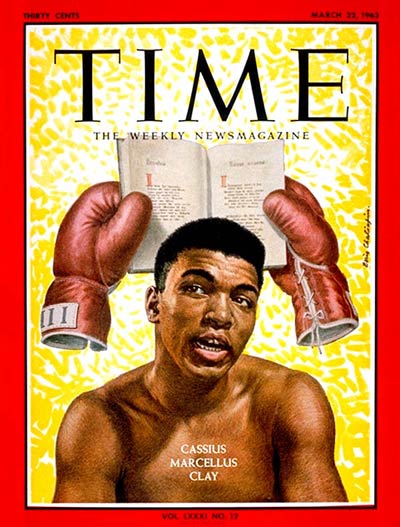

You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. This story originally appeared on the cover of the March 22, 1963, issue of TIME. This piece—reported and written by Nick Thimmesch and Charles Parmiter—ran unbylined, as most did during that period. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

The Clays of Louisville are an old Kentucky family. Not rich, maybe, like the folks who play pool in the Pendennis Club and chew mint leaves on the veranda at Churchill Downs. But the Clays have been there for six generations—ever since their ancestors worked as slaves on the plantation of Cassius Marcellus Clay, who was Lincoln’s Minister to Russia. They like the name, and they like Louisville, and they have a red brick house with five rooms, all of them on one floor. It’s got wall-to-wall carpeting in every room and a picture painted right on the white plaster wall in the living room.

Old Cash Clay did that mural himself. Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr. is a sign painter. Up there where it says KING KARL’S THREE ROOMS OF NEW FURNITURE on Market Street—he did that, just as he painted A. B. HARRIS, M.D., DELIVERIES & FEMALE DISORDERS on Dumesnil Street, Louisville. His son, Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., has just turned 21 and has far larger ambitions. “I’m gonna drive down Walnut Street in a Caddy on Derby Day.” he says, “and all the people will point and say, ‘There goes Cassius Clay.’ Pretty girls will be there, and I’ll smell the flowers and feel the nice warm night air. Oh, I’m cool then, man. I’m cool. The girls are looking at me, and I’m looking away.

I’m wanting to know them worse than they want to know me—only they don’t know it.” By Derby Day next year, Cassius figures, he will be the heavyweight boxing champion of the world.

“I’m the Greatest.” Some people think Cassius Clay talks too much. But Cassius just laughs, and keeps on talking. Sometimes he talks in doggerel:

This is the story about a man

With iron fists and a beautiful tan,

He talks a lot and boasts indeed

Of a powerful punch and blinding speed.

Sometimes he sticks to prose. “I’m beee-ootiful,” he croons. “I’m the greatest. I’m the double greatest. I am clean and sparkling. I will be a clean and sparkling champion.”

Cassius Clay is Hercules, struggling through the twelve labors. He is Jason, chasing the Golden Fleece. He is Galahad, Cyrano, D’Artagnan. When he scowls, strong men shudder, and when he smiles, women swoon. The mysteries of the universe are his Tinker Toys. He rattles the thunder and looses the lightning. “I was marked,” he says. “I had a big head, and I looked like Joe Louis in my cradle. People said so. One day I threw my first punch and hit my mother right in the teeth and knocked one out. If you don’t believe me, ask her.”

Odessa Grady Clay is a short, pillowy woman with freckled fawn skin and an expensive orthodontist. Cash never gave her a bit of trouble. She likes to talk about him as a baby. “The first thing he said was ‘Gee-gee,’ and that’s what people in the family still call him: Gee. Later he said that Gee-gee stood for Golden Gloves, which he was going to win.” Around Grand Avenue, Cassius was known as a prodigious eater, a pretty good rock fighter, and a deadeye marble shooter—when his parents let him out of the house. “Don’t you take one more step,” his mother ordered one day, as Cassius started down the front steps. Deliberately, he took one—just one —more. His mother said. “Daddy will strap you,” and sent him to bed. Cassius used to dream that some day he would be big enough to walk around the block all by himself and not worry about that one step. And he talked about “getting a wheel and wheeling around that block.”

