Correction appended, April 21

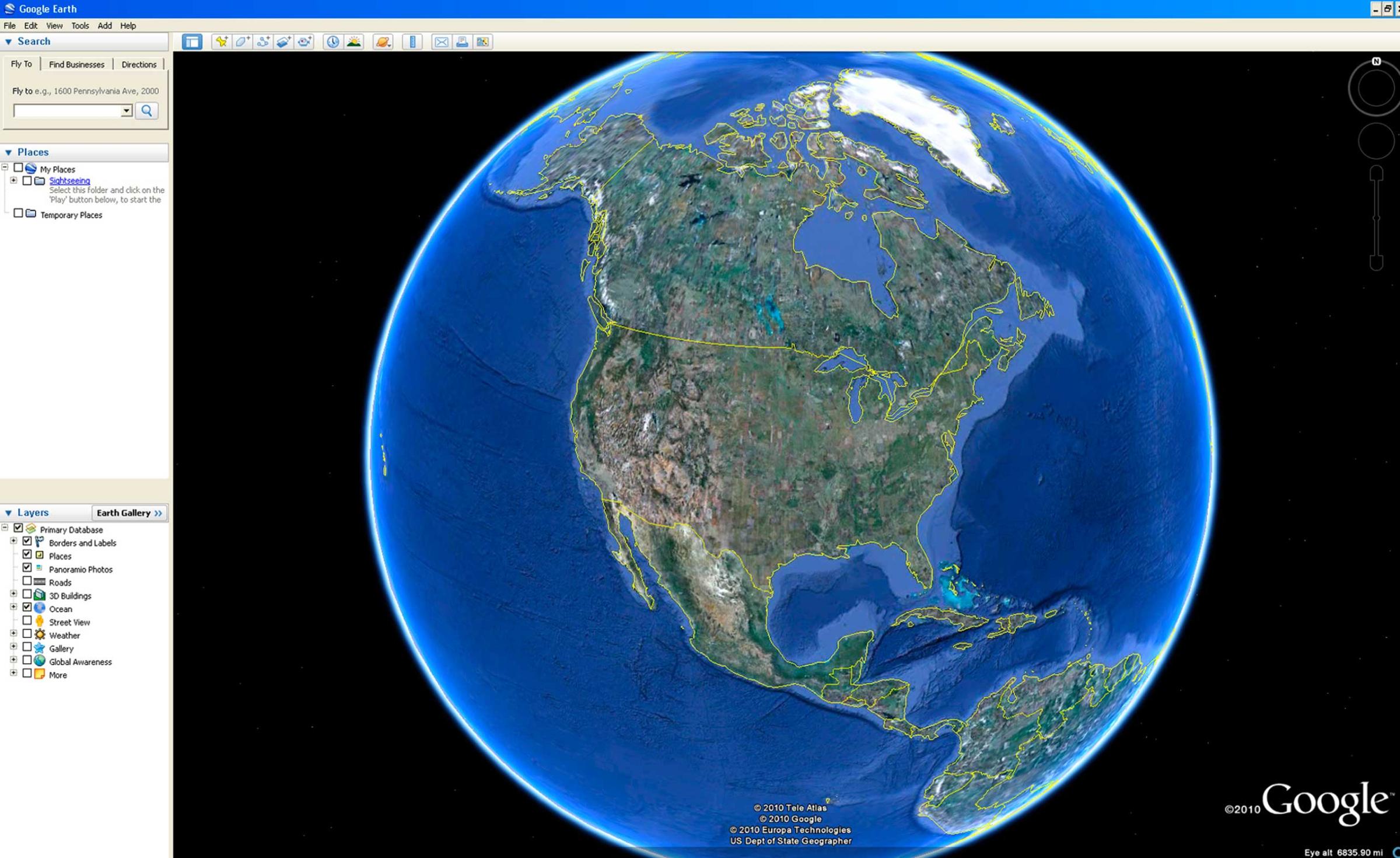

In late October John Hanke and several of his co-workers met for a reunion of sorts at Fiesta Del Mar, a Mexican restaurant near Google’s Mountain View headquarters. Hanke, a 10-year Google employee who led initial development of Maps, was once the founder of a small geodata startup called Keyhole that Google acquired in 2004. The fact that the one-time entrepreneur has stayed with the search giant for more than a decade makes him and his colleagues oddities in Silicon Valley. “There are quite a large number of [us] who are still at Google, and I have to say I don’t think anyone expected that when we first came in,” he says.

Google has used acquisitions to expand its workforce and launch new products since before it was a household name. Recently that strategy has become the modus operandi for technology firms in Silicon Valley. Facebook is using its fast-growing cash hoard to take control over sectors both adjacent to its core product (WhatsApp for $22 billion) and far-flung from social networking (Oculus VR for $2 billion). Microsoft, Yahoo and Amazon are doing the same, making big-ticket bets by buying Minecraft developer Mojang ($2.5 billion), Tumblr ($1.1 billion) and video game streaming site Twitch ($970 million), respectively. Even Apple, which long eschewed splashy acquisitions in favor of much smaller, less public buys, says it bought at least 30 companies during the last fiscal year, including the $3 billion purchase of Beats.

Overall spending on tech acquisitions topped $170 billion in 2014, up 54% from the previous year and more than double the amount spent in 2010, according to PrivCo, a research firm that tracks investments in private businesses. As the core of dominant technology companies get larger, they have come to depend on acquisitions not only to broaden their businesses but also to sustain the pace of innovation. “Companies are buying innovation,” explains Peter Levine, a general partner at venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. “As large companies need to be competitive and want to increase their footprints in a variety of different areas, one of the best ways to do that is through acquisition.”

The deals are a boon for startups as well. Venture capital is abundant, and companies can rely on investment rather than revenue to keep growing. If it’s not clear how a startup will eventually convert users into revenue, a buyout from a large firm can render that problem irrelevant—or at least less urgent. While investors and founders insist that launching a thriving self-supporting company is still the end-goal in Silicon Valley, “exiting” via a sale rather than an initial public offering can still net a lucrative payout. “It’s almost a goal for some of these companies as they start, to have that exit event,” says George Geis, a business professor at UCLA whose upcoming book, Semi-Organic Growth, analyzes Google’s acquisition strategy over the years.

But while snapping up a startup is now easy, holding onto its key employees is more difficult. Startup founders, who often think of themselves as entrepreneurs before engineers, are notoriously difficult to keep at large firms long. Partly, this is cultural: striking out on one’s own, idea in hand, is a fundamental part of the Silicon Valley ethos. The widespread availability of funding doesn’t hurt, either. That has left firms struggling to keep the expertise they may have spent millions acquiring. “When a firm is making a tech acquisition, they’re buying the talent as much as they’re buying the technology,” says Brian JM Quinn, a law professor specializing in mergers and acquisitions at Boston College.

