Based on national pay-disparity numbers, a hypothetical American woman would have to keep working until roughly April 14, 2015, in order to make the same amount of money as a man doing the same work would have made in 2014 — which is why the activist group the National Committee on Pay Equity has selected Tuesday as this year’s Equal Pay Day. Though the topic will get extra airtime today, the debate about equal pay is nothing new.

In February, 1869, a letter to the editor of the New York Times questioned why female government employees were not paid the same as male ones. “Very few persons deny the justice of the principle that equal work should command equal pay without regard to the sex of the laborer,” the author wrote. “But it is one thing to acknowledge the right of a principle and quite another to practice it.” The author noted that the U.S. Government employed 500 women in the Treasury department, but that they made only half as much as their male colleagues:

“Many of these women are now performing the same grade of work at $900 per annum for which men receive $1800. Most of them, too, have families to support; being nearly all either widow or orphans made by the war.”

That year, a resolution to ensure equal pay to government employees passed the House of Representatives by almost 100 votes, but was ultimately watered down by the time it passed the Senate in 1870.

In 1883, communications across the country ground to a halt when the majority of the workers for Western Union Telegraph Company went on strike, partly to ensure “equal pay for equal work” for its male and female employees (among other demands). The strike wasn’t ultimately successful, but it was a very early public demand for fair pay for women.

By 1911, significant progress had been made. New York teachers were finally granted pay equal to that of their male counterparts, after a long and contentious battle with the Board of Education.

In the 20th century, war was good for women workers. In 1918, at the beginning of World War I, the United States Employment Service published lists of jobs that were suitable for women in order to encourage men in those occupations to switch to jobs that supported the war effort. “When the lists have been prepared…it is believed that the force of public opinion and self-respect will prevent any able-bodied man from keeping a position officially designated as ‘woman’s work,'” the Assistant Director of the U.S. Employment Service said in 1918. “The decent fellows will get out without delay; the slackers will be forced out and especially, I think, by the sentiment of women who stand ready.”

Since women were doing work that men would ordinarily do, the National War Labor Board decided they should be paid the same: “If it shall become necessary to employ women on work ordinarily performed by men, they must be allowed equal pay for equal work.” The same thing happened during WWII, as more women worked in munitions factors and the aircraft industry. During the war effort, equal pay was championed by unions and male workers, although not for entirely altruistic reasons—they were worried that if women were paid less for the same work, management could dilute male workers’ wages after they returned from the war.

After the war ended, the demand for equal pay seemed to lose some steam. In 1947, Secretary of Labor Lewis Schwellenbach tried to get an equal pay amendment passed that would apply to the private sector, arguing, “There is no sex difference in the food she buys or the rent she pays, there should be none in her pay envelope.” But as veterans needed work after the war and women were increasingly expected to stay in the home, Schwellenbach’s bid was ultimately unsuccessful.

National legislation was finally passed in 1963, when John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Law into effect, overcoming opposition from business leaders and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, who were concerned that women workers were more costly than male ones. When he signed the bill, Kennedy called it a “significant step forward,” and noted that, “It affirms our determination that when women enter the labor force they will find equality in their pay envelopes.” The next year, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, origin, color, religion or sex.

There have been more legal wins for female workers since then. The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 protected pregnant employees, and the Family and Medical Leave act of 1991 allowed parents regardless of genders to take time off. But despite the fact that women made up almost 58% of the labor force in 2012, they still made only 77 cents for every dollar a man made, according to the National Equal Pay Task Force. In 2009, President Obama chose the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act as his first piece of legislation, which restores some protections against discrimination that had been stripped in a 2007 Supreme Court case, and incentivizes employers to make their payrolls more fair.

But progress is still slow. Last year, a bill that would have made it illegal for employers to retaliate against employees who discuss their wages failed in the Senate.

