The Sandtown neighborhood of Baltimore has all the markers of the depressed inner city. Unemployment is high, drug abuse is rampant and many houses are vacant and dilapidated. Less apparent—but equally insidious—is the prevalence of lead poisoning.

More than a decade before Freddie Gray suffered a fatal injury while in custody of the Baltimore Police Department, the Maryland native was allegedly the victim of the neurotoxin that contaminated the walls and windows in the dilapidated home where he grew up, according to a report in the Washington Post. Gray reportedly struggled academically, accumulated a criminal record and had trouble focusing—all outcomes associated with the long-term effects of lead poisoning.

Gray was not alone. Hundreds of thousands of young Americans were exposed to lead during their childhood, and, for many, the poisoning has been associated with dramatic problems in their day-to-day lives as adults. And despite the fact that lead was phased out as an additive in gasoline in the 1970s and 1980s, lead poisoning continues to affect children—most of them poor—to this day.

Baltimore, a city where nearly a quarter of the population lives in poverty, has become ground zero in the fight against lead poisoning. Many Baltimore homes were built in an era when the use of lead paint was common, and economic crisis has left many homes and neighborhoods in disrepair, exposing children to lead in chipping paint.

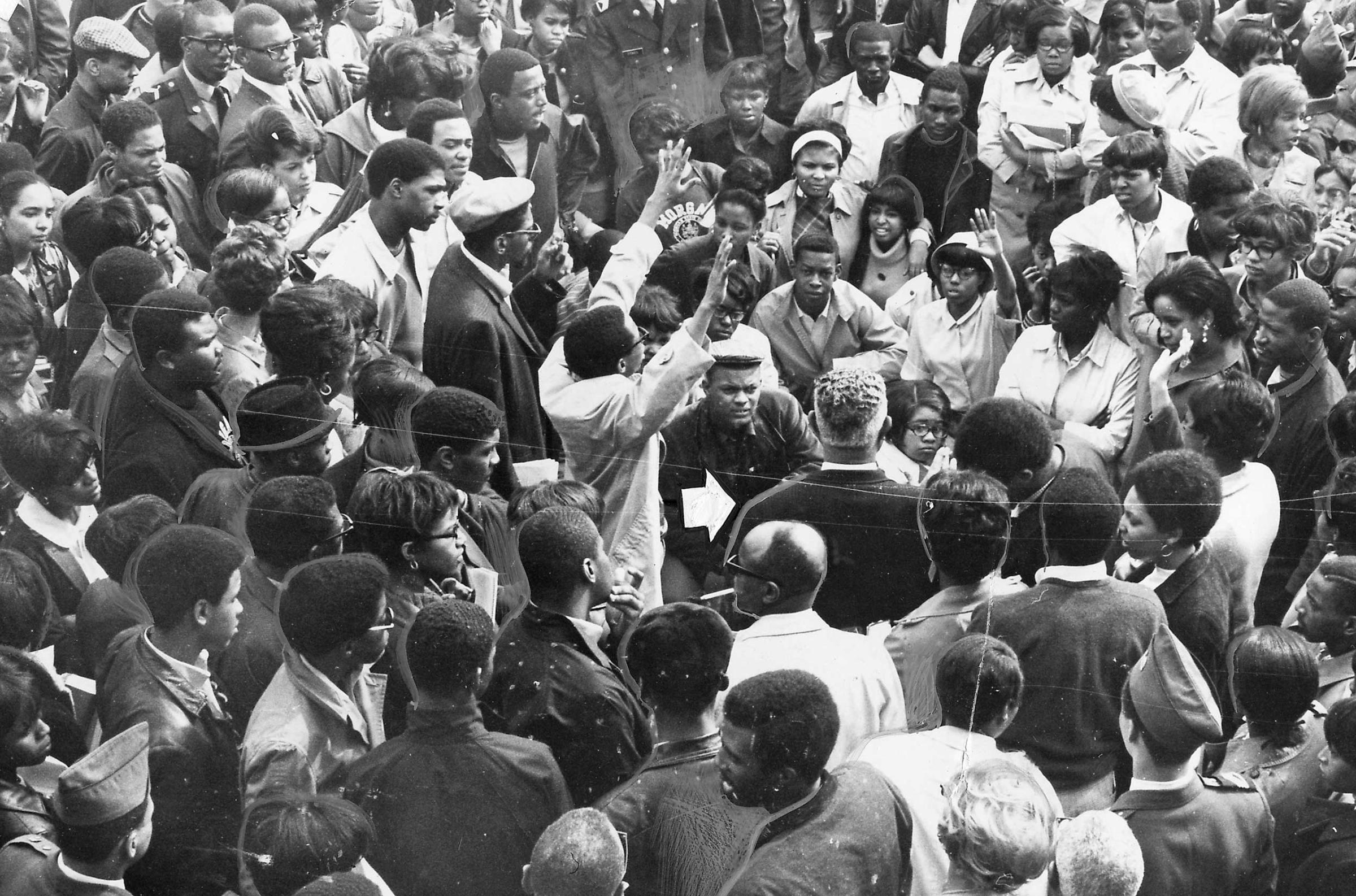

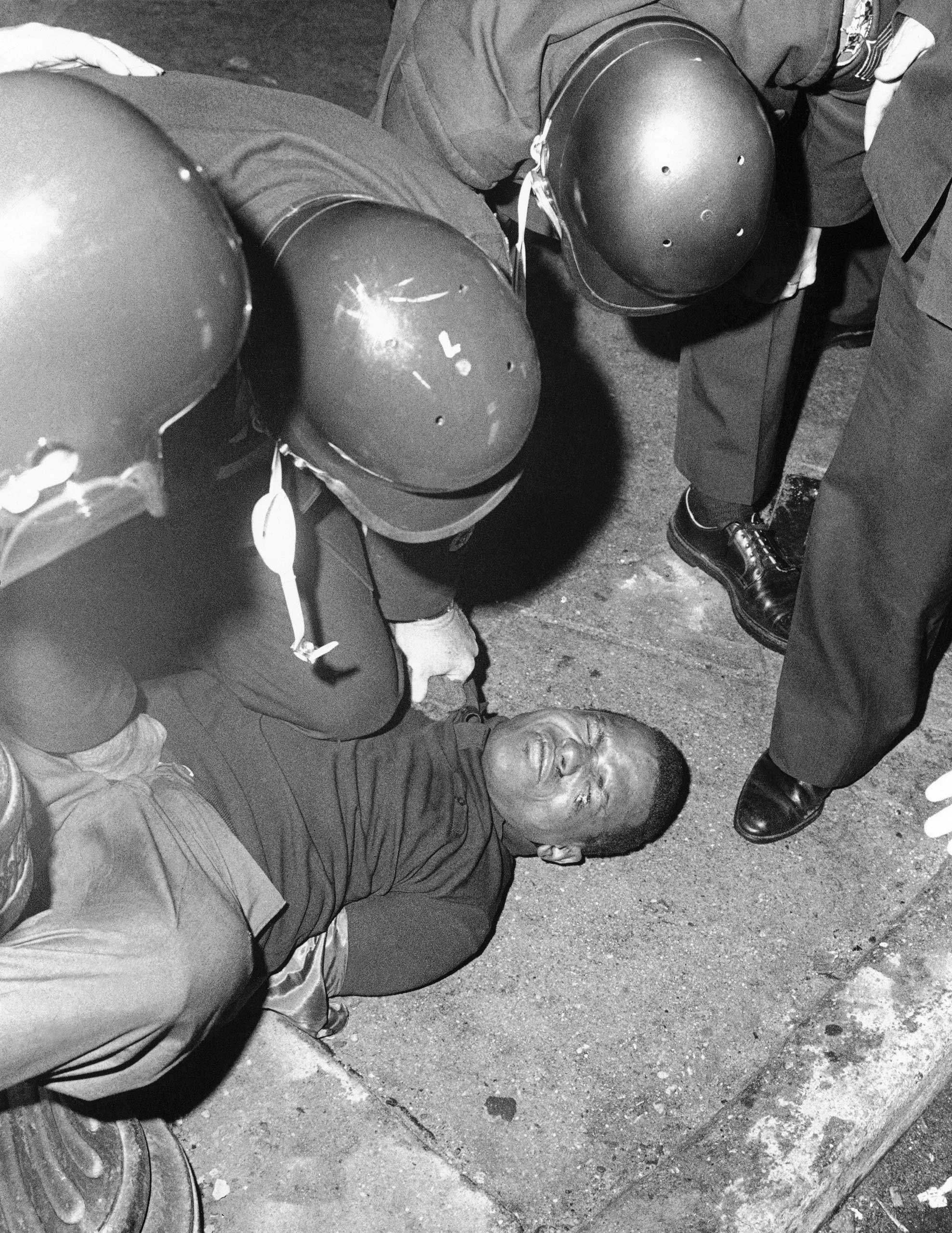

Baltimore Protests, Then and Now

Lead hasn’t been used in paint since 1978, and regulations require landlords to reduce the risk that their tenants are exposed to the substance. But many landlords opt to use risk reduction methods that contain lead temporarily, but leave tenants vulnerable in the longterm. For instance, a landlord may paint over lead paint with safe paint to meet regulations. That reduces the chance of exposure but doesn’t eliminate it. Furthermore, the regulations in Baltimore don’t address owner-occupied homes. To eliminate risk paint needs to be stripped entirely and windows and doors need to be removed, said Ruth Ann Norton, who heads the Baltimore-based Coalition to End Childhood Lead Poisoning.