A TIME analysis of startup founders’ LinkedIn profiles found that about two-thirds of the startup founders that accepted jobs at Google between 2006 and 2014 are still with the company. Amazon has retained about 55% of its founders over that time period, while Microsoft’s rate is below 45%. Facebook, with a 75% retention rate for founders, is beating its older competitors, but the company only began acquiring companies in significant numbers around 2010 or so. Yahoo and Apple, which have both gone on acquisition sprees under new CEOs Marissa Mayer and Tim Cook in the last two years, now have a similar retention rate to Google.

Google stands out among this cohort in large part because of the massive number of acquisitions it’s conducted. Overall at least 221 startup founders joined Google’s ranks between 2006 and 2014. Yahoo, the next closest competitor, added at least 110 founders to its employee roster in that time. Google’s internal calculation of its overall retention rate for startup founders through its history is similar to TIME’s, according to data provided by the company. Apple, Facebook, Yahoo and Microsoft declined to share any information on the retention of founders; Amazon did not respond to a request for data.

An examination of the ways Google tries to retain employees provides a window into the increasingly ferocious battle among the tech sector’s giants to expand through conquest. “Google,” says Geis, “has done a pretty good job—among the best in Silicon Valley.”

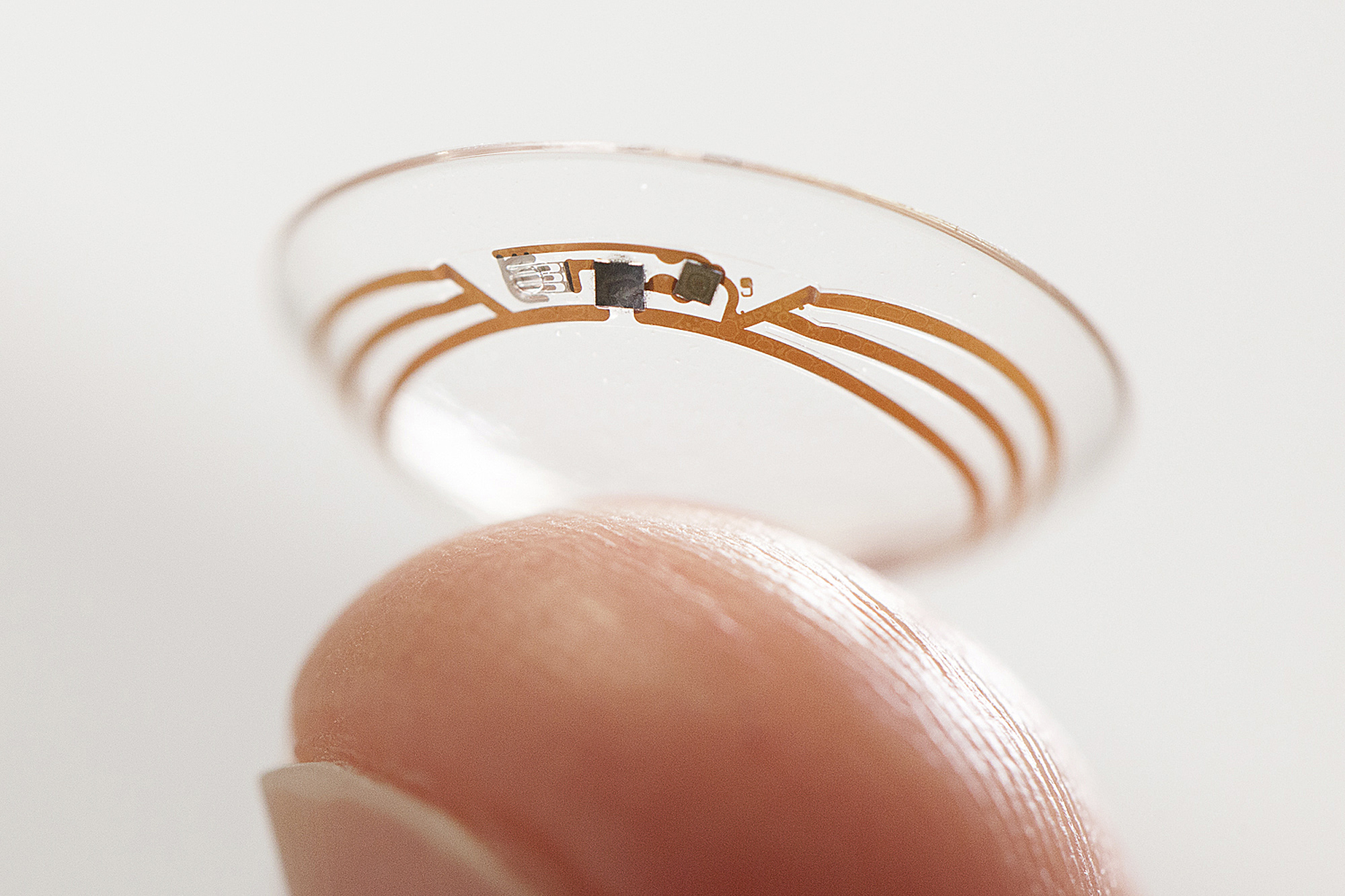

The 10 Most Ambitious Google Projects

‘The toothbrush test’

Even when Google was small, it wasn’t shy about spending. The company’s first startup acquisition, the 2003 purchase of Pyra Labs, forms the backbone of what is today Blogger, an online publishing platform. Since then, many of Google’s most well-known products, including Android, YouTube, Maps, Docs and Analytics, have originated from acquisitions. “M&A has obviously been a huge part of Google—and, I think, Google’s success—for a long time,” says Don Harrison, Google’s vice president for corporate development, who oversees the company’s acquisitions.

Before any deal is finalized, it has to pass what CEO Larry Page calls “the toothbrush test”: is the product something you use daily and would make your life better? “If anything matches the toothbrush test and relates to technology, then Larry has an interest in it,” explains Harrison.

Typically, Google buys occur in sectors where the company has already been experimenting itself. Harrison points to YouTube as a prime example. Google already had a video sharing service called Google Video in the mid-2000’s, but YouTube’s fast-growing user base convinced the firm to offer a then-eye-popping $1.65 billion for the startup, even though it was barely a year old and earned no revenue. Today, YouTube brings in billions of dollars of revenue per year and is the third most-visited website in the world, according to Web analytics firm Alexa.

But the return on investment on an acquisition isn’t only measured monetarily. It’s important to Google and other tech giants that the founders behind ideas worth paying for stick around as well. Harrison says founder retention is one of the significant factors Google measures as part of the “scorecarding” it does to evaluate its purchases. “We hold ourselves accountable to make sure that the founders are able to be successful within Google,” Harrison says. “It’s something that we’re not only working on at the time we buy the company but we work on for years after as well.”

