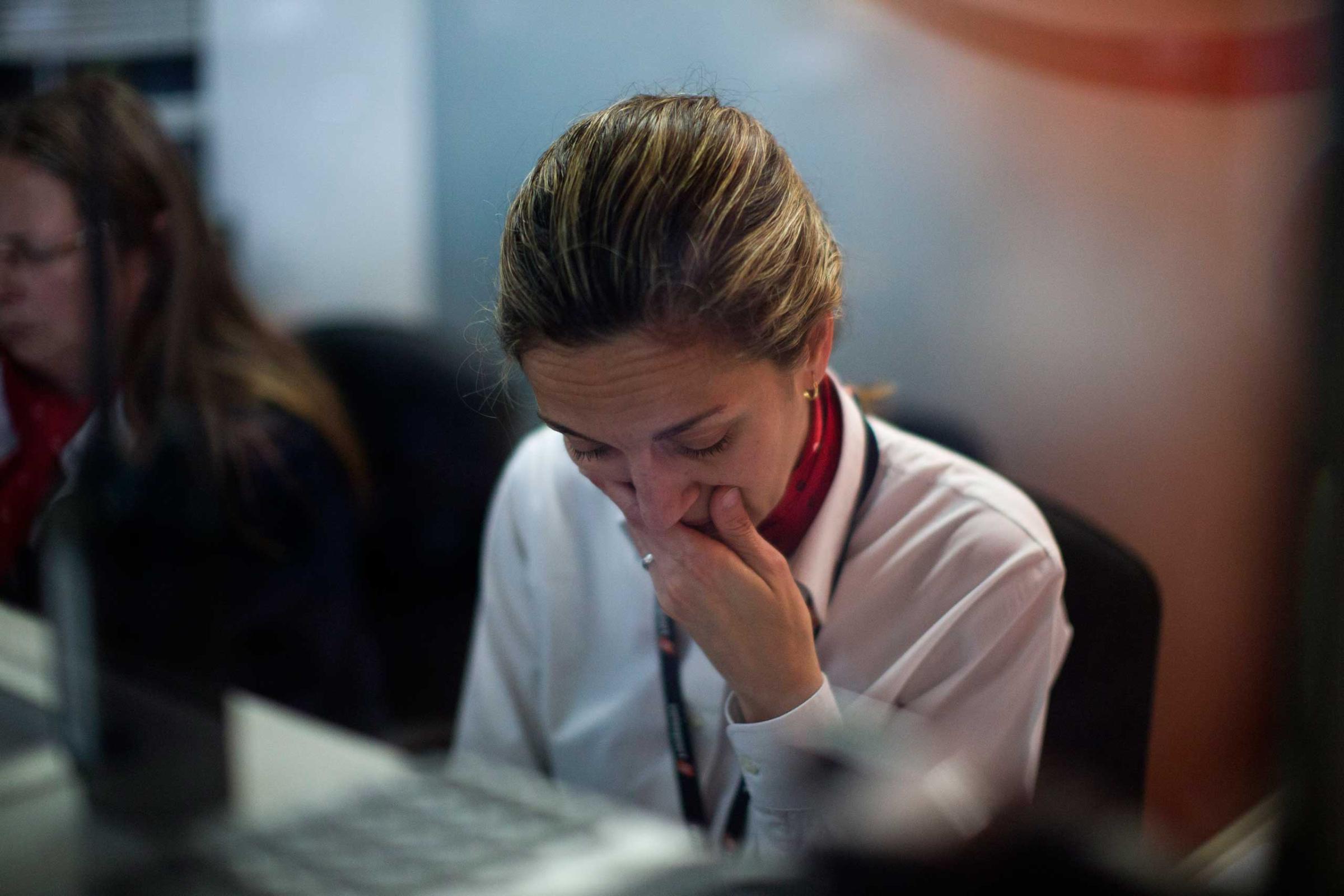

Officials said Thursday that the crash of Germanwings Flight 9525 appears to be a deliberate act by a co-pilot who locked himself in the cockpit and flew the plane into a mountain. All 150 people aboard were killed when the jet crashed into the French Alps on Tuesday.

Here’s everything we know so far about the unfolding tragedy:

What exactly happened on the day of the flight?

