The Supreme Court on Monday will consider whether violent language posted on social media is covered by the First Amendment’s protection of free speech.

The case, Elonis v. United States, hinges around the question of whether a Facebook message can be considered a “true threat,” or a threat a reasonable person would determine to be real. That would be an important distinction, because “true threats” don’t get First Amendment coverage. But it won’t be an easy problem to solve: While it can be easy to call a threat “true” if it’s given verbally, making that call gets harder when threats are posted online, where they lack the context, tone and other indicators of intent present in verbal communication. It’s also arguably easier to make threats online, especially if it’s done anonymously.

What happened?

A lower court had sentenced Pennsylvania man Anthony Elonis to about four years in federal prison over several Facebook posts threatening his estranged wife. The posts included, among other things, raps about slitting his wife’s throat and about how her protection order against him wouldn’t be enough to stop a bullet.

A sample:

There’s one way to love you but a thousand ways to kill you. I’m not going to rest until your body is a mess, soaked in blood and dying from all the little cuts.

But how is that not a “true threat?”

Elonis contends his posts weren’t a threat to his wife but rather a therapeutic form of expression. It’s commonly accepted that violent images are often part of rap music and other media, and artistic expression is protected under the First Amendment, explaining Elonis’ legal strategy. Still, the issue of whether Elonis had the intent to threaten is not necessary for a threat to be deemed a “true threat.” That requires only for a reasonable person to believe a threat is authentic.

“The dividing line here is whether we’re judging the threat based on the intent of the speaker, or on the reaction of the people who read it and would’ve felt threatened. That’s really the key question,” said William McGeveran, a law professor at the University of Minnesota.

What if the court upholds Elonis’ conviction?

Several experts agree that such a decision could stifle freedom of speech online and offline, particularly among artists. If the court rules against Elonis, artists could be more hesitant to share anything that could be perceived as threatening — a slippery slope. On the other hand, such a ruling could increase the number of online harassment cases aggressively pursued by law enforcement. And there could also be a censorship effect on social media companies like Facebook.

“You have the potential for creating a chilling effect both on the part of speakers, but possibly even more on the part of entities that host potentially threatening speech,” said Paul Levy, an attorney at the Public Citizen Litigation Group. “If intent [to threat] isn’t needed [to prosecute], then it seems that the Facebooks of the world have to worry that they, too, can be prosecuted. It could have a serious censoring effect.”

