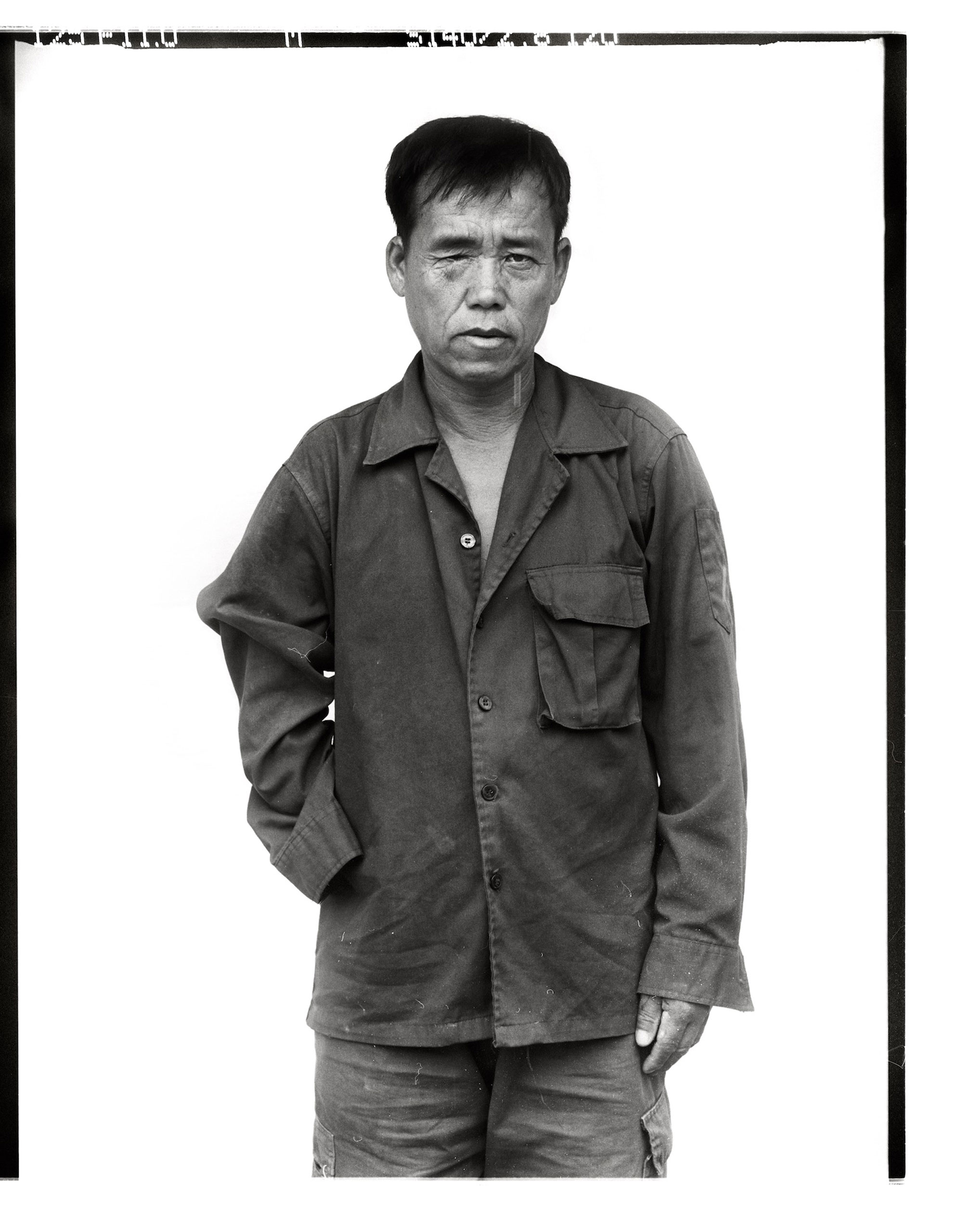

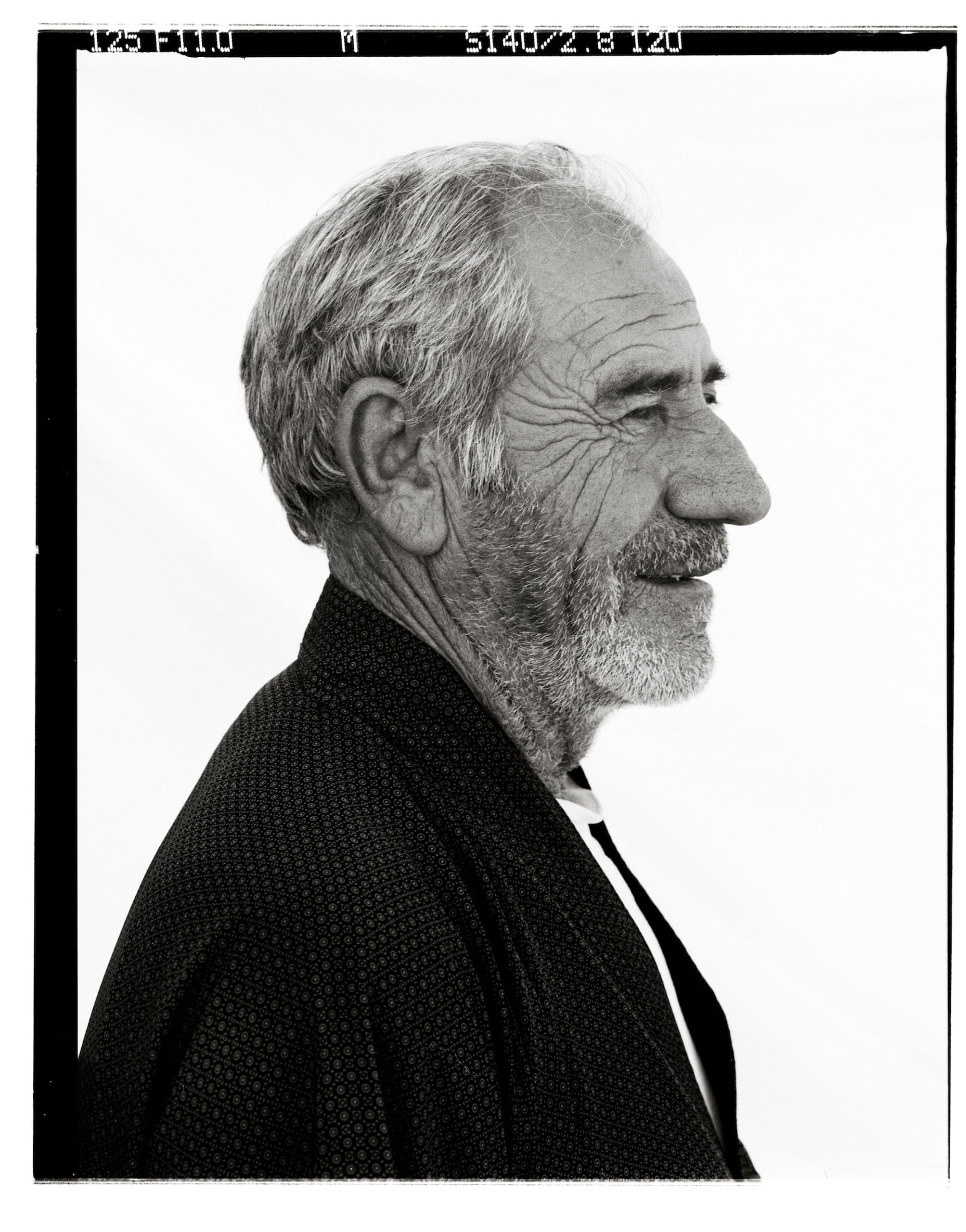

In 2011, photographer Giles Duley began a project that would document the lasting effects of war on people living in cities and towns across the globe where the fighting had ended many years, even decades ago.

That year, while patrolling in Afghanistan with American troops, Duley stepped on an Improvised Explosive Device. The blast nearly took his life; he lost both legs and an arm. After a year in the hospital and nearly 30 operations, Duley returned to photography with a new determination to finish his project, which he calls Legacy of War. The project encompasses 14 countries and comprises photographs, original poetry and music.

Last month, he launched a Kickstarter campaign to help fund the project, which you can contribute to here. Below, TIME Multimedia Editor Mia Tramz caught up with Duley as he continued his work on the project from Cambodia.

TIME LightBox: What’s the scope of the project and the idea behind it?

Giles Duley: The idea came to me I guess four or five years ago. A lot of my work has been documenting the effects of conflict over the years. One of the things I noticed was that there was a lot of commonality between the stories that I heard, and so I became interested in trying to bring all these different stories together. I was actually going to Afghanistan to start the project when I got injured, so I thought it would never actually happen. My plan was if I could get working again, I would return to doing this project.