Cash alone can’t convince the top startup founders to join Google. 2014 was the most active year for IPOs in the U.S. since the year 2000, according to IPO tracker Renaissance Capital, and Chinese online retailer Alibaba had the biggest public debut in world history, raising $25 billion in September. “As aggressive as we’re willing to be, we probably can’t match public company premiums right now,” Harrison admits.

So Google tries to find other ways to lure key talent.

‘A True CEO’

For Tony Fadell, the CEO of smart home company Nest, the decision of whether or not be acquired by Google was really a question of how he wanted to spend his time.

Google had begun courting Nest almost from the company’s inception, ever since Fadell showed Google founder Sergey Brin a prototype of the Nest Thermostat at a TED conference in 2011. At the time, Fadell wasn’t interested in a buyout. “I wanted to keep it as a startup as long as possible,” he says.

But as Nest grew, so did Fadell’s logistical headaches. By 2013, he says he was spending 90% of his time on what he calls “back-of-house stuff”: managing finances, talking to investors, wrestling with taxes and fending off patent lawsuits. “There was a lot of selling to multiple entities that we were doing the right thing,” he says.

When Google came knocking again, offering a big payday and the chance to keep Nest’s name brand intact—a key requirement for Fadell—an acquisition seemed more appealing. Now Fadell says he spends 95% of his time focused on product development and key relationships. Nest, meanwhile, has gotten access to resources that would have taken much longer to accrue independently. The company launched in five new countries in 2014, but Fadell thinks they would have only reached two without Google’s help.

In many ways, the Nest acquisition is the ideal scenario startup founders envision when they agree to be swallowed by a larger company. Harrison, Google’s M&A head, calls Fadell a “true CEO” and says Google execs serve more as a board of directors for Nest instead of supervisors. Fadell says he hasn’t had to get formal approval for anything from Google, though he reports directly to Larry Page and meets with the Google CEO a few times per month. “He’s like, ‘Call me when you need me, but this is for you to run,’” Fadell says of his relationship with Page. “He gives us the freedom, so I run with that. Only when it’s really major decisions do I really touch base with him.”

Some founders who don’t quite have Fadell’s free rein are still granted a certain level of autonomy. Skybox Imaging, a satellite manufacturer that Google acquired for $500 million last summer, reports to the company’s vice president of engineering for geo products but maintains separate offices from Google in Mountain View. “We kind of get a little bit of the best of both worlds,” says Ching-Yu Hu, one of the four Skybox founders that now works at Google. “We’re all Googlers now so we have access to all the infrastructure there, but at the same time we’re semi-autonomous.”

The company has experimented with more direct incentives to maintain an entrepreneurial spirit. For a few years in the mid-2000’s Google handed out Founders Awards valued at as much as $12 million in stock to teams that developed successful new products like Gmail and Google Maps. Today awards are a little less explicit, in the form of more traditional of raises or promotions. Google works closely with founders in their first 90 days on the job to insure they’re getting acclimated well, but check-ins on founders’ progress can continue for years, depending on the acquisition.

At the core of Google’s pitch to founders is the opportunity for bountiful resources. Sure, those can be scratched and clawed for independently, but going it alone requires a lot more time, money and luck than hitching your wagon to one of the richest companies on Earth. “It was a pretty compelling pitch,” Hanke recalls of his own deliberations about whether to sell Keyhole to Google. “We could achieve a lot more standing on the shoulders of all that was going on at Google versus trying to do it on our own as startup.”

