The massacre of Charlie Hebdo journalists and cartoonists in Paris is an assault on free speech everywhere. But the same media that so fervently defends free speech in the aftermath of this tragedy makes a habit of policing language, seizing upon offensive remarks of the famous, or not so famous, and using them to manufacture outrage in pursuit of an audience.

Clearly a slaughter of 12 innocent people is countless orders of magnitude more devastating than Internet umbrage. But the motive comes from the same place: the notion that people should be “punished” for making insensitive comments or jokes, that they should pay for their words with their reputations or their jobs. In other words: You said something that offends me, so I will destroy you.

That destruction can take many forms. It could be leaking your emails and destroying your computer systems, as happened to Sony. It could be getting someone fired. It could be destroying someone’s reputation through relentless public Twitter flogging. But we forget that Internet outrage can have real-life victims (and I admit, as a writer, I’ve occasionally forgotten that). We give ourselves license to indulge in these perverse impulses out of a sense of righteousness — Down with sexism! Conquer racism! But destroying lives over objectionable language is just a different form of extremism.

Take, for example, Slate’s excellent report on the collected indignation of 2014, called The Year in Outrage. In an essay titled “How Outrage Changed My Life,” former New York Times Magazine columnist Andrew Goldman describes a series of events that led him to craft a sexist tweet about author Jennifer Weiner that ultimately cost him his job and livelihood. Afterward, he wrote, “I was surprised when she expressed that she felt that she and I had been equivalently wounded by what happened, that having had my reputation and career permanently marred was comparable to being insulted on Twitter.”

