You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

Watchers of the U. S. skies last week reported no comet or other celestial portent. In Manhattan no showers of ticker-tape blossomed from Broadway office windows, no welcoming committee packed the steps of City Hall. No call to nation-wide thanksgiving was sounded by Nicholas Murray (“Nicholas Miraculous”) Butler. No overt celebration marked the day with red. Yet many a wide-awake modern-minded citizen knew he had seen literary history pass another milestone. For last week a much-enduring traveler, world-famed but long an outcast, landed safe and sound on U. S. shores. His name was Ulysses.

Strictly speaking, Ulysses did not so much disembark as come out of hiding, garbed in new and respectable garments. Ever since 1922, when the first edition of Ulysses was published in Paris, hundreds of U. S. citizens have smuggled copies through the customs or bought them from bookleggers. But this week, on the strength of Federal Judge John Munro Woolsey’s decision that Ulysses is not obscene (TIME, Dec. 18), Random House was able to publish the first edition of the book ever legally printed in any English-speaking country.

For every first-hand reader of Ulysses there have been scores of second-hand gossipers. Censorship rather than sound criticism has spread its reputation throughout the Western world. What the man in the street has heard of Ulysses has made him prick up his ears. Usually his first question is:

Is it dirty? To answer the man in the street in his own language, Yes. With the exception of medical books and out & out pornography, the only book of modern times that can compare with it for outspokenness in barnyard and backhouse terms is the late D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. But Ulysses is far from being “just another dirty book.” Judge Woolsey decided that its purpler passages are “emetic,” rather than “aphrodisiac”; that the net effect of its 768 big pages is “a somewhat tragic and very powerful commentary on the inner lives of men and women.” But even granting Ulysses a bill of moral health an intelligent adult may well smite his brow and cry:

What is it all about? Trusting readers who plunge in hopefully to a smooth beginning soon find themselves floundering in troubled waters. Arrogant Author Joyce gives them no help, lets them sink or swim. But thanks to the exploratory works of critics, and notably such an exegetical commentary as Stuard Gilbert’s James Joyce’s Ulysses (TIME, Jan. 5, 1931), the plain reader can now literally find out what Ulysses is all about. Lacking the sleuth-nose, the slot-trained paws of scholarship, even an intelligent reader will miss much the first time over the ground. At that, however, the main outlines of the story are plain.

Ulysses opens early on a summer morning (June 16, 1904) on an old tower outside Dublin. Here three young men are living together: Stephen Dedalus. embittered, ambitious intellectual; Malachi (“Buck”) Mulligan, medical student and japer extraordinary; a minor character named Haines. After breakfast Haines and Mulligan walk to the sea and Mulligan bathes while Stephen sets off to his teaching at a boys’ school. At about the same hour one Leopold Bloom, middle-aged Jew who makes his living as an advertisement-canvasser, rises from his bed to cook his wife’s breakfast and bring her a letter from her latest paramour. Bloom knows all about Molly’s constant infidelities, but is too crafty and too resigned to do anything about them. Leaving her in bed, he goes about his day’s business. He visits the public baths, attends a funeral, calls at a newspaper office, has lunch at a pub, drops in at the National Library, goes to Sandymount beach to take the air. In the evening he calls at the Lying-in Hospital to inquire after a friend’s wife who is having a hard delivery. There he meets Stephen, carousing in the common room with some medical students, and joins the party. Bloom takes a liking to Stephen, and when the party breaks up follows him to “nighttown” to take care of him. After a wildly drunken scene in a brothel and a brawl between Stephen and two soldiers. Bloom persuades Stephen to come home with him. When they have had a cup of cocoa in the kitchen, Stephen, now fairly sober, takes his leave. Bloom goes up to bed, where he makes a drowsy but cautious report of his day’s doings and goes to sleep. Molly lies awake, thinking over what he has told her and what they have not told each other. The book ends with her famed soliloquy.

The plainest reader will also see that there is a great deal more to Ulysses than this record of two men’s day in Dublin. Without a key to its plan this stream-of-consciousness Bible, with its elliptical shorthand, its apparently confused and formless method, may well seem an esoteric work of art. Confusing Ulysses sometimes is, but rather from too much plan than too little. The key to the plan is the title.

