Here’s an SAT-level analogy question: Is Chief Justice Roy Moore of the Alabama Supreme Court to the marriage equality movement what Alabama Governor George Wallace was to the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s?

The comparison is an easy one to make, and numerous outlets drew the connection on Monday, in the aftermath of Moore’s attempt to halt same-sex marriages in his state. Facing integration of the University of Alabama in 1963, which had been mandated years earlier by Brown v. Board of Education, Wallace tried to block the change and was met by National Guard troops. This week, Moore defied a federal District Court ruling by ordering local probate judges not to license same-sex marriages, a bold challenge to the established principle of federal supremacy over state courts. In short, both Wallace and Moore relied on states’ rights claims to defy the federal government’s demand for social change.

Still, while some may see Moore’s last stand as a symbolic stand like Wallace’s, historians say the difference in context suggests that Moore is more likely to disappear with a whimper than a bang. Wallace was a martyr for a population heavily invested in the status quo. Moore is a martyr for a population resigned to change.

“Wallace was riding the segregation wave at its height,” says Dan Carter, author of George Wallace biography The Politics of Rage. “The fundamental difference is that accepting gays and lesbians and their rights is not nearly as painful. I think the gay issue, even in the deep South, in the most conservative areas, it’s kind of a resigned acceptance.”

An analysis of demographic and voting data by the New York Times suggests that two-thirds of state residents are likely opposed to the unions. But opposition today is not nearly as strong as white southerners’ opposition to civil rights for black Americans was in 1963, Carter says, pointing to Southern newspaper coverage. In the 1960s, few Alabama newspapers would dare publish anything sympathetic to civil rights, according to Carter. On Monday, when same-sex marriages began, the state’s largest newspaper said it was an “extraordinary day.”

And, though a conflict between the state and federal governments persists — probate judges in some Alabama counties aren’t issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, citing Moore’s guidance — it remains unclear how the federal government will respond. At this point, it seems unlikely that such a response would mirror what happened in the 1960s.

“Bobby Kennedy was willing to bring in federal marshals, willing to nationalize the National Guard in states,” says University of Alabama history professor Glenn Feldman, referring to the then-Attorney General’s response to Wallace in the 1960s. “I’m not sure if the federal government today has the political backbone or will to make people respect it.”

Whether or not the White House ultimately cracks down on wayward Alabama judges, it’s hard to imagine that the situation would escalate as it did in 1963, when President John F. Kennedy sent in the National Guard to force integration. That’s because, in all likelihood, such measures would probably be unnecessary. Some of the judges under Moore’s purview ignored his order, and others said they’re waiting for clarification. Furthermore, Moore only has authority over the state’s judicial employees, not the state troopers and others whom Wallace used to fight integration.

Today, conservative Alabama Governor Robert Bentley seems sympathetic to Moore and hasn’t tried to restrict him. (He’s said he doesn’t want to “further complicate this issue.”) But he also seems likely to comply with the Supreme Court’s ruling. “The issue of same sex marriage will be finally decided by the U.S. Supreme Court later this year,” he said in a statement. “I have great respect for the legal process, and the protections that the law provides for our people.”

For his part, President Obama — who has addressed the comparison to Wallace — also seems to believe that the courts can take care of this issue on their own, without the kind of intervention that was necessitated five decades ago. “I think that the courts at the federal level will have something to say to him,” he told BuzzFeed News about Roy Moore this week.

So, the states’-rights justifications for Wallace and Moore may be the same, but historical distinctions mean the resolution to Moore’s defiance is likely to be far less dramatic than Wallace’s was.

There is one more difference between them, however, and it suggests that such a resolution may not be the end of Moore’s story: Moore may not be ready to give up, even when moving on makes political sense. Wallace’s opposition to integration was driven by a political desire to win over his constituents, Feldman and Carter note, so he changed his views when it was no longer advantageous for him to oppose civil rights. Looking at Moore, however, they see someone whose deeply-held religious beliefs may lead him to push his authority further, even as the opinions of those around him evolve.

“He actually believes this stuff,” says Feldman. “He actually believes in his heart of hearts that the federal government is not a position to tell states what to do.”

