The number of HIV cases found in a remote Indiana county has grown to 120, according to numbers released Friday by the state’s health department, after 79 cases were confirmed there over the last few months. Ten additional cases are awaiting confirmation.

The dozens of cases, described as an epidemic, are centered in Scott County, about a half-hour north of Louisville with a population of about 25,000. Indiana Governor Mike Pence declared a public health emergency there in March after dozens of cases of HIV were discovered.

An outbreak of HIV may seem odd in such a remote part of the country, but it’s been fueled by growing heroin and drug use in rural counties like this one. A number of Midwestern states have struggled with a recent uptick in drug and needle use, and Indiana specifically has seen an increase in the use of a powerful painkiller called Opana, which can be altered and injected. The number of deaths related to opioids like Opana rose from 200 a year in 2002 to 700 in 2012, according to the Indiana State Department of Health.

In this area of the state, there’s relatively weak public health infrastructure to prevent the infection from spreading. Scott County is just one of five counties serviced by a single HIV testing clinic, and the county’s relative isolation from a sufficient public health system can help explain the virus’s rapid growth, says Beth Meyerson, an Indiana University health professor and co-director of the Rural Center for AIDS/STD Prevention.

“The system isn’t working and isn’t strong enough from a public health perspective,” Meyerson says.

In a 2013 study by the non-partisan organization Trust for America’s Health, Indiana ranked last in federal funding per capita from the Centers for Disease Control. The national average spent per capita was $19.54. In Indiana, $13.72 was spent on each Hoosier.

Indiana has also seen an increase in Hepatitis C in many rural communities, says Meyerson, another warning sign that HIV may be spreading. According to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, about 25% of people who have HIV in the U.S. are co-infected with Hepatitis C.

On Thursday, state authorities stepped in. Gov. Pence allowed local officials to start a 30-day needle-exchange program in Scott County as a way to stop the outbreak. “I do not enter this lightly,” Pence said, according to the Indianapolis Star. “In response to a public health emergency, I’m prepared to make an exception to my long-standing opposition to needle exchange programs.”

MORE This Contraceptive is Linked to a Higher Risk of HIV

While dozens of cases have been reported, it’s likely that there are many more still unconfirmed. “I don’t expect these counties will remain the center of the epidemic,” Meyerson says. “I’m sure it’s going to be in other parts of southern Indiana, wherever our system is the weakest. We don’t know what we don’t know right now.”

