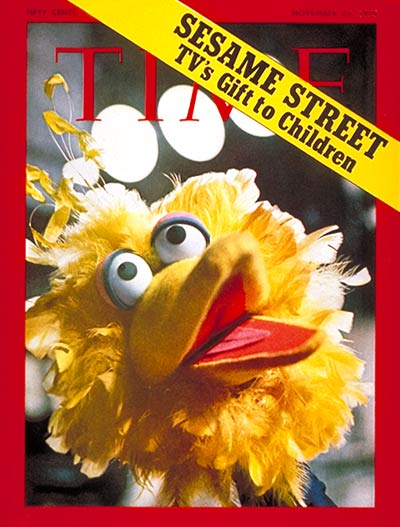

What is it about the long-time favorite television show, Sesame Street, that has allowed it to influence generations of viewers?

A recent study by economists Melissa Kearney and Phillip B Levine concluded that children who watched Sesame Street in the 1970s fared better in school than peers who did not tune in to the iconic program.

The study found that children who lived in areas with greater Sesame Street coverage in 1969 were significantly more likely to be at the age-appropriate grade level.

This effect was particularly pronounced among boys and black, non-Hispanic children. The study found that the likelihood of these children being left behind was reduced by 16% for boys across race and 13.7% for black, non-Hispanic children, in areas with strong reception.

Sesame Street’s magic

As an educational researcher, early childhood educator, psychologist, and dedicated Sesame Street viewer during my own childhood in the 70’s, I am well acquainted with the show’s power to influence children.

I have spent the last 15 years working with children growing up in the context of urban poverty. Presently, I am investigating the educational experiences of preschool-aged children who are homeless.

These experiences inform my perspective on why Sesame Street, in particular, has had such a positive impact on young viewers.

What I am concerned about is the conclusion of the authors of the Sesame Street program study that “TV and electronic media more generally can be leveraged to address income and racial gaps in children’s school readiness.”

Perhaps.

But we should proceed with caution in advocating blindly for an increased emphasis on children’s television and screen time as a potential remedy for America’s persistent achievement gap. And we must understand: why is it that Sesame Street has helped children learn all these years? For this, it is important to understand what makes Sesame Street such a powerful teaching tool.

First, Sesame Street is developmentally appropriate. Research on child development informs the show and concepts are presented in a way that is appropriate for young learners. Research shows when instruction is aligned with children’s capacity to understand it, they willingly engage the material and develop self-confidence.

Second, education trumps entertainment. On Sesame Street, children are engaged as partners in learning – they are asked to repeat, respond, and to think about what is occurring on the screen.

Third, Sesame Street honors children’s lives and engages them in discussions about things that matter to them, including diversity and difference. Children see people like them living and learning on Sesame Street.

Moreover, over the years, Sesame Street has not shied away from difficult topics such as death, homelessness, discrimination and incarceration.

As important is that Sesame Street helps children who have not experienced these things relate to them. This helps foster empathy for others. In short, Sesame Street relates to children and helps them feel as if they matter.

Screen time is not a remedy

However, increasingly, these crucial elements are being overlooked both in children’s classrooms and in media targeted at them.

Even though children are spending many more hours in front of the television than children did during the 1970s, there is much greater disparity in academic achievement and other indicators of learning.

The gap in standardized test scores between affluent and low-income students has grown about 40% since the 1960s and is now double the testing gap between white and black students. A separate study found that low-income boys who spend more than 5.5 hours per day using sedentary screen media are the lowest-performing students.

Learning has lost its fun for children. Young children are being asked to master content that is beyond their appropriate developmental level. This makes learning frustrating and leads children to feel insecure.

Frequently, screen time is used to entertain and/or manage children, shifting them into the role of passive observer. In my work as an educational researcher and clinician, I have found this is especially true for children whose behavior is viewed as challenging, who may be parked in front of a television or computer screen so that others might disengage from them.

Thus, children experiencing challenges in their personal lives are often not supported in developing coping skills.

In building on the findings of this recent study, it is important to keep in mind that Sesame Street made a difference because of its approach, not just because the television was used to deliver it.

Children are willing to tune into Sesame Street and pay attention because it is relevant. When learning occurs in a context that is relevant to children’s lives, they pay more attention and retain more information.

We should proceed with caution in advocating blindly for an increased emphasis on children’s television and screen time as a potential remedy for America’s persistent achievement gap.

Most of all, we must understand the magic that is Sesame Street in order to replicate its impact.

Travis Wright is Assistant Professor of Multicultural Education, Teacher Education, and Childhood Studies at University of Wisconsin-Madison.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com