Alex Hawkinson’s house knows how to make his day.

As the 41-year-old father of two gets out of bed, the lights flicker on and the air temperature starts to warm. He walks down the stairs, and a Siri-like voice greets him from his Sonos sound system: “Today’s forecast is …” By the time he reaches for his mug of coffee–it began brewing automatically–that woman’s voice has morphed into an NPR broadcast, and Hawkinson is checking his phone, which will receive a text if his 4-year-old son runs out the front door before breakfast. Should Hawkinson open the liquor cabinet, intentionally or not, his house will object. “Isn’t it a wee bit early?”

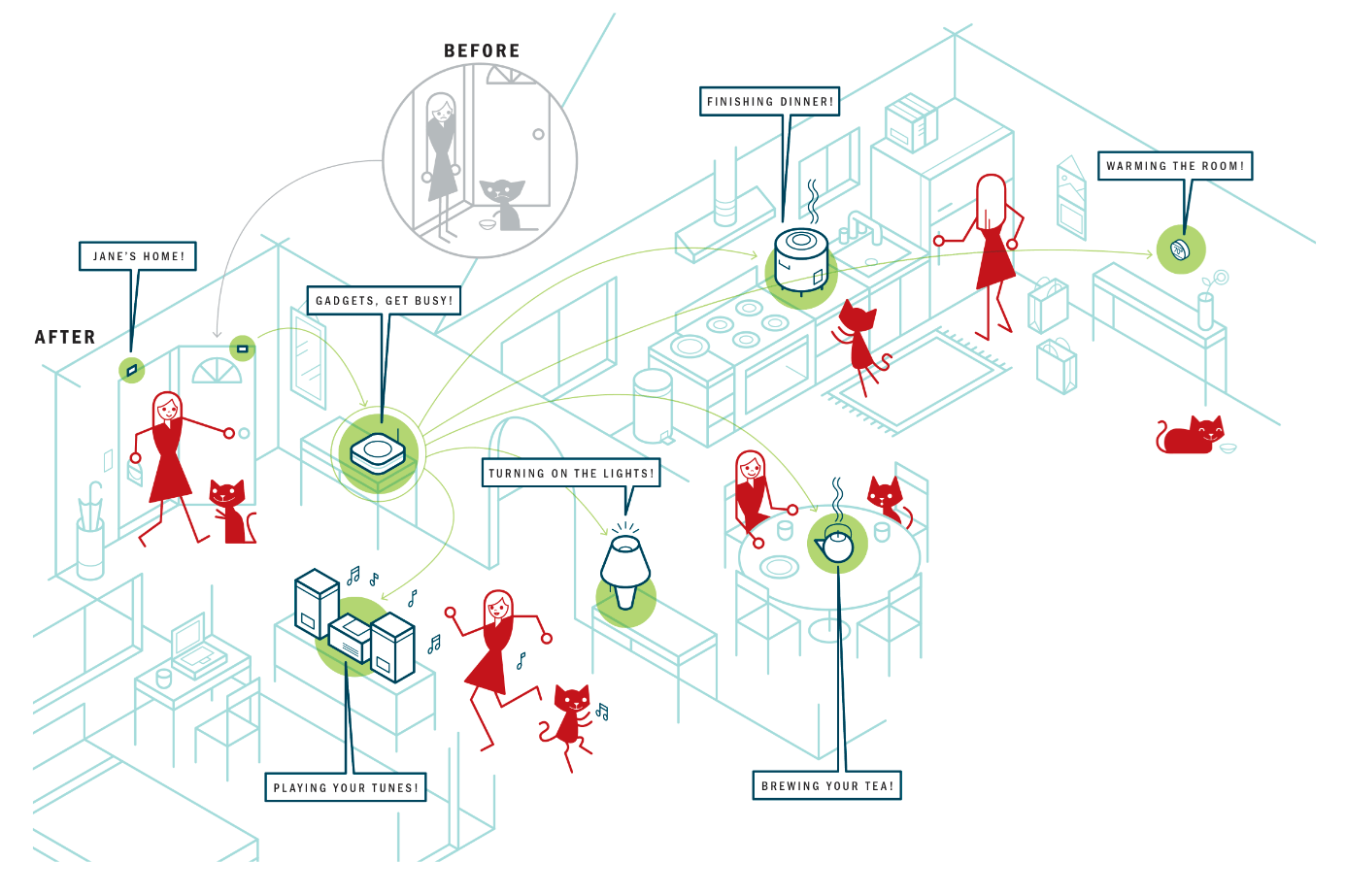

If Hawkinson has his way, every family in the U.S. will be living like this within the next decade or so. And it will be largely thanks to his company, SmartThings, which has built a first-of-its-kind platform that allows the objects in your home–doors, locks, lightbulbs, even sprinkler systems–to talk to one another and prioritize your needs. Its only requirements: a smartphone, a $200 starter kit (including sensors and a hub they sync with) and a wild imagination.

“We’re at the outset of this wave where … your home can give you security, peace of mind and more,” Hawkinson says. “Eventually, everything that should be connected will be connected.”

If this narrative sounds familiar, that’s because it is: companies have been promising the dawn of the smart home–a futuristic dwelling full of gadgets working seamlessly to satisfy your every whim–since the ’50s. Yet early efforts failed to deliver because of clunky tech and consumer wariness.

