Since the Wilderness Act took effect in 1964, the United States government has protected more than 100 million acres of land for the purpose of conservation. About 8% of the continental U.S. is under protection, including natural treasures like Yosemite, Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon.

But while these efforts have preserved some of the country’s most unique scenery, other areas that may be even richer in animal and plant biodiversity aren’t being protected, finds a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The U.S. has protected many areas, but it has yet to protect many of the most biologically important parts of the country,” says lead study author Clinton Jenkins, a visiting professor at the Institute for Ecological Research in Brazil.

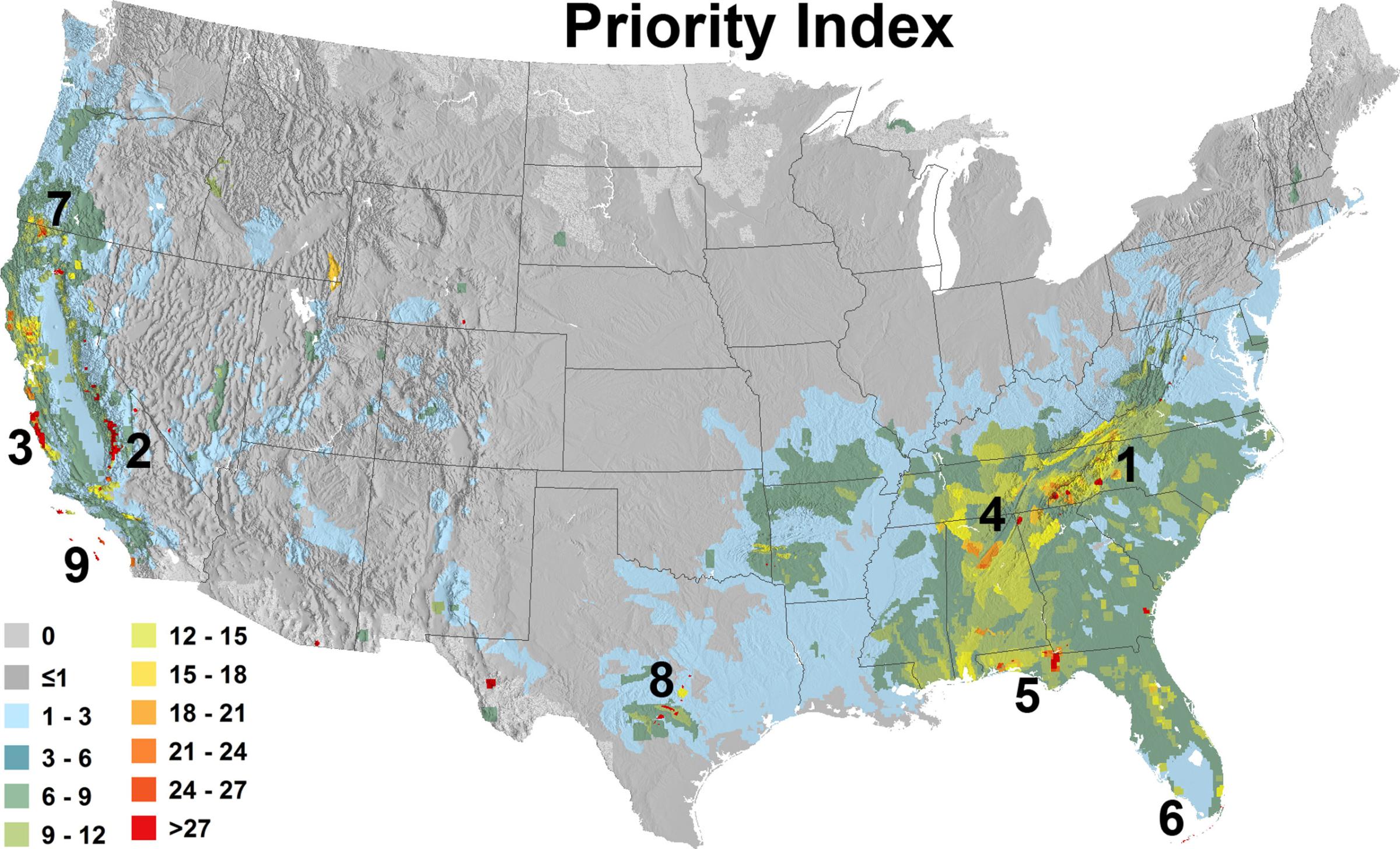

Jenkins and his team analyzed thousands of species of animals and trees to identify areas with the richest endemic biological diversity. Some of those regions, like the Everglades, are already protected, but many others are not. The areas most in need of protection are the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina, the Sierra Nevada Mountains and mountains on the California Coast, the study concluded.

“This is the most important scientific report of at least the last decade on the distribution of America’s parks and biodiversity, with implications for future policy on conservation and land use,” said study editor E.O. Wilson, Harvard University professor emeritus, in a statement.

Read More: Obama Moves to Protect 12 Million Acres of Alaskan Wildlife

Some of these regions might have been overlooked because of conservation policy that stretches back decades, says Jenkins. Land protection in the mid-twentieth century often focused on protecting “big beautiful landscapes, strange ecosystems and odd places,” rather than unique wildlife, Jenkins says. Conservationists also often found it difficult to enact protections on lands that could easily be used for other purposes like development or agriculture, even if they were rich in biodiversity. “There’s not as much competition for using that land,” Jenkins says.

Another factor in conservation policy has been the type of species facing extinction. Many conservation efforts have highlighted endangered mammals and birds while ignoring smaller and less visible reptiles and amphibians. The Southeastern U.S., for instance, is home to a wide variety of salamanders and fish, but has a lower percentage of its land protected than elsewhere in the country.

Jenkins says he hopes that conservation priorities will shift to include neglected regions and species, in part due to research like his. “If the U.S. doesn’t do something, they’re at risk of disappearing,” says Jenkins. “It’s not going to happen over night, but it’s up to us to make sure these species have a place to live.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com