Violent psychopaths seem to have abnormalities in the parts of the brain that learn from punishment, according to a new study published in the journal Lancet Psychiatry. Knowledge about these brain differences could one day be used to help children whose brain makeup puts them at risk for psychopathy.

Using fMRI imaging, a team of researchers looked at the brain signaling of 50 men: 12 violent offenders—all people with antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy who had been convicted of murder, rape, attempted murder or grievous bodily harm—20 violent offenders with antisocial personality disorder but not psychopathy, and 18 non-offenders.

While their brains were being scanned, the men completed an image matching test that measured their ability to change their behavior and choices based on feedback they were getting from the game. The psychopathic men had a much harder time with changing their behavior, and they took significantly longer to adapt when the game changed its rules.

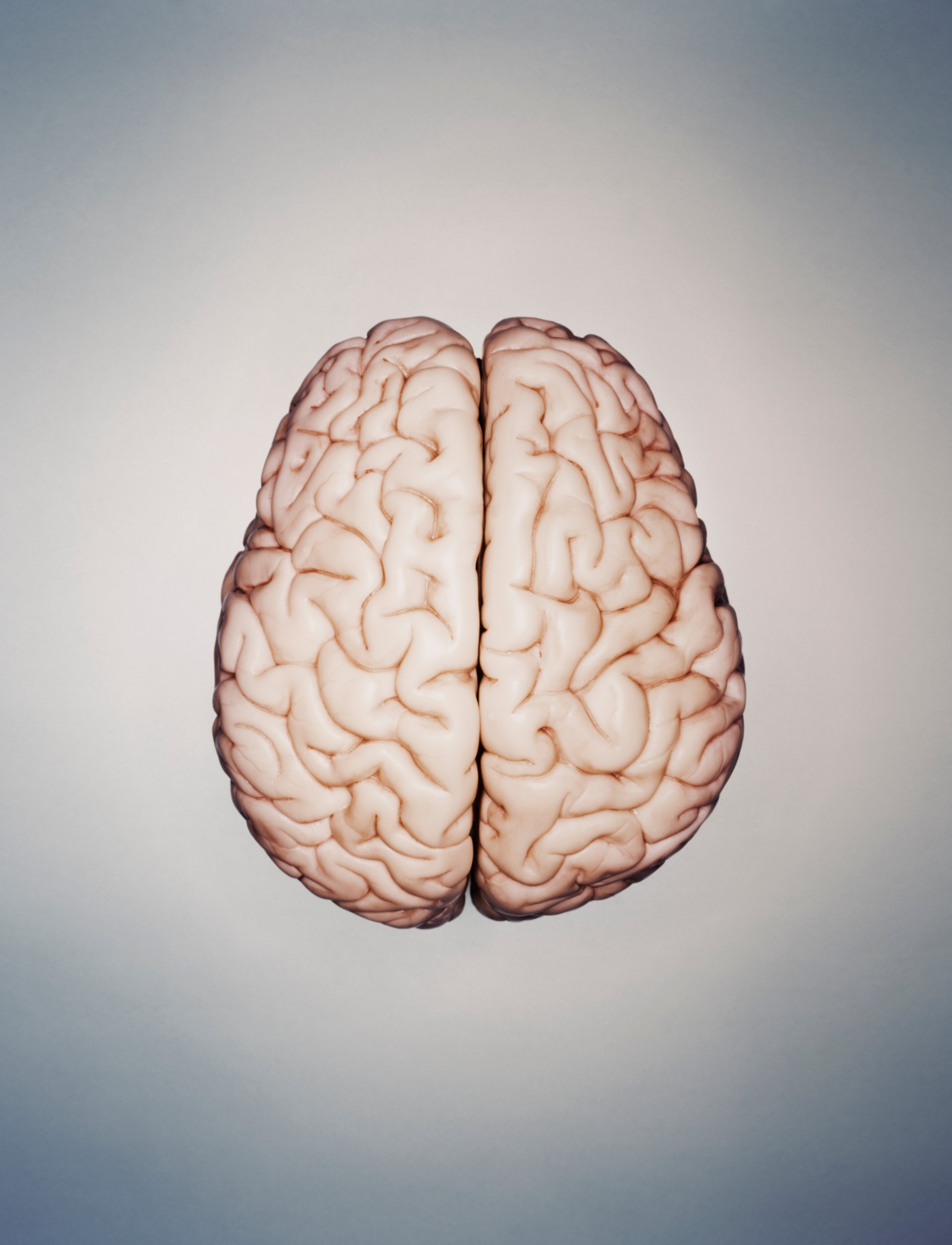

Scans of the psychopaths’ brains looked different from both non-psychopathic criminals and non-offenders, showing noticeable abnormalities in their white and gray matter—both of which are involved with connecting brain regions. The abnormalities were observed in areas of the brain where emotions like guilt, embarrassment and moral reasoning are processed. Some of those abnormalities were linked to a lack of empathy.

Prior studies of psychopaths have shown that rehabilitation efforts often fall short, which is why the researchers looked into the underlying mechanisms.

The authors write that many of the characteristics of psychopathy appear very early in age, and if caught early enough, interventions could alter brain structure. The researchers hope their findings could lead to the development of programs for parents who observe callousness and repeated violent behavior among their children early on.

“As most violent crimes are committed by men with this early-onset stable pattern of antisocial and aggressive behavior, interventions that target the specific underlying brain mechanisms and effect change in the behavior have the potential to significantly reduce the rate of violent crime,” the authors write.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com