Germanwings Flight 9525, an Airbus A320, departed Barcelona en route to Dusseldorf on Tuesday morning. Around 30 minutes into the flight, the plane had reached a cruising altitude of 38,000 feet when it began to descend rapidly at a rate of 3,000 feet per minute. Ten minutes later, the plane crashed in a remote area of the French Alps. Initially thought to be a tragic accident, investigators now suspect the crash was a “deliberate” act by the co-pilot.

How did investigators reach that conclusion?

The plane’s black box audio recording, recovered from the wreckage, documents the pilot knocking loudly on the cockpit door as the plane descended. The co-pilot, Andreas Lubitz, can reportedly be heard breathing on the recording but did nothing to open the door. Screams can reportedly also be heard on the recording in the moments before the impact. Marseille prosecutor Brice Robin, who has played a key role in the investigation, said Thursday that the incident was due to the “voluntary action of the co-pilot.” It remains unclear whether the pilot tried to reenter the cockpit using a security code, Lufthansa CEO Carsten Spohr said at a news conference.

Who was the co-pilot?

Andreas Lubitz from Montabaur, Germany, had control of the plane at the time of the crash. The 27-year-old was a lifelong aviation enthusiast who joined a local flying club as a teenager, where he would eventually receive his flying license. He signed up with German carrier Lufthansa’s pilot program in 2008 and trained in Germany and Arizona. Spohr said Lubitz took a several-month-long break from training, but re-entered the program without issue. Germany’s Bild newspaper reported that Lubitz had spent the time in psychiatric treatment.

Lubitz joined Germanwings as a pilot in 2013 and temporarily worked as a flight attendant while waiting for an opening as a co-pilot. He had 630 flight hours on the A320 under his belt at the time of the crash, making him a relative rookie.

Was it suicide, terrorism or something else?

Investigators have said unambiguously that they believe the crash to be “deliberate,” but have declined to go much further — and have avoided calling an act that killed 149 others a suicide. Lubitz had no known link to terrorism, Robin said. None of the passengers had connections to terrorist organizations either, according German Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière. Documents uncovered by German officials in a raid of Lubitz’s house suggest that he may have suffered from mental illness and hid it from his employer. Investigators found a sick note for the day of the crash that had been torn up. Another document indicated that aviation authorities required him to undergo regular medical checkups, though it’s not clear whether for mental or physical health issues.

Still, not everyone is holding the co-pilot responsible just yet; German pilots told TIME that it’s premature to blame Lubitz before a full inquiry has been completed. Even though the investigators said the crash was intentional, they admitted having no idea about a potential motive. “We have no indication what could have led the co-pilot to commit this terrible act,” Spohr said.

Witness Scenes From the Plane Crash in the French Alps

Do regulations exist to prevent a pilot doing this?

On U.S. airlines, a flight attendant must enter the cockpit when either the pilot or co-pilot leaves for whatever reason. Since Tuesday’s crash, at least five airlines—including Germanwings parent company Lufthansa—have announced they would adopt new rules for cockpits.

Does the airline have a decent safety record?

Germanwings, a low-cost carrier wholly owned by German airline Lufthansa, operates throughout Europe and has maintained a clean safety record since its founding in 1997. None of its airplanes had been involved in a crash prior to this week, the company said.

And what about the aircraft?

The A320 has a reputation as a workhorse for commercial airlines, carrying passengers around the world on medium-range routes. Crashes are not unknown; an A320 operated by AirAsia crashed into the Java Sea in January, and a U.S. Airways A320 made the famous “miracle on the Hudson” crash landing in 2009. But before you read too much into that, aviation experts say the A320 is among the safest planes in the sky. Only 11 of the model’s nearly 80 million flights since it entered service in the 1980s have been fatal, according to Air Safe. That’s six times fewer than the Boeing 747, for example.

Who was aboard?

The flight carried 144 passengers and 6 crew members. About half of the people aboard were German, and 25% of the passengers were Spanish. At least 13 other countries are represented in the remaining passengers, including three Americans—mother and daughter Yvonne and Emily Selke from Virginia, and Robert Oliver Calvo, an American citizen born in Barcelona. Also among the dead were 16 German high schoolers, a newlywed couple, and a pair of renowned opera singers. Death was instantaneous for the passengers aboard, Robin, the Marseille prosecutor, said on Thursday.

What might happen next?