“That Little Smart Aleck.” Dreams came easy in Louisville’s West End. “Why can’t I be rich?” Cassius once asked his father. His father touched him on one pecan-colored hand and said. “Look there. That’s why you can’t be rich.” But at twelve. Cassius got his “wheel.” It was a shiny $60 bicycle, and he proudly pedaled off to a fair at the Columbia Gym downtown. When the show was over, the bike was gone. In tears, Cassius sought out Policeman Joe Martin. “If I find the kid who stole my bike.” he said, “I’ll whup him.” Martin told him that he’d better learn how to box before he went out looking for a fight, and offered to let him join the boxing classes he ran in the gym.

Cassius never did get his bike back. But six weeks later, he got in a ring with another twelve-year-old, a white boy, and beat him. Then he knew everything was going to be all right. The salesmen in the Cadillac showroom downtown got a big laugh at the little Negro, face pressed against the glass, gazing wistfully at the glittering cars inside. “All Cassius talked about was money—turning pro,” says Martin. “At first, I didn’t encourage him. A year later, though, you could see that little smart aleck had a lot of potential.”

Cassius skipped rope for hours to toughen his legs, flailed away at a heavy bag to put power into his punches, sparred with his own mirrored image to quicken his timing and reflexes. There was one terrifying moment at 15 when he flunked a prefight physical. “Heart murmur.” said the doctor. But nothing came of it. Cassius rested for four months, then started, fighting again. On weekends, he wandered about like a nomad, taking on all comers in amateur tournaments all across the U.S.

Cassius’ permanent record at Louisville’s Central High School lists his IQ as “average,” but when he graduated in 1960, he ranked 3761)1 in a class of 391. He only got into trouble once. He hit a teacher with a snowball and was called to stand up before a disciplinary board. He was terribly sorry, he said. Then he calmly told all three of them he was going to be the heavyweight champion of the world.

The Great Gamble. By 1960, when he was 18, Cassius had piled up 108 amateur bouts, and lost only eight. He won six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles, two national Golden Gloves championships, two national A.A.U. titles. “I’m going pro,” he told Martin. But the cop said wait. “In boxing,” he counseled, “the Olympic champion is already as good as the No. 10-ranked pro.” Reluctantly, Cassius boarded the plane for San Francisco and the Olympic trials. Over Indiana, the plane ran into a thunderstorm. Cassius was petrified. He slumped down in his seat, squeezed his eyes shut, and passengers near by could hear him praying over the roar of the engines.

When he won at San Francisco, Cassius threw away his round-trip plane ticket, borrowed money from a referee, and took a train home instead. The Olympics were out, he told Martin. No boat berths were available, and Clay would not fly. Martin sat him on a park bench, told him that the Olympic gold medal was his only chance to be wealthy and famous. “You’ll have to gamble your life,” he said. “Your whole future depends on this one plane ride to Rome. You’ll have to gamble your life.” Cassius agreed. It was a big gamble. But he got on the plane. Besides, in Rome, with that name how could he miss?

There were times when people wondered if he was real. Crowds stopped to gawk at the tall, brown gladiator as he ambled along the Via Veneto, grinning, waving, talking to everybody whether they understood him or not. He captured Bing Crosby and went everywhere with him arm in arm. He posed with Heavyweight Champion Floyd Patterson, shook hands solemnly, and crowed: “So long, Floyd, be seein’ you—in about two more years.” He brushed off a Russian reporter who prodded him about the plight of U.S. Negroes: “Man, the U.S.A. is the best country in the world, counting yours. I ain’t fighting off alligators and living in a mud hut.” In the Olympic Village, he swarmed over foreign athletes, yelling “Say cheese!” while he snapped photos, swapped team badges, slapped backs, and winked at pretty girls. They loved him.

If there had been an election, he would have won in a walk.

Fighting as a light heavyweight at 178 lbs., he knocked out a befuddled Belgian, flicked past a stolid Russian, an Australian and a Pole. “I didn’t take that gold medal off for 48 hours,” he says. “I even wore it to bed. I didn’t sleep too good because I had to sleep on my back so the medal wouldn’t cut me. But I didn’t care. I was the Olympic champion.”

