Developing a long-term documentary project requires a combination of dedication, time, and funding. Without all three, completing a polished product is nearly impossible. But finding ways to fund these projects over the years has become difficult, especially in a market where editorial assignments are in decline.

TIME LightBox selected five of the most successful documentary projects and spoke with the photographers asking them how they funded their work.

Eugene Richards—Red Ball of a Sun Slipping

Eugene first went to the Arkansas Delta as a volunteer in 1969, where he opened a community service organization and newspaper and spent four years documenting poverty and prejudice in the area. Forty years later, National Geographic sent him back to shoot a follow-up project.

He combined the two bodies of work into a book but found that all of the publishers wanted him to front the cost of printing. Instead, his son suggested he try a Kickstarter campaign. 485 backers later he had almost $69,000 and was able to publish his book and also produce a series of exhibitions, and donate hundreds of copies to libraries and cultural institutions.

Richards’ Advice: “Kickstarter is a good avenue because it’s democratized. Strong projects get funded rather than just big names. It’s marketing a project rather than asking for donations (the project’s funders were made up almost entirely of people he did not know). But don’t do it all on your own. The mechanics of getting the rewards out are complex. Finally, make a video that explains your project but don’t aggressively sell it to viewers. Don’t try to make yourself into what you are not.”

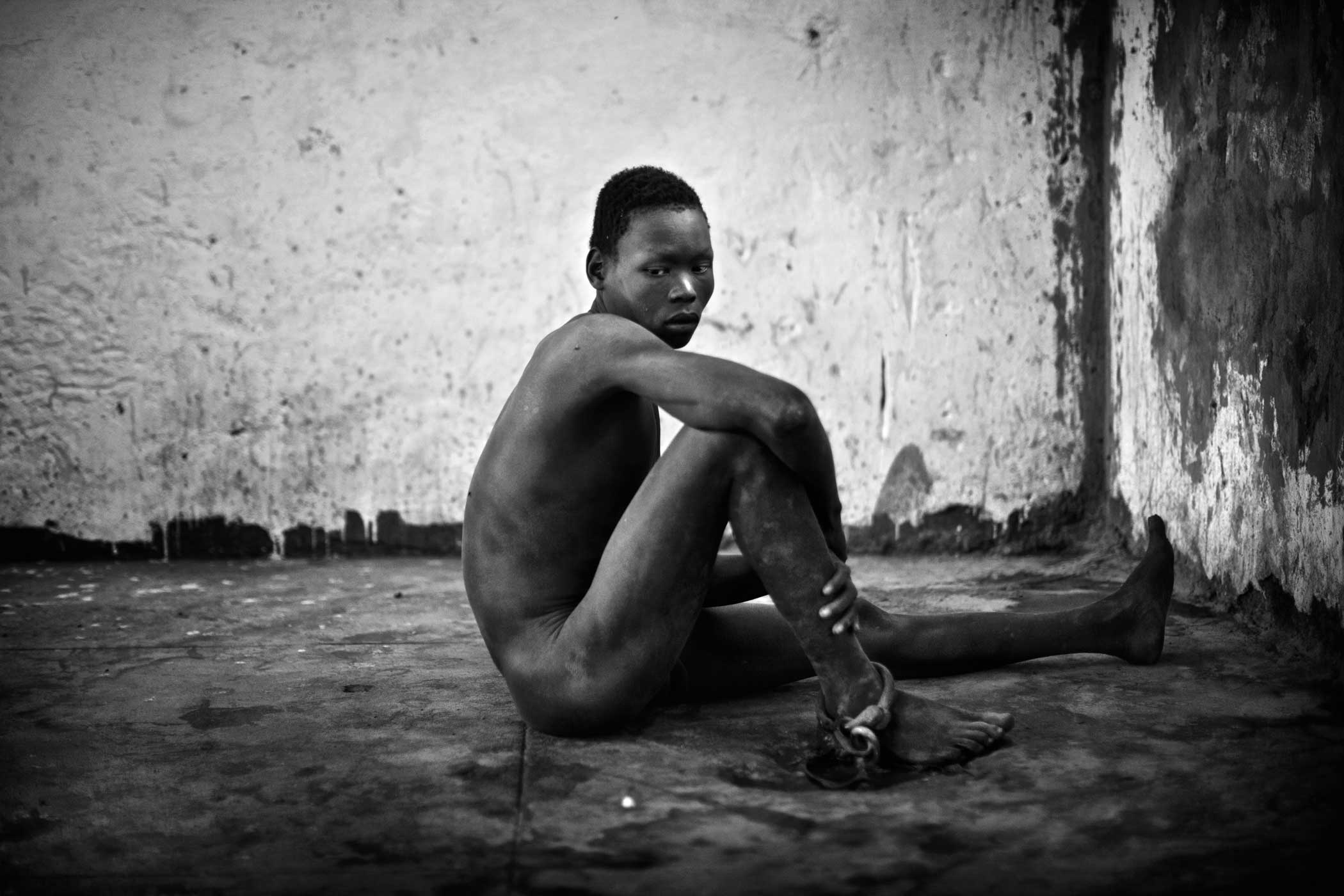

Robin Hammond—Mental Illness

To document the mental health impact of disasters in sub-Saharan Africa, Robin Hammond travelled to nine countries between 2011 and 2013. He spent time with the displaced in refugee camps and saw the impact of corruption on facilities for the mentally ill. In 2015, Hammond is continuing his project in Africa, Lebanon and eastern Ukraine.

Hammond used a wealth of sources to fund his work. From newspaper and NGO commissions to a crowdfunding campaign on Emphas.is. A large bulk of his work was made possible by a series of selective high profile grants from the Pulitzer Centre on Crisis Reporting, W. Eugene Smith Fund, and the Dr. Guislain Breaking the Chains of Stigma Award.

Hammond’s Advice: “Don’t wait for the money to begin your work. It is really hard for a funder to give you money based on an idea. They have to trust you with their money, which means they have to know you can pull it off. It is much easier if they can see a beginning of the project, or something very similar to it. If you do your work with integrity and are really passionate about it, others are likely to be passionate about it too and want to support you.”

