In August 2014, a small number of children began turning up at emergency rooms around the country with symptoms of severe respiratory disease.

“Our hospital was overflowing,” recalls Dr. Sam Dominguez, a microbial epidemiologist at Children’s Hospital Colorado, in Aurora.

From the last week of August through the first three weeks of September, the hospital admitted 325 patients with respiratory symptoms, compared to an average of 130 during the same period the previous two years. “This disease was unprecedented for that time of the year,” says Dominguez.

Soon, it was discovered that many of the children were suffering from a specific strain of enterovirus: EV-D68. Many children who get enteroviruses have no symptoms at all; others develop what amounts to a nasty flu. But in this new outbreak, some kids were turning up with weak or paralyzed limbs, stumping doctors.

When the first case of sudden and unexplained partial-paralysis turned up at his hospital, Dominguez says the situation was unusual but not completely unheard of. Two weeks later, another child showed up with limb weakness and paralysis. The following week, there were four more cases. “We were very worried,” says Dominguez. The hospital called the health department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for insight.

The CDC reached out to public health authorities in other states and sure enough, states across the country were reporting bizarre cases of children coming in unable to move their limbs. From August 2014 to early March 2015, 115 children in 34 states have been diagnosed with what authorities are calling acute flaccid myelitis (AFM).

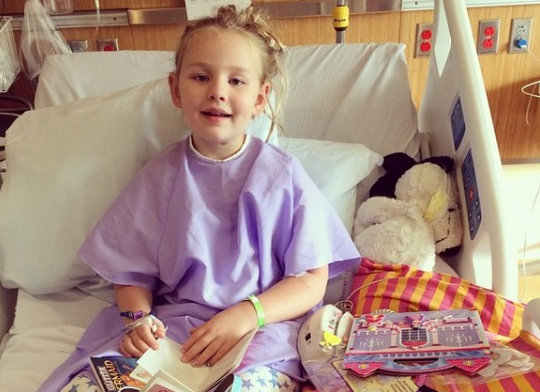

One of them is an 8-year-old named Bailey. Bailey’s mother, Mikell Sheehan, says that a few days after the family came down with what she describes as a bad cold, she discovered her daughter collapsed in the bathroom in their Oregon home, unable to move her leg.

In December, in California, Megan and Ryan Barr noticed their 6-year-old son Ryder was playing with only his left hand because his right arm felt funny. “It’s hard to explain to a six-year-old what’s happening to them,” says Megan.

One problem for doctors is that the sudden onset of paralysis among children, while rare, happens from time to time with other ailments, including West Nile or Guillain-Barré syndrome. Sorting between the possible causes—and deciphering what’s normal and what’s cause for concern—can be difficult, but experts agree this recent cluster is out of the ordinary.

“The short answer is yes, I think the cluster [of AFM] is connected,” says Dr. Jim Sejvar, a neuroepidemiologist with the CDC investigating AFM. “One of the challenges is there are a lot of different reasons kids can develop [sudden paralysis]. It’s a fruit salad. I think what we saw in the summer and fall of 2014, the vast majority of those children had the same thing. Whether it’s directly related to EV-D68, that’s the part we are trying to sort out.”

No Smoking Gun

Even more confounding to experts is the fact that no two cases are quite alike. Medical officials say a link between EV-D68 and AFM seems obvious, since the two upticks in cases occurred simultaneously. But while some of the paralyzed kids have tested positive for EV-D68, many haven’t. In January, the CDC reported that among 71 paralyzed patients who had their cerebrospinal fluid tested, not a single one was positive for enterovirus.

“The concurrence of EV-D68 and AFM is pretty difficult to ignore,” says Sejvar. “In the absence of any clear alternative, there is a suspicion that EV-D68 could potentially have played a role [in these cases of paralysis and limb weakness]. Unfortunately we don’t have the smoking gun that would allow us to say with absolute certainty that’s the case.”

An early attempt to establish diagnostic criteria for AFM was highly specific, with MRI images of lesions in the spinal chord being a requirement. But now experts worry that criteria set the bar higher than it should have been. “We know we are missing cases,” says Sejvar, who says MRI images can appear different based on when it’s taken. “It’s entirely consistent and possible that some children do have AFM, but for one reason or another were not meeting the CDC case definition that includes the MRI findings.”

While the CDC is still actively investigating what may have caused the recent cluster of AFM cases, it’s hit roadblocks. For instance, the agency developed an antibody test to see whether children with AFM were also more likely to have antibodies against EV-D68 compared to other healthy children. But the researchers discovered that nearly everyone in the general public has those antibodies, making the comparison useless to investigators.

Parents are looking for answers, too. A few days after Sheehan’s daughter was featured in a local news story, a woman named Erin Olivera, from Moorpark, California, sent her a friend request on Facebook. She said she’d gone through the same experience with her 3-year-old son Lucian in 2012. Though Lucian has slowly gained back some control over his legs since the initial onset, Olivera says he’s not “100%” and that she’s still looking for answers.

“I realize it’s frustrating to not have a definitive answer, particularly for parents,” says the CDC’s Sejvar. “We are working as hard as we can to establish the underlying cause.”

Parents Band Together

Together, Olivera and Sheehan created two Facebook support groups—one public, one for members—for families impacted by AFM. They launched the groups in January and now have about 90 members.

“We have a lot of polls going to see if we can figure out similarities,” says Sheehan. The patterns the women have noticed include: Most of the kids, their parents say, developed respiratory infections some time between August and December 2014, and shortly after that, their children had numbness, weakness or paralysis in one or more of their limbs. Many of the children were given steroids to treat their respiratory symptoms. Many had siblings who were also ill with a respiratory virus but had no paralysis. And many of the children have family members who have autoimmune diseases. (Some of these shared experiences are more substantiated than others.)

Some of the parents have signed up their kids for a clinical trial at Johns Hopkins that’s comparing the DNA of children with AFM who had an enterovirus infection to their siblings who also got sick but were not paralyzed. The researchers want to see if there are any genetic mutations that may make one child paralyzed and the other not.

Sheehan and Olivera plan to create a hub where science-based information about the disease can be easily shared by families facing similar situations. They hope growing awareness will encourage more attention for their children and the mysterious disorder. And just as much as the parents share research, they also share frustration. “There’s over 100 kids who are paralyzed and no one’s talking about it,’” says Megan Barr. “We are all kind of feeling around in the dark.”

Read next: Nearly Half a Million Babies Die From Poor Hygiene

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com