Two at $7.95. On his way to Louisville, the conquering hero stopped to let New York pay its respects. He stayed with Joe Martin in a Waldorf Towers suite that belonged to William Reynolds, vice president of the Reynolds Metals Co.—next door to the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Reynolds asked him if he had brought back any presents for his family. Cassius said no, so Reynolds told him to go out and get some. He picked out a $250 watch for his mother, a $100 watch for his father, a $100 watch for his brother. Still wearing his gold medal around his neck, Clay ate at the Waldorf-Astoria (“The steaks were $7.95.” says Martin, “and Cassius always had two”), toured Greenwich Village looking for beatniks, and whooped delightedly when passers-by recognized him. Tapping a startled cabby on the shoulder, he said: “Why, I bet even you know that I’m Cassius Clay, the great fighter.” Then he bought a bogus newspaper in a penny arcade. The headline: CASSIUS SIGNS FOR PATTERSON FIGHT. “Back home,” explained Cassius, “they’ll think it’s real. They won’t know the difference.”

Louisville gave Cassius a welcoming parade that “crippled the town.” He bought a “rosy pink” hardtop Cadillac on time. And he signed to fight his first professional bout—a six-rounder with a former smalltown West Virginia police chief named Tunney Hunsaker. “He’s a bum,” confided Cassius. “I’ll lick him easy.” But he still got up at 5 a.m. every day to run at least two miles in Chickasaw Park, and he boxed a few fast training rounds with his younger brother Rudolph.

Cassius had not fought one round as a pro; yet each day’s mail brought a new batch of offers. IF YOU DESIRE TO HAVE EXCELLENT MANAGER, CALL ME COLLECT TONIGHT, wired Archie Moore. Pete Rademacher, an ex-Olympic champion who was knocked out by Patterson in his pro debut, wanted to manage Clay. So did Patterson’s manager, Cus D’Amato. But Cassius was looking for something classier. At first, Sportsman Billy Reynolds seemed to have the inside track. There was only one catch: Reynolds wanted to give Sergeant Martin “a piece of the action.” Clay refused. “Martin’s amateur,” he said. “He can’t teach me any more. I need the top-notch people.”

Three days before the Hunsaker fight, Clay signed a contract with a syndicate of eleven white businessmen—ten from Louisville, one from New York, all but four millionaires. That was class, man! Organized and run by William Faversham Jr., 57, sometime actor, son of the matinee idol, now a vice president of Brown-Forman Distillers (Jack Daniel’s, Old Forester, Early Times), the syndicate includes Faversham’s own boss, W. L. Lyons Brown, and William Cutchins, president of Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. (Viceroys, Raleighs). Terms of the deal: a $10,000 bonus, a salary of $4,000 a year, all expenses paid, and a fifty-fifty split of all purses.

Minor Disagreement. Could he fight? The syndicate hired veteran Trainer Angelo Dundee to turn the amateur into a pro. “I smoothed Cassius out and put some snap in his punches,” says Dundee. “I got him down off his dancing toes so he could hit with power.” Says Clay: “Dundee gave me the jab. But the rest is me. What changed the most was my own natural ability.” Either way, what happened next was a surprise. “If anyone had told me a year ago that Cassius would develop into an international figure,” says Tobaccoman Cutchins. “I would have said he was smoking marijuana.”

Cassius won his first six fights, five by knockouts, and most of them before the fourth round. He was ragged enough to make his managers blush, but he was 6 ft. 3 in. tall, weighed 195 lbs., and he seemed to be growing as fast as he talked. He also had the niftiest pair of legs since Sugar Ray Robinson. One day in February 1961, he showed up in Miami, where Ingemar Johansson was training for his third fight with Floyd Patterson. Could he spar a little? Cassius asked innocently, and proceeded to dance rings around Johansson. The big Swede went into a slow boil. “What does this kid do?” growled Johansson. “Ride a bicycle ten miles a day?”