“If land lords don’t comply with the law, we need to have strong and immediate enforcement,” she said. “But the truth is we have to couple that with investment to actually do the work, to hire young men and women to to replace windows and to remove the lead paint.”

Given that lead was banned in the 1970s, many people are unaware that the toxin is still present in some homes. More than 525,000 children were diagnosed with an elevated level of lead in the 200s, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Most people think lead is history, that we passed a ban, therefore it’s not a problem,” said Norton. “Since 1993, we have reduced childhood lead poisoning by 98%, but the job isn’t done.”

For those exposed to lead as children when their brains are still developing, the poisoning can be devastating. The cognitive effects of lead poisoning include diminished intelligence, shortened attention span and increased risk for developing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, according to Mount Sinai’s Dr. Philip Landrigan, who did pioneering research in the 1970s on the health effects of lead. “Unfortunately, it’s permanent,” he said. “The human brain displays very little capacity to repair itself once it’s damaged.”

And it might be difficult to recognize when a child has been exposed. Symptoms aren’t immediately visible, and a lead dust specimen the size of nickel could contaminate a 3,000 square-foot home, Norton said.

The effect of lead poisoning on the brain at an early age can hold back victims for life. Like Gray, many victims of lead poisoning have struggle to find and keep jobs. Some research has even suggested that lead poisoning causes sufferers to lose control of their impulses and behave erratically, which may make it more likely that they’ll commit violent crimes.

“If we’ve poisoned the child the rest of the investment fails, they can’t read, they can’t get to the classroom and they can’t learn,” said Norton “And I don’t want to fill our jails with kids.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com