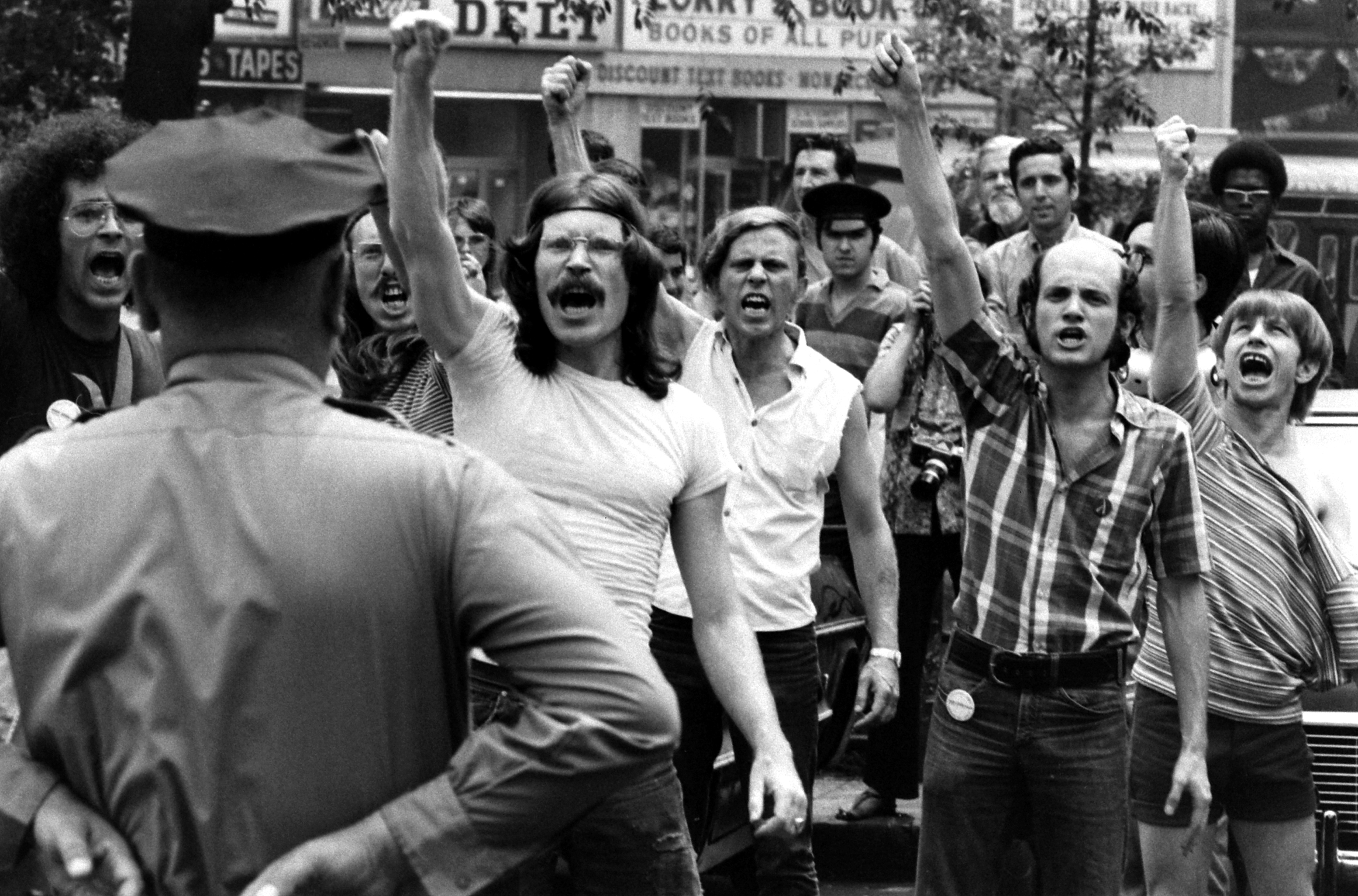

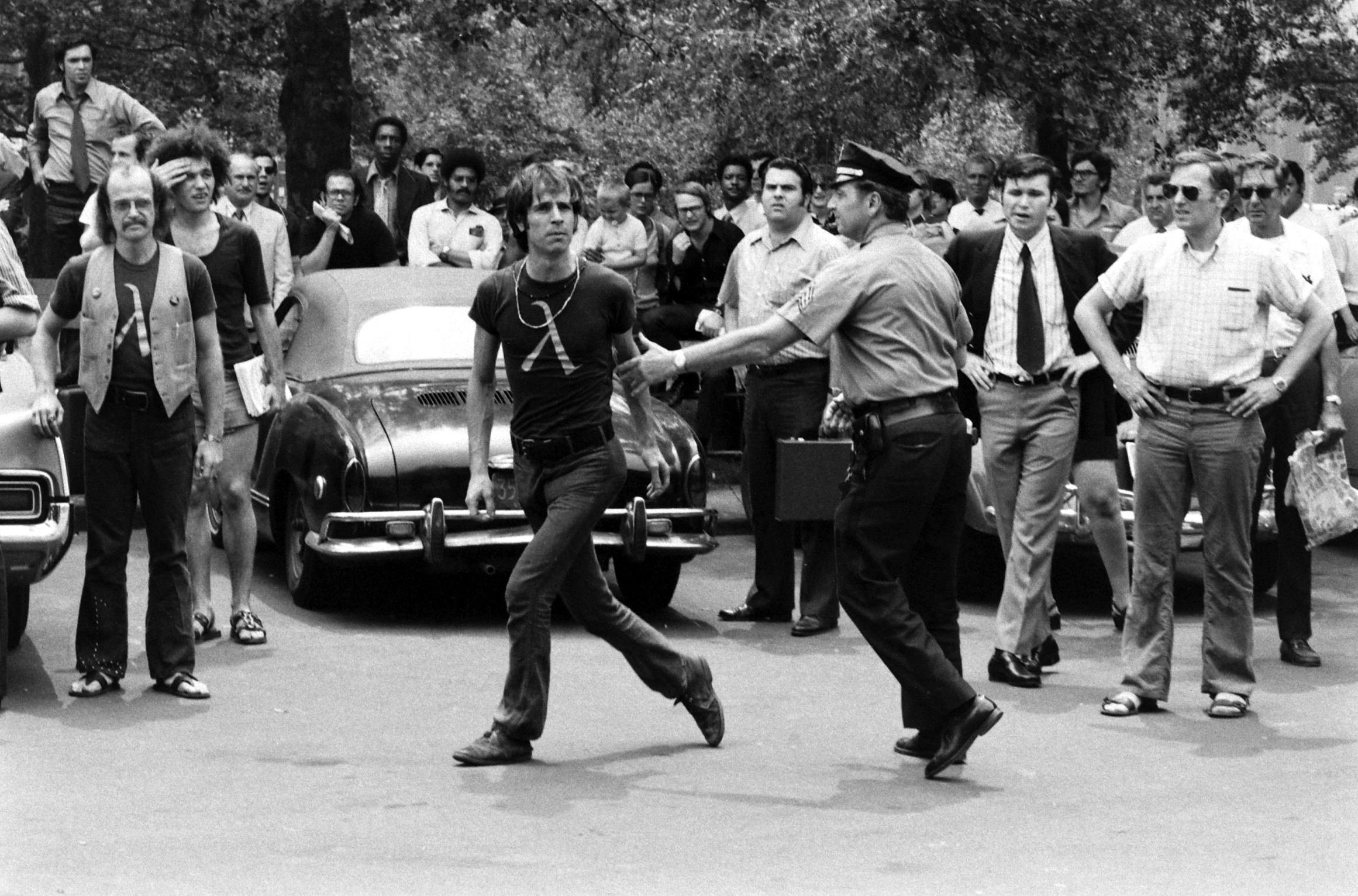