Here Comes the Band. A few more fights and, suddenly, people started to take Cassius seriously. Boxing had been a bore for years—ever since the retirement of Rocky Marciano, a real, hairy-chested puncher. The mobsters and their stable of dull pugs were driving the fans away. But here was Cassius, young, handsome, as brassy as a Dixieland band. He raced around like a candidate for mayor in every city he hit, appearing on radio, TV, grabbing headlines by the handful with his talk about how “great—real great” he was. “The only ones I send away,” he grinned, “are those guys from the little radio stations—they put you on at 4:30 in the afternoon when no one’s at home and no one’s listening.” Sportswriters started coining names for him—”The Louisville Lip,” “Mighty Mouth,” “Cassius the Brashest.” People who hadn’t been to a fight in ten years began turning out to see him box. Half of them adored him; half wanted to be on hand when the loudmouth got his comeuppance. Everyone wanted to know what happened next.

In Louisville, the gate was 3,500 and $12,000 when he kayoed Alex Mitoff. In Los Angeles, 12,000 fans watched him knock out Alejandro Lavorante in the fifth round. “I only wish.” sighed a California matchmaker, “that Cassius Clay were quadruplets.” Even Jack Dempsey was impressed: “I don’t care if this kid can’t fight a lick. I’m for him. Things are live again.”

As the knockout record climbed to nine, ten. then eleven. Cassius started spouting poetry and naming the round in which he would “annihilate” his hapless opponent.

They all must fall

In the round I call.

That made it even better. He got a fight with bold old Archie Moore, who was working on his 45th knockout when Clay was born. Quoth Cassius:

Archie’s been living off the fat of the land

I’m here to give him his pension plan

When you come to the fight, don’t block the aisle and don’t block the door

You will all go home after Round Four.

At 1:35 of the fourth round, tired old Archie was down for the count, and Cassius was ready with another poem:

Some got mad

And some lost money

When I ripped home that right

As sweet as honey.

When Clay knocked out Charlie Powell, a sometime pro football player, in the third round—just as he promised—people started saying that he had called the shot in all his knockouts. The experts were mesmerized. Maybe, just maybe, he really was the greatest. Cassius soared to No. 2 challenger for the championship, just behind Floyd Patterson, and the papers were full of stories about his clever feints, quick hands and swift legs. “Clay has such good movements that he can make you do exactly what he wants,” said onetime Heavyweight Champion Jack Sharkey. “Great! Great!” nodded Middleweight Paul Fender. “He’s the first heavyweight I’ve ever seen who can get hit with one punch and be gone before the second one comes.”

“That Big Ugly Bear.” Shooting for the moon. Cassius started talking up a storm about a championship fight with Sonny Listen, the mountainous, oft-arrested badman. who destroyed Patterson in a farce of a fight last September. “That big ugly bear,” scoffed Cassius. “I hate him because he’s so ugly. I’ll murder that bum.”

Three weeks ago, the two met in Miami Beach’s Fifth Street Gym, where Clay was training for his 18th professional fight and Listen was training for his return bout with Patterson. Cassius started heckling. “You ain’t so hot,” he sniffed. “Yeah?” snarled Liston. “I could leave both legs at home and beat you.” Finally Cassius decided, “I can lick you,” and began to climb through the ropes. Sonny wheeled and charged. Back through the ropes tumbled Cassius, chuckling happily. “Get him the hell out of here,” said a Liston adviser. Raged Liston: “I’m not training for Patterson—I’m training for Clay.”

But first there was a trip to New York and that 18th fight, 18th victory and 15th knockout to dispense with. The match was against Doug Jones, a quiet young New Yorker, who at 26 ranked No. 3 in the heavyweight listings. He looked puny beside Cassius—188 Ibs. to Cassius’ 202. only 6 ft. tall to Cassius’ 6 ft. 3 in. But he had won 21 of his 25 fights, and nobody had ever knocked him out.