Read TIME’s 1974 take on equal pay, here in the TIME Vault: Wages and Women

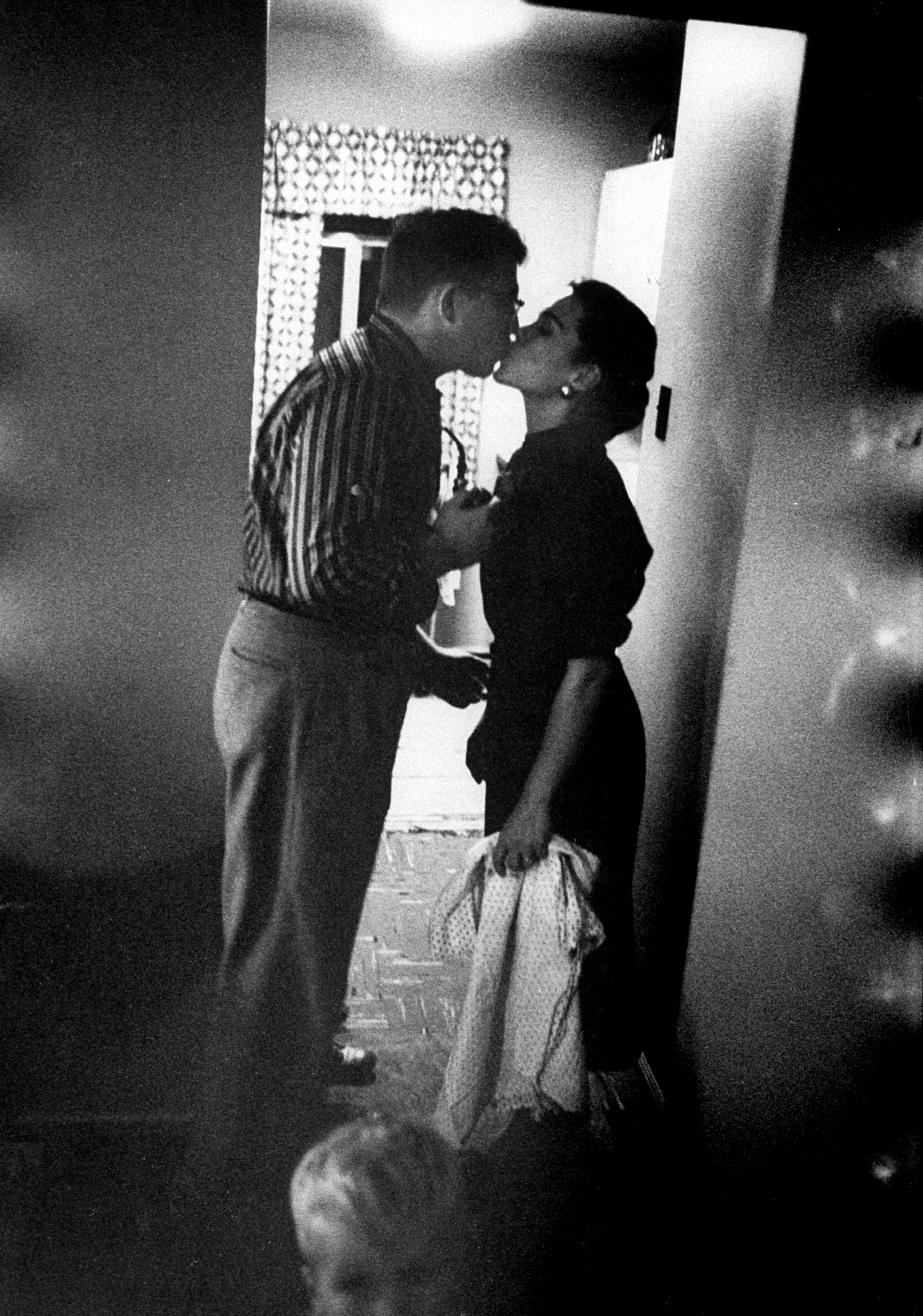

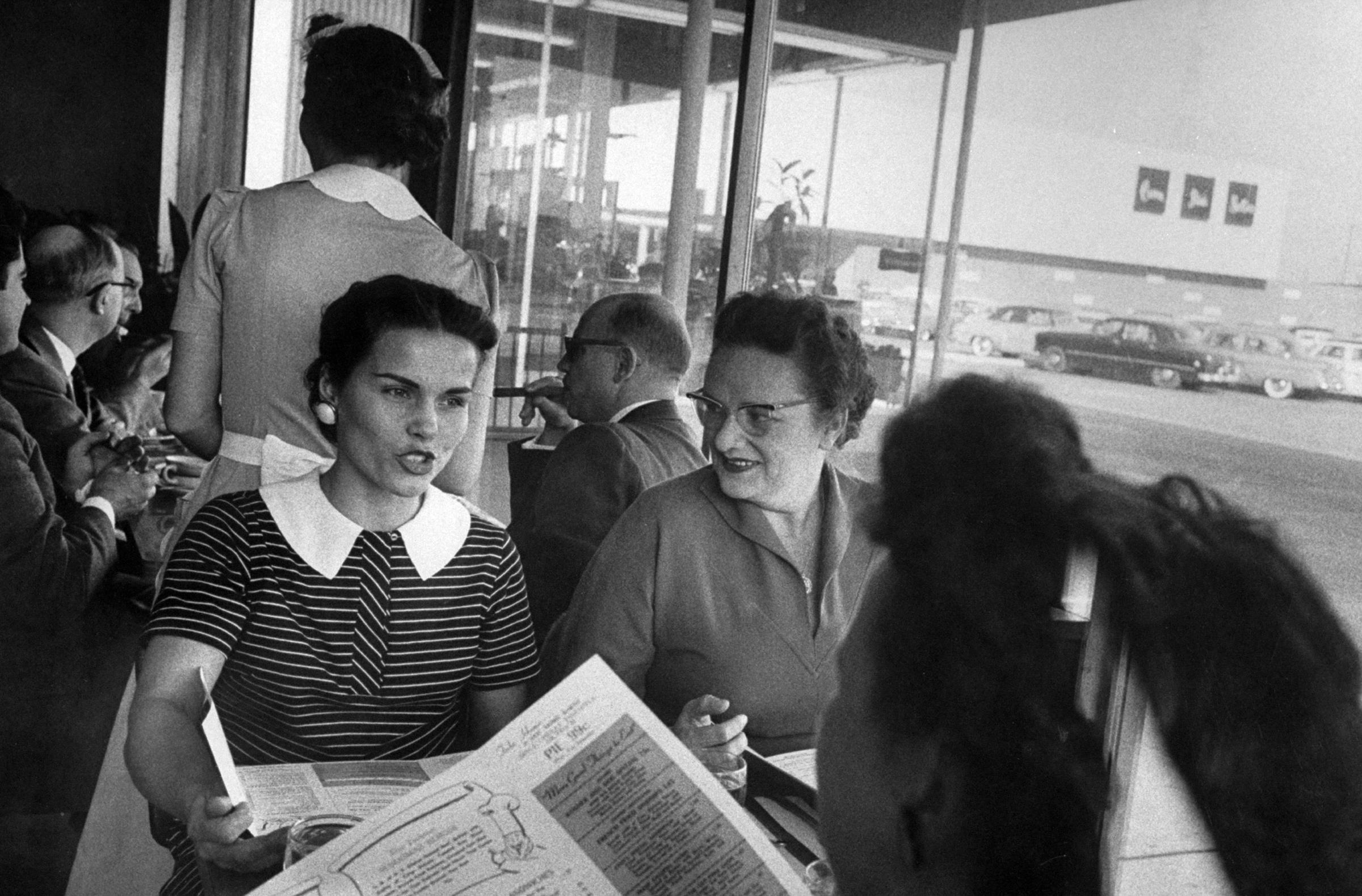

