In college, the best grades are usually considered to be the product of sleepless nights. Now, universities nationwide are setting up designated rooms for napping or expanding existing spaces to show students that they don’t have to sacrifice sleep to do top work.

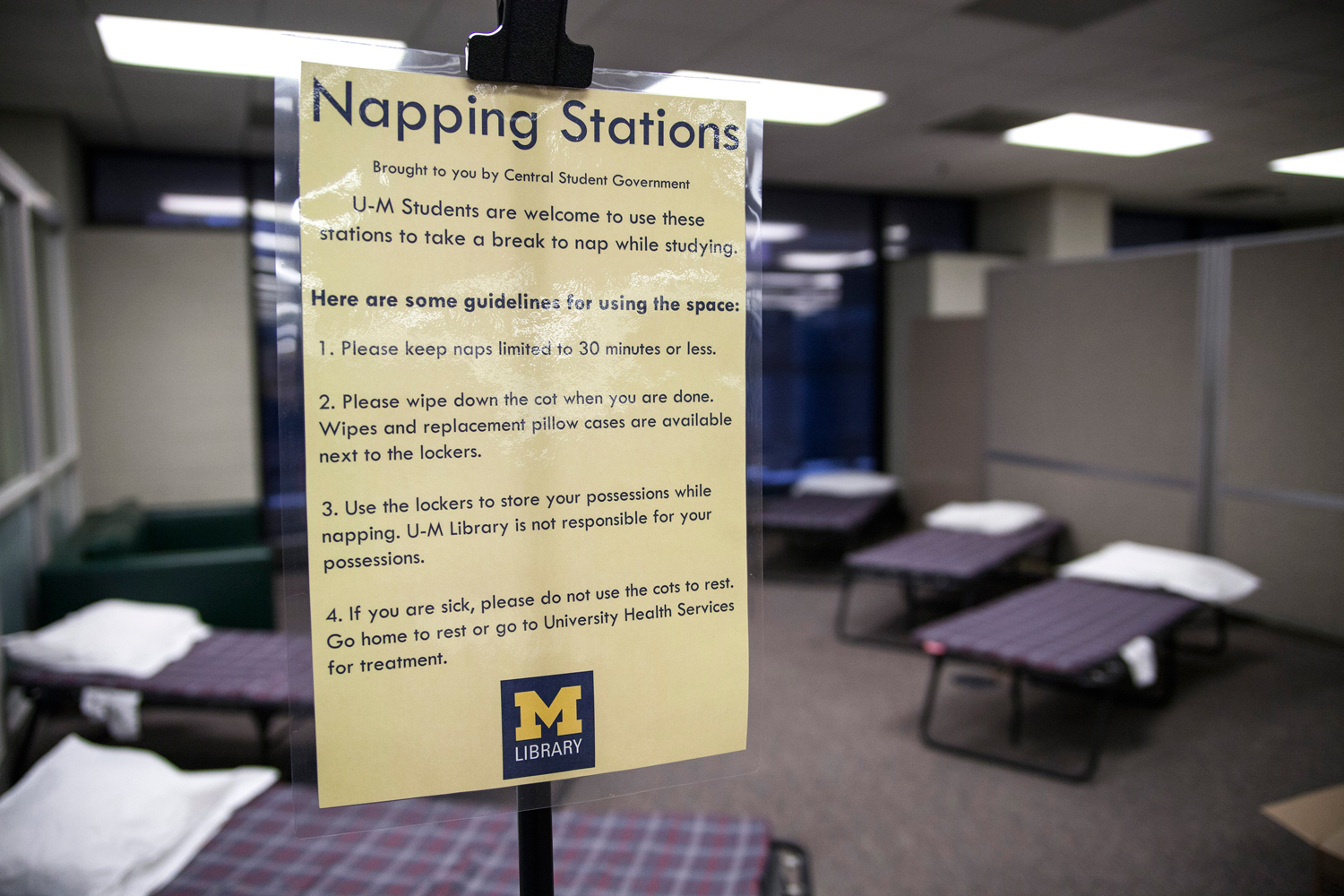

The University of Michigan in Ann Arbor is the latest school to make headlines for piloting a napping station through fall 2014. In the walk-up to finals on April 23, 2014, six vinyl cots and disposable pillowcases were placed on the first floor of the University of Michigan’s Shapiro Undergraduate Library, which is open 24/7. First-come, first-serve, with a 30-minute time limit on snoozing, the area was the brainchild of rising senior Adrian Bazbaz, 23, an aerospace engineering major who came up with the idea as a member of U-M Central Student Government after watching countless students fall asleep in front of the library computers. “They’ll just put their backpacks on the table and lie on them,” he says.