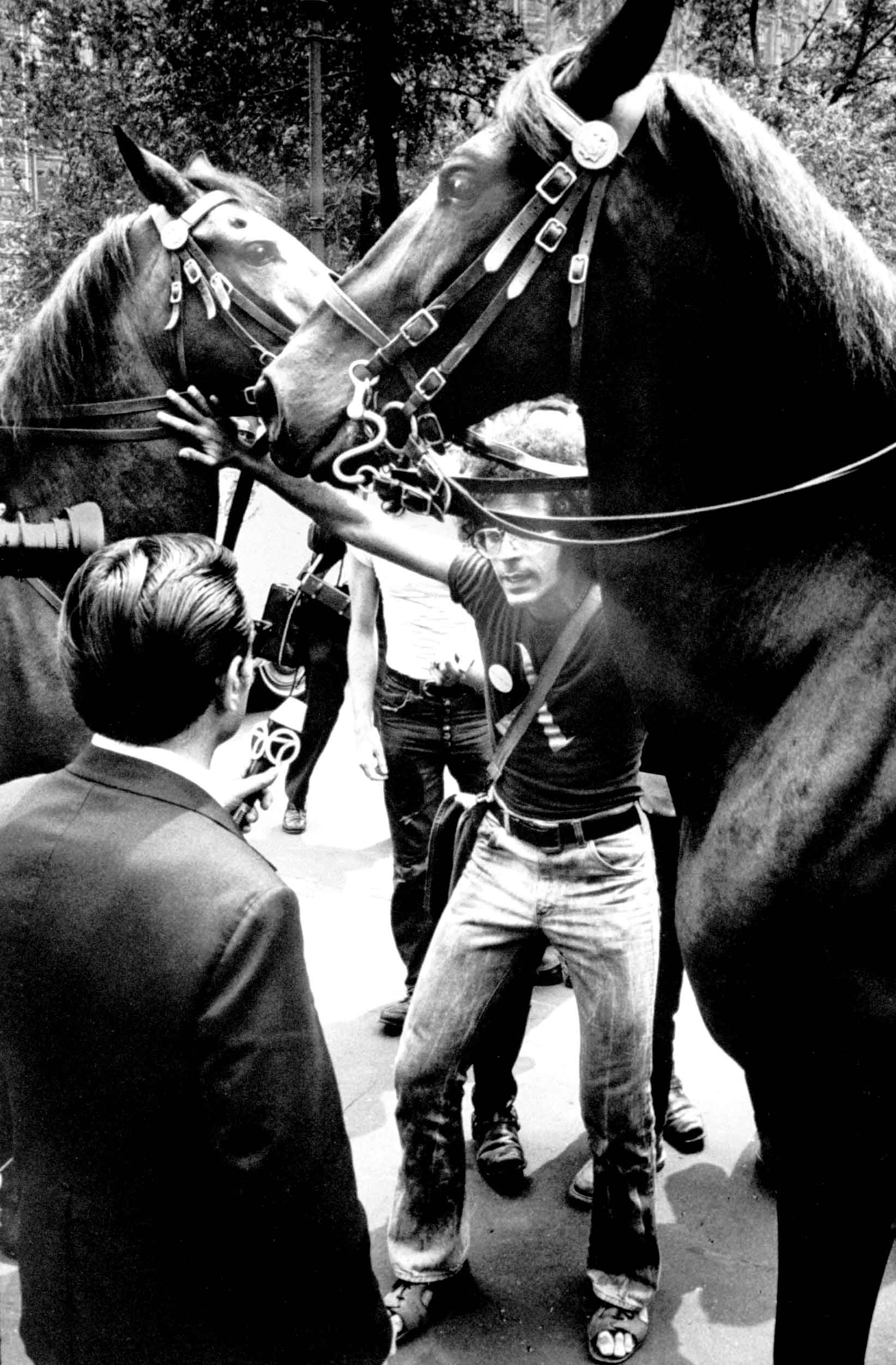

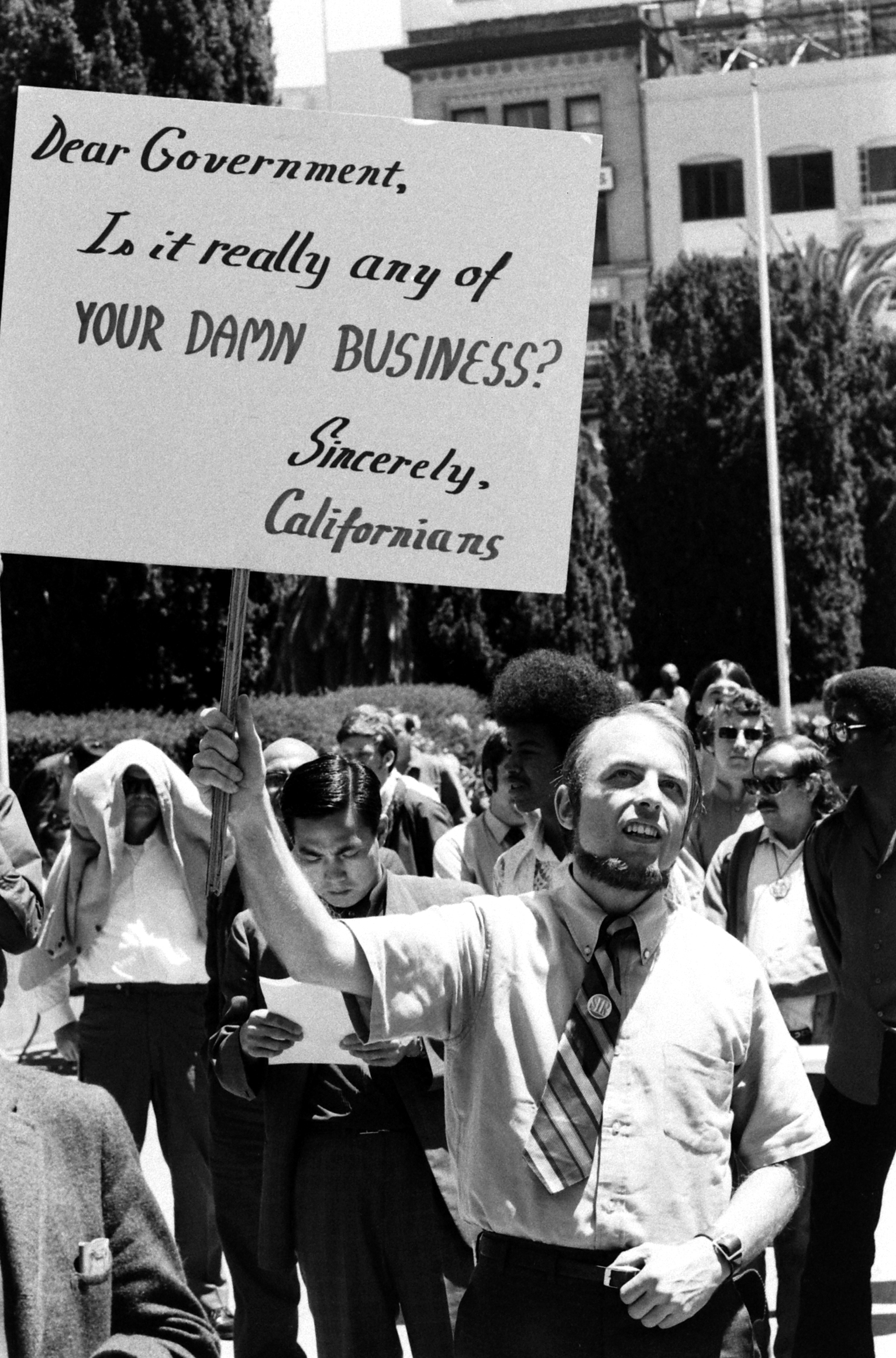

