The so-called “black box” is the most severe warning label issued by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and for the past decade, antidepressants have been among the drugs that bear them. That means the pills come with a notice cautioning users that the drugs may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in children and young adults. But now, many experts say it’s time for the black box to go: that the warnings overstate the real risk and may deter doctors from prescribing them to people who could benefit from being on antidepressants. Depression, after all, is the biggest risk factor for suicide.

“There’s absolutely no evidence that [the boxed warning] has done any good. There’s certainly credible data that it’s done harm,” says Dr. Richard Friedman, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College who recently wrote an op-ed calling for the removal of the black box in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). Dr. Marc Stone of the FDA, meanwhile, wrote a companion critique in NEJM, and tells TIME the data suggesting the black box should be removed is “extremely questionable; virtually meaningless.” Evidently, even experts disagree.

TIME spoke to 17 leaders in the field of psychiatry to get their take on the black box warning on antidepressants: 11 said the warnings should be removed; two think the media has overblown the suicide risk posed by antidepressants, resulting in more panic than is necessary; and four support the box’s place on Rx drugs. Among those four, three were involved in the FDA’s decision to issue the black-box warning 10 years ago.

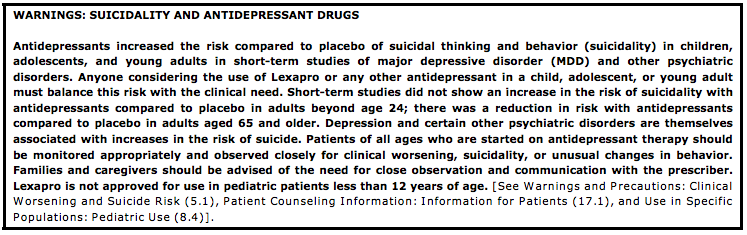

Back in 2004, the FDA was prompted to look into the effects of antidepressants after data emerged linking the drug Paxil to suicidal thoughts. An FDA committee then analyzed existing data about suicidal thoughts in people on antidepressants. There were no actual suicides among children in the clinical trials, but there was a slight increase in what is called “suicidality”—suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The rate of suicidality was 4% among patients taking an antidepressant compared to 2% taking a placebo. Ultimately, the committee deemed it enough of a risk to tack on the boxed warning.

“I recognized there could be a chilling effect on prescribing, but I thought it was important to get the message [about possible side effects] out. At least that’s certainly what I felt at the time,” says Dr. Wayne Goodman, chair of psychiatry at Mount Sinai Hospital, who led the FDA committees back in 2004.

Studies have shown that antidepressant use and prescriptions did drop after the warnings were added. In June 2014, Harvard researchers published a study in the BMJ linking awareness of the warning to a decrease in antidepressant use and simultaneous increase in suicide attempts among young people. All the data, however, is observational. Data does show that from 2000 to 2009, suicides have gradually increased.

But back in the early 2000s, says Goodman, the FDA’s hands were tied. Worry about antidepressants and suicide became hugely politicized. Goodman, who says he’s open to revisiting the issue, still vividly remembers family members’ graphic testimonies. “[My mother] completely transformed into an emaciated woman who paced the floors, picked her skin, barely slept, and struggled to perform the simplest tasks like cooking a meal,” reads the transcript of one woman’s testimony of how her mother hung herself after just 10 weeks on antidepressants. The committee heard nearly 80 similar claims.

The FDA’s intention at the time was to quell public fear and to ensure that doctors and patients to have a discussion about risks, and make sure physicians monitored their patients during vulnerable periods, particularly during the first few months when some people get worse before they get better. “The intention was never to discourage appropriate use,” says Dr. Thomas Laughren, former director of the FDA’s Division of Psychiatry Products, who remembers being booed and hissed at professional meetings after the decision.

Still, not every expert agrees the pills are a panacea. “I’m 70 years old, I’ve been practicing for a long time,” says Dr. Norman Sussman, a psychiatry professor and clinician at New York University. “I’m not enamored by these drugs. They have their limitations and they really don’t work for most people, but the ones they work for best are the ones who are the most seriously depressed.” While the drugs may not be for everyone, most of the experts TIME spoke with agreed that the warnings deter depressed people from taking drugs that could improve their wellbeing.

“We don’t want wild and crazy prescribing, but we don’t want good clinicians afraid to use useful drugs,” says Dr. Mark Riddle, Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics and Johns Hopkins. “Though I am generally a cautious person and most of my research is on side effects, I think the FDA needs to back off a little.” The FDA does not currently have plans to revisit the warning.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com