Read next: At Least 120 Now Infected In Indiana HIV Outbreak

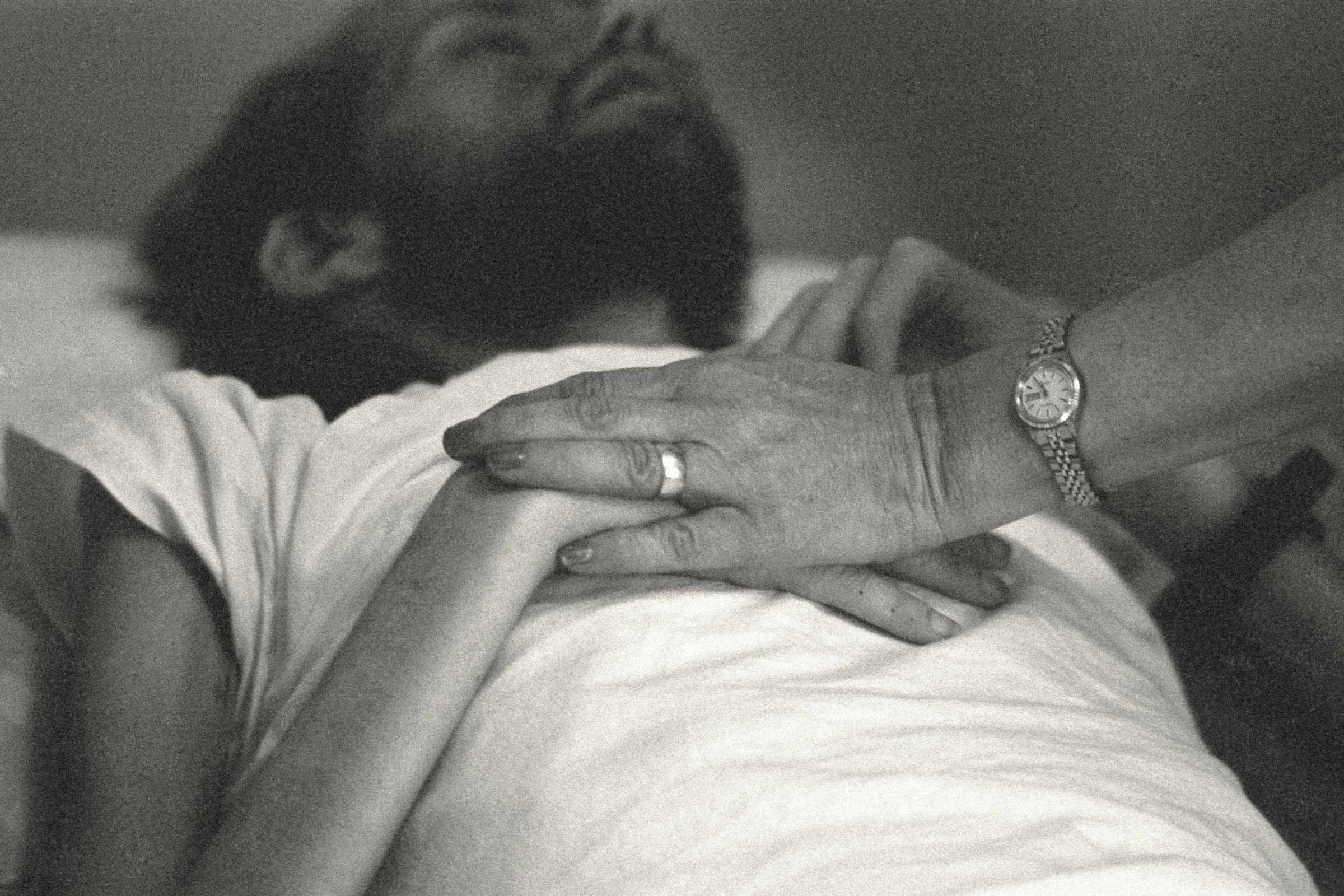

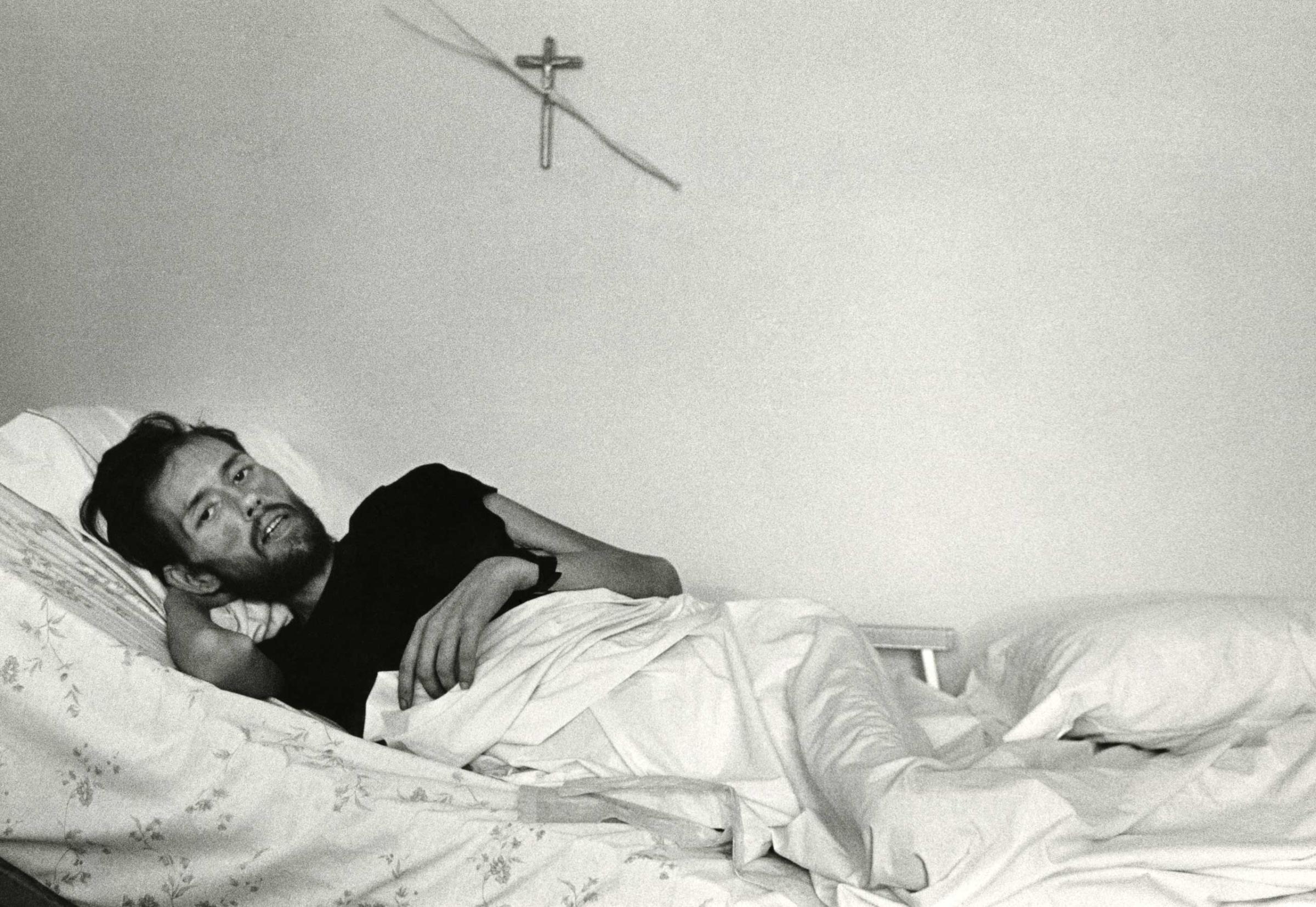