Why “Ulysses”? Every schoolboy knows the story of the Odyssey, epic-sequel to the Iliad, which recites the ten-year wanderings of the wily Odysseus (Latin—Ulysses) in his long-thwarted attempts to get home to his island kingdom after the siege of Troy. The Ulysses of the Odyssey is a cunning, commonsensible, nervy, not-too-scrupulous man, an opportunist who triumphs at last not so much by virtue as endurance. Joyce first conceived the tale of Leopold Bloom as a short story, only to discover too many possibilities in it. In his strolls down the beaches of literature he stumbled on the Odyssey, an archaic old bottle but still stout, decided it was just the thing for his 20th Century wine. Thus, Ulysses became Bloom, the wanderer in search of home, wife and son. Penelope was his wife Molly, Telemachus, Stephen. Other obvious parallels: Hades, the graveyard; the Cave of Aeolus, the newspaper office; the Isle of Circe, the brothel. A less obvious parallel: the passage between Scylla and Charybdis, Bloom’s walk through the National Library while Stephen and some literary men are discussing Aristotelianism (the rock of Dogma), Platonism (the whirlpool of Mysticism). Ulysses’ slaying of Penelope’s suitors has its counterpart in Bloom’s casting from his mind scruples and false sentiment about himself and Molly. Almost every detail of the Odyssey’s action can be found, in disguised form, in Ulysses.

On a third stratum of Joyce’s book even deeper meanings appear. Stephen represents the intellect, the creative imagination; Mrs. Bloom the earth, the flesh; Bloom the average half-intelligent, half-sensual man. Like ancient Troy, Ulysses is many cities on one foundation. If the plain reader keeps on digging he may discover that each of Ulysses‘ 18 episodes is written in its own style, in which Joyce has tried to blend the minds of the characters, the place, atmosphere, feeling of the time of day. Each episode turns on an organ of the body, an art and a particular symbol. Thus in the 11th episode (the Sirens), the scene of which is the Concert Room at 4 p. m., the bodily organ represented is the ear; the art, music; the symbol, barmaids; the technique, fuga per canonem (repetition and elaboration of a theme, as in music). Without such foreknowledge, no one could make much of this:

“Bronze by gold heard the hoofirons, steelyringing.

Imperthnthn thnthnthn.

Chips, picking chips off rocky thumbnail, chips.

Horrid! And gold flushed more.

A husky fifenote blew.”

A great book? If greatness is measured by universality of appeal, Ulysses cannot be called great. It will never be a bestseller. Old-line critics have mostly found it too hot to handle. But a growing body of modern critical opinion on both sides of the Atlantic has already acclaimed Ulysses as a work of genius and a modern classic. For readers to whom books are an important means of learning about life, it stands preeminent above modern rivals as one of the most monumental works of the human intelligence.

Ulysses is an epic constructed on the principles of solid geometry, a synthetic dissection. Showing a thick segment (in time: 20 hours) of one day’s life in Dublin, it cuts through many a solid slice of human tissue. It slices through “literary” brain cells:

“Ineluctable modality of the visible: at least that if no more, thought through my eyes. Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot. Snotgreen, blue- silver, rust: coloured signs. . . . Airs romped around him, nipping and eager airs. They are coming, waves. The white-maned seahorses, champing, brightwind-bridled, the steeds of Mananaan. . . . The grainy sand had gone from under his feet. His boots trod again a damp crackling mast, razorshells, squeaking pebbles, that on the unnumbered pebbles beats, wood sieved by the shipworm, lost Armada. Unwholesome sandflats waited to suck his treading soles, breathing upward sewage breath. He coasted them, walking warily. A porterbottle stood up, stogged to its waist, in the cakey sand dough. A sentinel: isle of dreadful thirst. Broken hoops on the shore; at the land a maze of dark cunning nets; farther away chalkscrawled backdoors and on the higher beach a dry-ingline with two crucified shirts. Ringsend: wigwams of brown steersmen and master mariners. Human shells. . . . He turned his face over a shoulder, rere regardant. Moving through the air high spars of a threemaster, her sails brailed up on the crosstrees, homing, upstream, silently moving, a silent ship.”

And through lusty arteries: “and the poor donkeys slipping half asleep and the vague fellows in the cloaks asleep in the shade on the steps and the big wheels of the carts of the bulls and the old castle thousands of years old yes and those handsome Moors all in white and turbans like kings asking you to sit down in their little bit of a shop and Ronda with the old windows of the posadas glancing eyes a lattice hid for her lover to kiss the iron and the wineshops half open at night and the castanets and the night we missed the boat at Algeciras the watchman going about serene with his lamp and O that awful deepdown torrent O and the sea the sea crimson sometimes like fire and the glorious sunsets and the figtrees in the Alameda gardens yes and all the queer little streets and pink and blue and yellow houses and the rosegardens and the jessamine and geraniums and cactuses and Gibraltar as a girl where I was a Flower of the mountain yes when I put the rose in my hair like the Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.”

