“Things are really bad between OJ and I, and he’s going to kill me, and he’s going to get away with it.” That’s what Kardashian clan mom Kris Jenner says her friend Nicole Brown Simpson said, just weeks before she was murdered. “She knew exactly what was going to happen to her,” Jenner told Dateline NBC in a special report on the murders that aired Wednesday night.

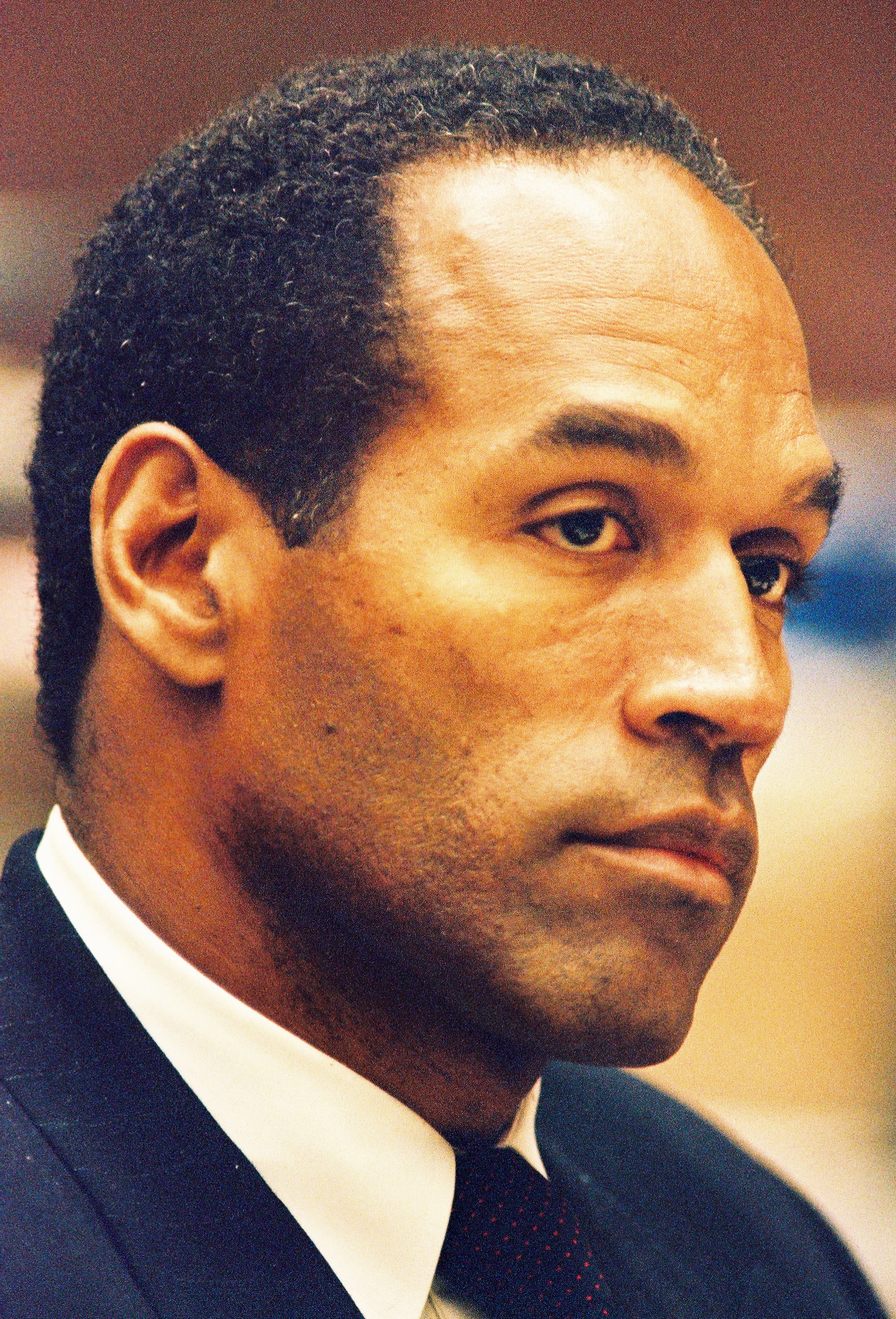

Twenty years ago today, Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman were stabbed to death outside Simpson’s Los Angeles home. And even though OJ Simpson was eventually acquitted of their deaths a year later, the case was a watershed moment for how we think about domestic violence and murder.

“At that point in time, we were still struggling to get people to understand what domestic violence was,” said Rita Smith, who has been the Executive Director of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence since just before the 1994 murders. “And now that term, domestic violence, is something that most people understand. It’s not something that was universally known prior to those murders.”

The fact that Nicole and OJ’s relationship had been abusive before her death was a wakeup call for women across the country. Domestic violence organizations saw an uptick in awareness and reporting “as women from all walks of life realized they were in danger,” said Rona Solomon, deputy director of the Center Against Domestic Violence.

Smith said that the growing awareness about the pervasive danger of domestic violence was instrumental to getting the Violence Against Women Act passed through Congress in 1994. “It really did spur a quicker passage of that law,” Smith said. “And that bill was the largest amount of funding directed towards this issue from the federal government. It was an enormous amount of money.” That bill granted $1.6 billion of funding over six years, and included provisions for mandatory arrests of abusers.

Even though Simpson was eventually acquitted of her murder in criminal court, a civil jury found him responsible for the murders in 1997 and ordered him to pay the victims’ families $33.5 million. Many people saw the civil trial as proof that OJ had killed Nicole, despite the earlier acquittal.

OJ’s history of battering Nicole became a eureka moment in the national understanding of domestic abuse. Nicole had called the police on OJ several times, most notably on New Years 1989, when she appeared with bruises and a cut lip and told officers she feared for her life. But before the OJ case, Smith says, few people made the connection between domestic abuse and homicide.

“There were some juror comments after the verdict that said ‘why were they talking about domestic violence when this is a murder trial?’” Smith said. “When I realized the jurors didn’t understand the connection between domestic violence and homicide and didn’t know why domestic violence was being described to them, I realized that we were not doing a good enough job to get people to understand that this is a pretty common outcome.”

Since then, domestic violence organizations have made a point of emphasizing that battery can lead to murder. According to a 2013 World Health Organization report on global violence against women, 38% of women who are murdered are killed by their partners, and 42% of women who were abused by their partners experience serious injuries.

In 1996, partly as a result of the increased awareness, Congress passed a law that prevented domestic batterers from purchasing guns. And between 1993 and 2007, intimate partner homicide rates decreased 35% for American women, according to a Justice Department study.

“Last time I checked, there were at least 250,000 gun purchases denied because of active restraining orders,” Smith said. “One of the only positives that have come out of Nicole and Ron’s deaths that there have been some significant changes and significant policy changes that have protected other people.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com