Even the most devout Wonder Woman fanatics probably didn’t know that the heroine’s creator, William Moulton Marston, a psychologist, lived with and had children with two women at the same time. They also probably didn’t know that he had slightly strange theories about the benefits of bondage. Nor is it common knowledge that the character, which debuted in 1942, was inspired by the leaders of the suffragist movement.

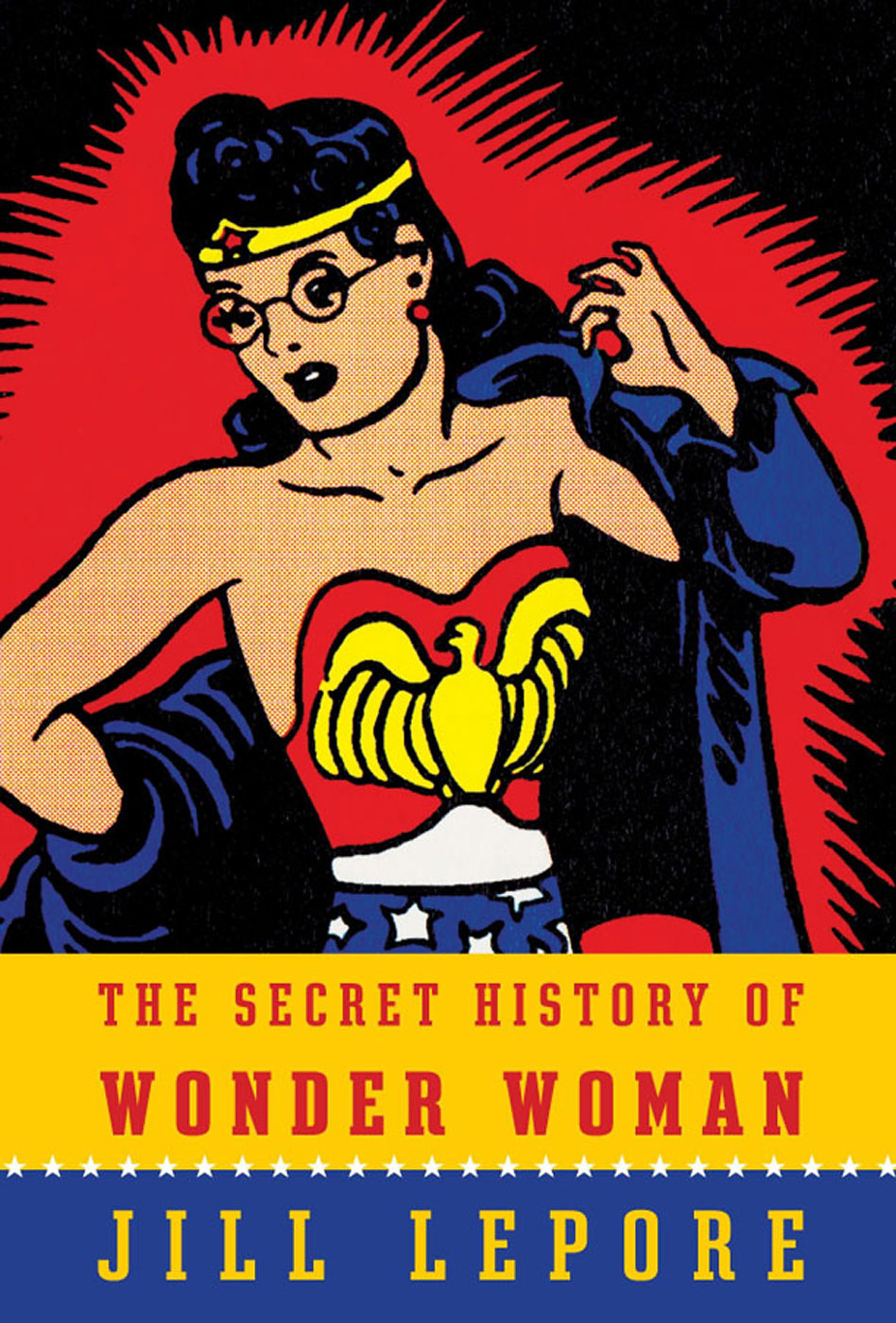

In her new book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, which hits shelves Tuesday, New Yorker writer and Harvard professor Jill Lepore delves into the life of the man who created Wonder Woman. The book comes just as Wonder Woman is swooping back into the cultural consciousness with her invisible jet. Israeli actress Gal Gadot will play Wonder Woman in 2016’s Batman vs. Superman and will get her own solo film in 2017.