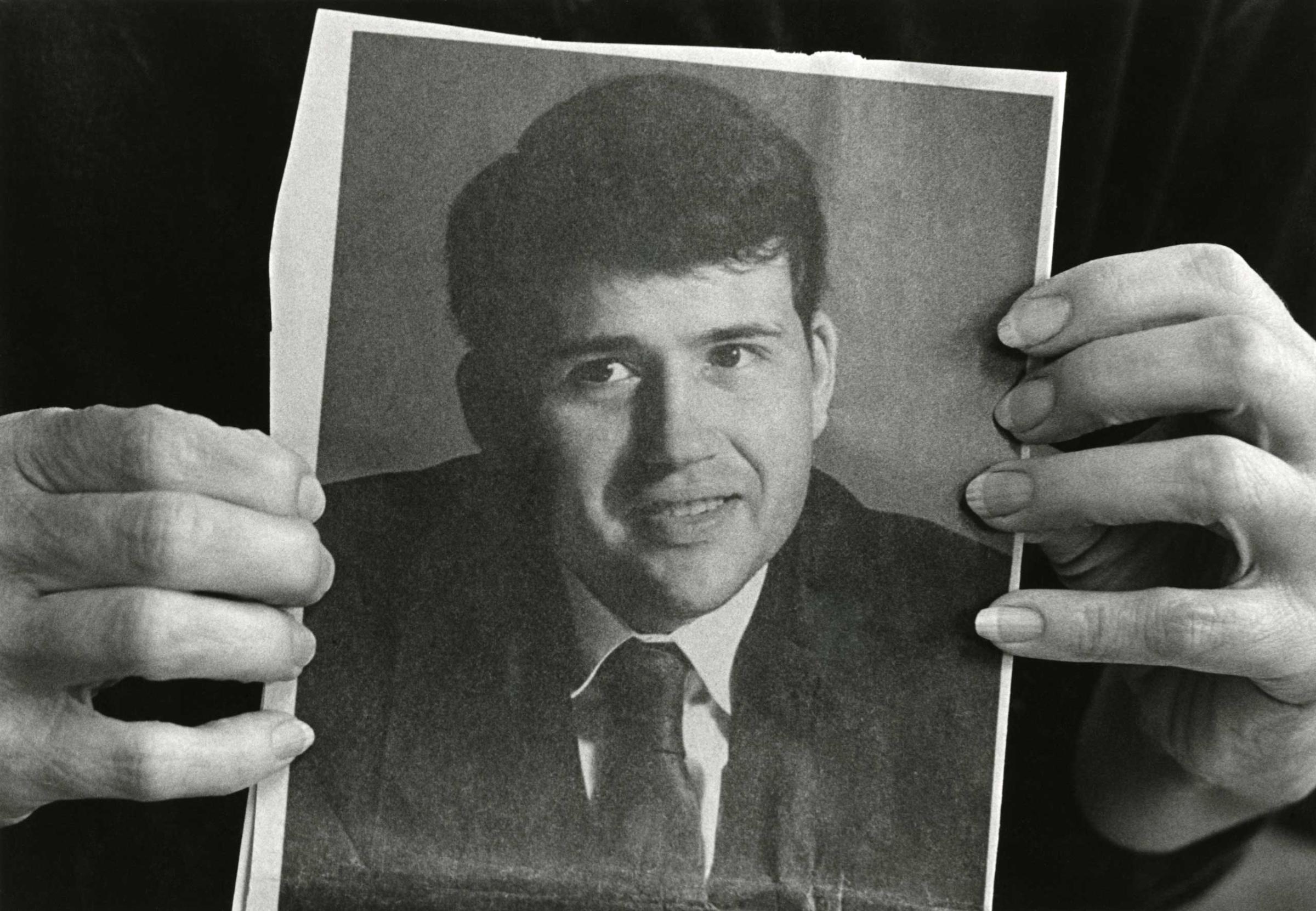

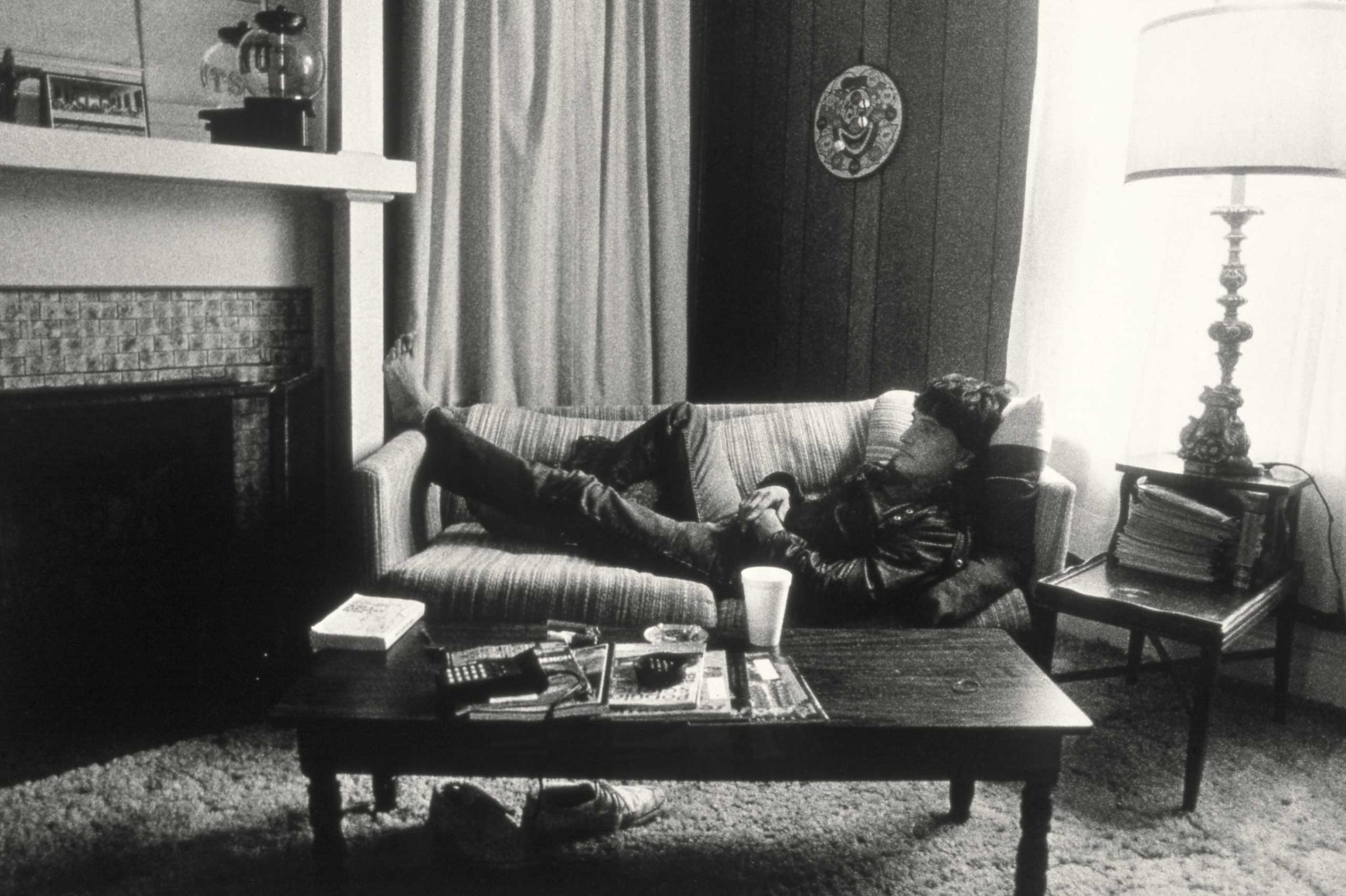