SmartThings, which launched in 2012, has arrived amid a legitimate sea change in home automation. In the past few years, the rise of cloud computing has made it easier than ever to build gadgets that connect to the so-called Internet of Things, meaning they can be monitored and controlled from afar, usually with their own smartphone app. There’s also been an uptick in the production of sensors and devices that enable you to smartify objects that are dumb. (Think plugging a desk lamp into an adapter controlled by your phone, or rigging a door with a motion detector that pings you about intruders.) By 2018, the research firm IHS Technology predicts, people will have installed 45 million smart-home services. “We’re really starting to see major volume here,” says Lisa Arrowsmith, an IHS associate director. “It’s an exciting time.”

But the race to make those gadgets and sensors work together has only just begun. Much as Google and Yahoo created search engines as a way to bring order to the Internet in the ’90s, startups and established players alike–including Apple, AT&T and Google–are now enabling you to command the Internet of your home. Whoever creates the most compelling platform will not only revolutionize how we live but also command a huge share of what’s expected to be a $12 billion annual business within five years.

SmartThings, though smaller and less resource-rich than the tech titans, is well positioned to lead the pack. Unlike bigger companies, it doesn’t have an established business model to protect, so it can reimagine the connected home from scratch. And unlike other smart-home startups like Revolv, it already has thousands of civilian developers working to make novel apps for the products it connects–enabling you to make your speakers bark, for example, if your cat jumps on the kitchen table.

But to go mainstream, SmartThings and its rivals will have to convince a lot of people that’s it’s safe–and worthwhile–to trust their home life to technology. For all its hype, the full-service smart home is still very niche; less than 1% of U.S. households own that kind of system. And as with the Internet, the idea of extreme connectivity comes with real concerns about security and privacy. As Hawkinson puts it, “How do you avoid the creepy factor?”

Like many great ideas, SmartThings arose from disaster. In February 2011, Hawkinson and his family arrived in Leadville, Colo., for what they thought would be a relaxing weekend at their vacation home–only to find the interior caked in ice. The pipes had frozen and burst, and the repair bill came to $100,000. “How is it possible that someone hasn’t created something I could plug in,” Hawkinson wondered at the time, “that would alert me when something went wrong?”

The veteran entrepreneur gathered some friends and used a holiday slush fund to start developing what would eventually become the SmartThings hub: a wi-fi-enabled device about the size of a smoke detector that syncs with almost any connected gadget or sensor, allowing users to program their homes from a single app. When paired with a moisture detector, for example, SmartThings could be set to automatically text Hawkinson if his pipes burst again–or, perhaps, to cue the theme from Titanic on his sound system.

Within 18 months, the fledgling company had raised more than $1.2 million on Kickstarter (Ashton Kutcher was an early investor), and manufacturers like Quirky, now a General Electric partner, started sending their devices over for testing so SmartThings could ensure compatibility. By mid-2013, SmartThings had shipped more than 10,000 hubs.

Hawkinson was immediately struck by the creativity of his consumers. A couple in Minnesota put presence sensors on their kids’ backpacks so they could locate them. A man in Canada trained his speakers to play an angelic chorus as he approaches his majestically lit scotch collection. Witnessing such applications firsthand, says Hawkinson, “makes you start to see the world … as programmable.”

To get would-be buyers as excited as he is–an imperative in a space mired in skepticism–Hawkinson encourages users to upload their programs to SmartThings’ open platform so that others can browse and download the most popular ones, much as they do with smartphone apps. (Results are tailored to the gadgets and sensors they actually own.) To date, some 5,000 people have shared their gadget tricks–well above figures from any other smart-home platform–and thousands more have tapped them for personal use.

Still, no matter how much SmartThings crows about connectivity, “there is always going to be a segment that doesn’t see the value,” says Arrowsmith. The gadget selection is limited, the setups can be complicated, and legitimate fears of cybercriminals commandeering your smart locks and cameras have made people wary of making their homes potentially hackable.

Hawkinson understands those concerns, but he’s also trying to render them moot. To ensure security, he hires white-hat hackers to continuously probe SmartThings’ technology and pinpoint vulnerabilities that must be fixed. To make smartification more seamless, he plans to turn the open platform into a full-service connected-home depot offering DIY video tutorials, links to installation services and more. He also struck a deal with Cross Country Home Services, one of the U.S.’s largest home-warranty providers, to include SmartThings hubs as part of a full-home protection plan. And he’s working with Philips and wearable-tech pioneer Jawbone, among others, to enlarge SmartThings’ arsenal of devices.

The main challenge, however, is raising awareness–about SmartThings and about the perks of connecting your home in general. From that standpoint, the competition from Apple, which is starting to enter the connected-home space, is a good thing. “It’s like Inception,” Hawkinson says. “The more people hear about this stuff, the more they realize, Wow, this previously dumb and totally disconnected thing should be connected.”

Then again, connectivity can’t automate everything. Back at home, Hawkinson describes a SmartThings mode he made for his wife called Aaaawwwwwww Yeaaaah. Once he taps his phone, the lights dim red and the bass of Barry White resounds from the speakers. Alas, he says, that particular trick “has never worked out for me.” But don’t blame SmartThings. “Technically,” he clarifies, “it works every time.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com