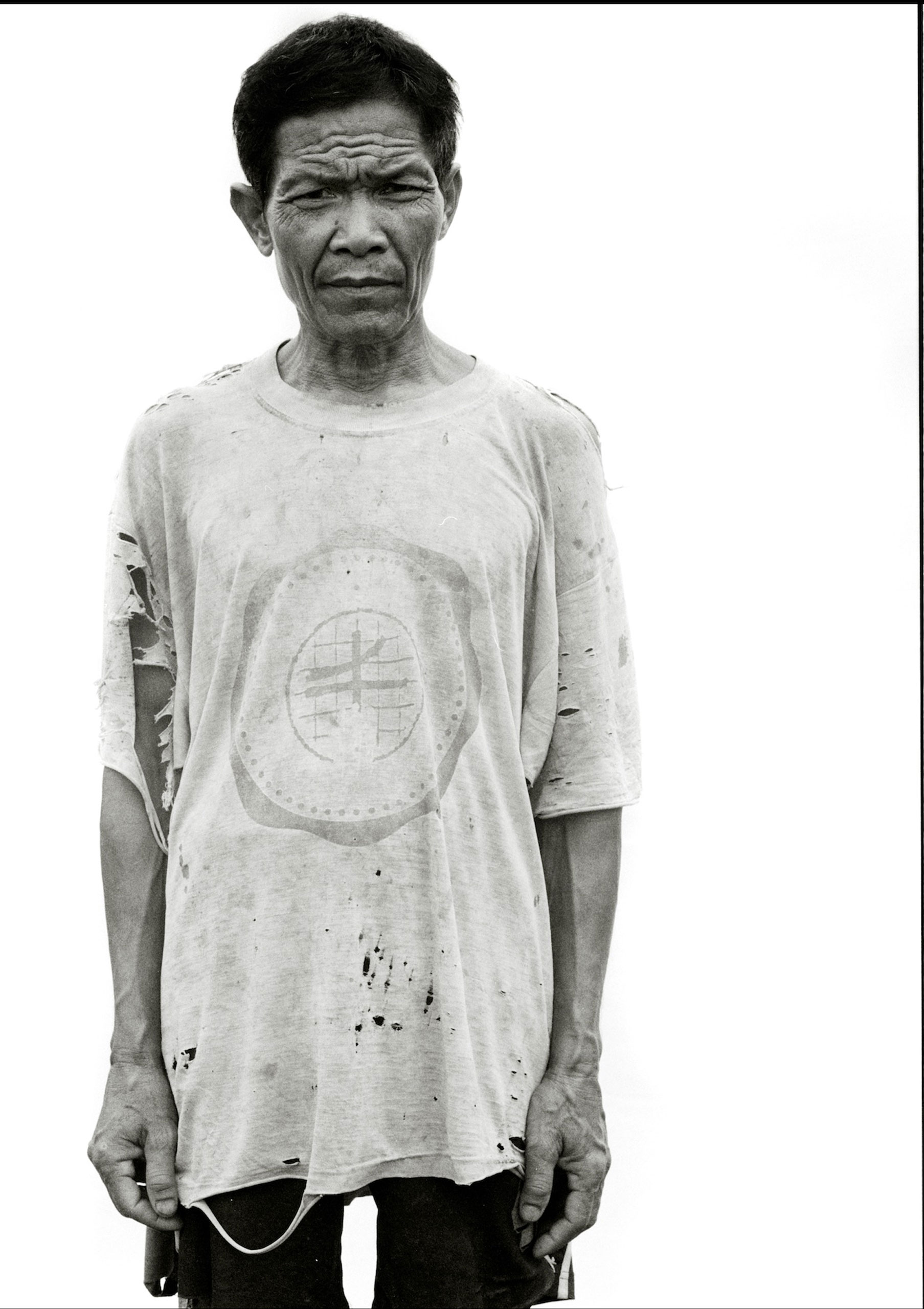

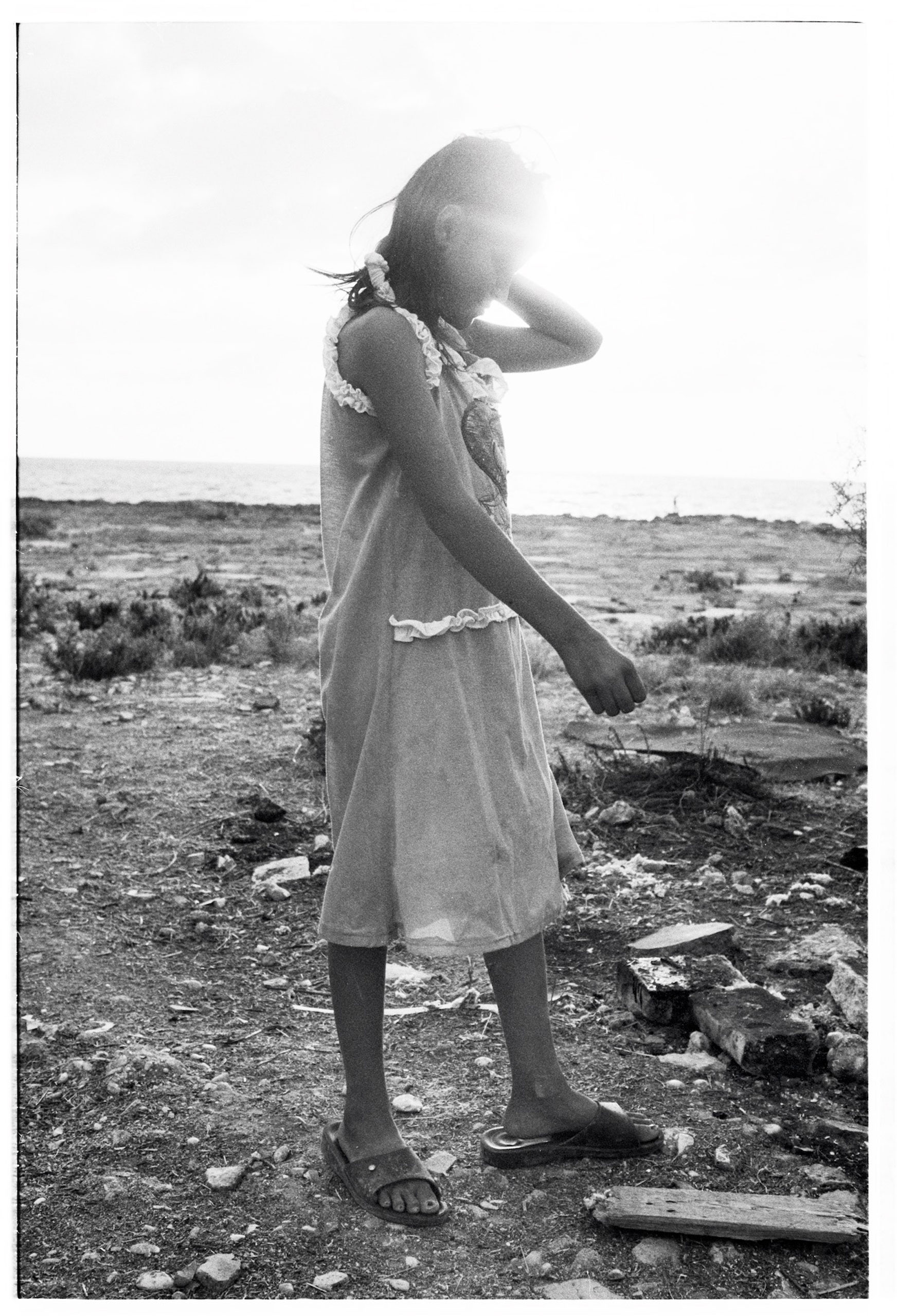

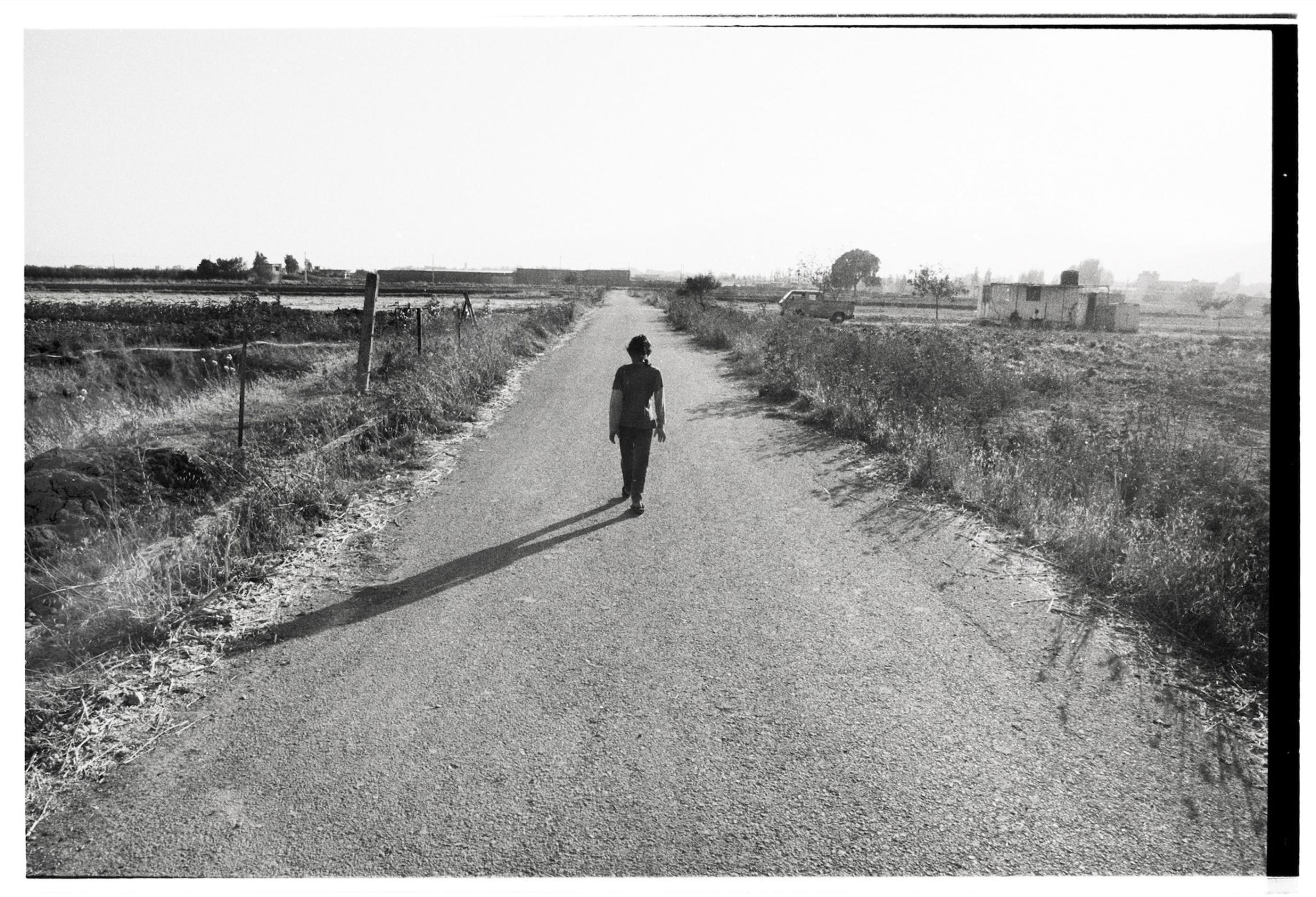

The thing that really strikes me is that a war doesn’t end when a peace treaty is signed. In school, as you’re growing up, you’re always taught about the dates of a particular conflict. And I was interested [by] what happens after this final date; what happens when the conflict is supposedly finished. Because what I’ve experienced in my work was that the war is not over if people are still dying from it, if they’re still injured, if their lives are still impaired by it.

