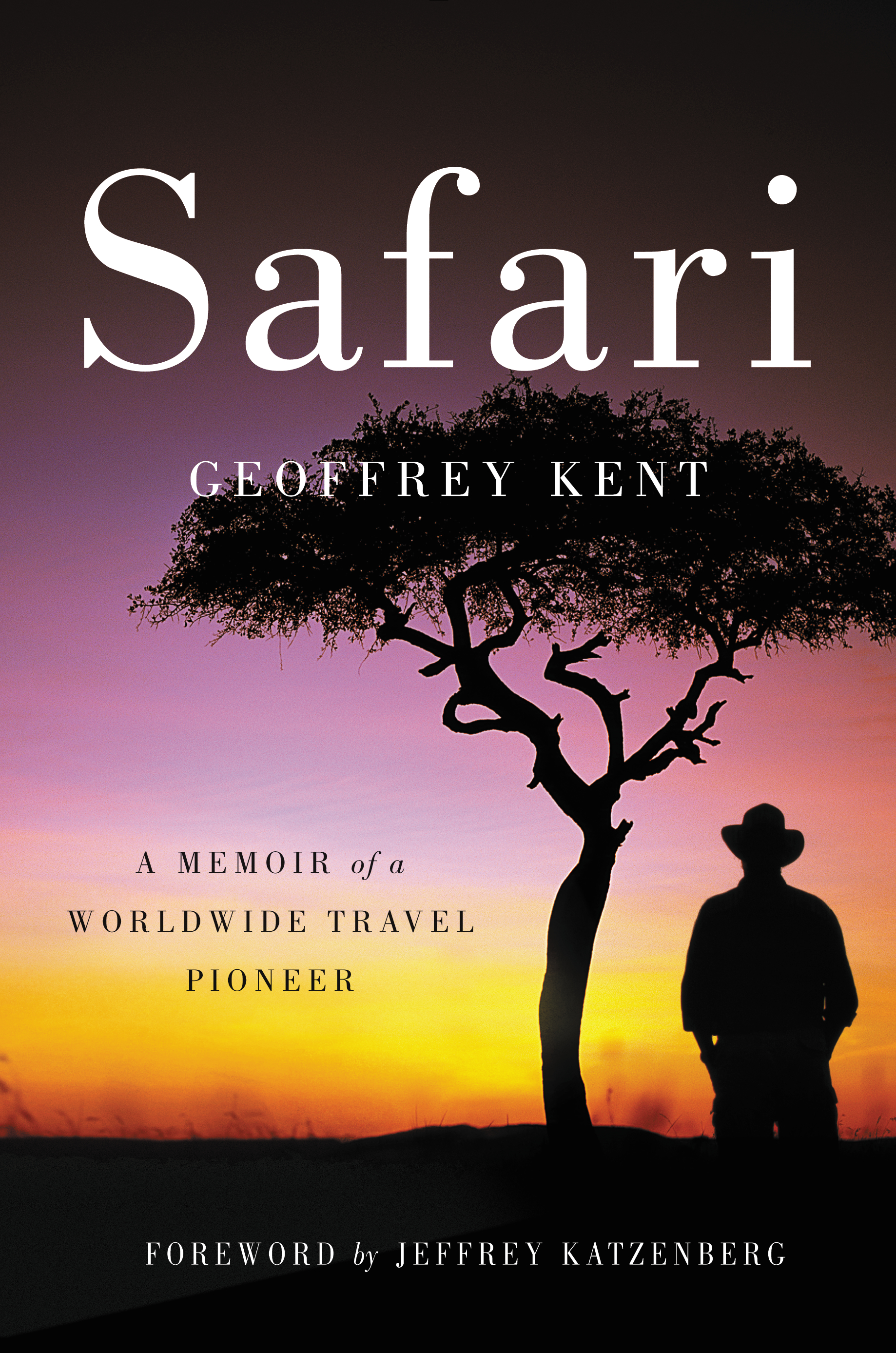

Geoffrey Kent’s origin story dovetails perfectly with his career: the co-founder and CEO of luxury travel company Abercrombie & Kent was born while his British parents were on safari. Kent spent his childhood in Kenya, founding his safari outfit with his parents in 1962. The company, which has always espoused a no-hunting agenda, pioneered glamping with conveniences like mobile refrigeration, and the job took Kent around the world. His new book, Safari: A Memoir of a Worldwide Travel Pioneer, will be released next week, with a foreword from Jeffrey Katzenberg, the CEO of DreamWorks and an Abercrombie & Kent client. Here, Kent discusses endangered species, the perils of poaching and the death of Cecil the lion.

TIME: What did you think when you heard about the killing of Cecil the lion?

Kent: I was appalled and actually quite disgusted by the whole thing. It was really a dreadful thing to have happened. I had a deep feeling of revulsion.

What should have been done to prevent this?

Obviously you should have far tighter control. When you have professional safari hunting companies, they should be heavily regulated by the government, and the government’s got to make sure that the professional hunters, the people who take the clients hunting, should also have a long period of training like they used to back in the ‘60s. It took you seven years to be trained as a professional hunter. The code of ethics were very strict, like the code of ethics of a lawyer. Today I don’t believe that that is there anymore, and so I think that you’ve got to bring back professional training of professional hunters where the code of ethics is bred into their DNA from day one and tightly policed by the government. Obviously I’m not a lawyer and I’m not a prosecutor, but whatever happens, it should stop forever any animal being lured out of a national park by meat or whatever to be poached and killed in cold blood. That’s got to stop.

What do you think of the ban on bringing big game trophies on certain major airlines?

I applaud it. I feel that actually this incident of Cecil is becoming a lightning rod of pulling everybody together in this whole subject of shooting wild animals.

How do you think tourists should approach visiting animals in their natural habitats?

In the world today, you have professional hunters and you have tourists, and the two are not even on the same table. We, Abercrombie & Kent, handle tourists and travelers. And that is why I, years back, came up with the slogan “Hunt with a camera, not with a gun,” and invented the first non-hunting safaris using all the tented camps that hunting safaris used. Maybe I’ve been a trailblazer in this. People should only come to look at wild animals and take photographs and not kill them.

What are the animals we should be most concerned about in Africa today?

I’m very concerned about all the animals, but I’m particularly concerned about the black rhinoceros and the white rhinoceros and obviously the elephant. If we go on like we are with the poaching of the rhino, they will be extinct within 10 years, and I don’t think I’m an alarmist by saying this. We have to do everything possible within our powers to stop the poaching of wild animals.

We’re bringing a lot of the black rhino out of South Africa into Botswana, and that’s going on as we speak. Abercrombie & Kent Philanthropy has been working hand in hand with the people in Botswana to rehabituate and relocate these black rhino into Botswana. And that’s another way of trying to save the animals. In Botswana, there’s a massive large habitat available to rhinos, where there’s not in South Africa. And so you’re moving them into a habitat that can absorb them. And Botswana has very good policing of looking after animals, especially rhino.

How can we stop poaching?

First of all, we need the governments concerned to really say to themselves, do they actually need hunting to go on? Secondly, one has to really work out how this poaching is taking place: who is behind it? Where is it going? And everybody concerned, the consumer and the government, have to get on the same page. Ivory belongs to elephants. Ivory does not belong to us. We have to get that in the heads of people. The rhinos, too—there is no good quality of rhino horns. The fact that people say it can be used as an aphrodisiac is complete nonsense. As soon as the consumer understands there is no value to animal parts, that’s the first thing. Second thing is, governments have to police their own wildlife.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com