If one were to ask the foremost contemporary black photographers to name their biggest influence, it is likely that they would answer with the same name: “VanDerZee.” In Through A Lens Darkly, a new documentary by filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris that traces the history of African American photography, artists Hank Willis Thomas, Lorna Simpson, Anthony Barboza and others discuss James VanDerZee’s impact on both black photography and, perhaps more importantly, identity. Known mainly for his exquisite studio portraits and unique retouching techniques, VanDerZee (1886 – 1983) not only documented, but articulated, life in Harlem during and beyond the famed Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

Before cameras and film became widely accessible to the average American, studios like VanDerZee’s provided the very few photographs that would be made of a person in their lifetime — and in some cases, after their death. It seemed that VanDerZee intuited early on in his photographic career that his portraits of African American men, women, husbands and wives, brides and grooms, social clubs and political figures were not just for the client who commissioned them, but for history. He took great care in positioning his subjects, in lighting them, in setting up the environments in which they were placed and in choosing which objects were placed around them. The retouching he applied to each portait served to make his subjects and their surroundings as beautiful as possible. Every aspect of the photograph was considered as he crafted a record of what would become the seed of America’s black middle class.

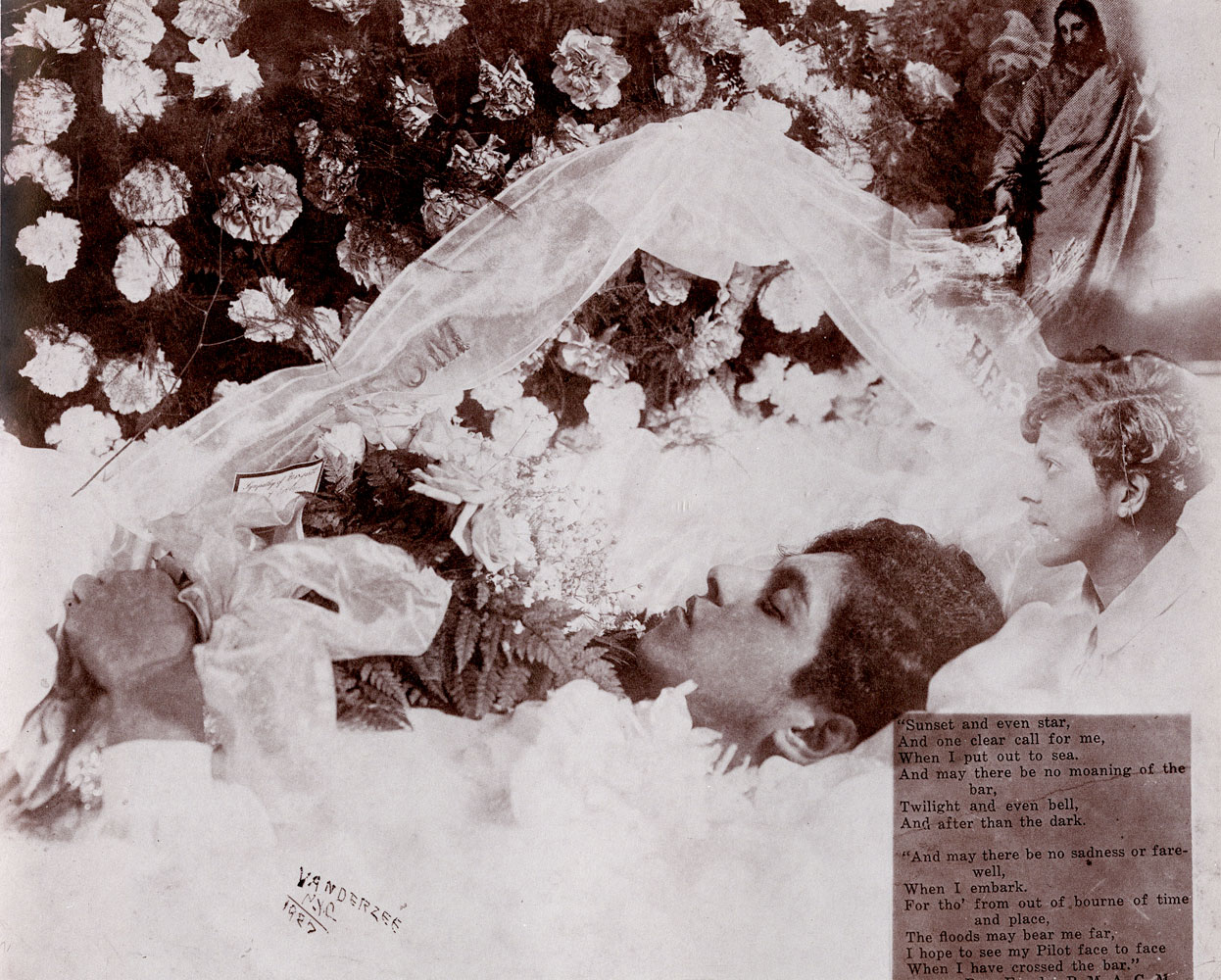