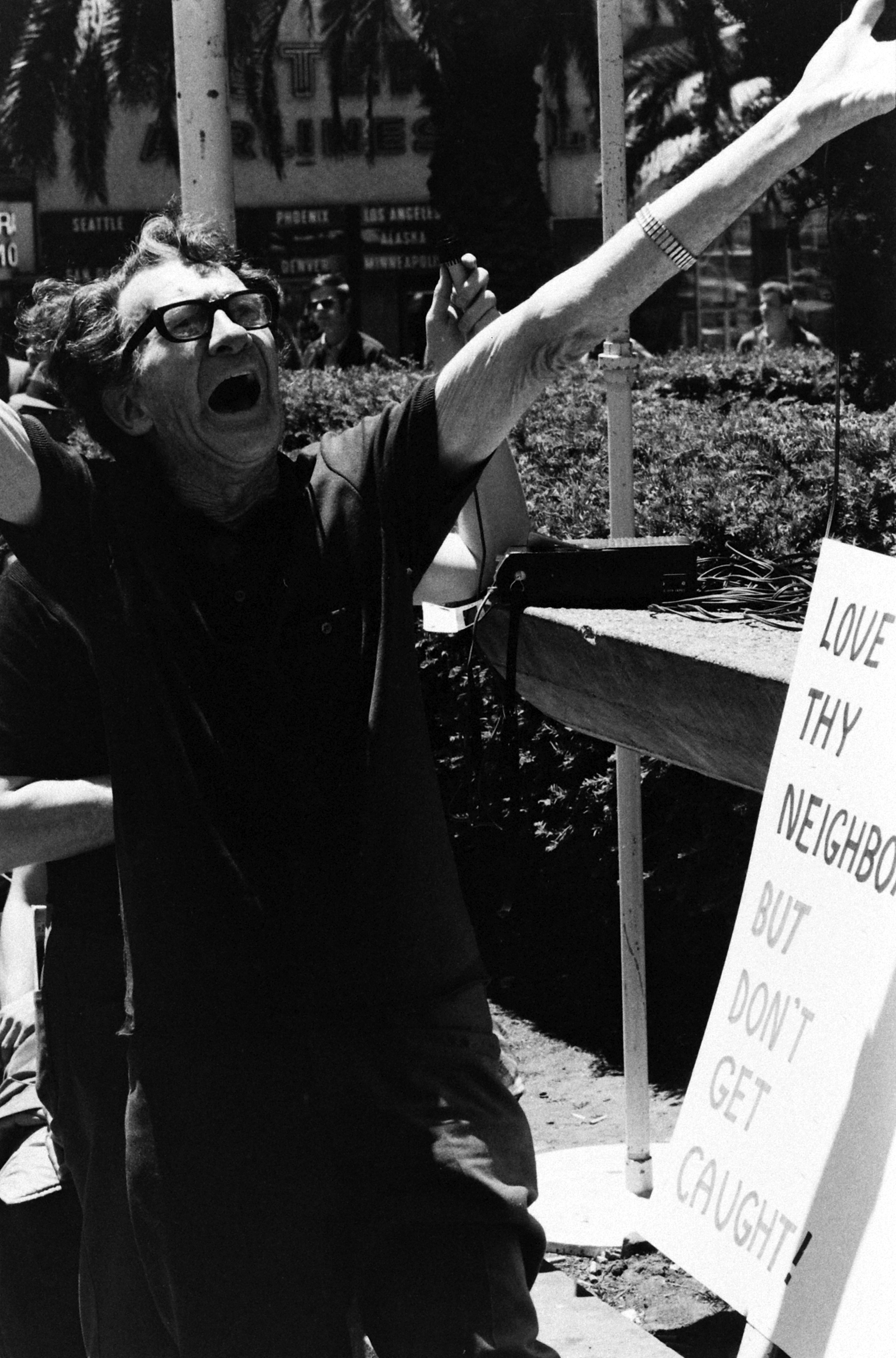

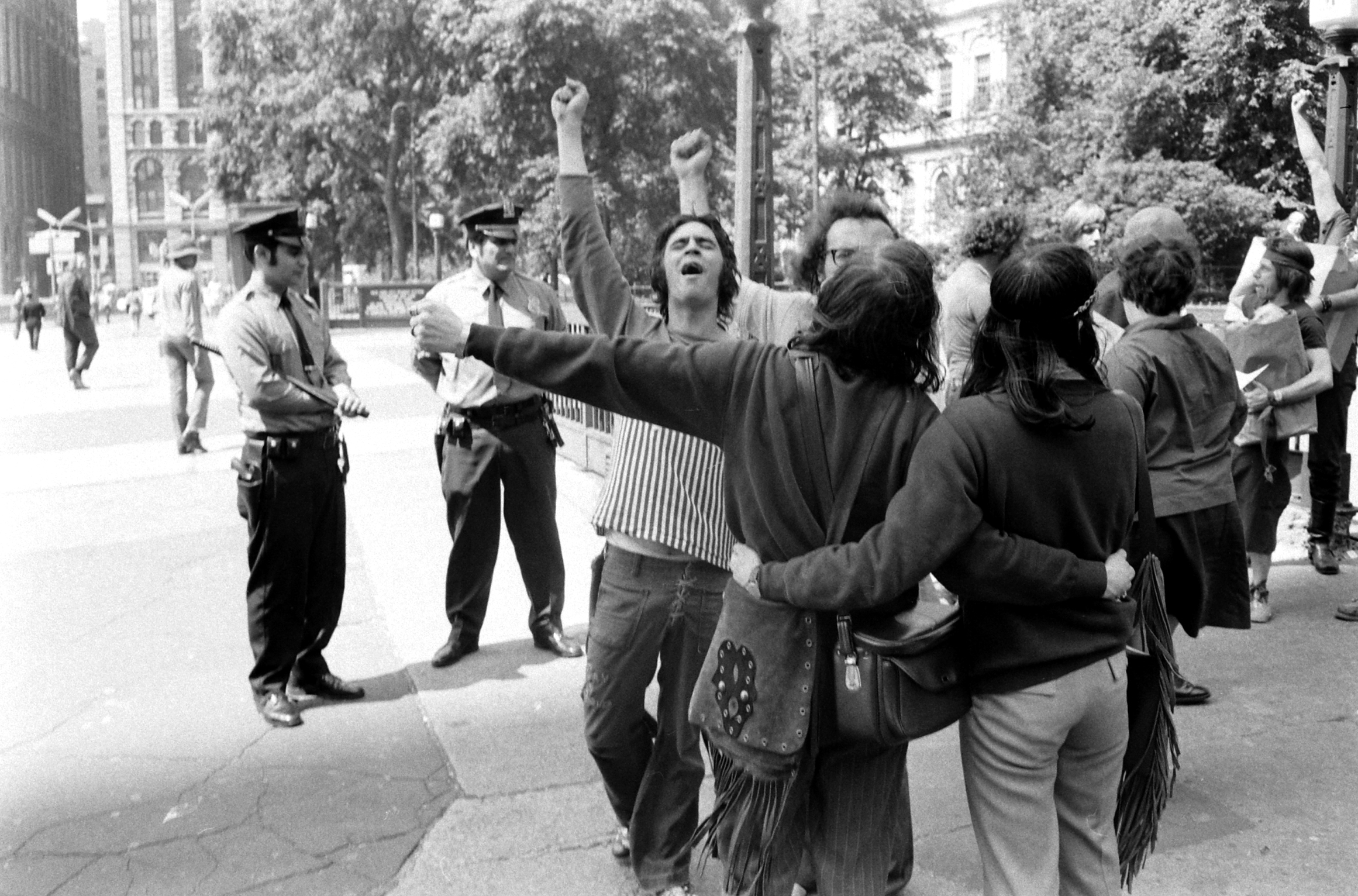