Mitch Epstein—Family Business

Mitch Epstein returned home to photographed the last days of his father’s bankrupt furniture business and decaying rental properties as an approach to documenting the decline of Holyoke, Mass., a once prosperous industrial town.

To fund his work, Epstein employs approaches that are more common in the fine art world than in traditional photojournalism. Most of his work is self-funded and supplemented with income from print sales. He shows his work to a limited number of collectors who invest in good faith, with prints coming later. Epstein received a Guggenheim fellowship for the project, but has funded work through various jobs within the photo and video worlds including freelancing in an advertising studio, teaching classes, commissioned work, editorial assignments, and cinematography. Only recently has he been supporting his work through the sale of prints.

Epstein’s Advice: “It’s a harsh reality but the people that are going to find a way to navigate through that challenge are going to end up potentially making better work because they need to push through. I do my best work when I’m funding it myself. I don’t have to worry about anyone else’s agenda.”

Kadir Van Lohuizen—Via PanAm

In 2011, Kadir Van Lohuizen embarked on a journey to cover migration in the Americas, continents he felt were shaped by colonialism and migration. He wanted to explore why people migrate and the geopolitical, economic, and environmental impacts it has. Van Lohuizen spent 40 weeks traveling through 15 countries primarily on the Pan-American Highway. His 15,000 mile trip started in Tierra del Fuego, the southern tip of Chile and ended in Prudhoe Bay, northern Alaska.

Unable to secure funding, Van Lohuizen learned about the release of the iPad shortly before the trip kicked off. He built one of the first apps for the device and released Via PanAm on it. Van Lohuizen reflected that “sometimes the packaging is more important than the content”. Utilizing a new platform helped secure funding from the Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design and Architecture and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands. Eventually it led to support from backers like Emphas.is and IS Magazine, Nikon World, and many others.

Van Lohuizen’s advice: “If you really believe you’re onto a great story stick with it. Please do your research. Don’t try to adjust your project because you think the market needs something else, because in a year the market will change again. If you find a new angle you will still succeed.”