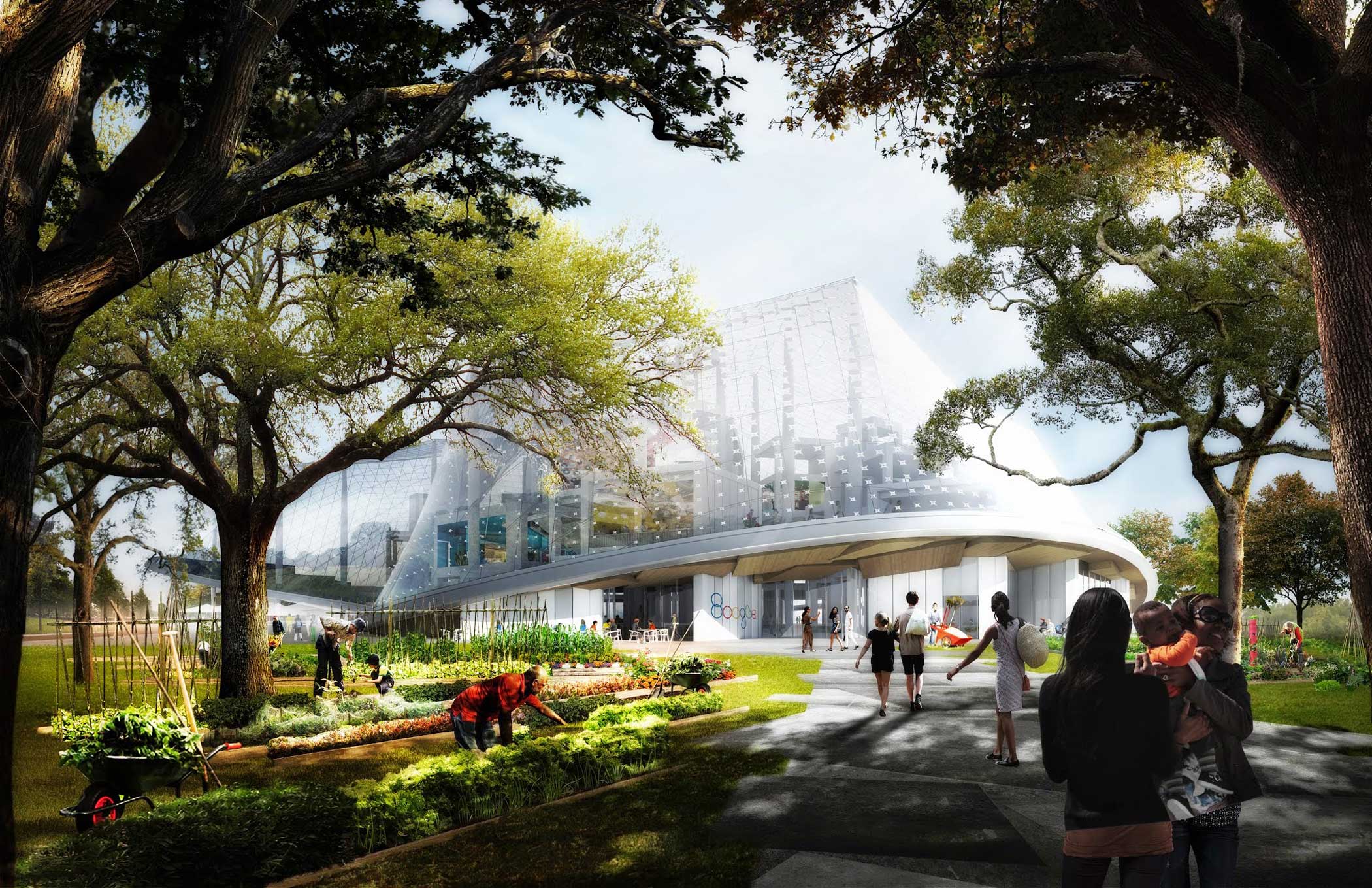

Google's New Headquarters Looks Like a Giant Glass Forest

When Founders Leave

Still, even Harrison admits that not every acquisition goes smoothly. Because California is an at-will employment state, workers can generally be fired or choose to leave at any time. Tech companies try to ensure founders stick around for a while by offering a stay bonus or using “golden handcuffs,” which often meter out the payday for a big acquisition in company shares that vest over several years. Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp, for instance, includes $3 billion in restricted stock for WhatsApp employees, but they can’t fully tap into those funds unless they stay at the company for four years.

In some cases, golden handcuffs aren’t enough to keep founders on board. Kosta Eleftheriou joined Google in October 2010 through the acquisition of his keyboard app BlindType, but life at the massive company wasn’t what he envisioned. Eleftheriou says he was relegated to maintaining Google’s stock Android keyboard rather than envisioning ways to improve the product. He left after one month, leaving half of his compensation package for the acquisition on the table (he says the total acquisition price was in the seven figures). Now he’s a founder again, with a new keyboard app called Fleksy that has been downloaded 4 million times.

“It was a mismatch between what I was expecting and what happened,” Eleftheriou says. “I think that was partly due to maybe some unrealistic expectations on my side on how much creative freedom I would have. I was hoping to be part of a bigger picture than just some engineer working on something by themselves.”

As the founder of a small company that didn’t make huge headlines when it was acquired, Eleftheriou’s experience isn’t uncommon in the Valley. “Unless they’re sufficiently large, very few acquisitions continue to run independently,” says Justin Kan, a partner at the venture capital firm Y Combinator and cofounder of Twitch. “Oftentimes founders are rolled up inside another group inside of the company. They can’t make decisions as freely as when they were entrepreneurs. That affects people’s willingness to stick around.”

Sometimes founders simply crave the excitement of starting something new. Uri Levine was the only one of Waze’s three founders who chose not to join Google when the traffic app was acquired for $1 billion in June 2013. Instead he launched a new startup—his sixth—called FeeX, which aims to help people reduce investment fees in their retirement accounts. “Entrepreneurs, they are driven by a passion for change,” Levine says. “As soon as you become part of a large organization, you cannot change anymore.”

Google’s also had some more high-profile misfires. When it made its largest acquisition ever, the $12.5 billion purchase of handset maker Motorola Mobility, Page hailed it as an opportunity to “supercharge the Android ecosystem.” But Motorola’s phones failed to gain traction, the subsidiary racked up $1.4 billion in losses for Google, and the company offloaded the handset division to Lenovo for $2.9 billion in 2014. Harrison defends the deal as a smart acquisition because of the patent portfolio that Google acquired, helping the company defend itself from lawsuits by Apple and Microsoft (Geis, who has studied the transaction closely, called it “a wash” for Google).

The Spree Continues

At Google, at least, there are opportunities for change for some founders who join the company. Hanke, the former Keyhole CEO, spent several years heading up Google’s geo services, but now he’s in charge of Niantic Labs, a separately branded unit that Google bills as an “internal startup.” Hanke’s team develops apps that increase the opportunity for digital interaction in real-world environments, like InGress, a mobile game that requires players to visit physical locations to gain power ups. Android founder Andy Rubin also took on a role far removed from smartphones when he became the head of Google’s robotics division in 2013. (Rubin eventually left Google in October after nine years at the company).

Google is constantly making these kinds of bets on the future, and it needs new blood with fresh ideas to sustain them. The company is currently wrestling with multiple threats to its core business, search, including a declining share of desktop searches and a mobile market where Amazon is stealing product search queries and Facebook is taking ad dollars. If Google is to maintain its steady growth, it will eventually have to tap into a new revenue source somewhere, and that may well stem from an acquisition. The company may view Nest as the key purchase that ensures its future dominance, given Fadell’s perch. “Founders and everyone else at these startups, they want to be businesspeople,” he explains.

And the big businesses themselves? They want to ensure they don’t miss out on the next big thing. “The ability to move quickly in rapidly changing markets is one of the major drivers,” says Geis of the acquisition spree. “If you want to effectively compete and innovate continually, it can’t all be from within.”