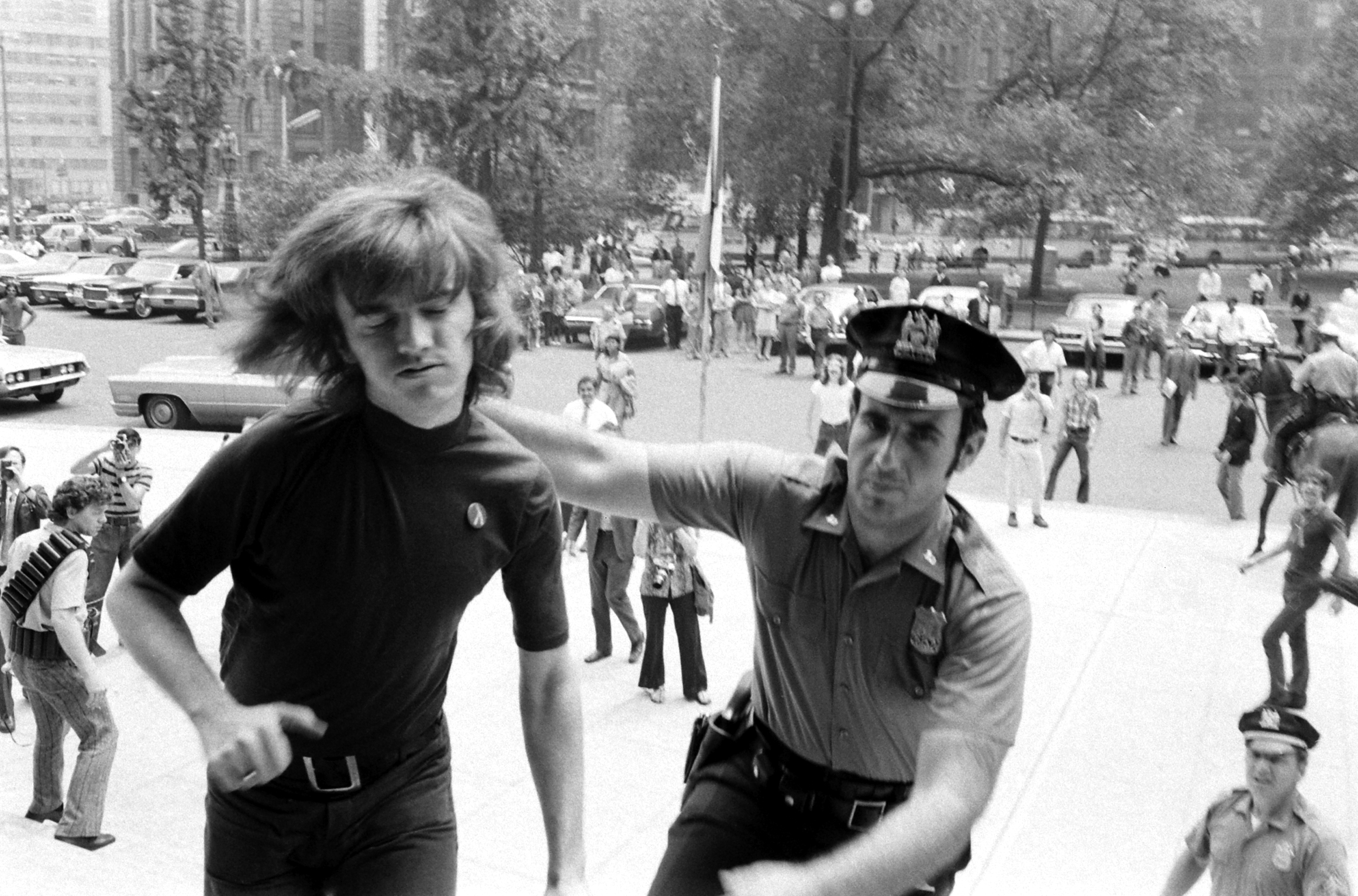

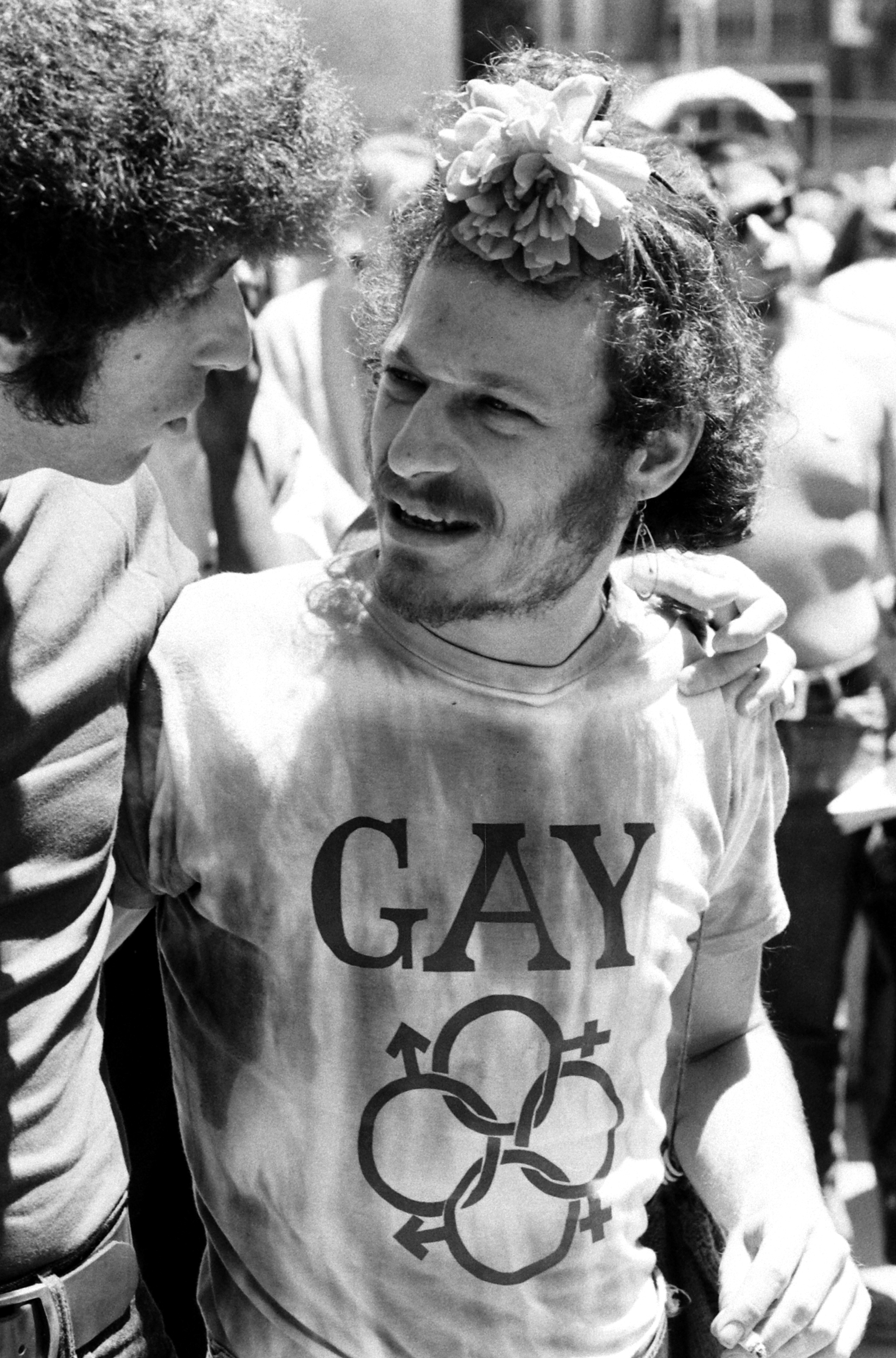