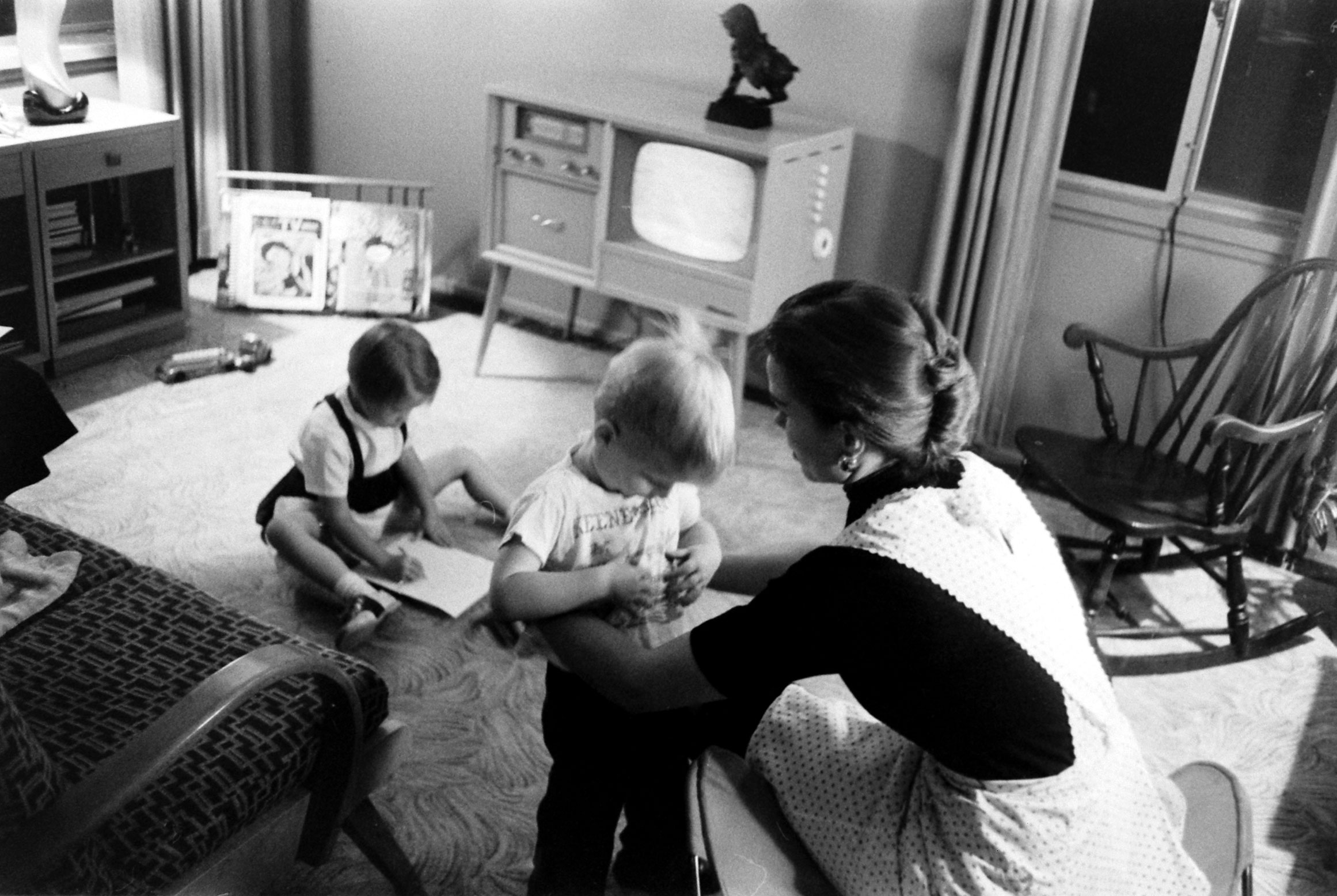

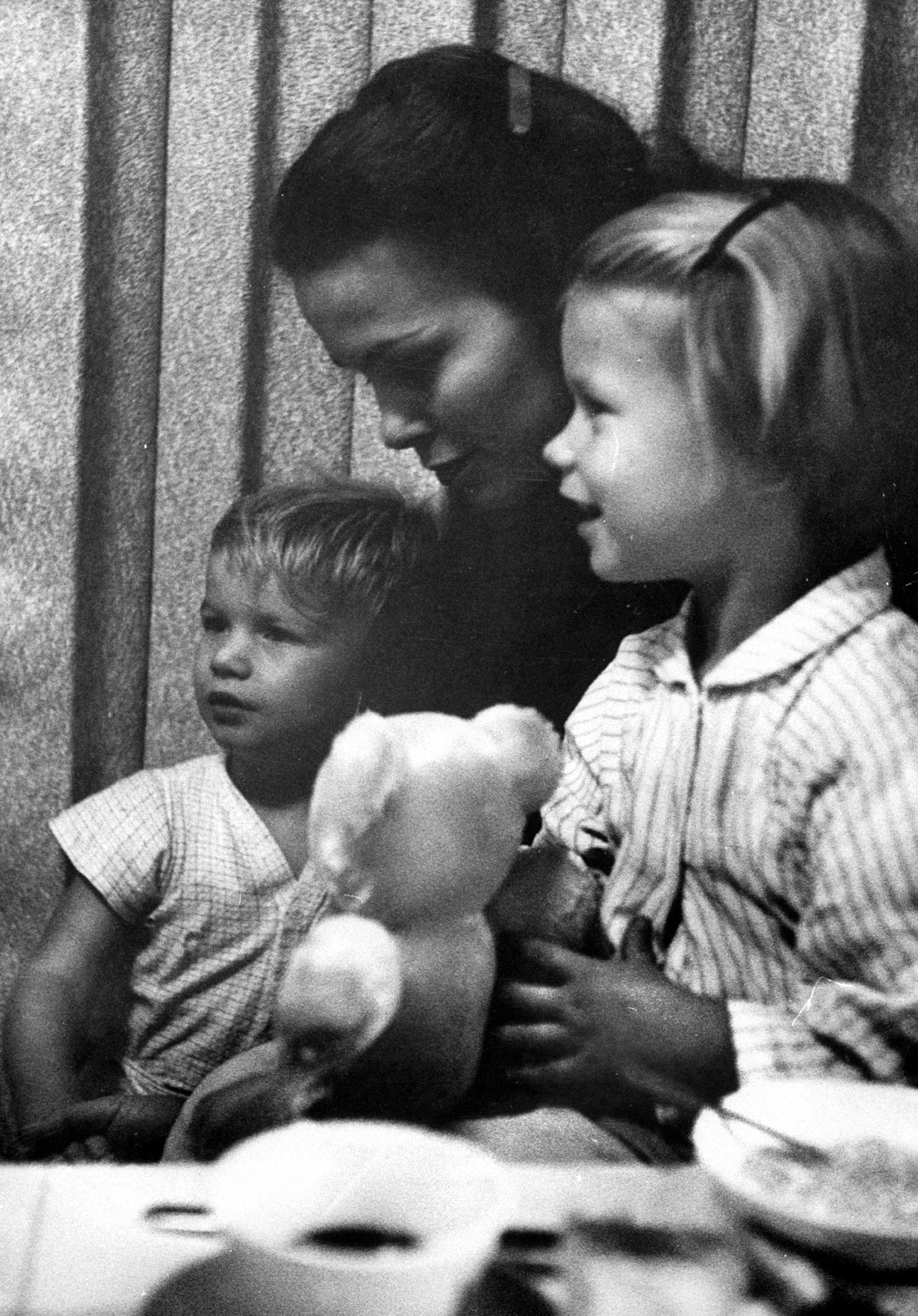