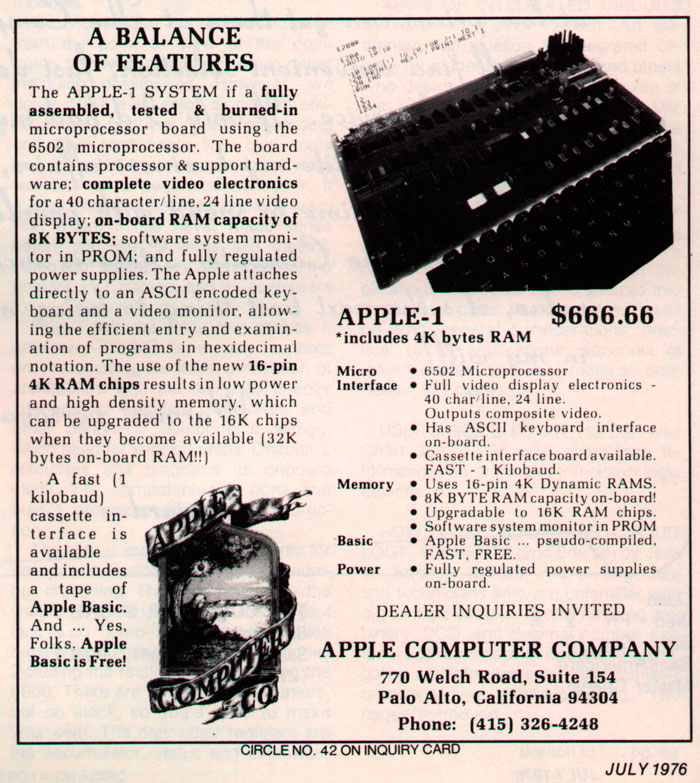

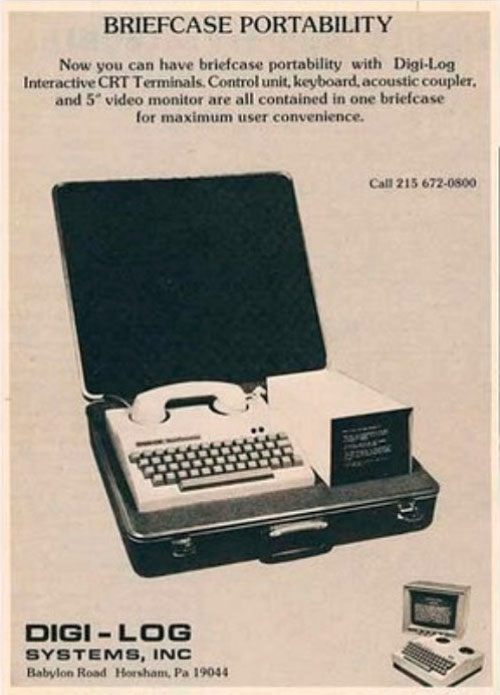

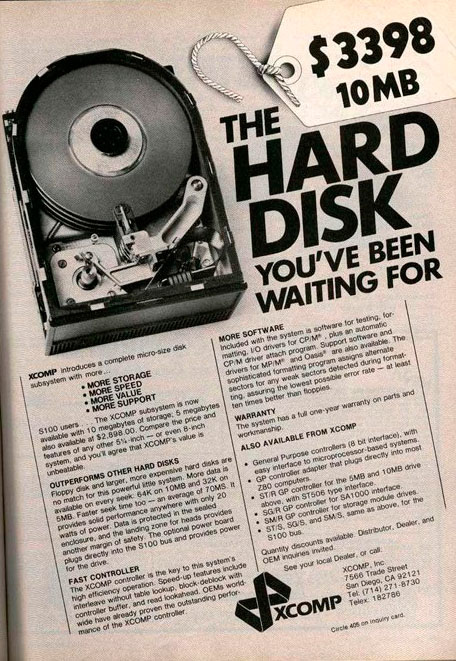

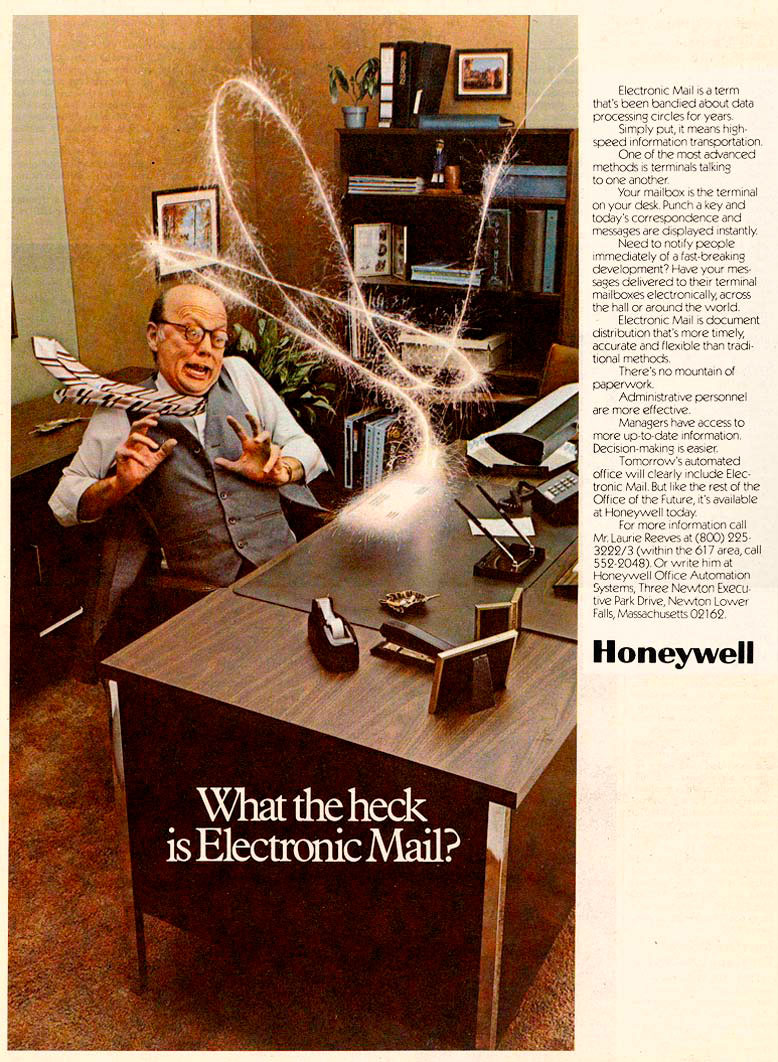

