Scotland Decides: The Independence Referendum In Photos

The morning after was always going to be rough.

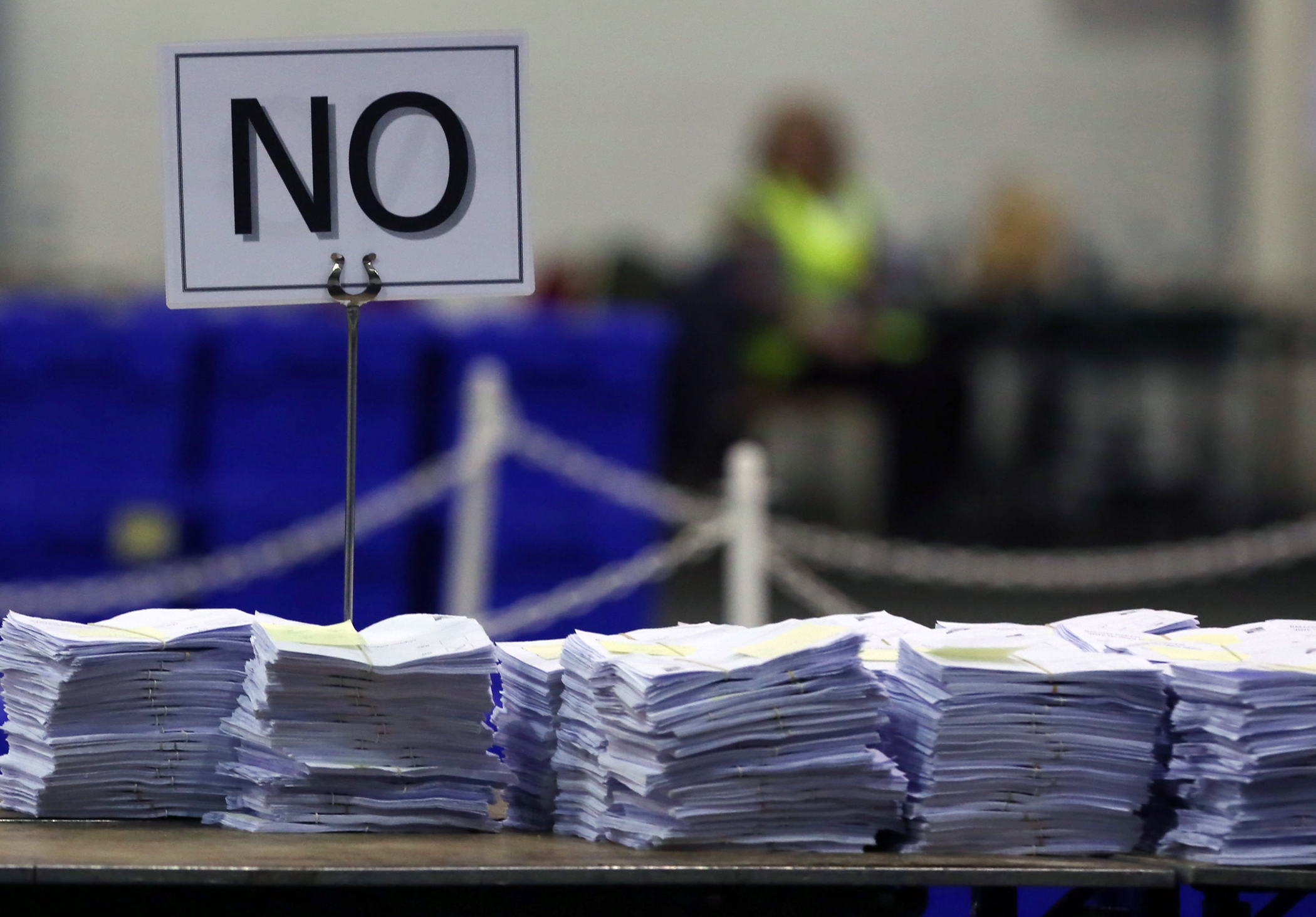

As Scots woke up on Friday morning to the news that 55% of voters had voted against independence and that Scotland was indeed going to remain a part of the United Kingdom, the entire country had to begin a process of reconciliation, or at least, acceptance.

In Edinburgh the day before, voters on both sides of the referendum debate had filled the streets, dressed in T-shirts or wearing buttons that proudly announced which way they were voting. That wasn’t the case on Friday. The streets were quiet, Scots seemed subdued and there wasn’t a “Yes” sticker in sight. Many young men — the demographic most closely associated with the pro-independence movement — refused to talk about the referendum at all.

Even the pro-union voters — who formed a 61% voting bloc in Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital — had a hard time seeing the outcome as a reason to celebrate. “It’s more like dodging a bullet than a victory,” says Scott Dixon, a 34-year-old No voter who works on the offshore oil and gas rigs of the North Sea, adding that he still hoped to see Scotland gain more power from the central U.K. government in London. Similarly, Malcolm Clark, a 61-year-old assistant at a care home, voted against independence, but he also noted the downtrodden atmosphere that had settled over the city. “I think there’s argument to be made for either side of the debate,” he says, explaining why even the unionist voters didn’t feel like celebrating. Besides, “the day after is always a little flat.”

Perhaps softening the blow to disappointed Yes voters, Prime Minister David Cameron vowed early Friday morning to give Scotland more powers to run its own affairs — a pledge he also extended to England and other parts of the U.K. But few Scots seemed confident that the government would actually come through and others were wary about the increased powers for the rest of the U.K.

Lisbet Faragher, a retired Dane who once worked for the European Commission but now lives in Edinburgh with her English husband, voted for independence on Thursday and says the country “missed an opportunity.” And while she’s not surprised that people in England and Wales have started asking for more control from the central government in London she feels “the English and Welsh should have fought their own corner.” Either way, she says she’s waiting to see “if Cameron can keep his promise,” before she celebrates any increased powers.

Ross Tavendale, a 25-year-old digital marketer and Yes voter, is also extremely suspicious of how Cameron’s promises could negatively impact Scotland. “I think the Tories are currently sharpening their knives,” he says, referring to the crop of Conservative MPs who’ve suggested they would attempt to block Cameron from giving Scotland further powers. “I think there will be a large backlash in England and moves will be made to limit any gains we’ve made.”

Others think that although the Yes campaign lost the independence vote, the passionate response from many people across the country is a sign that there will be change to come in the long run. With voter turnout at 86%, many believe that the political engagement sparked by the independence question could increase political participation and energy more generally in Scotland. “I think people will be quite demanding [of their politicians] now,” says Dixon. Others pointed to the keen political interest and turnout among 16 and 17-year-old voters, and said they had hopes for the younger generations getting involved in politics. Rebecca Wood, a 35-year-old youth development worker and Yes voter, says she’s certain the energy raised by the referendum means “there will be a push for more”.

Some politicians and church leaders have expressed concern that the passion generated by the independence question — and the unavoidable disappointment felt by a large portion of the population — could cause lasting damage in the communities. The Church of Scotland is even planning a service of reconciliation at Edinburgh’s St Giles’ Cathedral on Sunday.

But while there was a pervasive sense of disappointment across large parts of Edinburgh, in the immediate wake of the referendum the majority of the people who spoke to TIME didn’t believe that the vote would cause a rift among Scots. Many people claimed that Scotland would simply “get on with it.” Tavendale said he thinks there might be “scuffles at the weekend when people are drinking, but it will die down.” Most people said that Scotland would continue to see itself as a united country.

But as time goes on, and the reality of the vote settles in, it’s hard to say just how Scots will feel about their country and one another.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com