Here’s just some of what Lepore uncovered:

1. Wonder Woman was inspired by Margaret Sanger (and other suffragists)

Creator William Moulton Marston, a psychologist, was deeply interested in gender dynamics, women’s rights and the suffragist movement.

He also fell in love with one of his students at Tufts, Olive Byrne, who eventually lived in his house with him and his wife in a sort of polyamorous relationship. Byrne happened to be Sanger’s niece, and Byrne’s mother, Ethel, and Sanger together opened what eventually became the first Planned Parenthood in 1916.

When Marston hired a woman named Joy Hummel to help him write Wonder Woman, Olive Byrne handed her one book to use as background: Margaret Sanger’s Woman and the New Race.

2. There’s a reason she’s bound up all the time

A recurring plot point in the early Wonder Woman comics was that if the superhero was bound by a man in chains she would lose all her Amazonian powers. So Wonder Woman was bound—a lot. This choice was partly inspired by the suffragists who chained themselves to buildings during protests and used chain symbolism to represent men’s oppression of women. But Marston was also preoccupied, perhaps even obsessed with, bondage.

He had a theory that women enjoyed submission and bondage and teaching young girls of that virtue was one of the purposes of the comic: “This, my dear friend, is the one truly great contribution of my Wonder Woman strip to moral education of the young,” Marsten wrote to his publisher after he was accused of sadism. “The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being found—enjoy submission to kind authority, wise authority.”

Wonder Woman’s subjugation was extremely controversial: Wonder Woman was banned in the 1940s because of the overt sexual nature of both her dress and the sexual nature of her near-constant bondage.

3. Wonder Woman was partly a response to the rise of the Nazis

The first comic book superhero, Superman, hit the stands in 1938. But shortly thereafter, comics came under fire: critics said Superman could be interpreted as a fascist—an all-powerful ubermensch that would have a negative influence on American children. (Remember, the rise of the superhero coincides with the rise of Nazi Germany.) Parents demand that the books be burned.

Superman publisher, M.C. Gaines, reads an article written by Olive Byrne for Family Circle saying that comic books might be good for kids. Gaines asks Marsten to help him save comic books, and Marston recommends a female superhero, reasoning that comic books are too violent and need a touch of femininity. Enter Wonder Woman.

4. The Lasso of Truth had a real-life parallel in Marston’s life

In the Wonder Woman comics, the heroine’s Lasso of Truth forces anyone in its snare to be honest. The weapon was likely inspired by Marston’s own creation of the lie-detector test in 1913. The basic test consisted of taking someone’s blood pressure as they answered questions. Any elevation in blood pressure signaled a subject’s guilt. In 1923, Marston fought to have results of his updated lie detector test used in courtrooms. But the courts rejected the machine, citing too high a frequency of error.

Marston was none-too-happy with this conclusion. In an autobiographical moment in the comics, Wonder Woman tries to get confessions made with the help of her Lasso of Truth admissible in court.

5. Wonder Woman was designed as a feminist icon

Anyone who has read Wonder Woman comics will be able to recognize the feminist underpinnings of her story. But readers probably don’t know that Marston broke from the rest of popular culture by asserting not only that kids would be interested in reading a comic about a woman but that she would be essential to their education in teaching them about gender equality.

“Like her male prototype, ‘Superman,’ ‘Wonder Woman’ is gifted with tremendous physical strength,” Marston wrote in the press release announcing her creation. “‘Wonder Woman’ has bracelets welded on her wrists; with these she can repulse bullets. But if she lets any man weld chains on these bracelets, she loses her power. This, says Dr. Marston, is what happens to all women when they submit to a man’s domination.”

He concludes: “‘Wonder Woman’ was conceived by Dr. Marston to set up a standard among children and young people of strong, free, courageous womanhood; and to combat the idea that women are inferior to men, and to inspire girls to self-confidence and achievement in athletics, occupations and professions monopolized by men.”

6. Despite that, she started out in the Justice Society as a secretary

Wonder Woman was admitted to the Justice Society with heroes like The Flash and Green Lantern after a survey of comic book readers found that the vast majority of girls and boys wanted her there.

But in a 1942 comic penned by Justice Society writer Gardner Fox, all the superheroes get to go off to fight the Nazis, except for Wonder Woman who must stay home and reply to the mail. Marsten was, of course, infuriated by this turn of events.

7. Wonder Woman has run for president in the comic books twice

Wonder Woman ran for office in a comic book written by Marston in 1943, and then again in a cover story in Ms. magazine in 1972. She didn’t win either time. Maybe she should try for 2016.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com