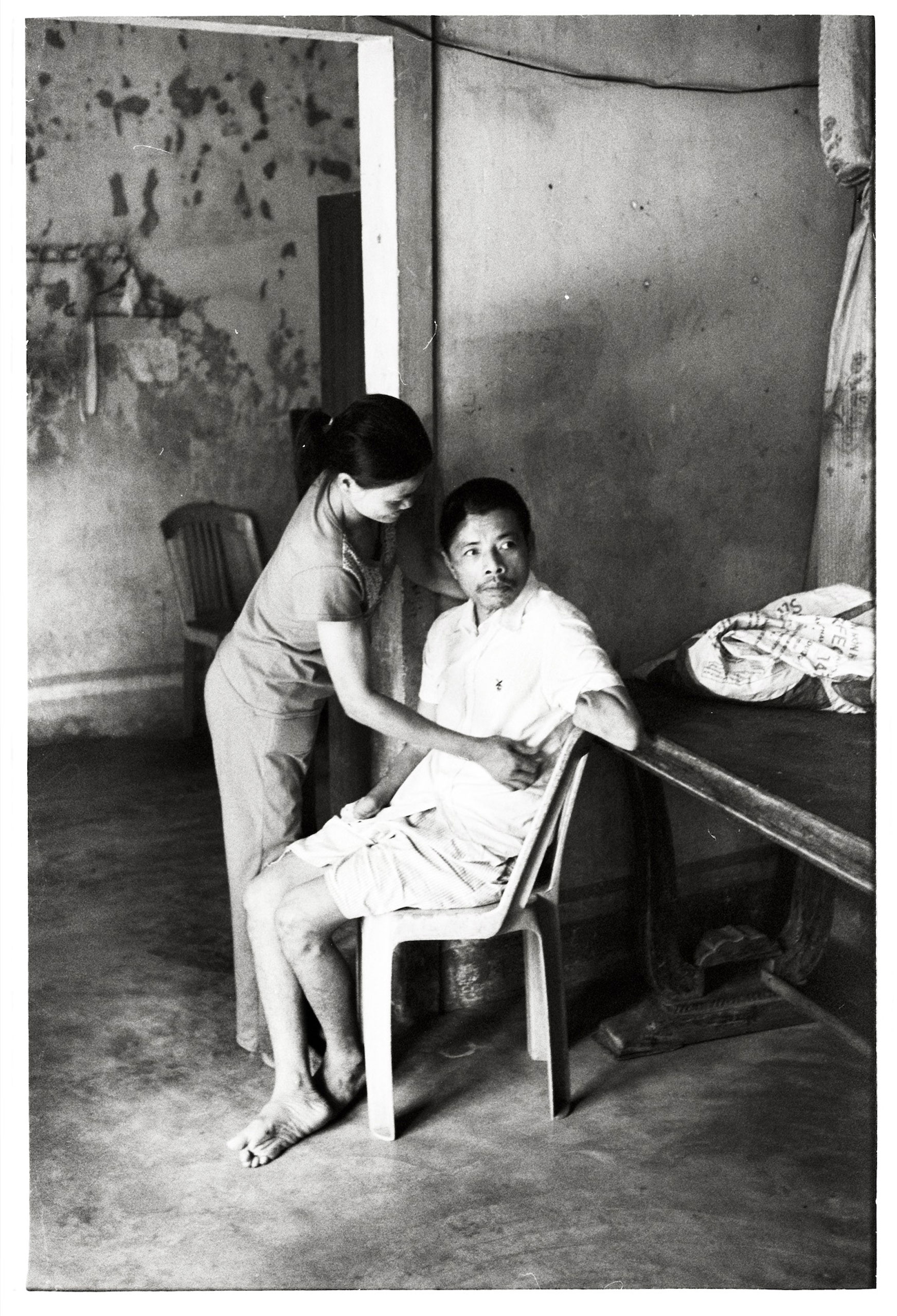

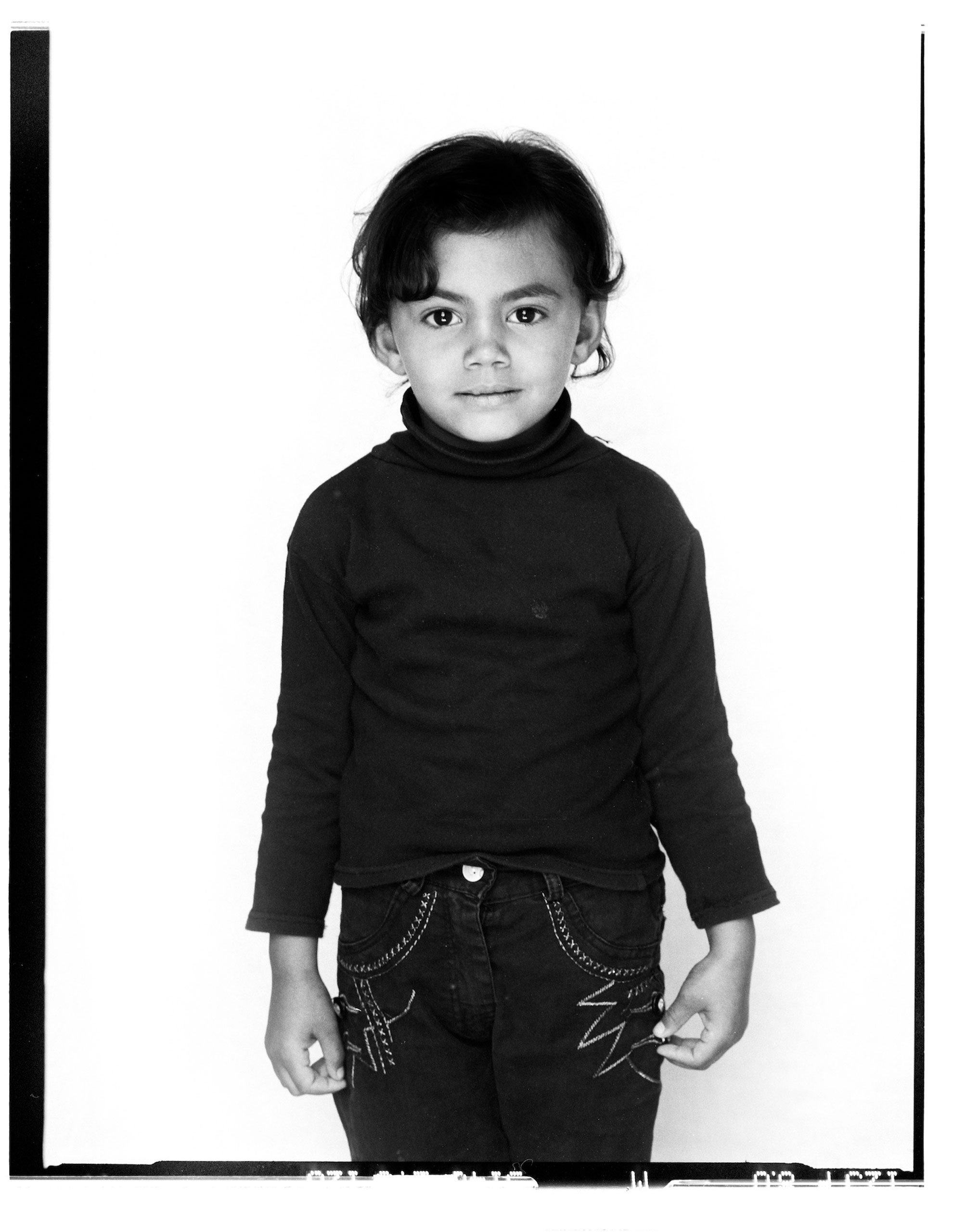

My idea was to try and bring together stories from approximately 14 countries, showing various themes that kind of crop up in post-conflict countries. That might be land contamination from land mines, from UXOs and it might be the effects of things like Agent Orange or depleted uranium. But it’s also looking at the physical effects on people who are living with injuries, and people living with the psychological trauma of conflict. I wanted to bring all these different stories together and just get people to reflect on the fact that conflict doesn’t end when a peace treaty is signed.

TIME LightBox: Which countries will you be covering and how did you choose them?