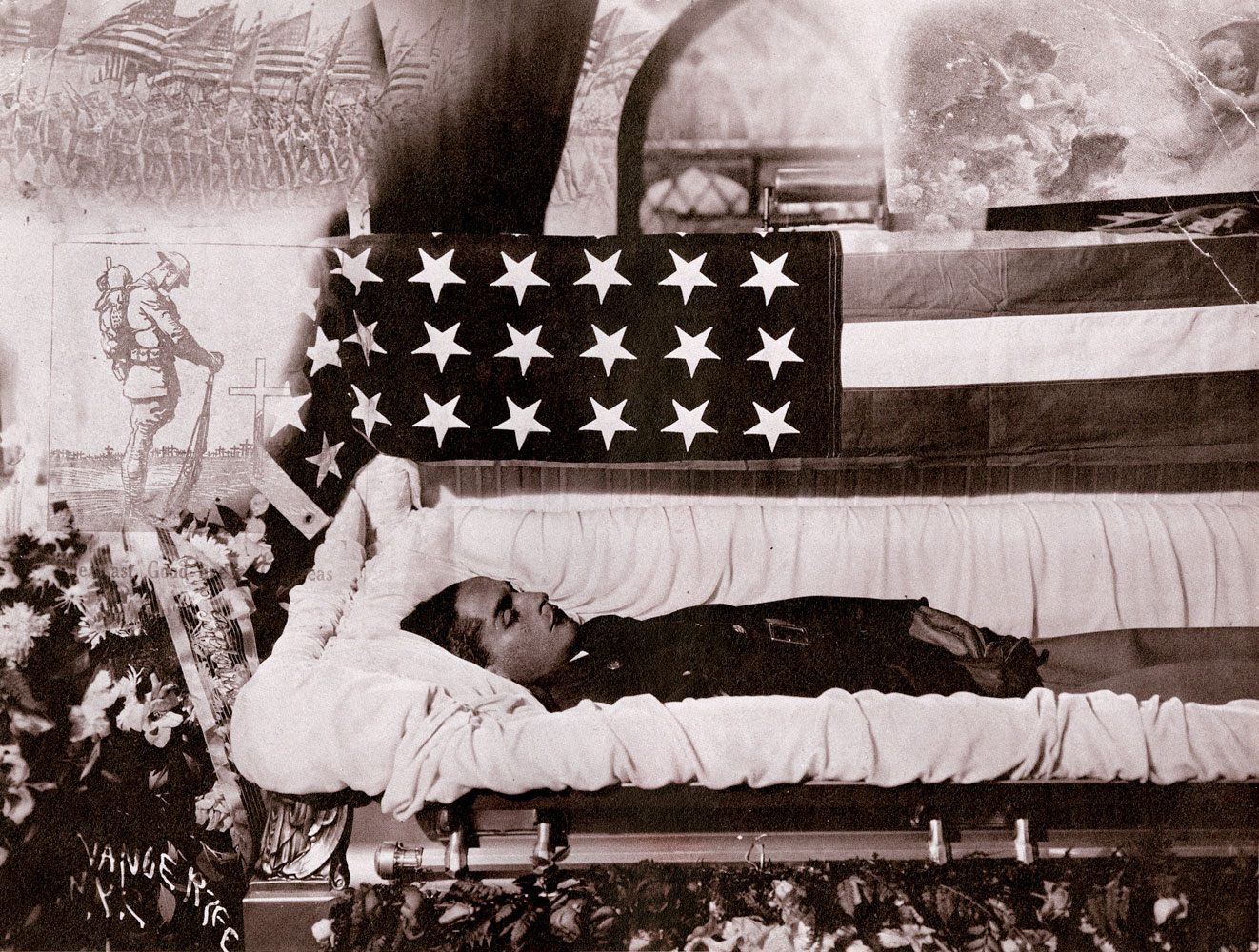

Another service VanDerZee provided through his studio was funerary portraits. For those with the financial means, post-mortem photographs were not uncommon at that time. In some cases, especially when it came to very young children, a funerary portrait would be the only photograph ever taken of a person, and the only photograph their families would have to remember them by. For people who had migrated to Harlem, funerary portraits could be sent back to relatives they had left behind who could not attend a loved one’s funeral. VanDerZee applied a darkroom technique he used in some of his studio portraits to his funerary photographs, using photo montage to insert poems and spiritual imagery around the subject. In certain instances, VanDerZee photographed the deceased both in life and in death, and would montage their original portrait over the funerary one. This was the case with his daughter, Rachel, who died at 15 (slide 2).

Later on in his life, in 1978, these funerary portaits were assembled into a book, The Harlem Book of the Dead, and were accompanied by original poems and text by poet Owen Dodson and artist Camille Billops, as well as an intimate interview with the then-91 year old VanDerZee. The book is an ode not only to lives past, but to a time past — and to a slice of history that might otherwise be lost. It is a meditation on death and loss, but also on beauty. In the book, and in his work, VanDerZee was not only a photographer, but a custodian of memory.

Mia Tramz is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME.com. Follow her on Twitter @miatramz.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com