“I’ll Annihilate Him.” “That Jones!” hooted Cassius. “That ugly little man! I’ll annihilate him! You know what this fight means to me? A tomato-red Cadillac Eldorado convertible with white leather upholstery, air conditioning and hifi. That’s what the group is giving me for a victory present. Can you picture me losing to this ugly bum Jones with that kind of swinging car waiting for me? I get sore, and Jones fall in four.”

He said it everywhere—in the newspapers, over the radio, on the Tonight show. He even said it in the Bitter End, a Greenwich Village poetry-and-coffee house peopled by curiosities in faded jeans anti beards. In his tuxedo, at noon, Clay was a curiosity himself.

My secret is self-confidence, a champion at birth.

I’m lyrical, I’m fresh, I’m smart, My fists have proved my worth.

Marcellus vanquished Carthage, Cassius laid Julius Caesar low,

And Clay will flatten Douglas Jones With a mighty, measured blow.

Madison Square Garden was sold out five days before the fight for the first time in history. In Room 1049 at tne Plymouth Hotel, Cassius Clay was in a happy mood. “The Garden is too small for me,” he crowed. “Where are the big places? That’s what I need. Maybe the Los Angeles Coliseum. I was up in Harlem today, arguing with 500 people on the corner. I get them to come down here and see Cassius in the Garden. Boxing people are paying their way in. They’re wiping off the seats where the pigeons used to sit.”

Like Old Times. The day of the fight Clay had insomnia. He got up at 6:30 slipped silently out of the Plymouth, and walked two blocks to Madison Square Garden. Nobody recognized him staring up at the marquee that read TONIGHT —BOXING—CLAY vs. JONES. Clay eturned to his room, sprawled on the bed. At 10 he was up again, restless, bubbly’ puckish. At the weigh-in, Cassius burst into the room and strode toward the scales —startled laughter in his wake. Even Doug Jones could not resist a smile. There, plastered across the Mighty Mouth, was a 2-in.-wide strip of adhesive tape.

It was still afternoon, but across the street from the Garden, the fight mob began to gather. It was always like that in the old days, when there were fights worth going to and fighters worth talking about. Then the mob gathered on Jacobs Beach, the sidewalk at 49th and Broadway. Now they sit at grey Formica tables in the Garden Cafeteria gulping matzo-ball soup, or at Jack Dempsey’s bar sipping Rob Roys. Promoter Jack Solomon was in from London to see the fight. Lester Collins, ten years a manager and now a California businessman flew to New York because “I heard so much about Clay I had to find out if he’s really that good.” Ernie Braca, Sugar Ray Robinson’s ex-manager, said that even the scalpers were out of tickets. “The wires are red-hot,” he said. “Businessmen that never called before. They’re offering $75 for a $12 ticket. There are 19 million people out there trying to get into 18,000 seats.”

It was supposed to be a Clay crowd. In the Boston Herald, Bud Collins had complained that nobody wanted Jones to win. “It is a holy war,” he wrote. “Cassius, the savior of boxing, against an opponent whom . he calls ‘that ugly little man.’ Where is the good old American sentiment for the underdog?” By fight time there was plenty of sentiment. Half of Harlem trooped to the Garden to root for New Yorker Jones. For other fans rooting against Clay was practically a moral obligation. Prideful Cassius was due for his fall, and they were there to trip him if they could. The lights dimmed. A spotlight caught Jones, a black fireplug of a man, in a yellow and purple robe. The crowd cheered. Then the spot swung around and picked up Clay, dressed all in white—white robe, white trunks, white shoes. The crowd hooted. There was warm applause for the ring introductions—Gene Tunney, Jack Dempsey, Sugar Ray Robinson, Rocky Graziano, Barney Ross, Dick Tiger—champions all. Then more boos for Clay. And still more, as he danced and waved and made faces at his tormentors.

“Get Cassius! Go get him, Doug!” the fans chanted. “Get that loudmouth!” And in the first round, Doug almost did. Cassius leaned back, and a looping right caught him flush on the side of the jaw. Clay’s knees buckled, his eyes glazed, and he grabbed the ring rope for support. Desperately, Clay shot jabs at Jones’s forehead—light, harmless punches designed only to keep Jones at arm’s length, to survive the round. The second was even, and in the third, his head clear now, Cassius took command. He raked Jones with left hooks, and the crowd grew surly and silent. Then it was the fateful fourth the round in which Jones must fall.