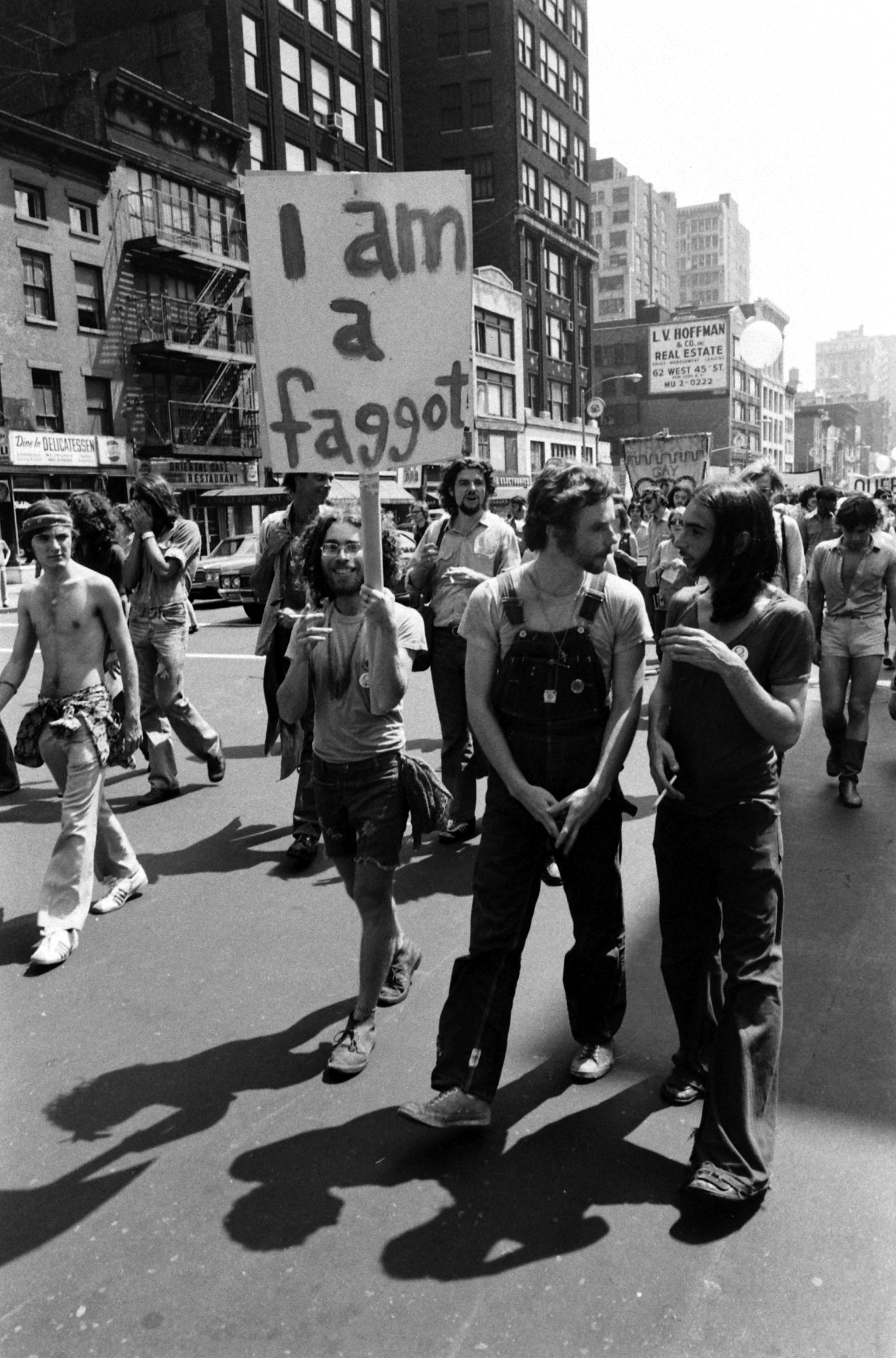

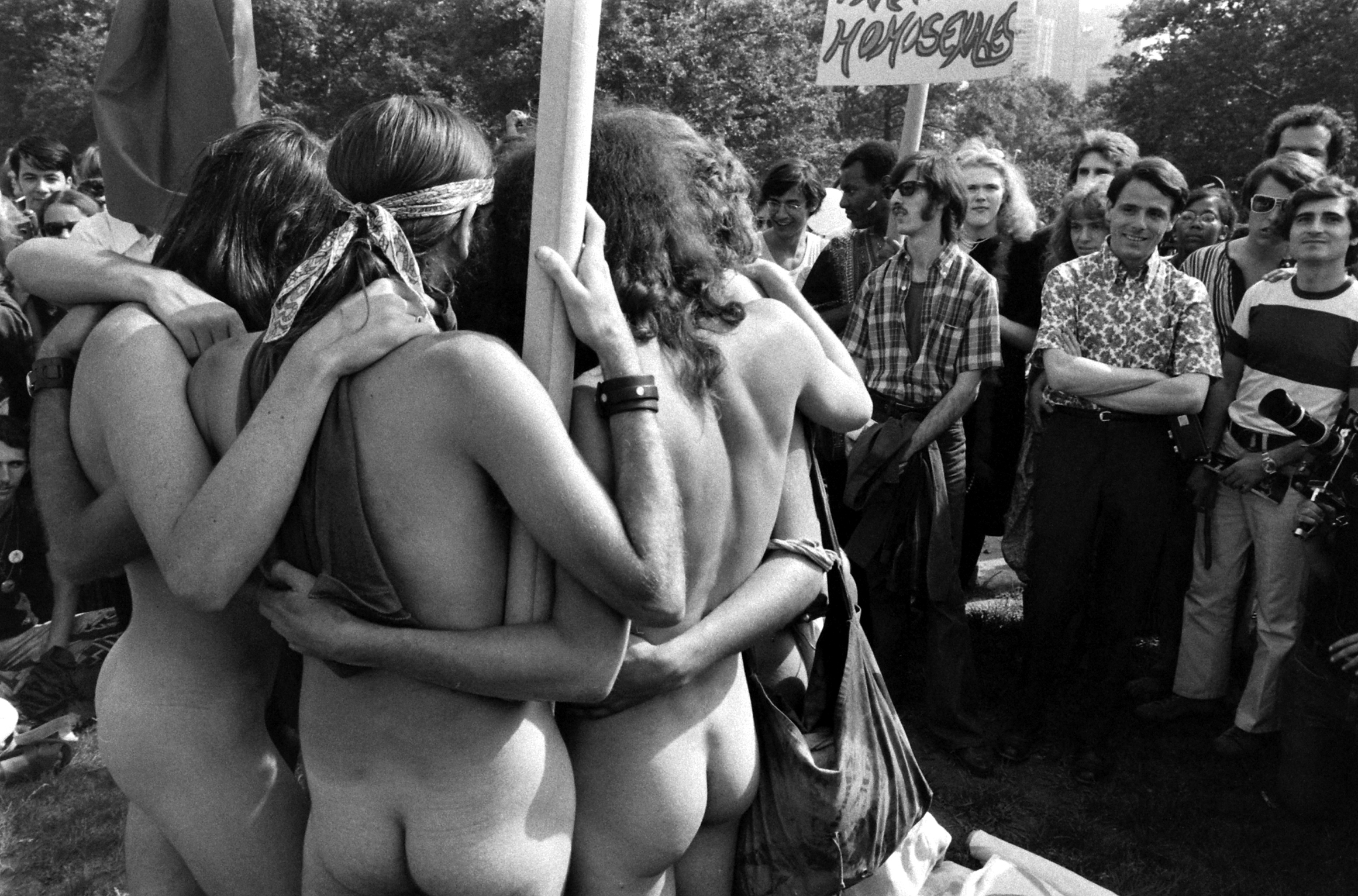