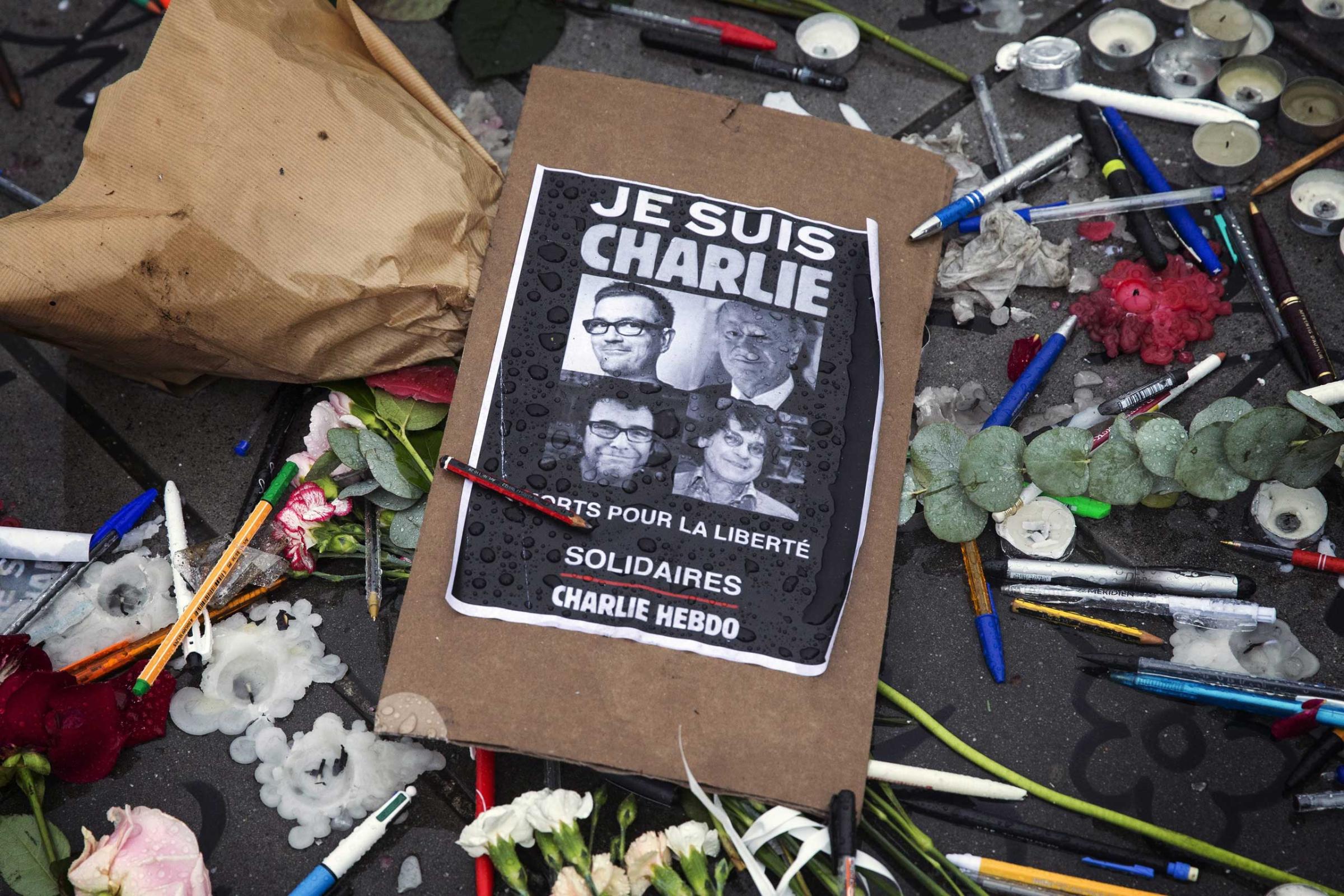

See Photos of France’s National Day of Mourning:

France Stands in Silence for Terror Attack Victims

Or look at Justine Sacco, the PR executive whose tone-deaf tweet about AIDS in Africa cost her her name and her career. After Sacco tweeted a racist joke and got on an airplane, the world (and the media) waited for her to land, at which point she “emerged into an unfathomable modern multimedia hell-nightmare and was quickly and summarily fired,” wrote Sam Biddle at Gawker, who was early to the Sacco pile-on and has since come to regret it:

“Twitter disasters are the quickest source of outrage, and outrage is traffic. I didn’t think about whether or not I might be ruining Sacco’s life…Each time, each slap, was the same: If we could only put one more wrongheaded head on a pike, humiliate one more bigoted sorority girl or ignorant Floridian, we could heal this world. Each, next outrage post was the one that would make a difference.”

The notion that somebody deserves to have their life and career ruined for tweeting an offensive comment or bad joke is an out-of-proportion response, driven by righteous indignation. The answer to a tasteless comment or cartoon is discourse, not destruction, but too often, we sanction professional immolation as a fitting consequence of objectionable speech. It’s a snowball effect, because nobody wants to defend someone who is being accused of bigotry, lest they be labeled a bigot themselves. There’s even a whole Tumblr devoted to policing social media and reporting racist comments to employers, called “Racists Getting Fired.” And as anyone who’s ever been the object of online vitriol knows, public finger-pointing is usually enough to make you rethink your assumptions and prejudices. You don’t have to lose your job over it.

Goldman was mocking women, Sacco was mocking AIDS (or so we thought at the time), Sony’s film was mocking Kim Jung Un, Charlie Hebdo was mocking Muhammad — which of these you find most offensive depends on who you are. If we defend one of them as free speech, we must defend them all.

If all of us standing up for Charlie Hebdo are truly committed to the freedom of speech — and we all should be — we need to stop demanding professional punishment whenever somebody says something idiotically sexist, racist or classist. Embarrassing comments, in most cases, should not cost people their jobs or livelihoods. We should disagree with people, but not aim to destroy their lives.

“We can’t live in a country without freedom of speech,” Charlie Hebdo’s top editor Stéphane Charbonnier once said in an interview. “I prefer to die than to live like a rat.” But in a media climate that is largely fueled by outrage and retribution, we are all living like mice.

Read next: Blasphemy Is at the Front Lines of Free Speech Today

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com