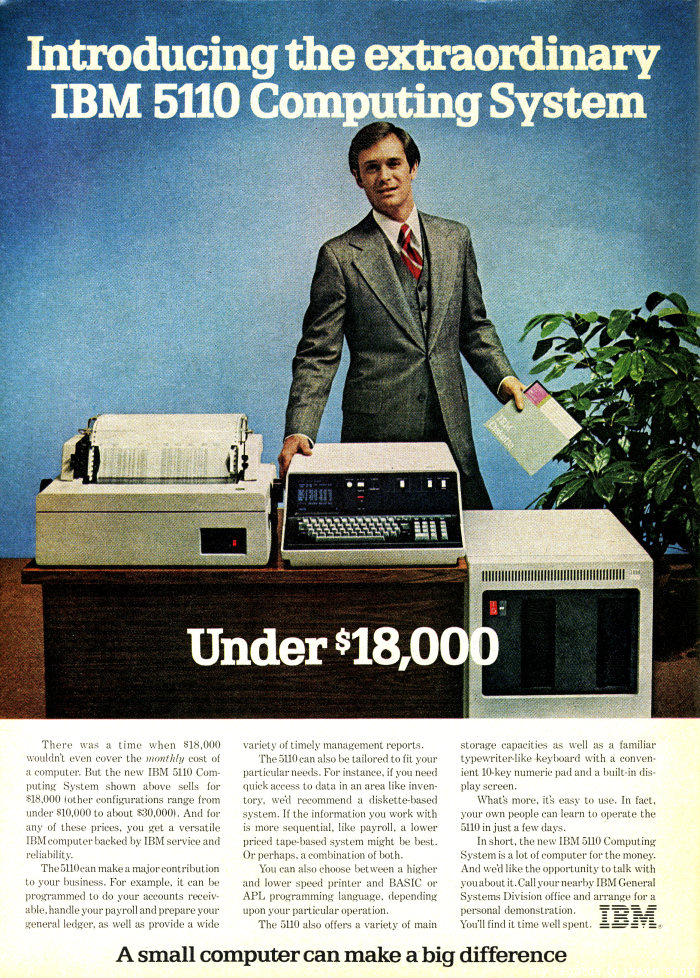

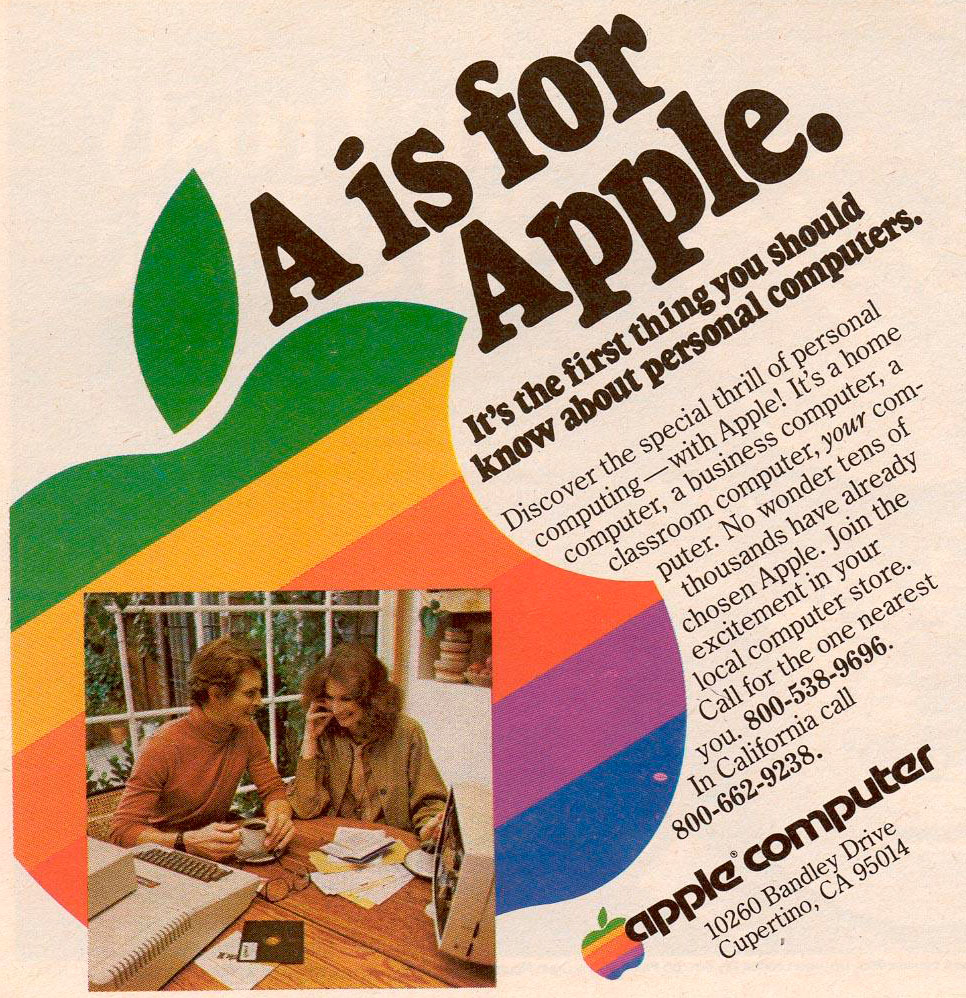

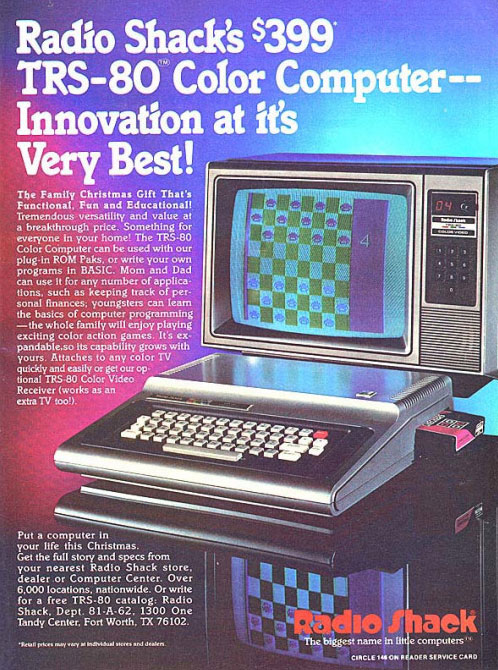

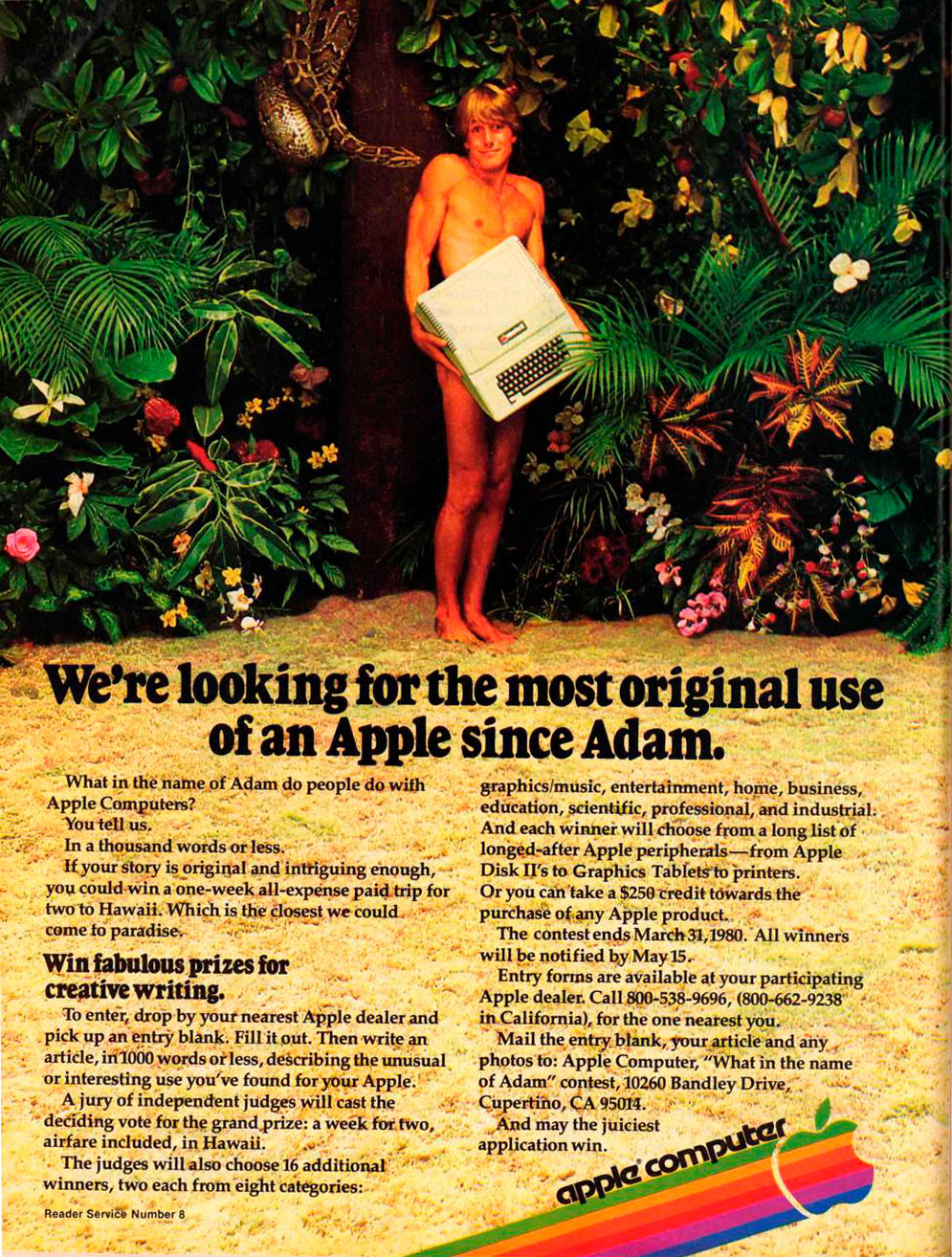

