You can book to travel on British Airways (BA) from London Heathrow to Roberts International airport in Monrovia, but the direct flight will take nine hours—and at least 25 weeks—to arrive in the Liberian capital.

In August BA suspended flights to Liberia and Sierra Leone, citing public health concerns amid the spread of ebola in the region. Now, the U.K. carrier has announced its decision to maintain that suspension through the end of March 2015. BA isn’t alone; there are now so few airlines flying into the area that key workers are being forced onto wait lists and lengthy journeys with multiple stopovers. Right now, European travelers hoping to get to Monrovia or Sierra Leone’s capital Freetown must squeeze on to services operated by Brussels Airlines and Royal Air Maroc, or thumb a ride on a military jet.

Nobody would dispute the wisdom of taking the threat of Ebola very, very seriously, but aid agencies warn that a shortage of transportation to and from west Africa, far from containing Ebola, instead risks undermining efforts to quell the epidemic.

At an Oct. 8 Washington press conference with U.K. Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry called for the international community to “step up” efforts against Ebola and stressed the importance of keeping air routes open. It is a point Justin Forsyth, CEO of the U.K.-based charity Save the Children, also emphasizes.

“The main way to defeat the spread of Ebola not just in the region but globally is to get it under control in Sierra Leone and Liberia and Guinea and the best way of getting it under control is to make sure that we can get health workers into the region because they’re not going to have enough capability in these countries themselves,” says Forsyth, whose charity is working with the British military to establish a treatment center in Sierra Leone, as well as setting up care centers in Liberia and training thousands of health workers. “They’re going to need a lot of people coming in, and not all of it by military [flights].”

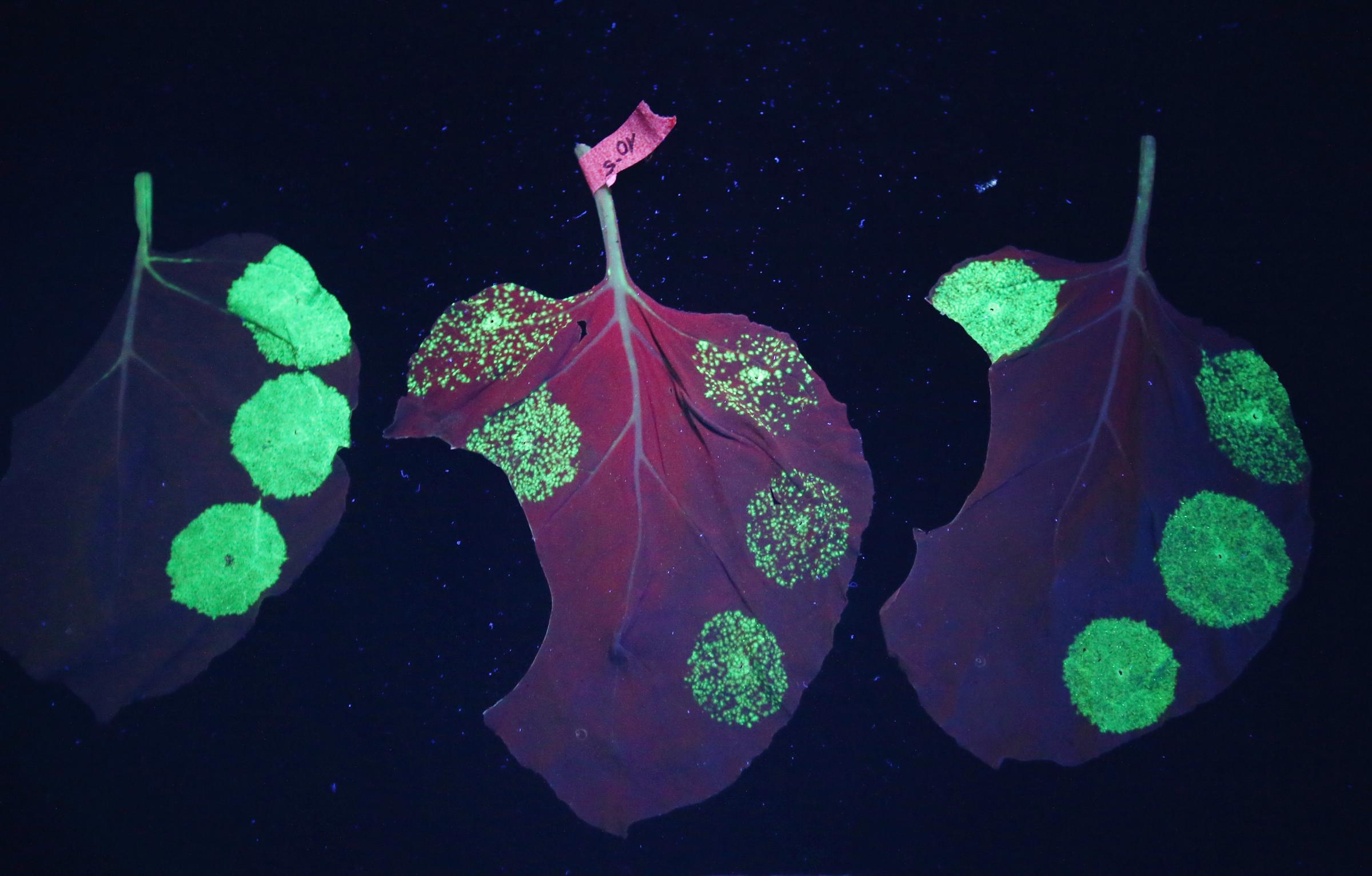

See The Tobacco Leaves That Could Cure Ebola

There have been fresh calls to isolate the disease by further isolating west Africa, after Liberian Thomas Eric Duncan died on Oct. 8 in Dallas, and Spain awaits news of Teresa Romero Ramos, the first person to contract Ebola outside west Africa in this outbreak. Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal had already advocated banning all flights from the region. “We need to protect our people,” he said last week.

On the surface it makes sense. Ebola may not be airborne, but authorities’ assurances that sitting on a plane with an infected person shouldn’t pose a big risk ring increasingly hollow, as Spanish health authorities try to figure out how Ramos caught the disease. She wore protective clothing and followed hospital protocols, though she has said she may have touched her face with a contaminated glove.

Yet in the view of many experts, following the impulse to isolationism is already making countries beyond Africa more vulnerable, not less. Christopher Stokes, director of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in Brussels, told the Guardian “Airlines have shut down many flights and the unintended consequence has been to slow and hamper the relief effort, paradoxically increasing the risk of this epidemic spreading across countries in west Africa first, then potentially elsewhere. We have to stop Ebola at source and this means we have to be able to go there.”

Save the Children’s Forsyth agrees. He recognizes the concerns of airline staff, though, and says “It’s a big decision by anybody to go to work in one of these countries at the moment. We’ve got lots of people stepping forward to do it but it’s not an easy decision.”

The only option, Forsyth believes, is for governments to take the lead. “We need the airline industry to come together. This is where governments have a big role to play, to bring airlines together,” he says. “The other way to do it is to set up an air bridge paid for by governments or the military.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Biden Drops Out of Presidential Race , Endorses Harris to Replace Him

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Stop Feeling Bad About Sweating

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com