Welcome to this week’s edition of TIME’s LightBox Follow Friday, a series where we feature the work of photographers who are using Instagram in new and engaging ways. Each week we will introduce you to the person behind the feed through his or her pictures and share an interview with the photographer.

This week on #LightBoxFF, TIME speaks with Moscow-based photographer Brendan Hoffman (@hoffmanbrendan) — co-founder of the photography collective, Prime — about using Instagram to document the recent unrest in Eastern Ukraine and the civilian life that endures amid the violence.

Lightbox: What is the purpose of your feed? What does Instagram provide for you that other platforms don’t?

BH: Instagram manages to do a few different things for me, and I use it in a few different ways. Primarily, it’s a way for me to share what I’m seeing when I’m on assignment. I like showing people what I think is important. Beyond that, I still sometimes post pictures from my daily life or of my friends. Though it’s a professional tool, I don’t feel that my feed has to be totally professional all of the time. I think including glimpses of my own life gives more authenticity and trustworthiness to the news photos I post, which reach an audience that might not always follow or trust the mainstream media.

Mar.22, 2014. Happy Thanksgivukkah from a rather lonely hotel room in Yekaterinburg, Russia. This phase of my project for Pulitzer Center has been tryingly difficult, capped off by the fact that I’m shooting video, which I wouldn’t exactly call a passion. Still, I believe more strongly every day that my topic/subject here is worthwhile, and that the need for patience and persistence is not to be feared.

Lightbox: How are you using Instagram now, and how has it become a part of your professional practice?

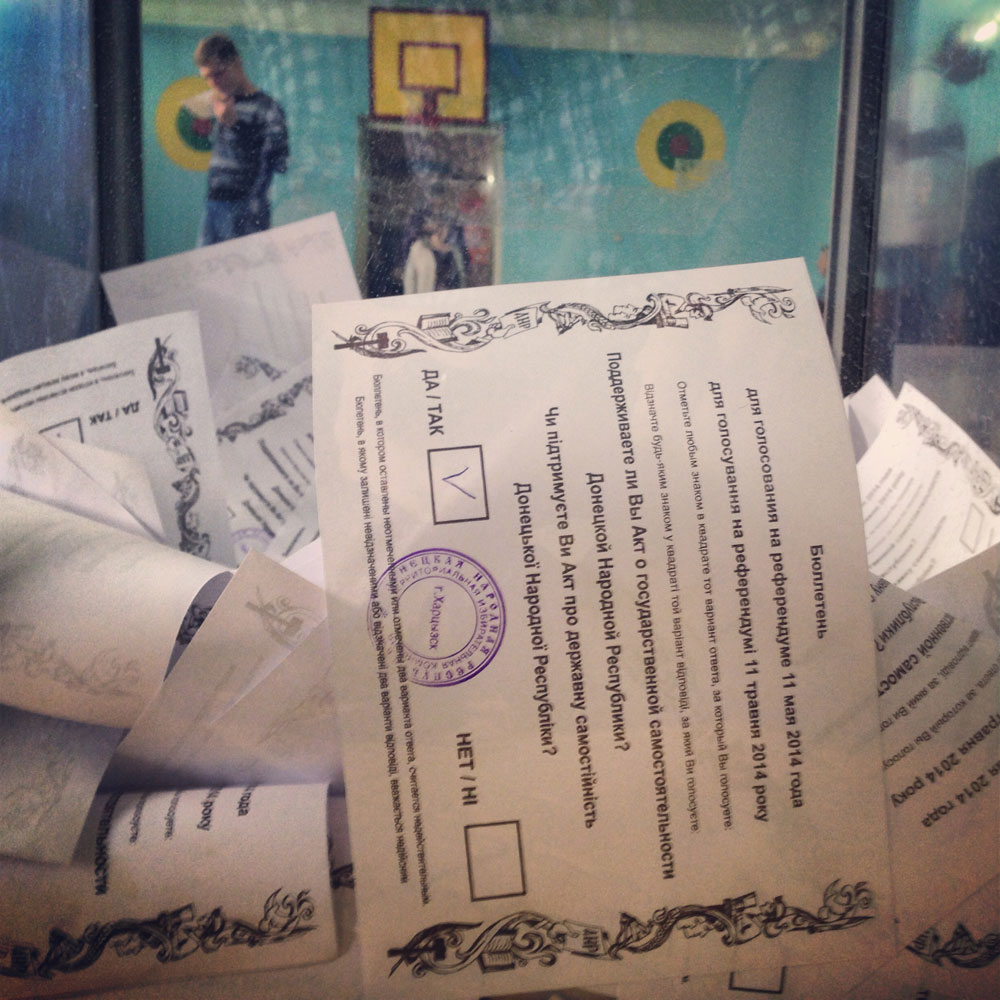

BH: I don’t carry a big dSLR camera with me in my daily life. My phone is my walking-around camera. Ninety-nine percent of the time I post photos taken with my phone, which lets me work more instinctively and avoid over-thinking my pictures. There are exceptions, however. The photo in this gallery of the funeral procession was taken with my professional camera. I did it this way for two reasons. First, I didn’t have a good photo from my phone to post but I wanted to share the story of a civilian killed in tragic circumstances. Second, in the context of a funeral, when people are allowing you to photograph a very personal and difficult situation you owe it to the family to make strong pictures, with a purpose. Something about pulling out a phone to photograph a corpse strikes me as undermining the promise of professionalism that allowed access in the first place. The crisis in Ukraine is a story I’ve been following since early December of last year. I covered the Maidan protests in Kiev, and while the nature of the conflict is very different now, it’s no less consequential. I’ve been in Eastern Ukraine for about five weeks, primarily on assignment for Getty as well as the Washington Post. I moved to Moscow just last summer to pursue my long-standing interest in the region, so this is a story I can’t ignore.

Lightbox: Which post inspired the most audience feedback and engagement, and why do you think that photo got people’s attention?

BH: The most likes one of my pictures had — 807, at last count — was of my friend Scott’s dog napping under a window. Other highlights are a mountain landscape in the Caucasus and two ducks swimming on a Moscow pond in the fog. In general, it seems serene and beautiful photos win out. Of course, likes are an imperfect metric for measuring engagement, since people are a bit hesitant to hit the like button on a tragic picture. Being in Eastern Ukraine for the past five weeks, I’ve photographed a lot of horrible and violent scenes, which is a bit new for me. And inevitably, it’s forcing me to grapple with the old dilemma of aestheticizing violence and death. I guess the lesson here is that beauty is a powerful tool for promoting audience interaction.

Apr. 17, 2014. This is a real place. We drove along a meandering dirt track through a few valleys to the tiny village of #Juta, then set off on foot following a cow path. Our reward: Chaukhi Mountain, all to ourselves.

Lightbox: Do you envision Instagram ever losing its appeal, and if so, how would you replace it?

BH: Inevitably Instagram will give way to something else; it’s not a perfect platform. For example, I don’t feel like the work I post on Instagram leads people to visit my website or engage in other ways outside the app — but then again, I’m not explicitly asking for that, either. Presumably, if and when Instagram is overtaken, it will be because something better has come along, though the key to Instagram’s success seems to be that it doesn’t try to be everything at once. Or, maybe it will remain a niche for professional photographers while [everyone else] moves on to something else. But whatever else comes along is only going to succeed if it further develops the connection between the photographer and his or her audience.

Brendan Hoffman is a news and documentary photographer based in Moscow and co-founder of the photography collective Prime. Follow him on Twitter @brendanhoffman.

Mia Tramz is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME.com. Follow her on Twitter @miatramz.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com