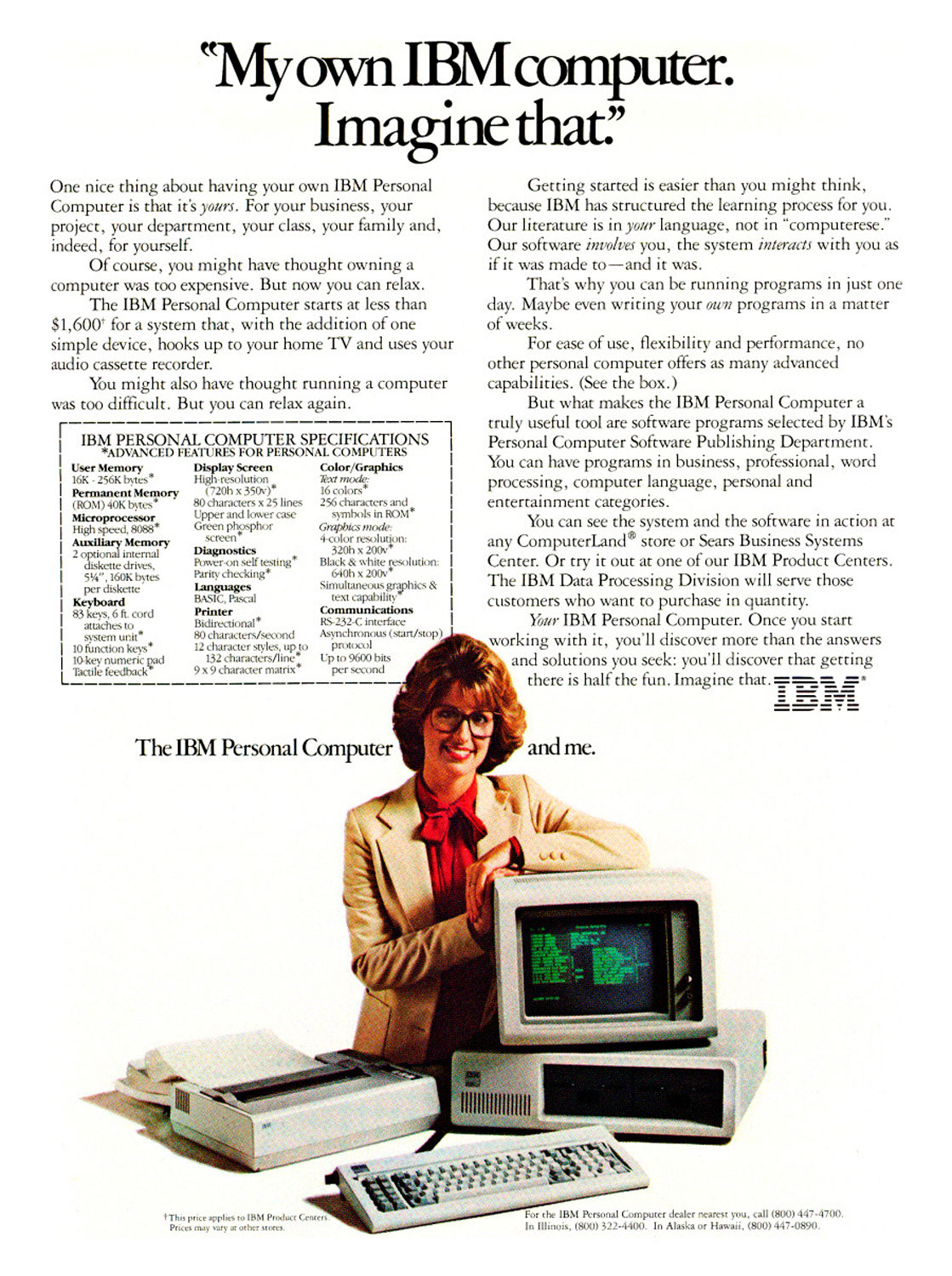

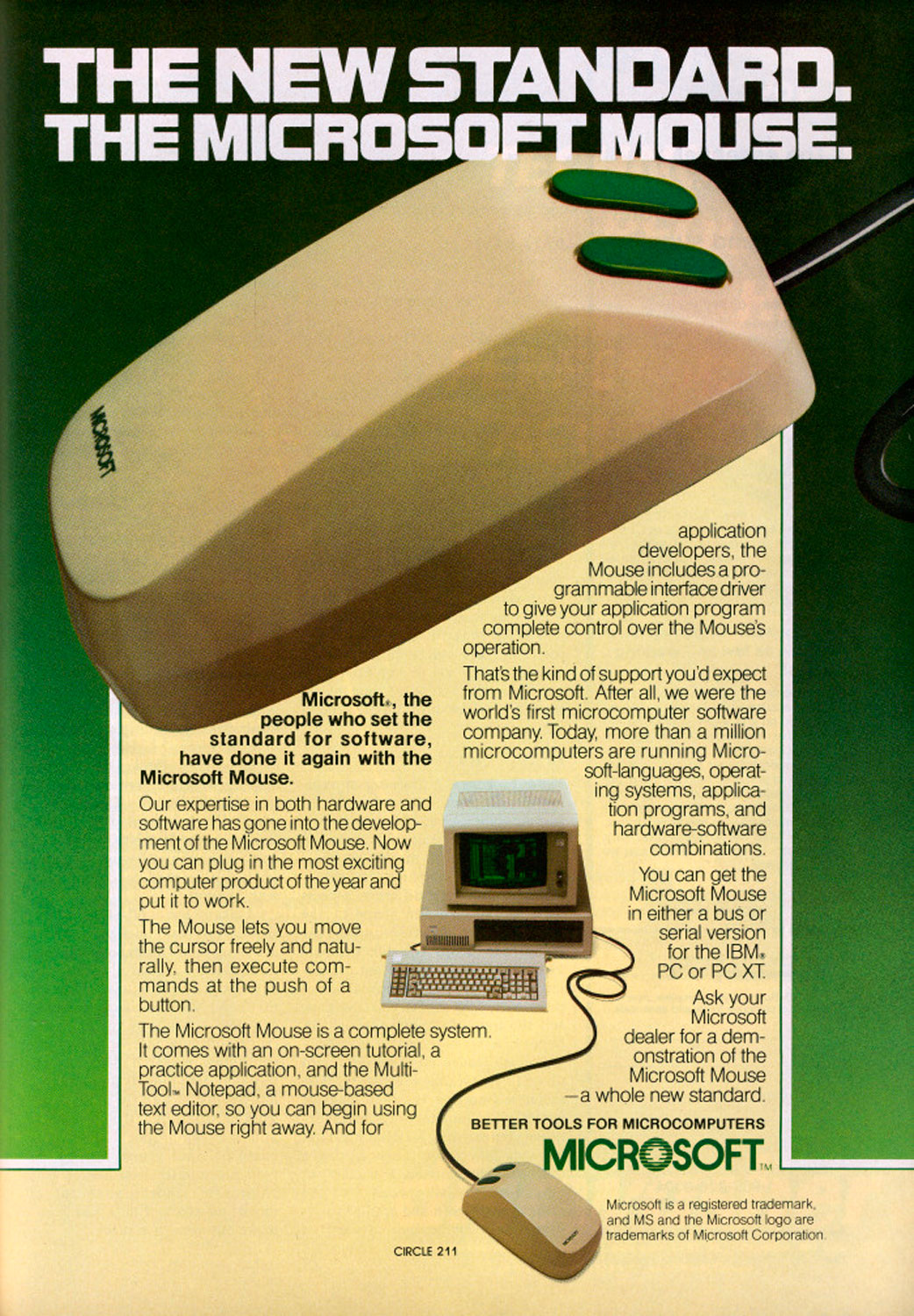

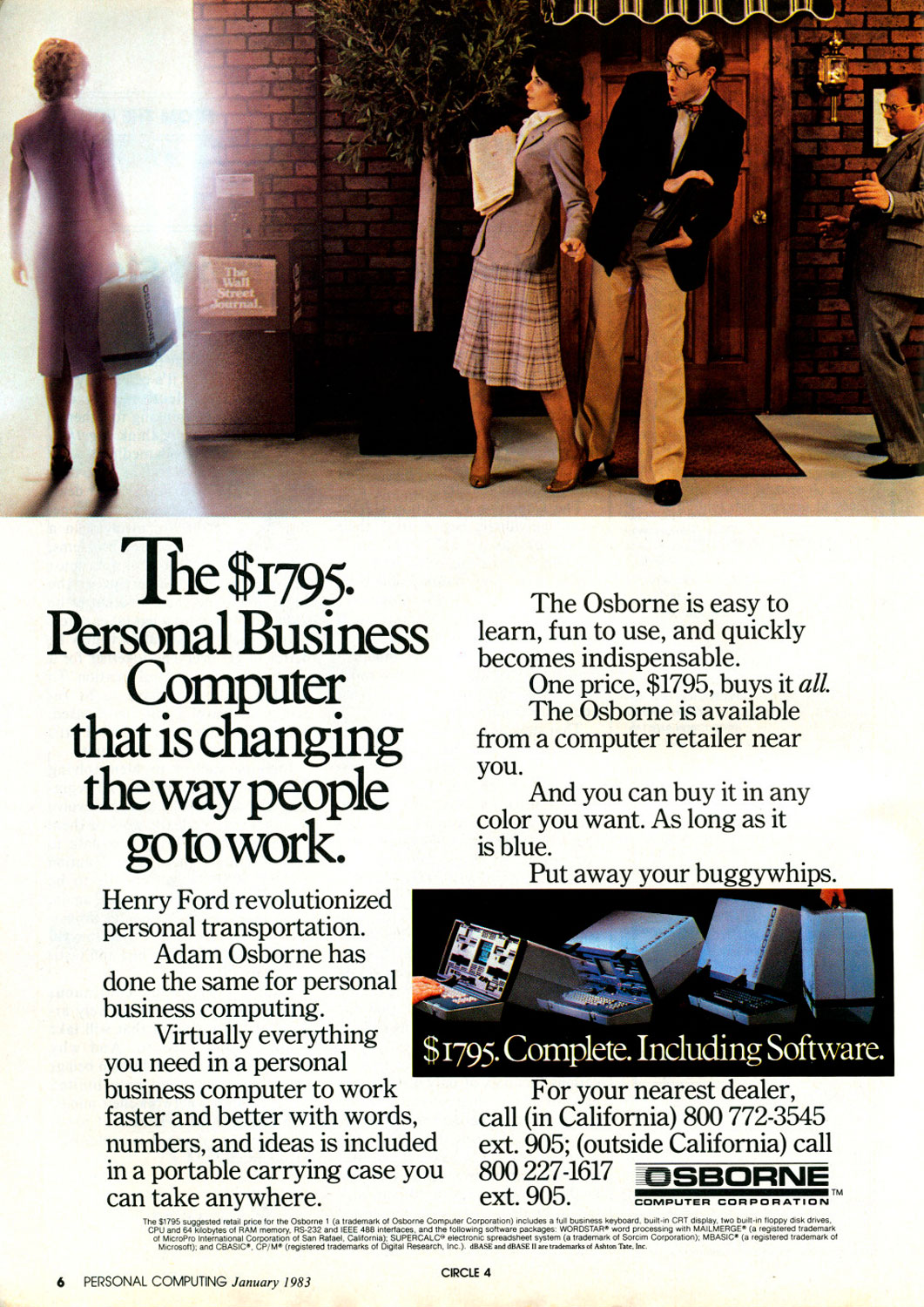

These Vintage Computer Ads Show We've Come a Long, Long Way

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly described George Geis. He is a business professor at UCLA.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com