Ryan DeAngelis, 21, a senior majoring in neuroscience and philosophy, used the napping station twice during finals, each time around 12:30 a.m.-1:00 a.m. for about 20 minutes while writing a 12-page paper about metaphysics. Even though he lives on campus, he says the library setup helped him get the job done because he was in a place where the people around him were studying.

“It forces you to stay there,” he adds. “You’re going to wake up in 20 minutes and keep working, but if you go back to the dorm, you’re tempted to fall asleep and then maybe procrastinate ‘til the morning.”

Pod Life

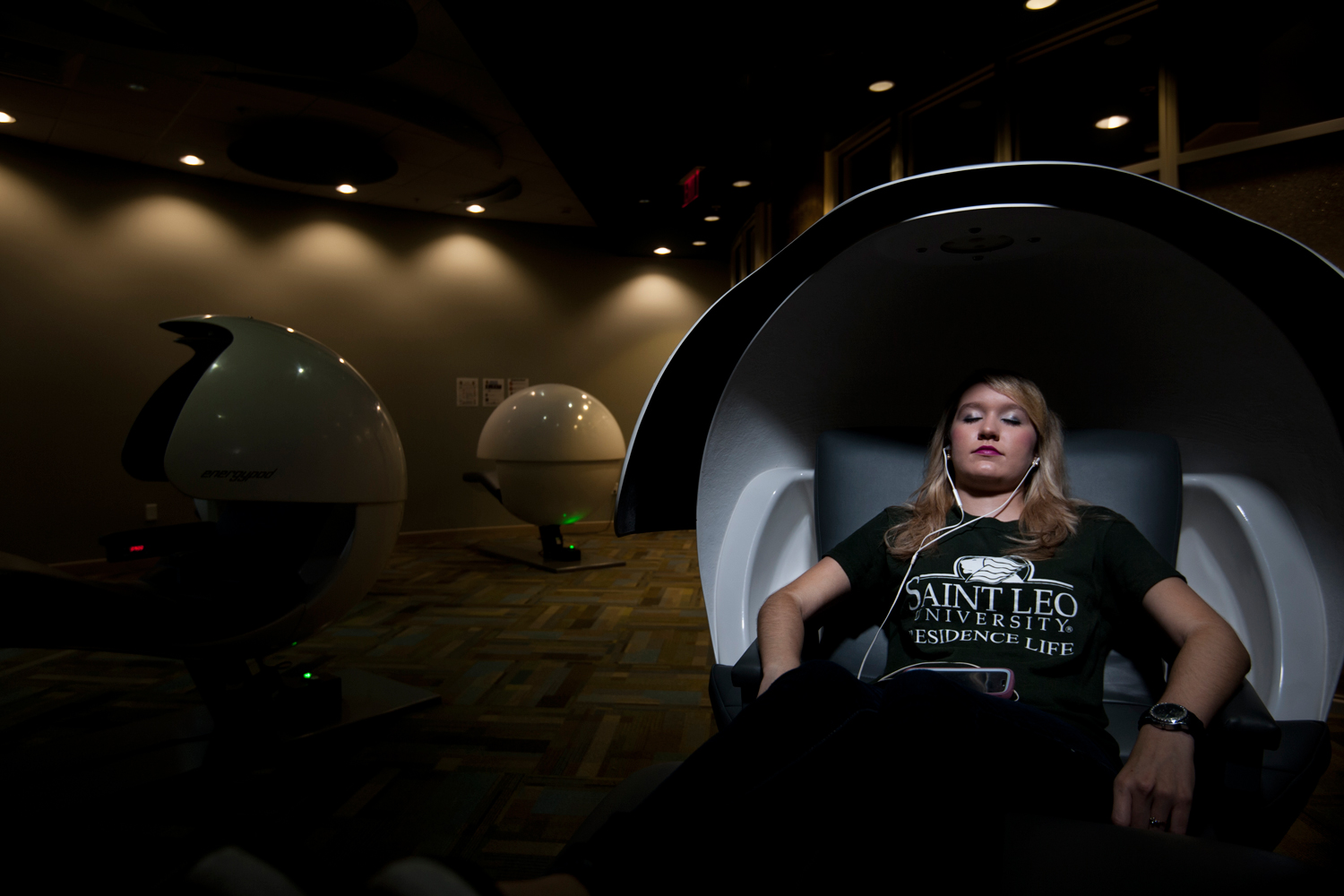

In August, the library started testing out a MetroNaps Energy Pod, a futuristic chair designed for napping, and is thinking about ordering more, according to Stephen Griffes, Operations Supervisor. Popularized by Google, it keeps the sleeper’s legs elevated, and a dome on top ensures privacy. Users can either select the pre-programmed 20-minute nap cycle or customize the duration. And they can listen to soothing music as the machine gently vibrates.