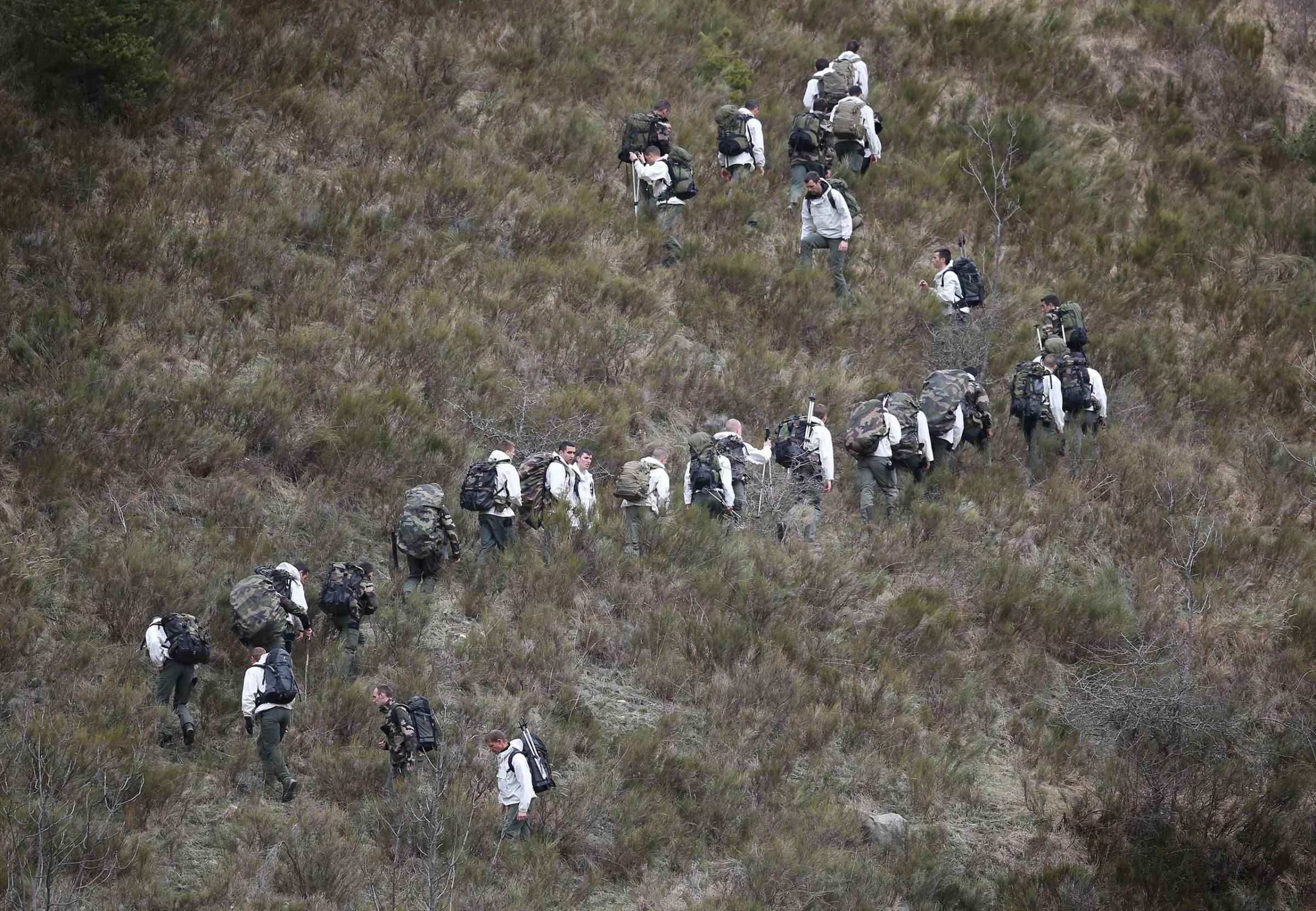

There are still plenty of questions to be answered; it’s unclear whether the pilot locked outside the cockpit entered a code to get back in or whether Lubitz manually prevented him from entering. FBI investigators have joined the inquiry into the crash, alongside German, French and Spanish officials. Late Thursday night, a team of investigators searched the co-pilot’s Montabaur home and emerged with several bags, a large cardboard box and what appeared to be a computer. Meanwhile, the search goes on, high in the French Alps, for a second “black box” flight data recorder that might be able to reveal more about the plane’s final moments.

Read next: How Pilots Are Screened for Depression and Suicide

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com