The news sounds familiar: a virus with no treatment or cure is spreading abroad. But while Ebola dominated the infectious disease news over the last year, the latest infection making headlines is the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which has most recently hit South Korea, infecting 87 there and killing 6.

Could the two viruses cause similar damage?

Currently, MERS doesn’t appear to be able to spread like Ebola can. Though it’s in the same family of viruses as SARS and the common cold—both highly contagious—MERS appears to be less transmittable. While Ebola spreads through direct contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person, MERS doesn’t spread easily from person to person, and though it spreads through the respiratory tract, very close contact is needed, which is why the risk is higher for health care workers.

Both diseases have high fatality rates (around 3 to 4 of every 10 patients reported with MERS have died) and like Ebola, there is no vaccine or cure for MERS. But right now, MERS is more of a mystery to the medical community.

“Ebola has been around for 40 years so we have a pretty good sense of how it functions and its genome has been pretty stable,” says Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “MERS emerged in 2012 and we are still learning about it, and it may still be learning about us and evolving. It’s believed that when SARS spent more time circulating among humans, it evolved and became more transmissible.” Frieden says they haven’t yet seen that in MERS, but they’re watching: the CDC is currently sequencing the genome of the virus to understand how it might be changing, and to track its course.

The chance that MERS could change to become more transmittable worries experts. “Personally, I am more concerned about MERS following the course of SARS than I ever will be regarding Ebola becoming widespread outside of certain regions of Africa,” says Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior associate at the Center for Health Security at the University of Pittsburgh.

MORE What Is MERS? Here’s What You Need To Know

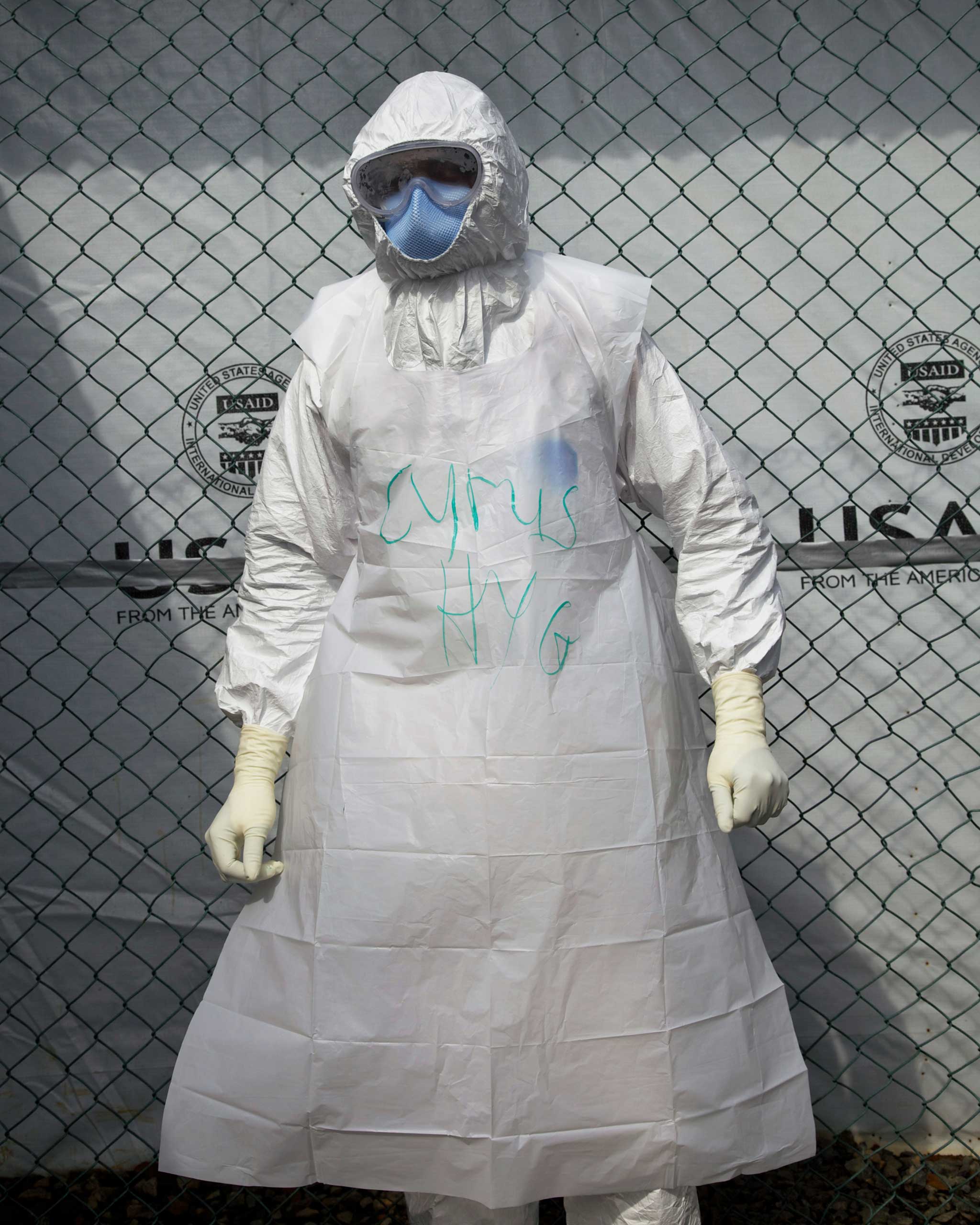

MERS has yet to take that course, Frieden says, but hospitals can be hotbeds for the infection. Through intensive investigations in affected countries, the CDC has determined that more than 90% of the cases could be traced health care exposures. So far there hasn’t been evidence of sustained community spreading. “Hospitals can become amplification points,” says Frieden. “It’s the case in measles, it’s the case for drug-resistant tuberculosis, it’s the case for MERS and SARS and Ebola. That’s where sick people go and that’s where vulnerable people are. It really emphasizes the importance of good infection control in the health care system.”

In May of 2014, the U.S. experienced two cases of MERS. In both instances, the patients were health care providers who lived and worked in the Middle East. Health departments around the U.S. have the ability to test for the virus, and the U.S. has already tested around 550 people in 45 states as a precaution since the disease first emerged in 2012.

MERS and Ebola share an important similarity: a lack of treatments or vaccinations. There’s currently no vaccine. “If there were a vaccine, it’s the kind of thing that might be useful in the camel population, but that’s very theoretical for the future,” Frieden says.

Only 20% of countries are currently able to rapidly detect, respond to or prevent global health threats from emerging infections, like MERS and Ebola, according to CDC data. Countries around the world and official health emergency responders like the World Health Organization have vowed to increase their ability to act during outbreaks that public health experts say are undeniably in our future. Frieden says the CDC in partnership with other countries is accelerating its Global Health Security program, which will increase preparedness worldwide. The CDC is making visits to eight countries in the next six weeks to move the program forward.

“Bottom line, both Ebola and MERS are emerging infections that show us why it’s so important for every country in the world to be prepared to find and stop health threats when and where they emerge,” Frieden says. “We do think the South Korea outbreak will well grow, but there’s no reason to think it can’t be controlled as other outbreaks have been controlled.”

Read next: 6 Dead, 87 Infected, 2,300 Quarantined: South Korea’s MERS Crisis

Listen to the most important stories of the day.

Photographing TIME's Person of the Year in Africa, Europe and the U.S.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com