of up to 500,000 and 800,000 participants respectively, their urgent plea for the enactment of universal suffrage has not been given a green light by the CCP over the past 18 years. To the contrary, on Aug. 31, 2014, China’s National People’s Congress set forth its decision that only political figures who love both the country and the party could be candidates for position of chief executive of Hong Kong; in the same year, it presented a white paper underscoring President Xi Jinping’s theory of a collaboration between the legislature, executive and judiciary, threatening Hong Kong’s spirit of high autonomy and separation of powers. This finally prompted street occupations by up to 200,000 demonstrators. On Sept. 28, 2014, fearless protesters staged a mass demonstration of civil disobedience in the face of tear gas — the outbreak of the 79-day Occupy Hong Kong Movement, also known as the Umbrella Movement.

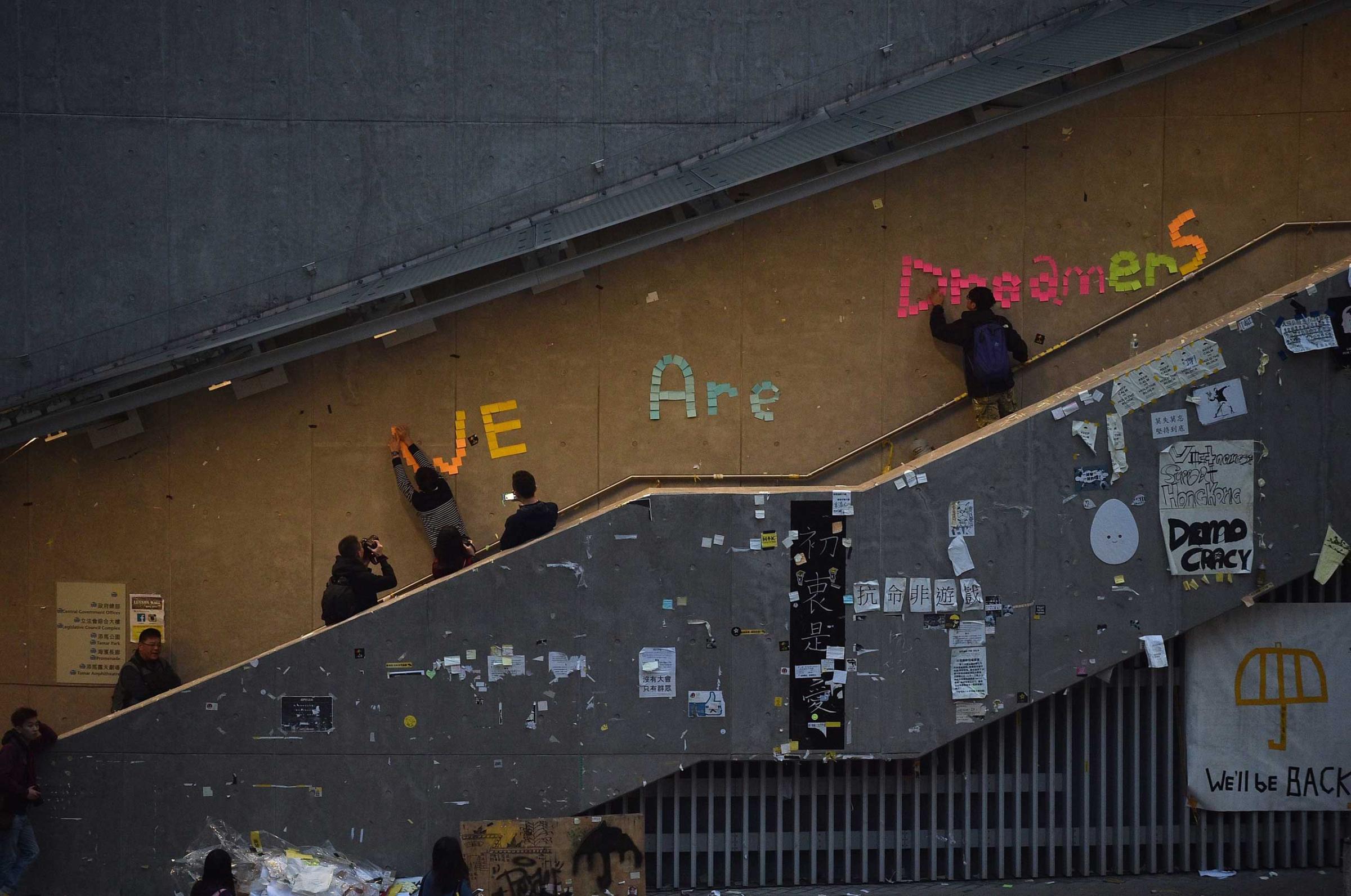

Yet, the protests last year soon proved a failure in even obtaining a single concession from the CCP. It was completely upsetting for the younger generation to learn that even such a massive mobilization as the Umbrella Movement could not bring democracy to Hong Kong. We had thought that China’s rise would bring open-mindedness to its leaders, and spur democracy in the mainland, allowing China to catch up with Hong Kong’s democratic development by the year 2047, when Hong Kong’s 50 years of no change ends. We now look back and realize that all this is merely a fantasy, and that the struggle for universal suffrage is futile under the framework of “one country, two systems.” That exists in name only.

Moreover, both the Chinese and the English governments never promised the continuation of “one country, two systems” in Hong Kong after 2047. The CCP could turn “one country, two systems” into “one country, one system” in 32 years’ time, meaning it is possible that Hong Kong will not be a special administrative region, as it is now, but instead a “mainlandized” municipality directly under the jurisdiction of China. Even if the CCP is willing to stick with “one country, two systems” in principle, no one can say for certain whether Hong Kong’s freedoms of speech and the press would survive in reality. The dream of maintaining Hong Kong’s core values after 2047 is simply nonsensical.

Because of this, Hong Kongers should not only focus on universal suffrage, but also fight for the city’s right to self-determination. We should, through civic referendums, determine our own pathways and political status after 2047, because in this lies the future of our democratic movement. If Hong Kong could exercise democratic self-governance under the sovereignty of China, it would not be necessary for us to take this step on the path toward independence. But what self-determination guarantees us is a government of genuine public consent, no matter where Hong Kong’s path may have taken it by 2047; it will safeguard and protect the city’s democracy and autonomy.

Precisely one year ago, the Umbrella Movement was launched. Students occupied the streets and, on the same day, I was arrested for the first time. Although no fruits were gained from these protests, Hong Kongers do not have to feel discouraged and downhearted. This is because our struggle with the CCP for democratic self-governance has always been a battle of longevity.

Democratic politicians of the generation before mine are yet to address the question of self-determination. However, the young generation must realize the truth and understand this hard-to-achieve ideal. This includes maintaining the basis of democratic rule in Hong Kong and launching a movement for self-determination before the expiration of the “one country, two systems” policy; it also involves getting a consensus from both the local and international community that Hong Kongers shall have the right to determine their city’s future, as well as bringing a new generation’s call for self-determination into the political arena, replacing Hong Kong’s present gerontocracy. If we can do this, we might have a slight chance for our ultimate goal: democracy and autonomy.

In face of the CCP Goliath, I am optimistic that David can triumph. All we need is time and determination.

Student and activist Joshua Wong was one of the core leaders of the 2014 Hong Kong street occupations, which saw protesters take to the streets for nearly 80 days in a largely peaceful call for full democracy. That year, he was named one of TIME’s 25 Most Influential Teens.

Translated from the Chinese by Melody Andrea Chuh.

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com