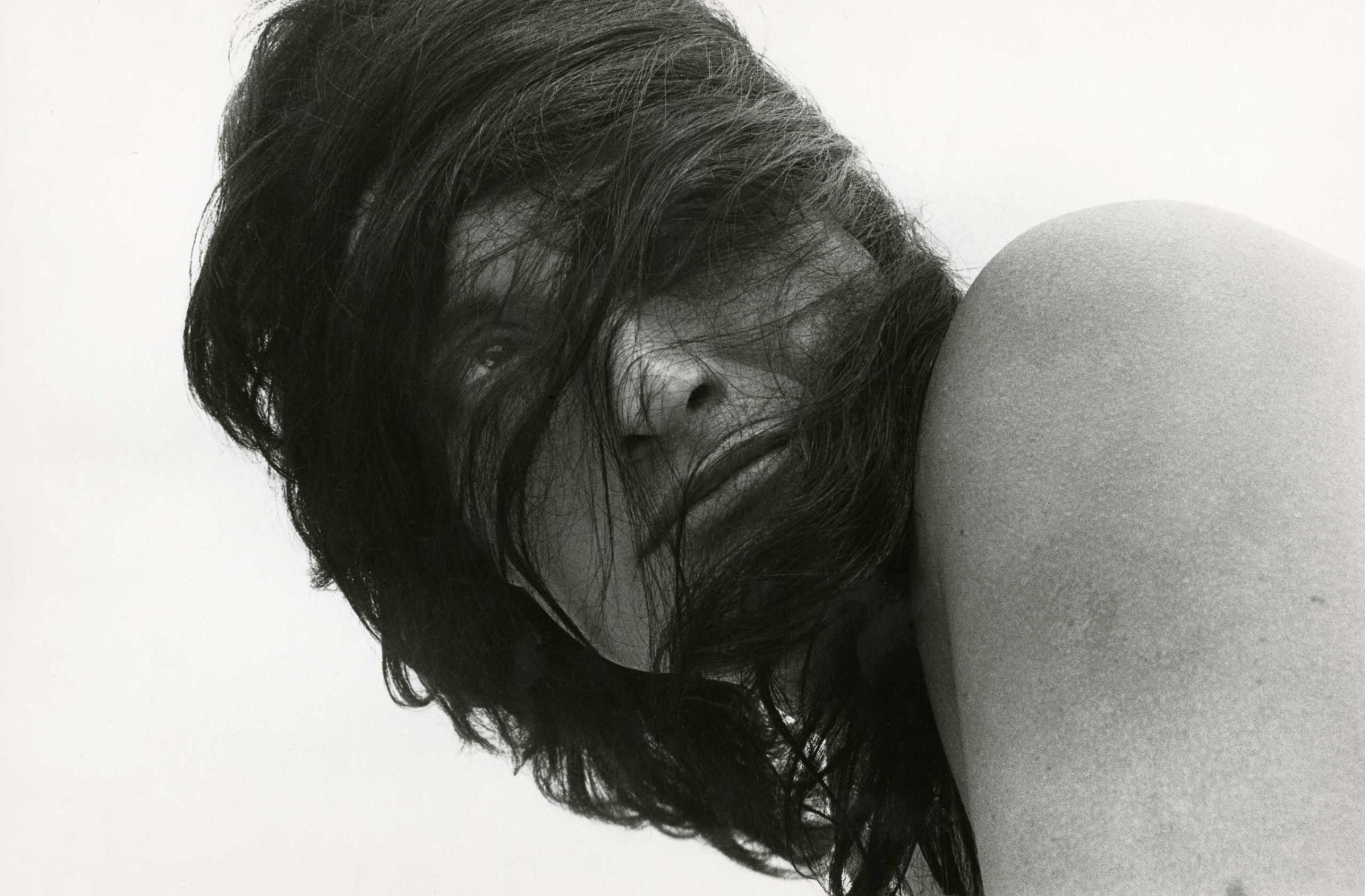