The Wanderings of Ulysses have been longer if less arduous than those of its namesake. Joyce finished his seven-year job of writing it at Paris in 1921, but could find no publisher. Editors Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap printed several installments of it in their Little Review, mailed copies of which were promptly suppressed by the U. S. postal authorities. Then Poet Ezra Pound, good friend to Joyce, introduced him to Sylvia Beach, liberal daughter of a Princeton. N. J. Presbyterian parson, who ran a bookshop in Paris, Shakespeare & Co. Bookseller Beach had Ulysses printed at a French press in Dijon, presented the first copy to Author Joyce on his 40th birthday (1922). In the twelve years since then there have been ten editions in Paris and London. Of the second printing (2,000 copies). 500 were burned by the New York postal authorities. Of the third (500), only one copy escaped the holocaust of-the British customs at Folkestone. Since the U. S. is not a member of the International Copyright Union, there was nothing to prevent any U. S. scalawag from pirating Ulysses and ‘legging copies. Some scalawags did. After the fate that met Joyce’s book of short stories, Dubliners, in his own country (”Some very kind person,” says Joyce, “bought out the entire edition and had it burnt in Dublin” ) there was no chance of publishing Ulysses there. And Joyce had not increased the honor in which Ireland held him by referring in Ulysses to his native land as “the old sow that eats her farrow.”* In Manhattan in 1924 the sale of the manuscript of Ulysses at auction brought $1,975 —about half a cent a word. For years it looked as though the censors of the English-speaking world had determined that Joyce’s book, like himself, should remain in exile.

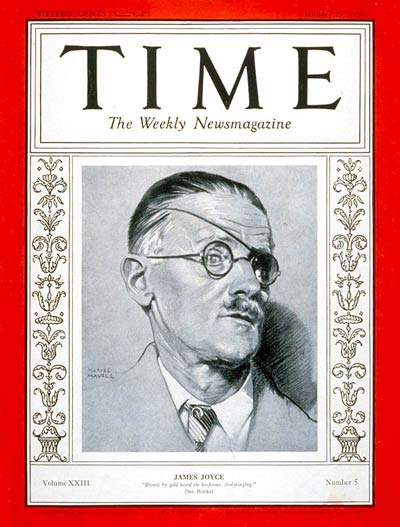

The Author is variously regarded by those who have never read his books as either a dirty-minded old man or a young crackpot. He is neither. Though critics may bark up different trees in assaying his work, most of them agree that Joyce, as an experimentalist with language, is farther out on a limb than any other writer of English.

If readers think Ulysses is difficult, they will throw up their hands in horror over Work in Progress, whose entire “action” takes place in the dreaming mind of a sleeper, whose language is accurately described by one admirer as “intensive, comprehensive, reverberative infixation; the sly, meaty, oneiric logorrhoea, polymathic, polyperverse.” Even friendly critics admit that no plain reader will ever tackle such a book as Work in Progress.

Born 52 years ago in Dublin, James Joyce was educated by Jesuits at Clongowes Wood College, Belvedere College, Royal University. In his early 20’s he left Ireland and the Church for good, took himself and his sleek blonde Galway wife, Nora Barnacle, to Italy. In Trieste, where they spent ten years, and where Joyce supported his family by teaching languages, his son George and daughter Lucia were born. When the War came Joyce found himself an enemy alien (Trieste was then Austrian), managed to move his family to Switzerland. Friends who have seen the series of letters he later wrote the Swiss Customs, in a finally successful attempt to get some trunks out of their official clutches, say it is a model of practical epistolary art. After the War Joyce moved to Paris, where he still lives, a shy. proud private citizen with a worldwide reputation. His few intimate friends include Padraic Colum, James Stephens, Lord and Lady Astor, John McCormack, Sylvia Beach. He rarely misses a chance to hear opera. Himself no mean tenor, he often sings at his mildly convivial parties, at which he urges red wine on his guests, drinks only white himself. Joyce-addicts may now purchase a phonograph record of his voice. Like his predecessor “Homer”‘ who was reputed to be blind. Joyce has long had trouble with his eyes, with periods of virtual blindness. After more than ten operations he can see just well enough to read newspaper headlines, to scrawl his own writing hugely on vast strips of paper. Behind his thick glasses he often wears a black patch over his left eye.

He has proved his hatred of publicity by never granting an interview. Some three years ago he made newshawks wild by remarrying his wife at the London Registry office without offering explanations. His attorney’s guarded comment: “For testamentary reasons it was thought well that the parties should be married according to English law.” Some months later Joyce became a grandfather when his son’s first son (Stephen James) was born.

Enthusiasts have hailed James Joyce as an invigorator and inventor of language. But perhaps he will be longest remembered as the man who made “unprintable” archaic.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com