“We are seeing a lot of interest, in particular, from large universities, those with significant commuter student bodies, and graduate medical institutions,” according to an email statement from Christopher Lindholst, who co-founded MetroNaps with Arshad Chowdhury. “Typically the installations go into campus centers and/or the libraries, except in graduate medical institutions where they go directly into the teaching hospitals.”

Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) has maintained two EnergyPods for commuter students at each of its Savannah and Atlanta campuses since 2006 and is adding four to its Hong Kong campus this fall. At Saint Leo University in Central Florida, the residence hall Apartment 5 maintains four in a “relaxation room” intended for the 30% of students who commute.

But the cost of the pods, which ranges between $9,995 and $12,985 (depending on the model features), may be too steep for some schools. In March 2014, Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi installed a less expensive $4,000 “sleep pod” made by the U.K. company PodTime in the Island Hall Gym. Students sign up for a 30-minute interval, grab a sheet and then climb into what basically looks like a white tube with a vinyl mattress inside.

A Room of One’s Own

While Google maps of the University of Texas-Austin, University of California-San Diego, UC-Santa-Barbara, UC-Davis, and Macalester College review the best places to snooze on campus based on noise levels and foot traffic, some students appreciate the privacy that nap rooms afford.

“I used to go into the library and find a comfy chair in between classes to close my eyes for a while, but I always felt awkward sleeping in front of people,” says Meredith Pilcher, 22, a senior graphic design major at James Madison University (JMU) in Harrisonburg, Va., who, at least twice a week, would doze off on a giant bean bag while listening to classical music in a place called “The Nap Nook.” The room on the first floor of the school’s Festival Conference and Student Center opened in September 2013 with six black, microsuede bean bags and antimicrobial pillows that students could reserve online in 40-minute intervals.

Since more and more students seem to be using it – 2,500 naps were taken there between September 2013 and May 2014 – two white noise machines are being added, plus two more bean bags and faux leather covers for them so that they’re easier to wipe down.

“Heavy workloads make you choose between an A and sleep, and I wanted to change the perception that napping was a lazy behavior,” says Caroline Cooke, 22, who founded The Nap Nook at JMU when she was a senior psychology major.

Health Benefits of Napping

Sara Mednick, assistant professor at University of California-Riverside and author of Take a Nap! Change Your Life, says catching some z’s can boost productivity. In fact, she says the most productive kind of nap is a 60-90 minute one taken 8-9 hours after waking up: “Ninety minutes affords you all of the different sleep stages shown to be important for cognition, memorization, creativity, basic motor skills and the ability to make decisions in a clever way.”

Understanding that many students are also sleep-deprived because they stay up too late socializing, Mednick argues, “Napping is a survival mechanism for college. It’s probably how students get a lot of their stamina to deal with this insane, 24/7 lifestyle that they’re suddenly thrust into after being home with their parents.”

And no matter how many sodas from the vending machine and cups of coffee college students chug from the cafeteria, caffeine cannot make them feel as rested as well as a nap. “The boost you get from caffeine is good for 15-20 minutes up to a half hour, but sleep is actually taking the recent information that you’ve learned and filing it away for you so you can more effectively take in new information,” says Robert Stickgold, an associate professor of psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School.

There’s even research that suggests sleep can be the difference between passing and failing out of school. A study published online in the journal Sleep this summer found sleep-deprived undergraduates were more likely to get worse grades and drop a course than their well-rested fellow students. Poor sleep was found to be as powerful as binge drinking, and more powerful than marijuana, in predicting who would have academic problems, according to co-authors Roxanne Prichard and Monica Hartmann, professors at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota.

“Colleges provide resources about hand-washing, drugs, alcohol, to help students stay healthy, but they’re not doing as much to address poor sleep,” says Prichard.

The Future of Nap Rooms

As colleges and universities compete for state-of-the-art amenities, encouraging drowsy students to nod off in a separate room arguably keeps campus buildings looking spiffy, and thus more appealing to prospective students. As Glenn Wallace, SCAD’s Senior Vice President for University Resources, put it, “No one wants to walk around and see people laying on the floor with their mouths open.”

Now what do parents, the people who foot most of the ever-rising bills for college, think about paying for napping pods or rooms? Shortly after Cristina Ley, 21, dozed off at Michigan’s napping station during finals, she was woken up by a phone call from her mom, whom she had been venting to earlier in the night about the stress of writing a paper. “She was like, ‘What do you mean you’re napping in the library?’ And I told her about it, and she was like, ‘Oh that’s really cool!'”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com