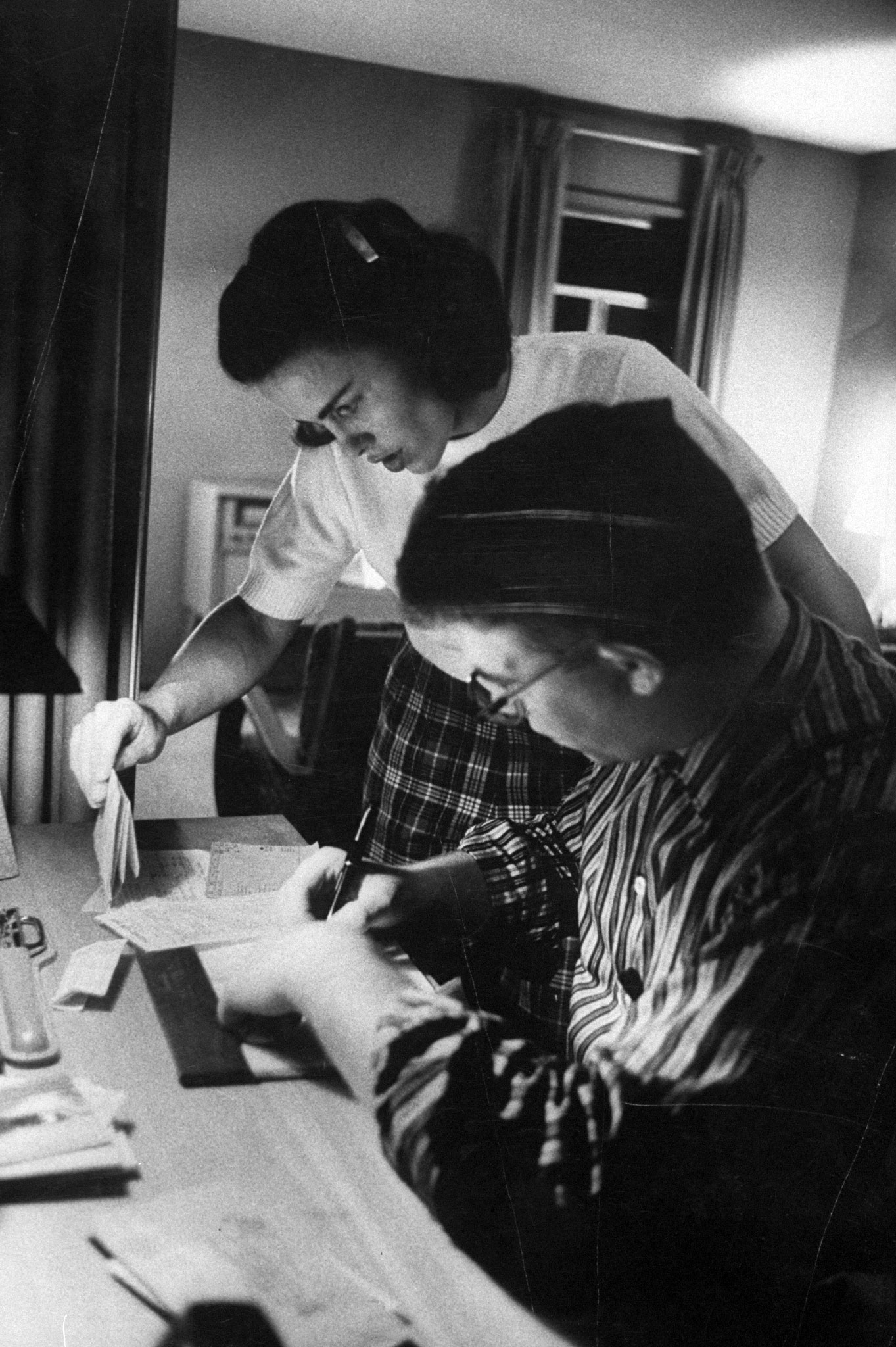