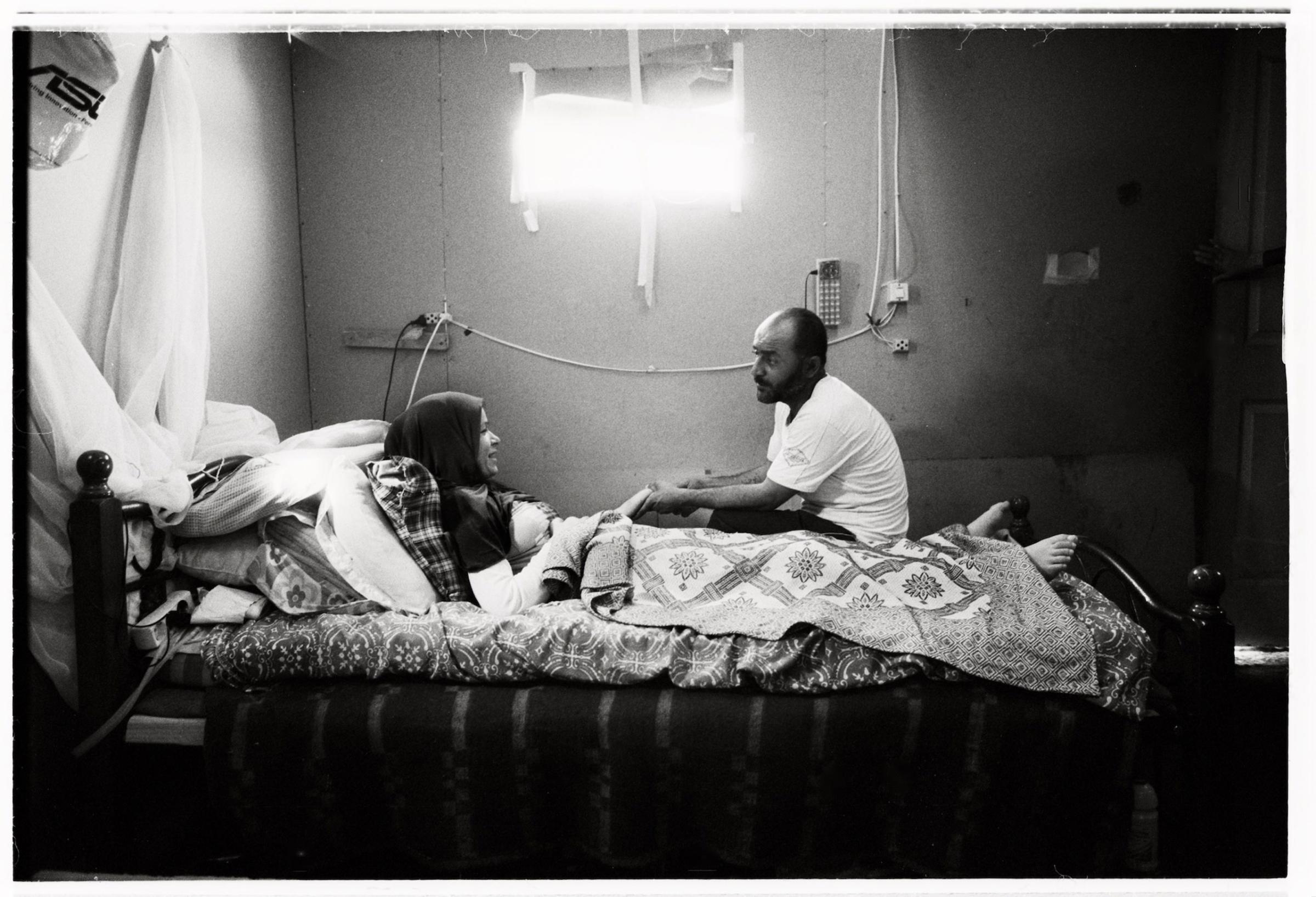

Giles Duley: One of the things I kind of want to do is to bring together stories that may be a little bit more familiar to us with stories that are less familiar. Hopefully, by bringing them together, you get to understand the similarities. In the United States, I wanted to look at the effects of trauma on former combatants, especially soldiers from [the] Vietnam War, how their lives have been affected. The same in the U.K. looking at injured servicemen and [those] with PTSD. Then it’s countries like Vietnam with Agent Orange and UXO; Cambodia, Colombia, Laos and other countries like it by land mines. I’ll be doing stories in Angola, which has a huge legacy of war; in Congo or the DRC, I’ll be looking at the effects of sexual abuse in both men and women. In Northern Ireland, I’m looking at the effects of the troubles, [which have] caused poverty and other social issues.