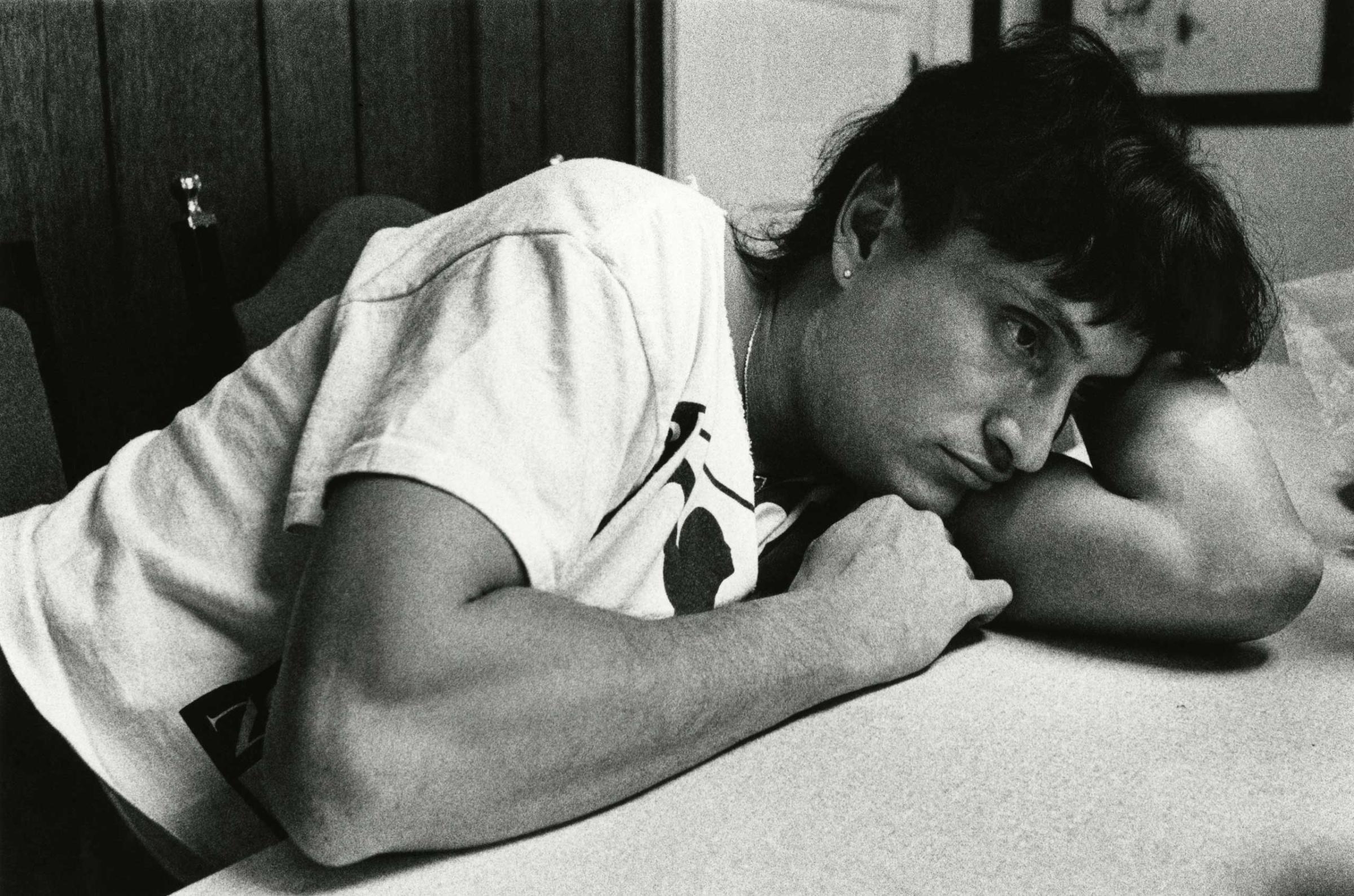

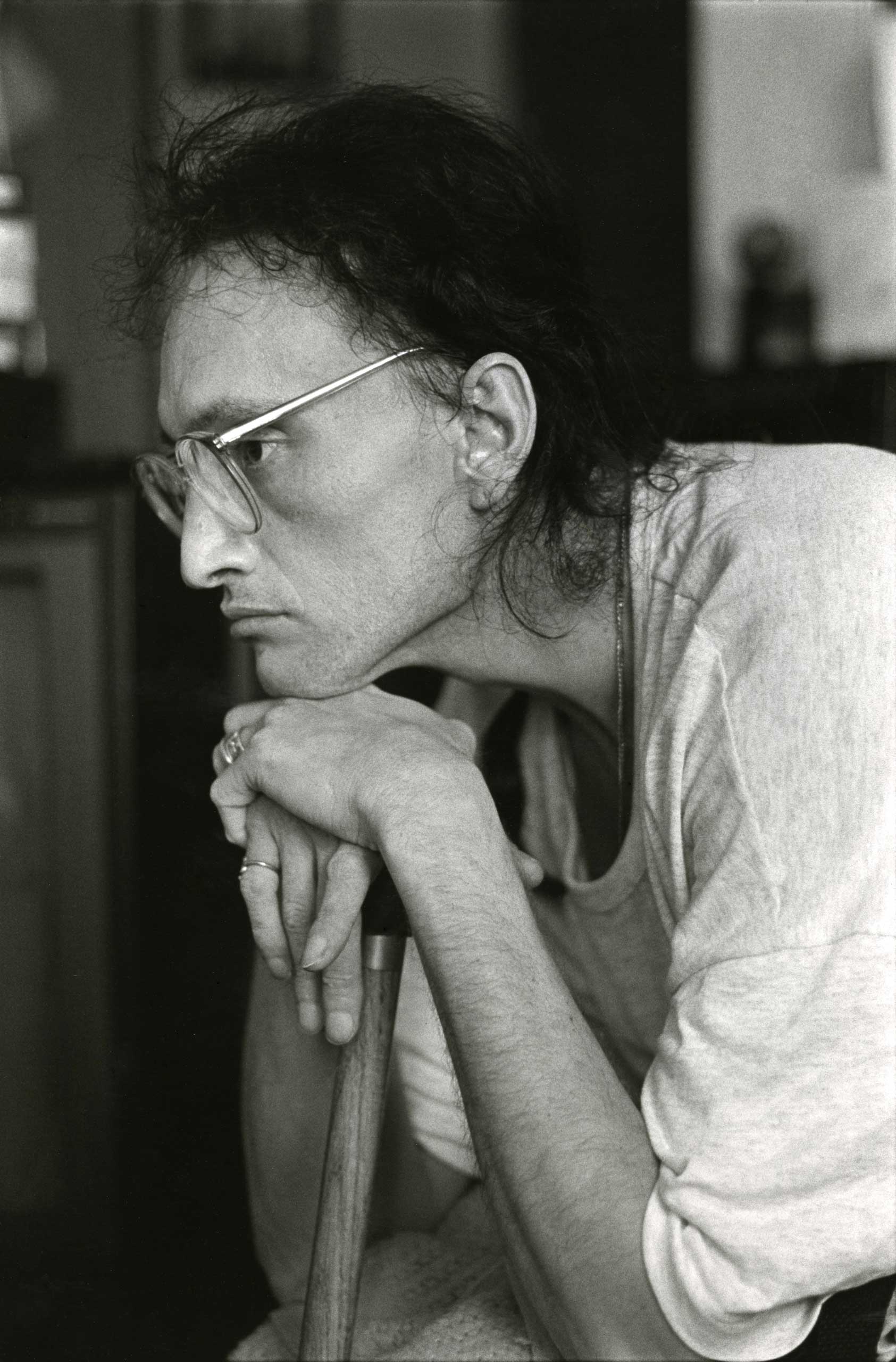