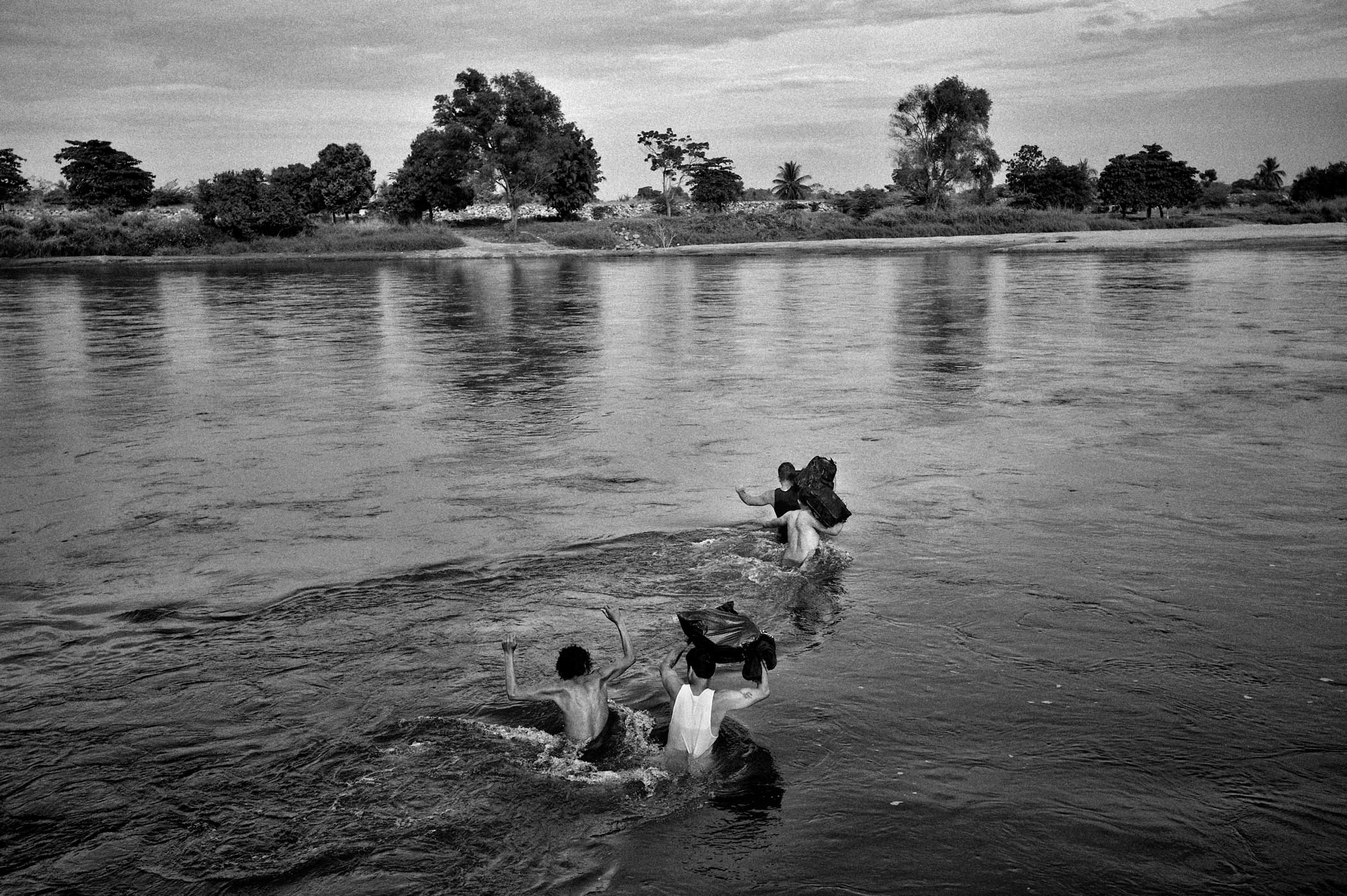

Kirsten Luce—Crossing the Valley: Migration’s Long Shadow

For almost a decade, Kirsten Luce has been documenting immigration and law enforcement in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, first as a staff photographer at The Monitor in the border town of McAllen, Texas, then as a freelance photographer.

Since 2012, she has self-funded trips to the border and then licensed her work to publications to reimburse the costs. Her projects have appeared in the New York Times, Harper’s Bazaar, Newsweek, Bloomberg Businessweek, TIME Magazine, and here on Lightbox. Over the years, she has developed a deep understanding for the region and tries to approach editors with pieces that are timely, relevant for their readers and ready to publish.

Luce’s Advice: “Select a story where you can keep your costs relatively low and which isn’t inundated with other photographers. Ask for appropriate compensation when licensing your stories. If a publication approaches you with interest for your project, you must consider the time and costs you’ve invested when negotiating. Finally, pick a subject that moves you personally. If you are going to invest your time and energy, you’ve got to firmly believe in its significance.”

Josh Raab is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com