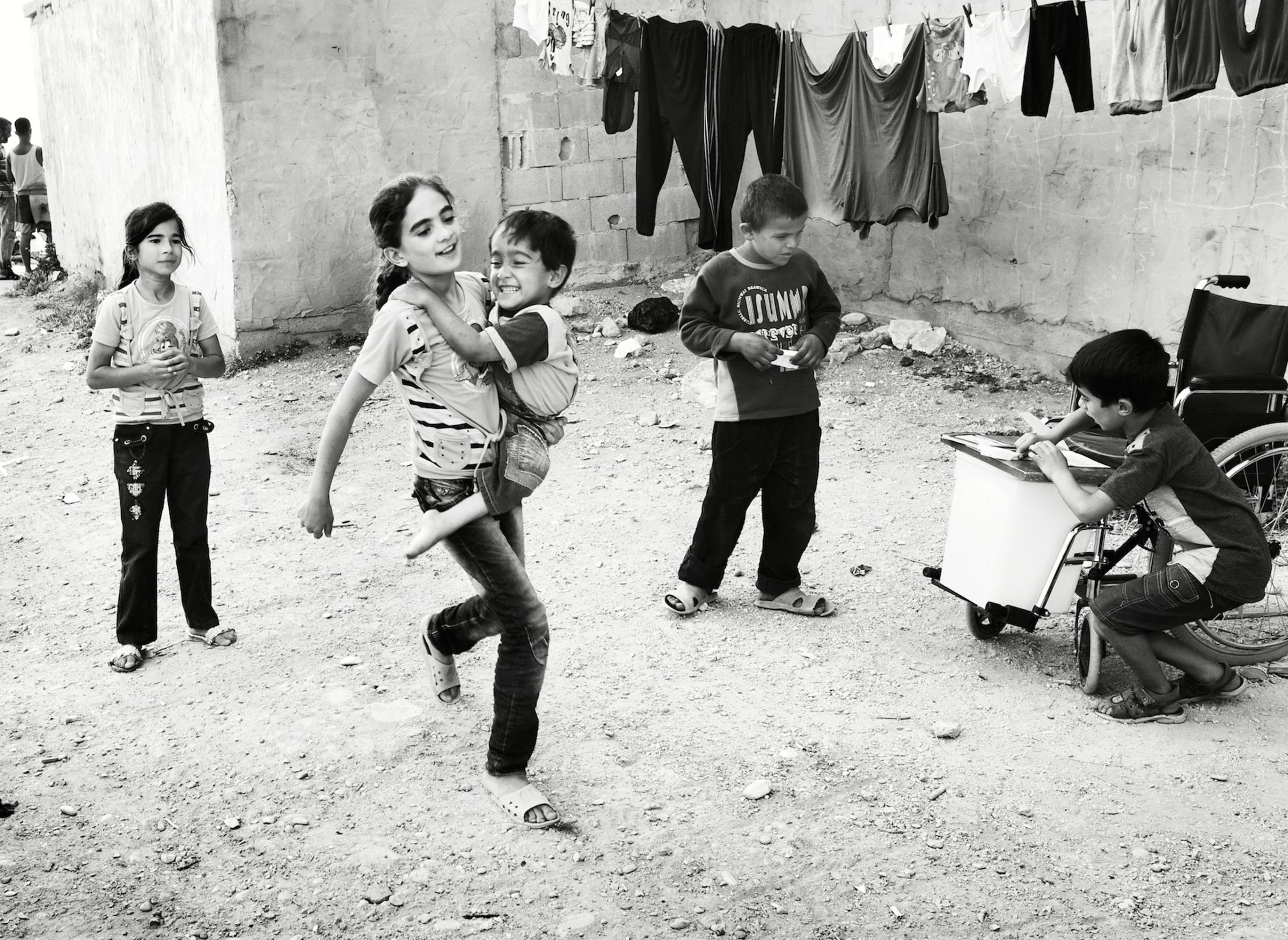

Other countries [will include] Gaza, [where] I’ll be looking at the long-term effects of conflict there. I’ve already done a story on the refugees in Lebanon, a country which really had two tiers of refugees from war. I’ll be looking at refugees in Sahel Sahara. It’s a vast cross-section of stories.

TIME LightBox: How did you arrive at the aesthetic for this project?

Giles Duley: I actually decided to use film for this project — a mixture of 35 mm and medium format. The main reason for film is that I wanted the images to both have a timeless feel and to serve as documents. Many of the photographs will reflect the period when the conflict happened and at the same time, a print made from a negative has a sense of true documentation. In a period when many question the role of Photoshop and other manipulation in documentary photography, I wanted to return to a simpler process.