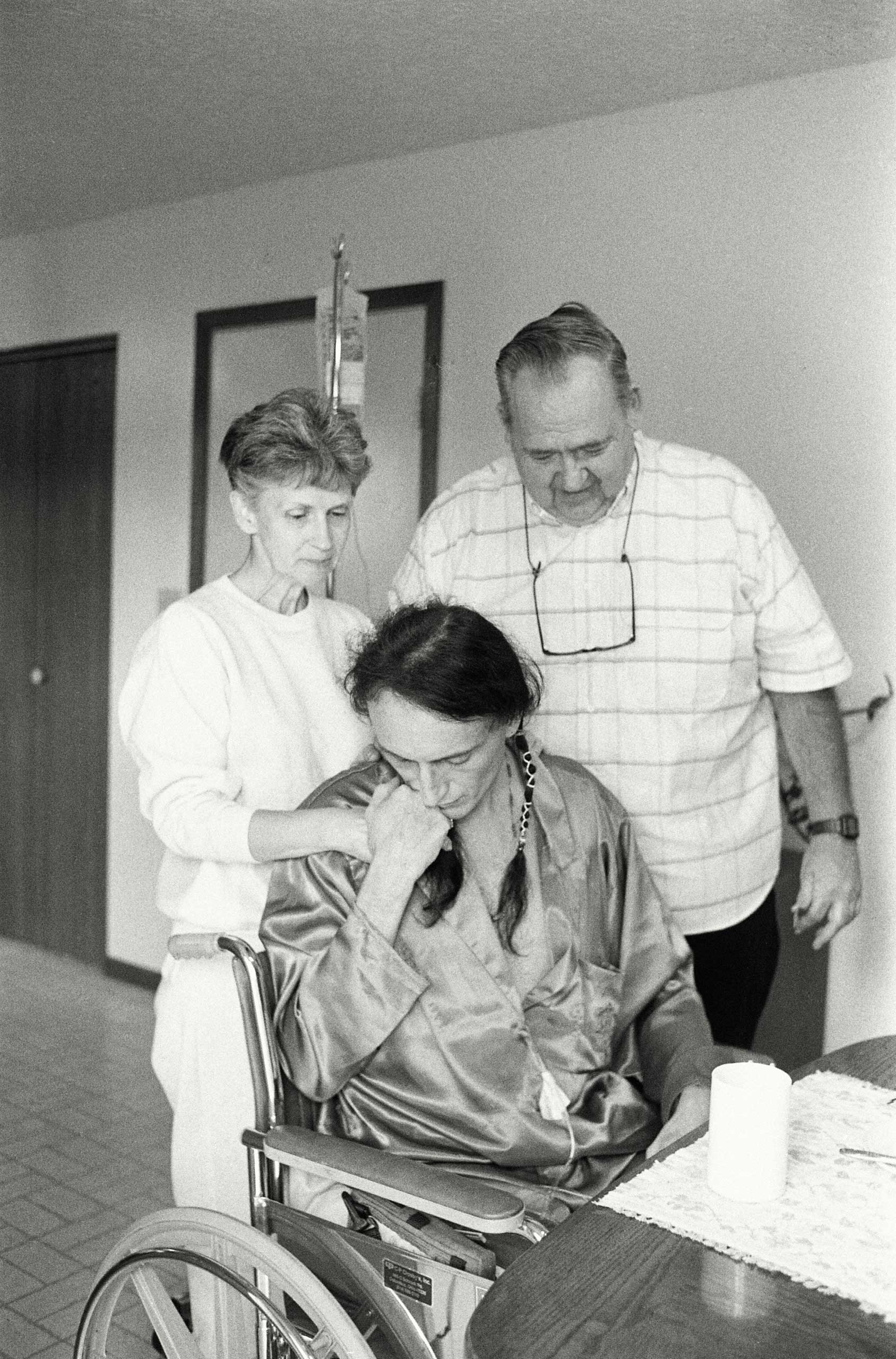

The Photo That Changed the Face of AIDS

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com