He didn’t. Irreverently, he snapped off two stiff lefts, spun Cassius around, and landed a thumping afterthought on the back of his head. Angry now, Cassius retaliated, exhausting his repertory in a flurry of incredibly swift punches that were enough to win him the round but not immortality. The boos followed him back to his corner.

By the end of the eighth round, Clay knew he was not going to knock out Jones. He knew something else too: that he was behind in the fight. Jab, jab, jab, hook hook, hook, he poured it on in the ninth and tenth. A hard right to the face rocked him, but still Cassius kept flailing throwing five punches to every one of Jones’s piling up precious points. The huge crowd’ knowing it was close, waited tensely for the verdict. Announcer Johnny Addie called for the mike. “Both judges score it five … four … one even—for Clay! Referee Joe Loscalzo scores it . . .”

The crowd exploded with a wave of ugly sound that engulfed Addie’s voice t was a good thing: the referee’s card (eight rounds for Clay, one for Jones one even) was absurd. The chant started in the upper balconies: “Fix! Fix! Fix! Fake! Fake! Fake!” A photographer at ringside was knocked cold by a flying object that creased the back of his skull Peanuts rained onto the ring. Casually, Cassius Clay picked up a handful, cracked the shells, and tossed the nuts into his mouth.

On with the Hunt. Not everybody agreed with the crowd. In Miami, where the fight was on closed-circuit TV, Sonny Liston smiled at the catcalls. “He won it,” said Liston. “It was Clay’s fight.” Did Cassius show him anything? Replied Liston: “He showed me I’ll get locked up for murder if I fight him.” Some sportswriters agreed. Feeling that they had been fooled, they turned on Cassius. He had no punch, no stamina, no stomach for the likes of Liston. they said. Others spotted nuggets of greatness. Work, they decided, clean living, experience—given these, Clay has an unlimited potential. In his dressing room, Cassius was as sassy as ever. “The referee was the most accurate,” he said. “See, I’m as pretty as a girl. There isn’t a mark on me.” He was still hunting big game. “I want Liston. He can’t move as fast as Jones. Doug didn’t fall, that’s all. But Liston will still go in eight.”

At Small’s Paradise in Harlem, his victory party was already in full swing when Clay arrived. Pretty girls—”those foxes.” in Cassius’ vocabulary—leaned close for pictures. The band blared. The management rustled up a cake decorated with roses and strawberries, and plunked it proudly under Cassius’ nose. Cassius smiled, then frowned. He pushed the cake away, popped a pill in his mouth. A doctor whispered in his ear. Suddenly, Clay shoved back his chair and lurched out into the night. All at once, people remembered that he was only 21— and for the first time all evening, he was acting his age.

But did everything turn to ashes in his mouth? No sirree. Another day, and Cassius was back home in Louisville, hurrying over to Standard Cadillac Co. to collect his reward. He rushed into the showroom, flung his arms high, and shouted: “Tomato-red Cadillac convertible, I am here!” Tomato-red Eldorado wasn’t there, and there wasn’t one in all of Louisville. But it will be, and in the meantime Cassius could console himself with his $13,500 out of the purse and $10,000 from the 38-city telecast.

As he rode home in a rented Chevrolet, Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. was already working out the details of his next dream. “There ain’t no such thing as love for me,” he mused sadly. “Not while I’m goin’ on to that championship. But when I get that championship, then I’m goin’ to put on my old jeans and get an old hat and grow a beard. And I’m goin’ walk down the road until I find a little fox who just loves me for what I am. And then I’ll take her back to my $250,000 house overlooking my $1,000,000 housing development and I’ll show her the Cadillac and the patio and the indoor pool in case it rains. And I’ll tell her: ‘This is all yours, honey’ ’cause you love me for what I am.”‘

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com