The Beatles may have had reputations as laid-back peaceniks, but their former manager Allen Klein was known as a pitbull.

Klein made a name for himself in showbiz by auditing music labels’ financial records to make sure his clients weren’t getting shortchanged, and he usually retrieved funds for them in the process. It made him more than a few allies on the talent side, if not on the business side. His career took off in 1963 when Sam Cooke asked Klein to be his manager, and after acquiring the Rolling Stones as clients, he set his sights on the Beatles.

“No one wanted or needed to manage the Beatles as much as Allen did,” Fred Goodman writes in his biography Allen Klein: The Man Who Bailed Out the Beatles, Made the Stones, and Transformed Rock & Roll, out now. Though the manager was always looking for a creative new way to make a buck, Goodman writes, “he would have managed the Beatles for nothing. Klein saw handling them as final and irrefutable proof that he was the best.”

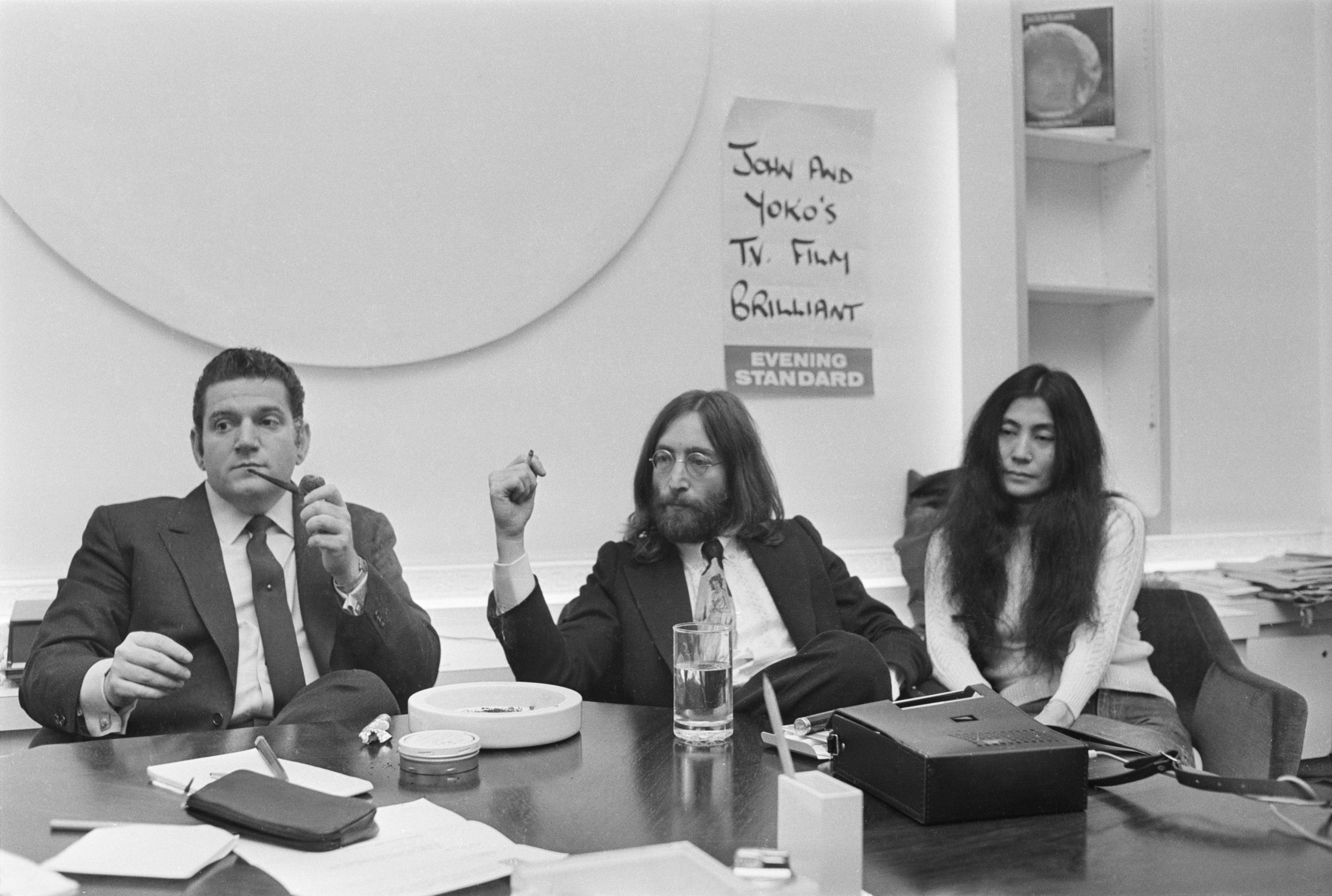

To do it, Klein took a divide-and-conquer approach. The Beatles’ finances were in terrible shape after the death of their longtime manager Brian Epstein in 1967 and the poor management of a company they started. Klein saw his opening. He invited John Lennon and Yoko Ono to dinner in his penthouse suite at a London hotel, serving “a carefully researched and prepared vegetarian meal—exactly the macrobiotic dishes John and Yoko preferred.” If Lennon had reservations, he was quickly won over by Klein’s pitch. He got the feeling that the manager “was cut from a different cloth than the others he’d met—the same plain, coarse, ordinary cloth that Lennon flew for a flag.” An understanding was reached, and Klein’s firm, ABKCO, was in business with the Beatles.

George Harrison and Ringo Starr warmed to Klein as well, impressed by his successes, but Paul McCartney was not on board—and Klein did little to win him over. One time, McCartney called for Klein while the manager was in a meeting with the Beatles’ company, Apple, and Klein told the receptionist to say he’d call back later. The receptionist came back to say McCartney was insistent: “Klein would talk to him now—or never. The Beatle clearly knew he was being snubbed in front of a roomful of his employees. Klein shrugged. ‘I can’t talk to him now.’

“Paul McCartney kept his word. He never spoke to Allen Klein again.”

Not long after that, the Beatles were no more, and the Rolling Stones, feeling snubbed by Klein giving so much of his attention to their rivals, took their business elsewhere. But Klein kept making money off the Stones in particular—though a series of negotiations, he ended up owning the rights to some of their music, and profited not only from compilation albums, but also from a later song that sampled from Stones music: The Verve’s “Bitter Sweet Symphony.” Klein drove a hard bargain with the song’s label, saying it could release the song as long as his company could purchase the rights to be its sole publisher. They agreed, and he paid them $1,000.

The song of course became a huge hit, and “ABKCO actively exploited the composition,” Goodman writes, “licensing it to be used in commercials around the world for various products, including Nike shoes and Opel automobiles. When the band decided the song was being overexposed and overused, they declined to license the original recording for any more commercials. As the publisher, ABKCO instead commissioned its own recording for commercial use.”

The move was typical Klein: a cunning gesture whose outcome he could see far clearer than his opposing party. That was how Klein ran his business, more or less, until his death at 77 in 2009.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com