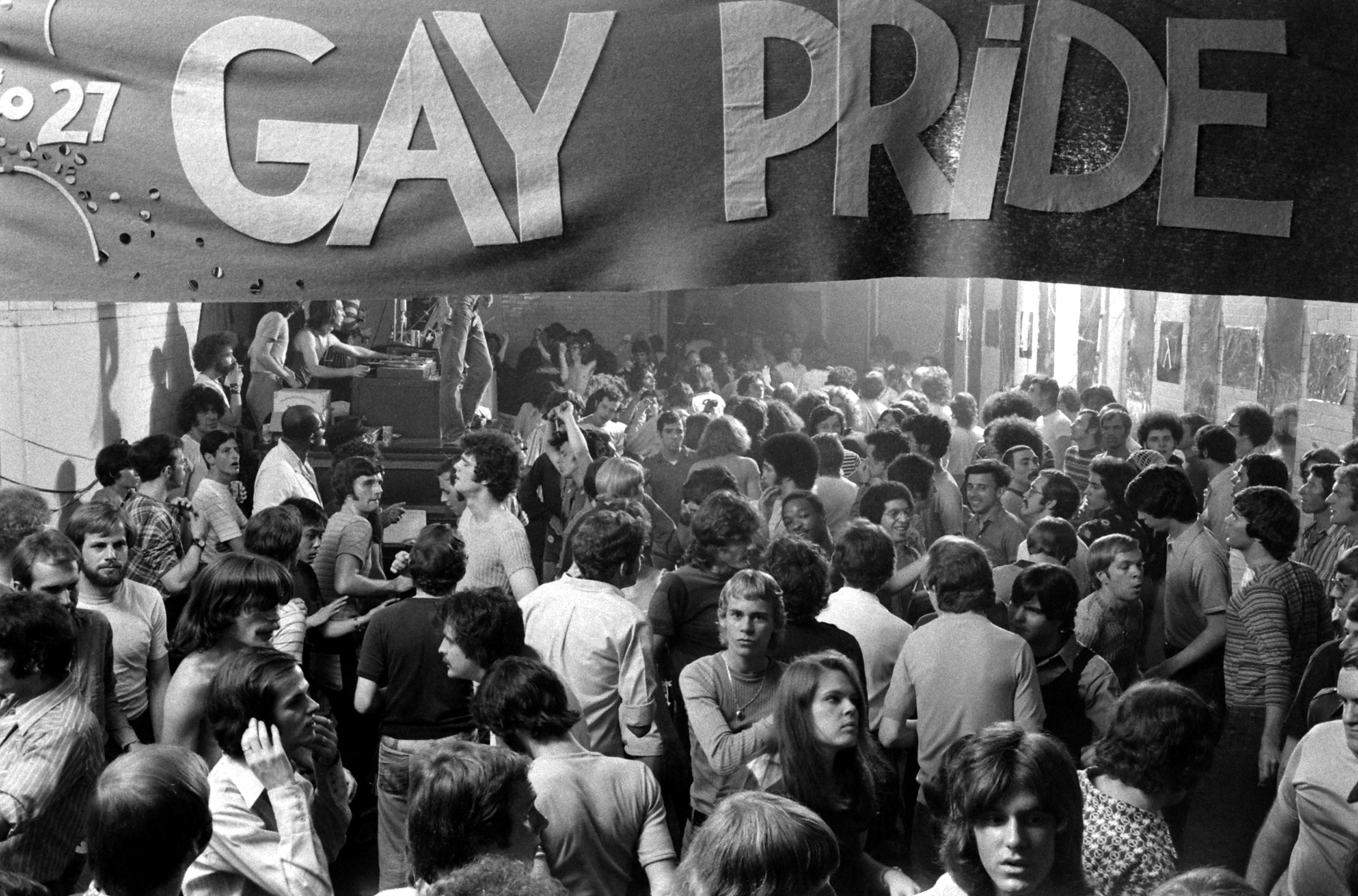

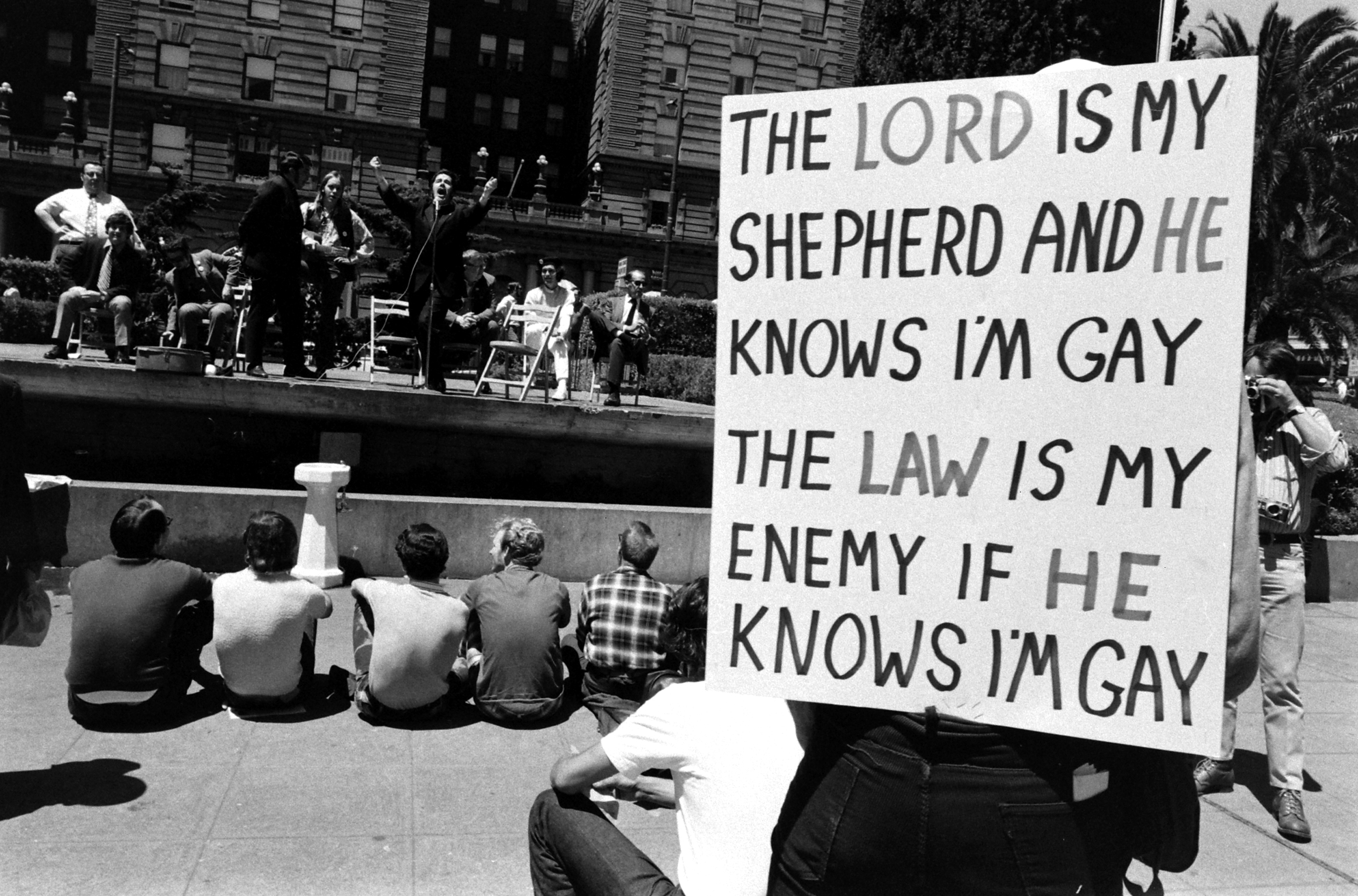

Silent No More: Early Days in the Fight for Gay Rights

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com