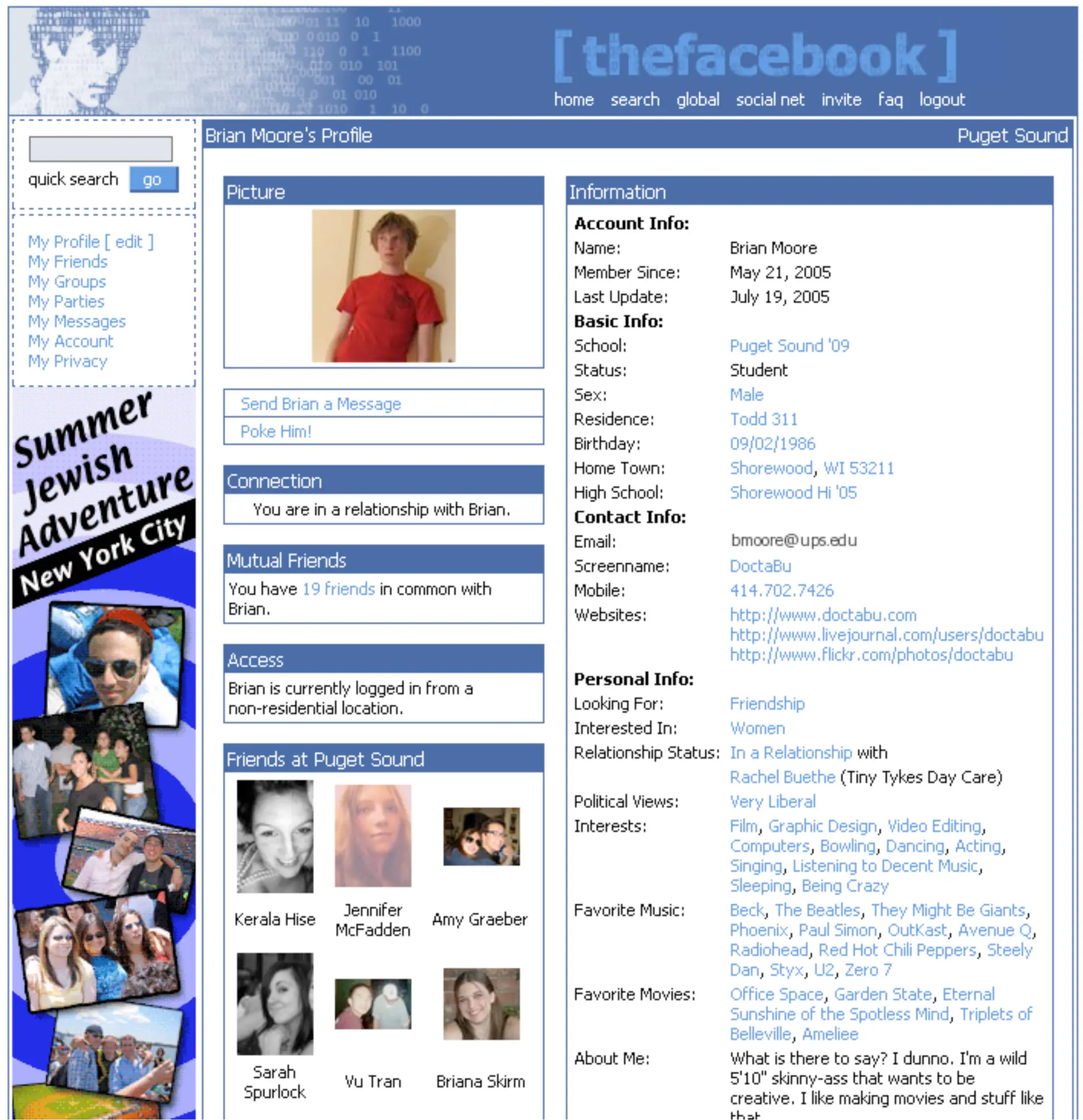

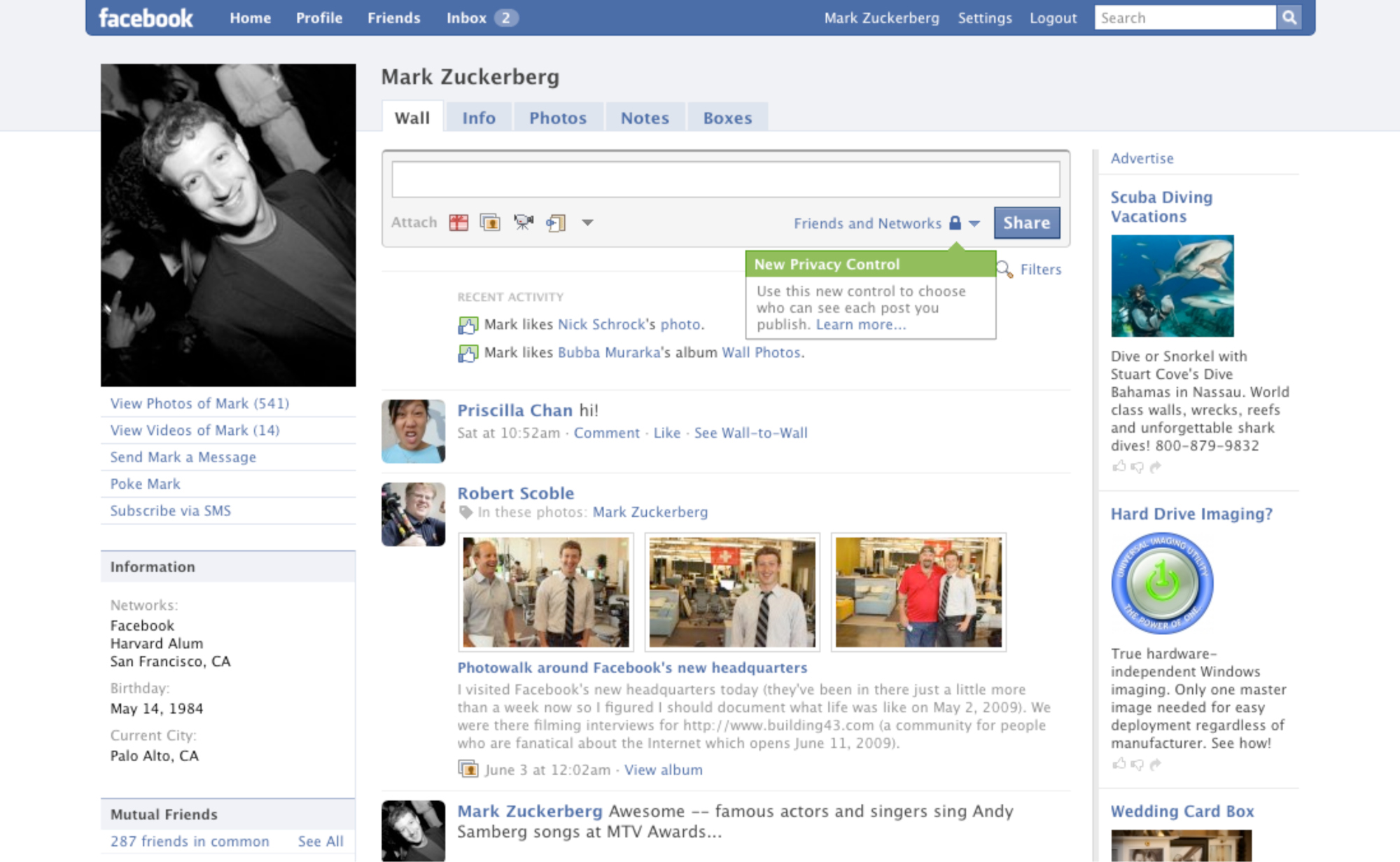

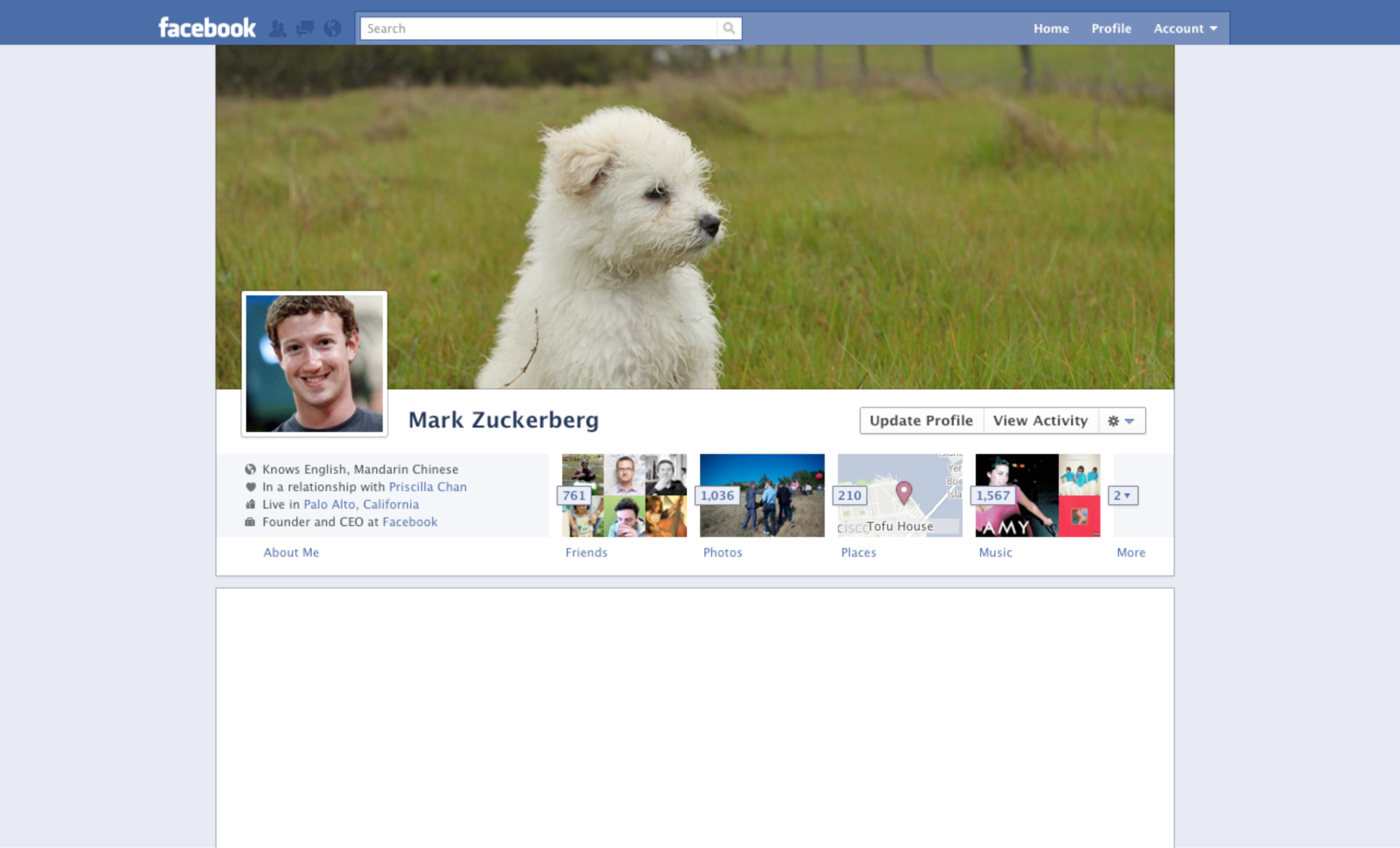

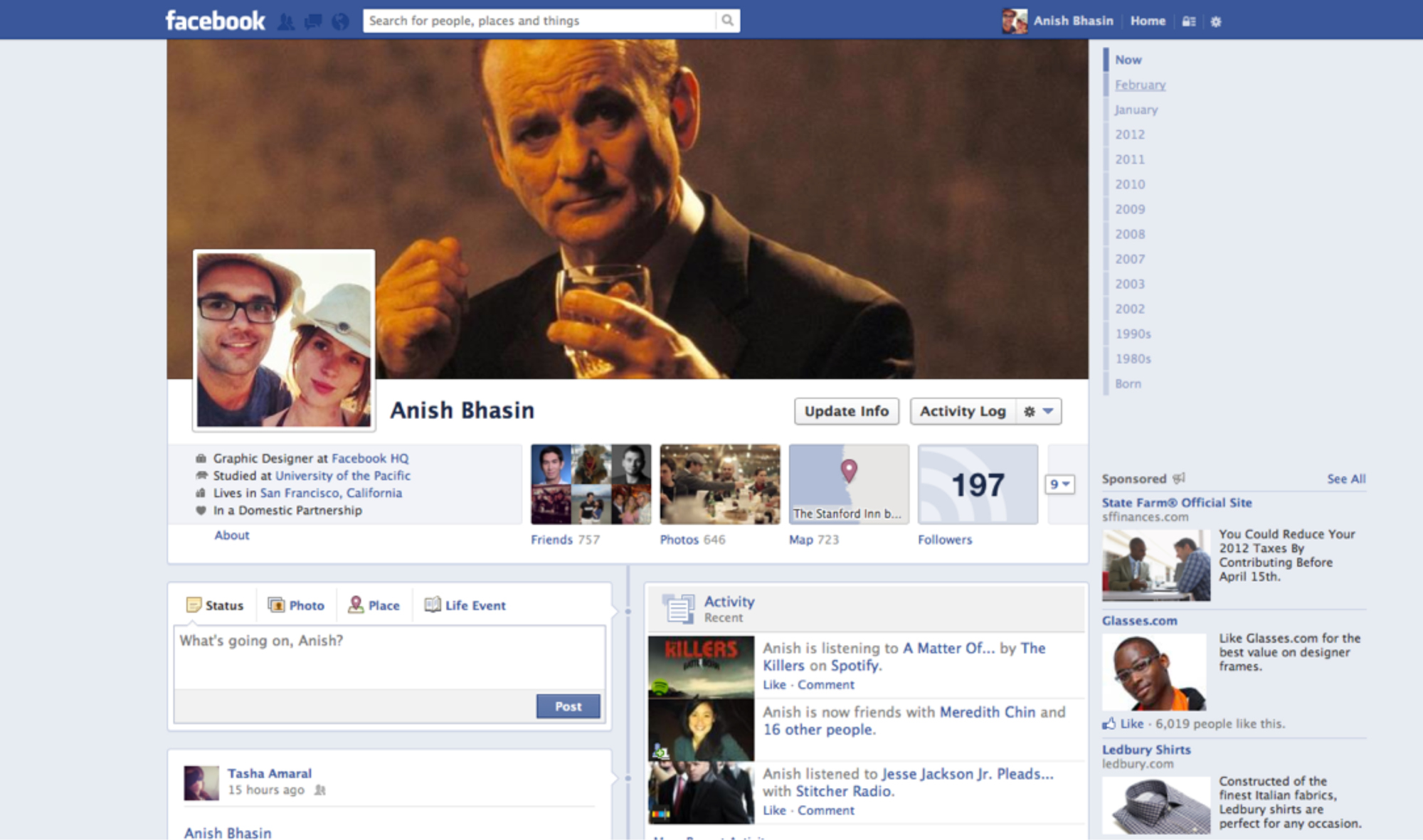

This Is What Your Facebook Profile Looked Like Over the Last 11 Years

What if the court rules in Elonis’ favor?

Some experts agree this is probably what the Court will do. In the past, the Supreme Court has demonstrated a commitment to protecting all kinds of speech, however vile or unpopular, by citing the First Amendment to protect everything from a filmmaker’s “animal crush” abuse videos to the Westboro Baptist Church’s anti-gay public speech.

“The First Amendment is one of the strongest protections of free speech in the whole world, and it’s a very rare thing to have a law that actually makes it a crime to express certain ideas,” said Marcia Hoffman, an attorney and special counsel to digital rights group Electronic Frontier Foundation.

But if the Court chooses to overturn Elonis’ conviction, that move might not provide a clearer definition of which online threats constitute a “real threat.” That would leave us legally in the dark when it comes to abuse over the Internet.

“Society is still struggling to really figure out how the Internet works and how it affects people, both users of the Internet and subjects of the speech on the Internet,” said William Marcell, a law professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “I think the court might want to buy a little bit more time to see if a threat over the Internet is really as serious as one face-to-face.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com