TIME LightBox: Outside of the photography, what other components are you working into the project?

Giles Duley: I want this to be more than just a set of photographs. As a child, I was really influenced by the poets of the First World War and the black-and-white photographs covering the Vietnam War. They were the two things that really changed my opinion as a very young teenager about conflict. I grew up as a kid [thinking] that I wanted to join the army. I was fascinated by military history. But as I say, it was reading this poetry of people like Sassoon and Wilfred Owen and looking at the photographs of people like Don McCullin that really galvanized something in me, that made me realize the true consequences of war.

I’m very interested in the educational component. I realized that schools are still studying poetry from the First World War. So what I want to do is update that and get poets and musicians writing about current conflicts and their long-term consequences. For me as a photographer, I hope that the poetry and the music will add a different dimension to the work, so that it’s more accessible to people.

TIME LightBox: What’s your process working with these musicians and poets? Are they seeing the photographs you’re making from those particular parts of the world, or are they just writing or creating from their own experiences, or a mix of both?

Giles Duley: Anybody that’s working with me on this project will either be traveling with me at a later stage in the project, or it will be a process of me meeting them, showing them the photographs, and probably most importantly sharing the testimonies of the people who are photographed.

TIME LightBox: What has surprised you most since you started working on this project about what you’re finding?

Giles Duley: I don’t know if it surprised me, but what I’m becoming very aware of is just the enormity of how conflict affects life. [For example], in Vietnam, Laos and Lebanon and Cambodia — you start to look at one story, and immediately that opens up 10 other stories. It’s often in less expected ways or [something] you just don’t think about. Some of the stories are more obvious, like land mines, etc. But when you look at the long-term impact of a child that was born to a woman who was raped, that is a real legacy of war. And they live with that legacy for all of their lives — the psychological trauma of people affected by war is something that is not often talked about or documented, but whole generations of civilians have been traumatized by conflict.

TIME LightBox: Can you talk about where you see the project living when it’s finished and in what form?

Giles Duley: This is a project that has four phases. The first phase is the photographic phase, which is to go out there and document the initial stories. The second phase is to work with poets and musicians to give more depth to the stories. The third phase is then looking at how that body of work comes together through exhibitions and a book. For me that stage is very important because the exhibitions have to be in public spaces. They have to be in places where people interact with these stories who wouldn’t normally go to a photographic gallery.

And I’m also very interested in taking the project back to the countries that I’ve photographed. One of the things that most surprised me is how interested people are in the other countries I’m photographing. People in Northern Ireland are asking me about the people in Rwanda. The people in Vietnam are very interested in stories that I’m going to be doing in Angola, for example.

One of the key elements is, as well as having the photographs exhibited in the public spaces in Western countries, it’s for the exhibitions to return to the countries where these stories first came from, so the stories are shared. Because that’s what it’s all about. It’s about sharing stories. I have no judgments, I have no opinions. I’m merely going out there to try and gather the stories of people affected by conflict and to share those stories.

And then the final stage, the fourth stage, will be educational. And that’s about taking it to schools. It’s about getting it on the curriculum, [so that when] people are taught the historical facts of a conflict, they’re also taught about how a conflict continues to affect people [long after it’s over]. That’s how I see it developing. And hopefully, in the end, it will be something that will kind of take on a life of its own and I can step back and people can continue to share these stories.

TIME LightBox: Your story is also woven into this. How has your experience informed your approach to this project and how it has been integrated into it?

Giles Duley: No matter what I choose to do for the rest of my life, I will live with the scars, both physically and mentally of what happened. So it’s given me a great understanding. But I think more than that it’s kind of focused my ambition and determination to carry this project through because, as I say, every day now I live with a reminder of what conflict does.

It has opened up communication with a lot of people that may have been more suspicious of why I was doing this story; people who see my personal experience and can relate to it. I guess weirdly, although I may be a lot slower as a photographer now and it may be a bit harder for me to work, there’s probably not a photographer in a better position to actually tell these specific stories about the legacy of war.

TIME LightBox: What do you see as the biggest challenges in getting this project done?

Giles Duley: The biggest challenges on a personal level are the travel, the work. I have no legs and I’ve got one hand, and I travel on my own to do this work. It’s not easy. I must admit last year when I found myself in paddy fields in the rainy season in Laos, trying to carry all my cameras and a backpack and my legs getting stuck in the mud, I was thinking, “O.K., who came up with this idea?” [Laughs.] So the obvious challenges like that are there, that in a weird way as I say, also drive me on to complete the story.

Aside from that, obviously this is a project that I’m self-funding. It’s something that I think is important. A lot of NGOs and nonprofits and charities are helping me with the stories. I have years and years of working with NGOs and they’ve been fantastic in supporting this project. So the likes of MAG, which is a de-mining charity; Handicap International; UNHCR; Emergency, which is an Italian NGO; and Find a Better Way, which is another land-mine charity, have all been supporting it. But at the end of the day, I have to find a way to finance these stories, or at least finance the physical costs of the photographic side of it.

The project really I think for me is the defining project of my life. It will probably be the last major overseas project I do because it’s simply so physically draining and difficult for me. But I am determined to carry this out to the utmost of my ability.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Giles Duley is a freelance photographer and an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society. Follow him on Twitter @gilesduley.

Mia Tramz is a Multimedia Editor for TIME.com. Follow her on Twitter @miatramz.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com