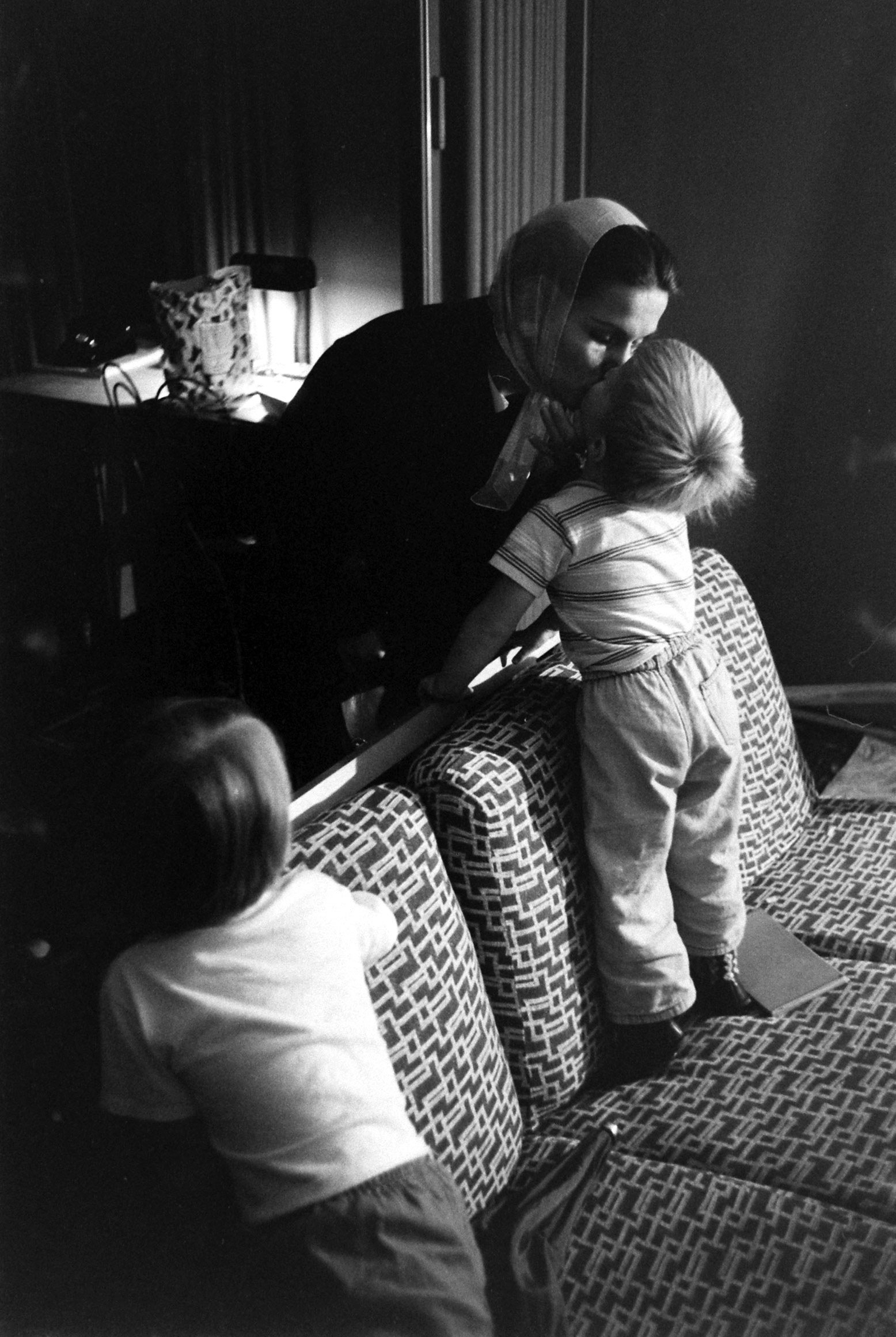

Life Before Equal Pay Day: Portrait of a Working Mother in the 1950s

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com